What do personal metaphors tell us about accounting and auditing professionals?

ABSTRACT

This study examines the personal metaphors used by students enrolled in the last year of their Business Administration degree regarding their future role as accountants and auditors. The drawings and explanation of the personal metaphors were obtained from an open questionnaire, and they are categorized using the stereotype classification by Richardson et al. (2015). The metaphors are categorized into traditional and contemporary depending on the students’ view of the activities done by the professionals and into positive and negative depending on the personal traits they attributed to them. First, we identified the distribution of stereotypes for the role of accountant and second, for auditor. We also analyzed the participants' beliefs about the dominance of their metaphors in the profession and in society. Third, we examined the differences between the two roles. Subsequently, the study focuses on the changes that in-class interventions produce in students’ perceptions of their role as future accountants and auditors. Finally, this study investigates students’ profiles and characteristics such as gender, age, job preference and internship. The findings reveal that most participants have traditional perceptions of accounting and auditing professionals.

However, evidence also suggests that students use more traditional metaphors for the accountants than for auditors. There are also more metaphors with positive connotations in the auditing profession than in accounting. In some cases, in-class intervention is effective shifting students’ perceptions about accountants and auditors toward more contemporary and positive ones. By combining the metaphors theory and accounting stereotype framework, this study provides a unique approach to understanding future professionals' perceptions of accountants and auditors. Given the social function of the accounting and auditing professions and the concerns about the shortage of accountants and auditors, it is important to study this question which helps revert certain negative images and increase the number of potential candidates.

Keywords: Accountants; Auditors; Personal metaphors; Stereotypes; Undergraduate accounting students.

JEL classification: M41; M42.

¿Qué expresan las metáforas personales sobre los profesionales de la contabilidad y la auditoría?

RESUMEN

Nuestro estudio se centra en el análisis de las metáforas personales de los estudiantes de último año del Grado de Administración y Dirección de Empresas sobre su futuro rol como profesionales de la contabilidad y la auditoría. A través de un cuestionario abierto, obtenemos los dibujos y la explicación de las metáforas personales que posteriormente categorizamos utilizando la clasificación de estereotipos realizada por Richardson et al. (2015). Las metáforas sobre los futuros profesionales se categorizan en tradicionales y contemporáneas, dependiendo de la visión de los estudiantes sobre el trabajo a realizar por el experto; y en positivas y negativas en función de los rasgos personales que se le atribuyan. Primero, identificamos la distribución de estereotipos para el rol del profesional contable y segundo, para el rol del auditor. Asimismo, analizamos la creencia que tienen los participantes sobre la dominancia de sus metáforas en la profesión y en la sociedad. Tercero, examinamos las diferencias entre ambos roles. Posteriormente, estudiamos los cambios que se producen tras la realización de una intervención en clase. Por último, investigamos la relación que tienen las características de los participantes con la elección de la metáfora. Los resultados muestran que la mayoría de los participantes mantienen una visión tradicional tanto del rol de contable como del rol de auditor. No obstante, los estudiantes utilizan más metáforas tradicionales para los profesionales contables que para los auditores. Tras la intervención se observan ciertos cambios en las percepciones de los estudiantes hacia metáforas más contemporáneas y positivas. Este estudio proporciona un enfoque único para comprender las percepciones de los futuros profesionales sobre los contables y los auditores debido la combinación de la teoría de la metáfora y el marco conceptual de la formación de estereotipos en contabilidad. También aporta una reflexión sobre las intervenciones que se pueden implementar para mejorar la imagen de la profesión en el imaginario social y así aumentar el número de candidatos cualificados, ante la preocupación por la disminución de la demanda de profesionales en contabilidad y auditoría.

Palabras clave: Profesional contable; Auditores; Metáforas personales; Estereotipos; Estudiantes universitarios de contabilidad.

Códigos JEL: M41; M42.

1. Introduction

The role of the accounting and auditing profession has evolved continuously and gained increasing importance in society. The business landscape is undergoing a transformation due to a variety of factors such as digital technologies and artificial intelligence development and worries about sustainability and climate change. There has been a call for research that considers the importance of accounting as a multidimensional technical, social, and moral practice (Carnegie et al., 2023). In this context, accounting preconceptions are a matter of concern not only for the profession but also for society. According to the Association of International Certified Professional Accountants (2021), the Unites States of America is currently facing a shortage of accountants due to a combination of factors (a decrease in students who have completed a bachelor’s degree in accounting, a steady decline in new CPA candidates, a large number of CPAs retiring and an exodus of accountants and auditors to other professions), which may be a risk for businesses and the economy. Other countries in Europe such as the United Kingdom (ICAEW, 2023) and Spain (Cinco días, 2023) are in similar situations. The image of the profession was also damaged by the Enron, Worldcom, and Lehman Brothers accounting scandals of the 21st century (Carnegie and Napier, 2010). Given the above concerns and the social function of the accounting and auditing professions, there are calls in academia and business to investigate this question from a theoretical and practical angle. Only with a more complete picture will it be possible to continue fulfilling the relevant function that the accountants and auditors play in the economy, helping to revert certain negative images and increasing the number of potential candidates.

Students’ stereotypes are influenced by the social and cultural representations of the accounting profession (Caglio et al., 2019). Stereotypes, once formed in the minds of individuals, tend to persist (Hinton, 2000; Leão and Gomes, 2022). Social media has mainly shown a traditionally pejorative image of accountants and auditors (Carnegie and Napier, 2010; Smith and Jacobs, 2011). As a result, existing studies have revealed that many students have a preconception of the accounting profession as boring, numerical, predictable, and rule based. They also believe that a professional matches the traditional stereotype, which is conservative, methodical, and individualistic (Byrne and Willis, 2005; Caglio et al., 2019; Mellado et al., 2020). Anecdotal evidence suggests that not only occupations such as accounting, taxation, and data analysis have a boring connotation in society, but professionals in these occupations also seem to be perceived as boring (Van Tilburg et al., 2022). One undesirable consequence is that a traditional accountant’s vision and negative images may discourage students from enrolling in the profession (Durocher et al., 2016; Karlsson and Noela, 2022). In fact, excellent students with adequate skills and capabilities in the accounting and auditing profession may choose an alternative career because of their preconceptions.

Nevertheless, the literature has documented a cultural effort toward a more optimistic image of the accounting profession (Baldvinsdottir et al., 2009; Jeacle, 2008; Richardson et al., 2015). Moreover, Durocher et al. (2016) revealed a special effort of accounting firms to change the traditional perception of the professional from the “bean counter” stereotype to a better image. Several studies have revealed that accountants are traditionally associated with high levels of trust, morality, ethics, reliability, competence, and high levels of responsibility (Caglio et al., 2019; Carnegie and Napier, 2010, Leão and Gomