Circular reporting, strategy and performance in agri-food companies: a natural resource-based theoretical approach

ABSTRACT

Awareness about the circular economy as a sustainability paradigm is growing globally, being the agri-food sector one of the most significant industries moving towards circular operations. The natural resource-based view theory can provide a basis to analyze organizational resources and capabilities allowing a clear definition of circular economy strategies and performance. How accounting and reporting can leverage these concepts, is being debated currently at the academic level. In this context, this study examines to what extent Argentinian agri-food organizations use circular reporting to translate circular economy strategy into better performance. Survey data were collected from 238 agri-food Argentinian organizations and analyzed using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). General results show that a natural resource-based circular economy strategy positively affects performance and circular reporting has a significant indirect effect on environmental and economic performance, through the improvement of natural resource-based circular economy strategies.

Keywords: Agri-food; Circular economy; Circular reporting; Circular performance; Emerging economies; Argentina.

JEL classification: Q56; M41; M14.

Reporting, estrategia y desempeño de economía circular en empresas agroalimentarias: análisis desde el enfoque teórico basado en recursos naturales

RESUMEN

Es creciente el interés por la Economía Circular (EC) como paradigma para alcanzar la sostenibilidad. El sector agroalimentario, por sus características y trascendencia, está avanzando hacia un modelo de negocio circular. La teoría basada en recursos naturales puede proveer una base teórica para explicar por qué las organizaciones adoptan la EC en sus estrategias de negocio.

Este estudio examina en qué medida organizaciones pertenecientes al sector agroalimentario utilizan información circular para traducir su estrategia de EC en un mejor desempeño ambiental y económico. Para ello, se aplicó un cuestionario a 238 organizaciones argentinas, procesando los datos con ecuaciones estructurales.

Los resultados muestran que la fijación de una estrategia de EC, en base a la teoría de recursos naturales, afecta positivamente el desempeño económico y ambiental. Además, la información contable circular tiene un efecto indirecto significativo sobre el desempeño, mejorando las estrategias de economía circular con un enfoque basado en recursos naturales.

Palabras clave: Agroalimentaria; Economía Circular; Información Circular; Performance Circular; Economías Emergentes; Argentina.

Códigos JEL: Q56; M41; M14.

1. Introduction

The agri-food sector is one of the main industries in the Argentinian economy, as well as for other emerging economies. This sector is facing significant challenges related to their negative environmental impact (Esposito et al., 2020), food loss and waste (Salimi, 2021), implicating the need for a radical redesign of current linear production systems, in a more efficient but also sustainable approach (Jurgilevich et al., 2016). Circular Economy (CE) has risen as a possible solution by optimizing and retaining value and resources (Moraga et al., 2019), creating closed loop systems (Ghisellini et al., 2016).

Over the past decade, CE has gained attention in research (Geissdoerfer et al., 2017), with several authors inquiring about the implications in the agri-food sector (Muscio & Sisto, 2020; Poponi et al., 2022) and results in terms of performance (Mocanu et al., 2022; Sarja et al., 2021). Monitoring progress on CE related activities (Rodríguez-González et al., 2022) constitute a key factor for its successful implementation. Previous studies show that circularity is not necessarily equivalent to environmental sustainability (Blum et al., 2020, Panchal et al., 2021), therefore assessing CE actual impacts on environmental and economic performances (CE targeted performance - CETP) (Solvida & Latan, 2017; Zhu et al., 2010; Botezat et al., 2018), requires further study.

The Accounting field could contribute into the adoption of CE at company level (Scarpellini et al., 2019) via Circular reporting (CR), i.e., CE information/disclosure as a practice of sustainability accounting (Aranda-Usón et al., 2022) assisting the organization in managing, measuring and improving CE application (Llena-Macarulla et al., 2023). Currently, this role of accounting is gaining attention in the academic studies (Larrinaga & Garcia-Torea, 2021). To date, some important questions in academy research relate to how CE is being disclosed on sustainability reporting (SR) (Tiscini et al., 2022), what information and data is needed for circular decision making (Ibáñez-Forés et al., 2022), how CE should be measured and disclosed (Opferkuch et al., 2021) and what indexes or frameworks should be used (Walzberg et al., 2021). Nonetheless, more work is needed to integrate CE within existing accounting tools (Di Vaio et al., 2023).

The natural resource-based view approach (NRBV) (Hart, 1995; Hart & Dowell, 2011) offers a connection between the natural environment and the resources and capabilities of an organization, by focusing on identifying strategic resources that are sources of both competitiveness and environmental sustainability (De Stefano et al., 2016). Thus, CE activities and strategies could become relevant for the company to achieve a competitive advantage by providing value for customers and resources efficiency for the company (Prieto-Sandoval et al., 2019; Rodríguez-González et al., 2022).

A growing number of academic studies have explicitly analyzed CE activities and strategies through the NRBV theory in emerging economies (Sehnem et al., 2022; Mishra et al., 2021) including the effects on performance (Michalisin & Stinchfield, 2010). Using a sample of 460 Mexican automotive companies, Rodríguez-González et al. (2022) analyze the effects of the implementation of CE strategies and sustainable supply chain practices on financial performance, finding a positive relationship. In spite of these, the relationship between CE strategies, CR, and CETP has not been fully examined yet, especially for Latin American countries (Betancourt Morales & Zartha Sossa, 2020), reflecting an empirical gap that requires further exploration.

Thus, taking the NRBV as a conceptual framework of reference, the main objective of this article is to evaluate the influence of CR in the achievement of a more advanced CE strategy, analyzing whether this translates into a better CETP for the case of Argentinian agri-food companies.

By addressing these relationships, the article makes some contributions to the literature on CE, environmental accounting and reporting, and strategic management. Firstly, it provides guidance for the practical application of the NRBV theory in the agri-food industry, focusing on CE strategies and their effects on CETP. Secondly, it explores the role of the CR in this context, enriching the analysis regarding the contributions of sustainability accounting in the implementation of CE in agri-businesses, responding to recent calls to expand accounting horizons (Larrinaga & Garcia-Torea, 2021). Finally, this study provides insights into the agri-food sector of an emerging economy, Argentina, to gain a better understanding of how CE principles can thrive. The importance of Argentina's agri-food industry, both nationally and globally, cannot be overstated. As one of the world's leading food producers and exporters, the agricultural sector plays a crucial role in the country's economy and global food security (OECD/FAO, 2020) representing 7.3% of the GDP in 2021 and 13.4% of total employment in 2019 (Rótolo et al., 2022). Within the region, Argentina ranks second after Brazil in terms of agri-food production and export (FAO, 2021). The strength of Argentina's agri-food industry stems from its abundant natural resources, fertile lands, and favorable climate, allowing it to be a key player in the global food supply (FAO, ECLAC & IICA, 2020). By exploring the challenges and opportunities for implementing CE principles in this pivotal sector, this research contributes to the broader discussion on sustainable agri-food systems in emerging economies. This is also significant, considering the majority of studies have focused so far on developed countries/regions (Betancourt Morales & Zartha Sossa, 2020).

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Next section presents the literature review and discusses hypothesis development linking the NRBV approach to CE Strategies, performance and CR. The third section describes the data collection process and how statistical analysis was conducted. The fourth section presents the results of the PLS-SEM approach. Finally, findings and concluding remarks are discussed, along with limitations and future research directions.

2. Literature review and hypothesis development

2.1. CE Strategy and performance: A Natural resource – based view approach

CE aims to close loops in eco-efficient processes cycles using minimal materials and inputs, providing a more sustainable system (Jurgilevich et al., 2016). Academics usually see CE as a tool to operationalize sustainable development (Kirchherr et al., 2018), promoting economic prosperity and preserving environmental quality (Kravchenko et al., 2019), retaining value for both the global natural environment and economy (Walzberg et al., 2021).

The NRBV proposes three strategic capabilities to address natural environmental constraints: pollution prevention, product stewardship and sustainable development (Kusumowardani et al., 2022; Hart, 1995). To achieve CE goals, organizations must strategically analyze their available resources that promote the development of essential innovations and strategies within the CE framework. Being able to evaluate the adequacy of internal resources and capabilities is essential for the development of a successful CE strategy (Scarpellini et al., 2020; Aragón-Correa & Rubio-Lopez, 2007).

Based on Wijethilake et al. (2017), this study investigates CE NRBV Strategy - CES - in terms of environmental and economic strategy; including in its construction, the three strategic capabilities discussed in the NRBV (Hart, 1995). Social strategy was not considered for being the least developed in terms of CE (Scarpellini, 2021; Marco-Fondevilla et al., 2021).

The research also analyzes CE Management Strategy -CEMS- in terms of the traditional concepts of strategic management (Tonelli & Cristoni, 2019).

At company level, a sustainability strategy improves sustainability performance through a more efficient use of resources, reduces waste and waste generation, improves costs, social reputation, and generates new business innovation capabilities (Bhupendra & Sangle, 2015 in Wijethilake et al., 2017). In addition, the literature has identified a positive relation between CE and corporate financial performance (Afum et al., 2022; Kwarteng et al., 2022; Rehman Khan et al., 2021).

However, CE performance need to be carefully monitored and assessed (Kravchenko et al., 2019), as there are studies that question whether CE is, in practice, environmentally friendly by default (Blum et al., 2020; Haupt & Hellweg 2019; Opferkuch, 2021) or if it can bring economic benefit in all the cases in which it is applied (Gonçalves et al., 2022; Liu & Bai, 2014). Therefore, the relationship between CE Strategies and CETP remains controversial, requiring further exploration.

Using the case of the Indonesian wooden furniture industry, Susanty et al. (2020) conclude that CE practices and CETP differ significantly across SMEs, according to the environmental supply chain cooperation practices. Rashid et al. (2013) indicates that the circular business models and practices are needed for sustainable manufacturing, and that this is a key concept for the improvement of environmental and economic performances. Lieder & Rashid (2016) found that a strong CE strategy plays a fundamental role in performance of manufacturing companies, given According to Katz‐Gerro & López Sintas (2019), interdependence among CE activities should produce better CETP. Following these results, we put forward our first hypothesis:

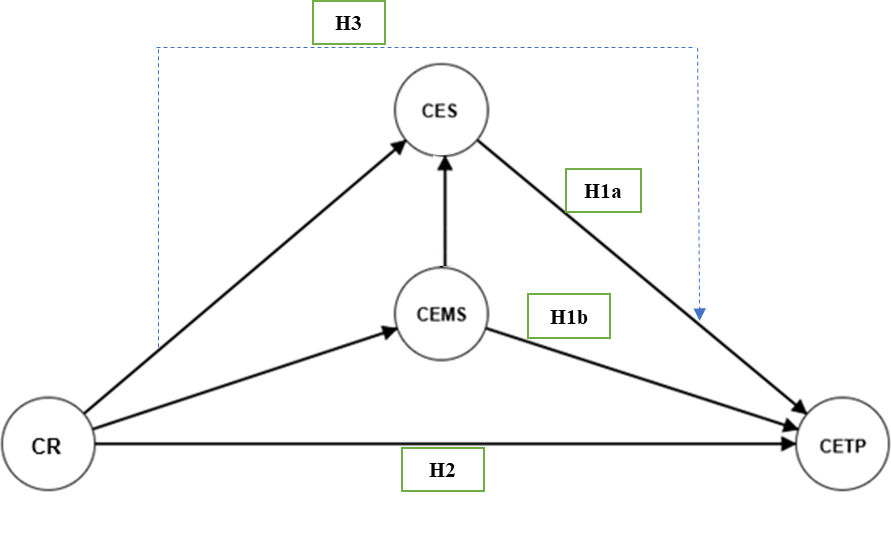

Hypothesis 1a: CES is positively related to the CETP.

Hypothesis 1b: CEMS is positively related to the CETP.

2.2. Circular reporting, CE Strategy and CE performance

CE has the potential to overcome the challenges of sustainable development by improving resource productivity (Khan et al., 2020). However, prior studies show there is a gap between CE theory and practice at company level (Barreiro-Gen & Lozano, 2020), which becomes evident in emerging economies (Gunarathne et al., 2021). Sustainability accounting could be a useful tool to address this gap (Aranda-Usón et al., 2022) supporting strategic decision-making to respond to CE challenges by identifying, collecting and analyzing CE-related financial and non-financial reporting (Wijethilake et al., 2017).

Researchers argue that management control systems have an important role in overcoming the complexities associated with the implementation of sustainability strategies, including CE (Crutzen & Herzig, 2013; Epstein & Buhovac, 2014; Passetti et al., 2014). Thus, information becomes a key resource for the evolution of CE, helping understanding and evaluation of how CE contributes to sustainability (Kravchenko et al., 2019). Furthermore, as indicated by Scarpellini et al. (2020) companies could move towards CE by including key environmental performance indicators, both financial and non-financial, in their reporting practices.

The success of any strategy can be achieved only if performance is clearly measured and monitored (Wijethilake et al., 2017). Control systems such as accounting, can support the implementation of the CE strategy by defining goals through pre-established standards and effectively planning the allocation of resources (Aragón-Correa & Rubio-Lopez, 2007). In this sense, Latif et al., (2020), understands that sustainability accounting dealing with information about environmental impact enhances a company's environmental performance (Jasch 2003, Latif et al., 2020). In broad terms, SAR is an essential portion of maintaining sustainability efficiency (Higgins & Coffie, 2016).

Several scholarly articles have examined the relationship between corporate reporting and environmental and economic sustainability performance, finding mixed results (Doan & Sassen, 2020; Clarkson et al., 2008; Clarkson et al., 2011, Omran et al., 2021). Prior literature has also shown mixed results using different theoretical approaches when analyzing the relationship between environmental and economic performance and environmental disclosure (e.g., Al-Tuwaijri et al., 2004; Hassan & Romilly, 2018; Miroshnychenko et al., 2017). Generally speaking, SR capacity to improve the quality and transparency of nonfinancial disclosures and in turn, the sustainability performance of a company, remains heavily debated (Cortesi & Viena, 2019, Opferkuch et al., 2021; de Villiers & Sharma 2020). Omran et al. (2021) found a positive correlation between integrated reporting practices and environmental performance. They concluded that high quality integrated reporting practices are part of the overall environmentally responsible corporate strategy, and the inclusion of broader ecological concerns into integrated reporting initiatives may enhance its effectiveness, helping in alleviating the negative impact of the corporate activity on the ecosystem (Omran et al., 2021). Latif et al., (2020) pointed out that the improvement in environmental and firm performance comes as the ultimate outcome of the adoption and implementation of environmental accounting, principally by the adoption of different approaches and the reduction of costs (Ferreira et al., 2010; Burritt et al., 2002).

Hence, the achievement of the CETP at the company level depends, partially, on the CR and SR practices conducted, since at this level, the implementation of CE principles requires a robust set of information (Botezat et al., 2018). Therefore, based on Gray (2006), by providing an overview of environmental information, programs and strategies, CR can become the source of CETP.

Hypothesis 2: CR is positively related to CETP.

Accounting as an information and control system has a fundamental role in supporting CE strategy as a means to achieve good CE performance (Wijethilake et al., 2017). Barnabè & Nazir (2021) indicate that SR may have the potential to operate as a change mechanism that holistically and completely represents the activities and strategies of a company in a CE-oriented perspective (Stewart & Niero, 2018). Therefore, CR and SR can shape the internal organizational sustainability strategy (Burritt & Schaltegger, 2001) and encourage sustainable initiatives (Brown & Dillard, 2014), including CE. SR could influence the performance of CE by aligning the values and operations of companies with the principles of CE, strengthening the business and CE strategy in line with the generation of value (Henri & Journeault, 2010; Wijethilake et al., 2017). Following Ducker's notion "what gets measured gets managed" (Haupt & Hellweg, 2019), including CR in corporate reports can show the scope of an organization's contribution and commitment to the environment, supporting the formation of the CE strategy, decision-making and in the process improving performance (Kravchenko et al., 2019).Therefore, this paper proposes the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3: There is a positive indirect effect between CR and CETP, through the improvement of the CES.

Figure 1 illustrates the research framework. For the empirical analysis, three models were developed: the full model examines the relationships between CE Strategies (CES and CEMS) and CETP, integrating the two most developed pillars of sustainability for the case of CE -environment and economy- (Scarpellini, 2021) and the role of the CR in the improvement of CETP. The second and third models address these same relationships, but focusing on: 2. CE environmental strategies and environmental performance and 3. CE economic strategies and economic performance.

Figure 1. Conceptual Framework - Theoretical model and hypothesis

Note: CR: Circular reporting; CEMS: Circular economy management strategies; CES: Circular Economy Natural Resource based Strategy; CETP: Circular economy targeted performance.

The diagram shows the relationships of the theoretical model. The ones not indicated as hypotheses refer to predictions that, although are part of the study, will not be the focus of the current analysis.

3. Methodology

3.1. Questionnaire and Data collection

For the purpose of this study, a self-administrated questionnaire was developed following Peterson (1999) suggested steps. Firstly, a systematic literature review was executed to identify the best indicators for each latent variable. Whenever possible, we selected indicators already used in empirical studies. In other cases, conceptual studies were used to build new ones (Khan et al., 2020). We developed a total of 38 items to evaluate the relationships under analysis (Annex 1).

Next, we sent the questionnaire to four CE and CR specialists and tested it with 5 firms, to determine the adequacy of each measurement item and assess the clarity of the questions, confirming suitability and validity (Dillman, 2000).

Argentina's agri-food sector is currently targeting CE (DNAB, 2017), which is relevant to test our hypotheses in these sectors (Khan et al., 2020). Due to the lack of official data, the sample was obtained through a self-constructed database. All business chambers1 related to the agrifood sector were requested for the list of companies affiliated with contact information during February and March 2021. After depuration, the final survey was sent to 2500 Argentinian agri-food companies of different size, regions and activities2, via email to the top management areas. In the cases of bounce emails or after 2 weeks of no reply managers were contacted via LinkedIn, when available. A total of 438 responses were received from April to October 2021, but only 238 were usable. The other questionnaires were unusable because the respondents have left more than 5% questions unanswered. Finally, we obtained a 9,52% response ratio, similar to other studies on the matter (Mura et al., 2020; Sumter et al., 2021). In regards to the suitability of the sample size, the recommended rule of thumb of Hair et al., (2012) was followed: at least 10 times the number of indicators of the construct with the highest number of indicators. Table 1 - Panel A, shows the data collection details.

Table 1 - Panel B shows the characteristics of the 238 respondent organizations. Those profiles are consistent with official statistics and previous studies that analyze the Argentinian agri-food sector structure and importance (Ministerio de Desarrollo Productivo, 2021). 62.61% of survey respondents have an upper managerial position (CEO, General Managers, Owners), and 37,39% are middle managers. 51.26% work in production and sustainability areas, 30.67% management, accounting and finance, and the rest -18.07%- work in other areas such as: Safety, health and environment -SHE- and Quality.

Table 1 – Data collection and sample features

| PANEL A - Data collection details | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Agri Food companies interested in Circular Economy initiatives | ||

| Country | Argentina | ||

| Sample | 238 companies | ||

| Data collection process | Questionnaire sent via Email and LinkedIn | ||

| Date | April to October 2021 | ||

| PANEL B Company features | % | Size | % |

| Agricultural production | 29.41% | Micro | 21.01% |

| Processing of Primary Products Processing | 30.25% | Small | 18.49% |

| Oils and fats | 5.04% | Medium | 20.17% |

| Meat industry | 7.56% | Large | 40.34% |

| Fish industry | 2.52% | ||

| Millers and starches | 8.40% | Employees | % |

| Conservation of fruits and vegetables | 5.04% | 1 a 50 | 34.03% |

| Others | 1.68% | 51 a 249 | 26.05% |

| Processed and ultra-processed | 18.91% | 250 a 999 | 19.33% |

| Seasonings, spices and extracts | 3.78% | 1000 a 4999 | 16.39% |

| Animal feeding | 2.10% | > 5000 | 4.20% |

| Cookies and candies | 3.36% | ||

| Bakery and pasta | 5.88% | Listed Company | % |

| Others | 3.78% | No | 83.61% |

| Beverages | 14.29% | Yes | 16.39% |

| alcoholic beverages | 9.66% | ||

| Non-alcoholic beverages (except milk) | 4.62% | Capital | % |

| Dairy products | 7.14% | Foreign | 22.69% |

| Total | 100.00% | National | 77.31% |

3.2. Measurement of variables

Based on previous research, the study measures the NRBV CE Strategy (CES) as a reflective-reflective second-order hierarchical construct in terms of environmental and economic strategy (Wijethilake et al., 2017; Torugsa et al., 2013; Gallardo-Vázquez & Sanchez-Hernández, 2014). CES consisted of 13 items, 7 for the Economic Strategy and 6 for the Environmental strategy, based on the NRBV and previous literature (Among others: Ellen Macarthur Foundation, 2017; Platform to Accelerate the Circular Economy, 2021; Aranda-Usón et al, 2020; Verbeek, 2016; Gusmerotti et al., 2019; Sehnem et al., 2019).

The latent variable CE Management Strategy (CEMS) was measured as a reflective first-order construct, with 7 items (Baumgartner, 2014; Bettley & Burnley, 2008; Gallardo-Vázquez & Sanchez-Hernández, 2014).

CR variable is evaluated as a first-order construct made up of 7 items, based on previous literature (Bhimani et al., 2016; Thorne et al., 2014; Windolph et al., 2014; Hapsoro & Husain, 2019).

Lastly, CE Targeted Performance (CETP) variable was measured as a reflective-reflective second-order hierarchical construct, composed by the economic and environmental performance constructs. This is an adaptation of what was proposed by Gallardo-Vázquez & Sanchez-Hernández (2014) and Wijethilake et al. (2017) for the variable Sustainability performance. A total of 11 items were used, 6 refer to environmental performance and 5 to economic performance (Susanty et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2010; Botezat et al., 2018).

The majority of the items described were measured using a scale with percentages of 4-level applications (null, low, medium, high). In the case of SR, the scale was also constructed with 4-levels: 1: No SR, 2: SR with no CE; 3: SR with CE included along with environmental reporting, 4: SR with a specific CE chapter.

Table 2 provides the measurement items within each construct, the factor loadings, and descriptive statistics for each construct.

Table 2. First and second order constructs features

| Items and constructs | Factor Loading | Cronbach | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CE management strategy – (CEMS) | 0.921 | 0.939 | 0.690 | |

| The firm has a CE management office | 0.699 | |||

| A CE general strategy has been developed | 0.915 | |||

| Managers and chiefs have a strong commitment with circular economy in the company | 0.860 | |||

| There is an action plan with specific goals for the circular management of the business | 0.892 | |||

| CE is part of the company's objectives | 0.908 | |||

| Staff are trained on CE strategy | 0.855 | |||

| Environmental auditing programs, e.g., ISO 14000 | 0.640 | |||

| CE Nature resource-based Strategy (CES) | ||||

| CE Nature resource-based Strategy – Environment (CES-ENV) | B: 0.891 | 0.791 | 0.855 | 0.543 |

| Objectives and a plan have been established for the minimization of waste and emissions | 0.745 | |||

| Inputs used are biodegradable, non-toxic and/or come from pre-used or recycled materials. | 0.797 | |||

| Recovery and reuse of energy and treatment of wastewater | 0.785 | |||

| Packaging keeps products safe, providing more time for consumption | - | |||

| Energy consumed comes from renewable sources | 0.675 | |||

| Work is being done to achieve a balanced exchange of nutrients in operations | 0.674 | |||

| CE Nature resource-based Strategy - Economic (CES-ECO) | B: 0.906 | 0.772 | 0.846 | 0.525 |

| Inevitable production food losses are reworked | 0.687 | |||

| Production techniques and standards minimize the use of inputs | - | |||

| Investments/participation in public and/or private CE initiatives | 0.819 | |||

| Selection criteria for industrial suppliers and buyers based on CE | 0.658 | |||

| By-products are used in new food products or reused for animal feed, fertilizer, biomaterial | 0.740 | |||

| Cooperation with companies to establish circular supply chains and/or industrial symbiosis | 0.711 | |||

| Reverse packaging logistics and/or cooperation for a warehouse system is offered | - | |||

| Circular Reporting (CR) | 0.957 | 0.966 | 0.802 | |

| Internal reports on circular management results | 0.867 | |||

| CE strategies and objectives are communicated to stakeholders | 0.941 | |||

| CE practices and actions are communicated to stakeholders | 0.943 | |||

| EC results and performance are communicated to stakeholders | 0.948 | |||

| Qualitative information is used | 0.926 | |||

| Quantitative information including CE-specific indicators is used | 0.935 | |||

| Sustainability report with CE | 0.675 | |||

| CE targeted performance (CETP) | ||||

| CE targeted performance – Environment (CETP – ENV) | B: 0.957 | 0.883 | 0.911 | 0.633 |

| Food waste reduction | 0.688 | |||

| Reduction of emissions | 0.844 | |||

| Reduction of waste and contamination of water | 0.814 | |||

| Solid waste reduction | 0.773 | |||

| Decrease in the consumption of hazardous / harmful / toxic materials | 0.833 | |||

| Decrease in the frequency of environmental accidents | 0.810 | |||

| CE targeted performance – Economic (CETP – ECO) | B: 0.959 | 0.904 | 0.929 | 0.724 |

| Cost reduction in purchasing materials | 0.834 | |||

| Decrease in the cost of water and energy consumption | 0.852 | |||

| Cost reduction for waste treatment | 0.905 | |||

| Cost reduction in final waste disposal | 0.893 | |||

| Decrease in fines/sanctions for environmental accidents | 0.761 |

Note: Items with low factor loadings (FL) were eliminated and are included in the table with a “-“.

3.3. Statistical analysis

Regarding the treatment and cleaning of the data, answers with less than 5% of missing information were replaced using the mean imputation method (Hair et al., 2017). Extreme points, non-normality, and the common method of variance were analyzed using SPSS. Harman's single factor test was used to determine whether or not common method bias affects the results. The first factor explains 43.28% of the total variance (Podsakoff et al., 2003), indicating no substantial common method bias. Following Hair et al. (2017), the study evaluates the collinearity for the internal model, considering that the PLS SEM analysis consists only of reflective measurements. The variance inflation factors (VAF) were below the acceptable norm of 5, with the highest value being 2.98. Taken together, the results support the absence of significant collinearity.

The study uses SmartPLS 3.0 to analyze the hypotheses through Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Model (PLS-SEM). This method estimates path diagrams with latent variables and indirect measurements, using multiple indicators (Hair et al., 2017).

PLS-SEM was chosen over Covariance-Based Structural Equation Modeling (CB-SEM) because it is less restrictive and has softer data requirements than CB SEM. In addition, PLS-SEM has higher predictive power than CB-SEM (Licerán-Gutiérrez & Cano-Rodríguez, 2019). PLS-SEM consists in the analysis of two models: 1. The measurement model, which examines the relationship between latent variables and measured items, and 2. The structural model, which analyzes the relationships between latent variables (Chin, 2010). Two stage differentiated approach technique was used in the analysis of the first and second order constructs (Sarstedt et al., 2019).

4. Results and discussion

Firstly, to analyze construct reliability and convergent validity, items with factorial loadings less than 0.6 were eliminated (Table 2). Remaining items were all significant at p>0.01. In order to improve the construct's reliability of the CES-ECO latent variable the item with the lowest FL was eliminated. After these procedures, Cronbach's alpha, composite reliability (CR), and average variance explained (AVE) exceeded the acceptable limits of 0.7, 0.7, and 0.5, respectively, in all constructs (Hair et al., 2017).

To assess discriminant validity, Fornell-Larcker criteria and HTMT were used (Table 3). In these cases, the correlations between constructs did not exceed the square root of the AVE, with the exception of Environmental and Economic Performance (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). According to Hair et al. (2017), this exception is acceptable since these two first-order constructs belong to the same second-order construct: CETP. In the case of the HTMT correlations, the maximum suggested value of 0.9 is not exceeded in any case, except for the same relation mentioned before: CETP-ENV and CETP-ECO. Cross-load analysis reveals that all items load on their respective constructs. In conclusion, these indicators support acceptability of the properties of the measurement model in terms of reliability, convergent and discriminant validity (Chin, 1998).

Table 3. Discriminant validity for first order constructs

| PANEL A - Fornell – Larcker | PANEL B - HTMT | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CETP-ECO | CETP-ENV | CES-ENV | CES-ECO | CEMS | CR | CETP-ECO | CETP-ENV | CES-ENV | CES-ECO | CEMS | |

| CETP-ECO | 0.851 | ||||||||||

| CETP-ENV | 0.836 | 0.795 | 0.937 | ||||||||

| CES-ENV | 0.561 | 0.585 | 0.737 | 0.652 | 0.677 | ||||||

| CES-ECO | 0.552 | 0.521 | 0.616 | 0.725 | 0.658 | 0.629 | 0.790 | ||||

| CEMS | 0.503 | 0.483 | 0.556 | 0.681 | 0.830 | 0.547 | 0.526 | 0.631 | 0.801 | ||

| CR | 0.499 | 0.464 | 0.538 | 0.617 | 0.769 | 0.895 | 0.531 | 0.496 | 0.599 | 0.717 | 0.821 |

Note: Panel A shows the intercorrelations of the first-order latent variables and the square root of the AVE.

Panel B presents the hetero-trait mono-trait correlation matrix.

Table 2 contains the details of the abbreviations used for the variables.

4.1. Structural model

Table 3 shows the analysis of the first and second order constructs. In all cases the acceptance criteria are exceeded: Cronbach's Alpha, CR and (AVE). Betas values (p>0.01) are also presented and R2 of first order constructs are greater than 0.44 indicating moderate levels of adjustment, which are strong enough to support the model design (Chin, 1998; Hair et al., 2017).

The structural model is analyzed in two stages. Firstly, path coefficients are evaluated (Table 4). Then, the indirect effects are analyzed through mediating variables (Table 5).

Table 4 shows the parameters estimated using Bootstraping PLS-SEM with 5000 subsamples and the evaluations of the structural coefficients for the three measurement models (1) Full Model (2) CE Environmental model and (3) CE Economic model. The results show that all main coefficients are positive and significant under the three models with p<0.01 and p<0.05.

The relevance of the significant relationships and the predictive capacities of the measurements were also evaluated to determine the goodness of fit in PLS (Chin, 1998). As shown in Table 4, the R2 values of the second order constructs range from 35.60% to 61.50%. The predictive relevance values (Q2) generated through blindfolding procedure oscillate between 0.202 and 0.450, above zero, and therefore confirm the predictive relevance of the three proposed models. Both the CES as well as the CES-ECO and CES-ENV have average effects (f2) on the CETP (0.238), CETP-ECO (0.101) and CETP-ENV (0.209) respectively. All the other exogenous constructions reveal small effects on the endogenous variables, particularly the case of CR which has low direct effects on performance in all proposed models.

Table 4. Structural model analysis

| Full model | R2 | Q2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEMS | 0.592 | 0.588 | |||

| CES | 0.508 | 0.412 | |||

| CETP | 0.428 | 0.247 | |||

| Relation coefficients | Path | f2 | |||

| CEMS➔CES | 0.477*** | ||||

| CEMS➔CETP | 0.063 | 0.002 | |||

| CES➔CETP | 0.525*** | 0.238 | |||

| CR➔CEMS | 0.769*** | ||||

| CR➔CES | 0.277*** | ||||

| CR➔CETP | 0.115* | 0.009 | |||

| Environmental Model | R2 | Q2 | Economic Model | R2 | Q2 |

| CEMS | 0.592 | 0.588 | CEMS | 0.592 | 0.587 |

| CES-ENV | 0.343 | 0.287 | CES-ECO | 0.487 | 0.375 |

| CETP-ENV | 0.384 | 0.209 | CETP-ECO | 0.350 | 0.242 |

| Relation coefficients | Path | f2 | Relation coefficients | Path | f2 |

| CEMS➔CES-ENV | 0.351*** | CEMS➔CES-ECO | 0.507*** | ||

| CEMS➔CETP-ENV | 0.153** | 0.014 | CEMS➔CETP-ECO | 0.113 | 0.007 |

| CES-ENV➔CETP- ENV | 0.443*** | 0.209 | CES-ECO➔CETP-ECO | 0.357*** | 0.101 |

| CR➔CEMS | 0.770*** | CR➔CEMS | 0.769*** | ||

| CR➔CES-ENV | 0.271*** | CR➔CES-ECO | 0.229*** | ||

| CR➔CETP-ENV | 0.107 | 0.007 | CR➔CETP-ECO | 0.190*** | 0.022 |

Notes: *p<0,10; **p<0,05; ***p<0,01 (two tailed).

Effect size (f2): 0,02= small; 0,15= medium; 0,35=large (Chin, 2010).

In Table 2 abbreviations of the variables can be found.

Table 5 shows the results of the indirect effects analysis of CR on CETP through the mediation of the CES. To reveal the magnitude of the mediation impact, the direct and indirect effects were assessed following Hair et al. (2017). When the indirect effect is not significant there is no mediation. On the contrary, if the indirect effect is statically significant, mediation exists and this can be full mediation or partial mediation depending on the direct effect being not significant or significant respectively (Hair et al., 2017).

Table 5. Indirect effects of circular reporting over Performance. Mediating effects of Strategy variables

| Full Model | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total effects | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR➔CES➔CETP | 0.115* | 0.145*** | 0.502*** | Partial mediation |

| Environmental Model | ||||

| CR➔CES-ENV➔CETP-ENV | 0.107 | 0.120*** | 0.465*** | Full mediation |

| Economic Model | ||||

| CR➔CES-ECO➔CETP-ECO | 0.190*** | 0.082*** | 0.499*** | Partial mediation |

Notes: *p<0.10, **p < 0.05, ***, p < 0.01

The analysis shows that CES acts as a mediator variable in the models studied. In the case of the full model, partial mediation is confirmed with both direct and indirect effects being statistically significant.

On the Environmental model the effect is full mediation since there is no significant direct effect. Lastly, for the Economic model, CES partially mediates the relationship between CR and CETP. This means that CR exerts a positive indirect effect on CETP, through the improvement of CES (H3)

Table 6 shows a summary of the results of the analysis of the hypotheses.

Table 6. Summary of hypothesis

| Full Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path | f2 | Result | ||||

| H1a.: CES➔CETP | 0.525*** | 0.238 | Supported | |||

| H1b: CEMS➔CETP | 0.063 | 0.002 | Rejected | |||

| H2: CR➔CETP | 0.115* | 0.009 | Supported | |||

| H3: CR➔CES➔CETP | Table 5 | Supported | ||||

| Environmental Model | Economic Model | |||||

| Path | f2 | Result | Path | f2 | Result | |

| H1a.: CES➔CETP | 0.443*** | 0.209 | Supported | 0.357*** | 0.101 | Supported |

| H1b: CEMS➔CETP | 0.153** | 0.014 | Supported | 0.113 | 0.007 | Rejected |

| H2: CR➔CETP | 0.107 | 0.007 | Rejected | 0.190*** | 0.0022 | Supported |

| H3: CR➔CES➔CETP | Table 5 | Supported | Table 5 | Supported | ||

Note: In the case of H3, we refer to Table 5 for the detail of the value of the beta coefficients, direct, indirect and total effects. Table 2 contains the details of the abbreviations used for the variables.

4.2. Discussion

Results show that, in the context of the sampled agri-food companies in Argentina, CR positively and significantly affects CE implementation and improves CETP on both environmental and economic perspective, through the improvement in the design and application of the organization's CES. This takes place directly in the cases of the Full and Economic model and indirectly in all three models, via the mediation analysis of CES. Companies providing stakeholders with information related to their CE strategies, activities and performance, have a better understanding of CE implications and, therefore, are able to reduce the aforementioned gap between theory and practice (Barreiro-Gen & Lozano, 2020). This may be due to the transformative capacity of accounting and reporting (Eccles & Serafein, 2015), that contributes to integrating CE principles into the organizational strategies and activities (Gunarathne et al., 2021), leading to a more accurate and specific implementation.

The findings complement previous research that has explored the effects of environmental disclosure on sustainable performance (Clarkson et al., 2008) and the role of CES in improving environmental and economic performance (Aranda-Usón et al., 2020; Sehnem et al., 2019). Other studies in the context of emerging economies have found similar outcomes: Kuo & Chang (2021) found that firms disclosing more CE reporting were associated with significantly higher sustainable growth rate and return on equity.

Regarding CES, a positive and significant relationship with the CETP was found in all the models. NRBV theory highlights the strategic importance of natural resources for firm success. By focusing on the preservation and regeneration of resources through practices such as closed-loop production and waste reduction, CE can enhance the natural resource management capabilities of firms. This shift towards circularity aligns with the NRBV perspective of leveraging unique resources to create and sustain competitive advantages. By adopting CES that enhance natural resource management, firms can develop unique capabilities that support long-term competitiveness and generate better performance -CETP-.

CEMS relationship with CETP is only significant in the environmental model. This can be explained by the traditional link of sustainability actions and in this case of CE with the environmental pillar, having to further emphasize the development of the economic and social pillars. This is consistent with previous studies that analyze the link between control systems and sustainability performance (Wijethilake et al., 2017).

Within the framework NRBV theory, the study shows how the sampled companies can improve their CETP by adopting CES, supporting the idea that CR can have an indirect impact on economic and environmental performance through the improvement of CES. This indicates that the implementation of CE strategies and the adoption of CR can complement each other to achieve better performance in the Argentine agri-food companies surveyed.

5. Conclusions

The main objective of this paper was to empirically assess the role of accounting, via CR, in CE implementation strategies and results -CETP- with the lens of the NRBV theory. This objective was analyzed through the construction of three models, one complete and two in relation to the most developed pillars of sustainability for the CE, environmental and economic.

The findings of this study can lead to valuable implications for organizations and policymakers by illustrating the potential of SAR to improve CE and CETP in the context of the Argentine agri-food companies surveyed. This may serve as a specific reference for agri-food companies to implement and continuously improve their SR and CE measurement systems, focusing on their reporting strategy by satisfying information needs that arise due to the developments of the sustainability front (Gunarathne et al., 2021). In the studied context, companies that manage to incorporate CR into their CES and CEMS are likely to achieve better environmental and economic performance, thus contributing to the overall sustainability of the agri-food sector (Aranda-Usón et al., 2020; Gusmerotti et al., 2019).

Secondly, the study highlights the mediating role of CES in translating circular reporting efforts into improved performance outcomes in the surveyed Argentine agri-food companies, which has important implications for the design and implementation of circular economy management strategies and practices. As there is a clear link between NRBV and CE, when seeking to improve CE performance organizations should make an accurate analysis of their natural resources and capabilities allowing them to exploit the comparative advantage CE can generate.

For policymakers in Argentina, the findings emphasize the need to provide incentives and support in the area of SR accounting and reporting, improving legal and professional frameworks to capitalize the positive effects of CR on CE activities. This could also play a crucial role in the adoption of CE practices and principles by promoting the integration of CEMS and CES into CR. Moreover, results could help in the improvement of the environmental and economic performance of Argentine agri-food companies, contributing to the overall sustainability of the sector in the country and setting a business case for CE.

This paper has some limitations and provides opportunities for future research. Firstly, is limited to the sampled firms and results should not be generalized. Despite all the procedures followed, the sample is not statistically representative, being not possible to determine this situation through confidence intervals of representative variables of the population. Future research could address this limitation by using larger samples taking into account different sectors, increasing the power and generalizability of the empirical findings (Omran et al., 2021), Secondly, this is a cross-sectional study and no trends can be analyzed. A longitudinal study would allow evolutionary patterns and drivers of CE in the sector. Thirdly, this document does not analyze the social pillar, which is still under development, but undoubtedly has significant importance in the development of CE. Finally, future studies can focus on qualitative research, complementing the results analyzing how CR leads to CE improvement and which are the most appropriate tools to do so.

Annex 1

Annex 1. Content validity of the variables and items developed

| Construct | Items | Authors |

|---|---|---|

| CE management strategy – CEMS | 7 | |

| CE management office | Bhimani et al. (2016); Thorne et al. (2014); Windolph et al. (2014); Hapsoro & Husain (2019); Verbeek (2016). | |

| A CE general strategy has been developed | ||

| Managers and chiefs have a strong commitment with circular economy in the company | ||

| There is an action plan with specific goals for the circular management of the business | ||

| CE is part of the company`s objectives | ||

| Staff are trained on the CE strategy of the company | ||

| Environmental auditing programs, e.g., ISO 14000 | ||

| CE Nature resource-based strategy - CES | 13 | Ellen Macarthur Foundation (2017); Laboratorio de Ecoinnovación (2017); ONU FAO (2020); Platform for Accelerating the Circular Economy (2021); Stewart & Niero (2018); Aranda-Usón et al. (2020); Verbeek (2016). |

| CE Nature resource-based Strategy – Environment – CES - ENV | 6 | |

| Objectives and planification have been set for the minimization of waste and emissions | Borrelli (2018); Burggraaf et al. (2020); Cullen & De Angelis (2021); Dangelico et al. (2019); Dora et al. (2021); Dudin et al. (2016); Fortunati et al. (2020); Farooque et al. (2019); Fassio & Tecco (2019); Giudice et al. (2020); Nowicki et al. (2020); Kleine Jäger & Piscicelli (2021); Misso & Varlese (2018); Niero et al. (2017); Pauer et al. (2019); Pimbert (2015); Sehnem et al. (2020); Stewart & Niero (2018); Ventura et al. (2018); Viola et al. (2013); Zucchella & Previtalli (2019). | |

| Inputs used are biodegradable, non-toxic and/or come from pre-used or recycled materials. | ||

| Recovery and reuse of energy and treatment of wastewater | ||

| Packaging keeps products safe, providing more time for consumption | ||

| Energy consumed comes from renewable sources | ||

| Work is being done to achieve a balanced exchange of nutrients in operations | ||

| CE Nature resource-based Strategy - Economic - CES - ECO | 7 | |

| Inevitable production food losses are reworked | Batista et al. (2019); Bellia & Pilato (2014); Borrelli (2018); Burggraaf et al. (2020); Cullen & De Angelis (2021); Dangelico et al. (2019); Dora (2020); Dora et al. (2021); Donner et al. (2020); Dudin et al. (2016); Farooque et al. (2019); Fassio & Tecco (2019); Fortunati, et al. (2020); Giudice et al. (2020); Kleine Jäger & Piscicelli (2021); Laso et al. (2018); Misso & Varlese (2018); Piscicelli (2021); Principato et al. (2019); Pimbert (2015); Nasution et al. (2020); Nowicki et al. (2020); Sehnem et al. (2020); Stewardt & Niero (2018); Viola et al. (2013); von Braun (2018); Vlajic et al. (2018); Zucchella & Previtalli (2019). | |

| Production techniques and standards minimize the use of inputs | ||

| Investments/participation in public and/or private CE initiatives | ||

| Selection criteria for industrial suppliers and buyers based on the CE | ||

| By-products are used in new food products or reused for animal feed, fertilizer, energy | ||

| Cooperation with companies to establish circular supply chains and/or industrial symbiosis | ||

| Reverse packaging logistics and/or cooperation for a warehouse system is offered | ||

| Circular Reporting – CR | 7 | |

| Internal reports on circular management results | Bhimani et al. (2016); Thorne et al. (2014); Windolph et al. (2014); Hapsoro & Husain (2019). | |

| CE strategies and objectives are communicated to stakeholders | ||

| CE practices and actions are communicated to stakeholders | ||

| CE results and performance are communicated to stakeholders | ||

| Qualitative information is used | ||

| Quantitative information including CE-specific indicators is used | ||

| Sustainability report with CE | ||

| CE targeted performance - CETP | 11 | |

| CE targeted performance – Environment – CETP - ENV | 6 | |

| Food waste reduction | Susanty et al. (2020); Zhu et al. (2010); Botezat et al. (2018). | |

| Reduction of emissions | ||

| Reduction of waste and contamination of water | ||

| Solid waste reduction | ||

| Decrease in the consumption of hazardous / harmful / toxic materials | ||

| Decrease in the frequency of environmental accidents | ||

| CE targeted performance – Economic – CETP - ECO | 5 | |

| Cost reduction in purchasing materials | Susanty et al. (2020); Zhu et al. (2010); Botezat et al. (2018). | |

| Decrease in the cost of water and energy consumption | ||

| Cost reduction for waste treatment | ||

| Cost reduction in final waste disposal | ||

| Decrease in fines/sanctions for environmental accidents |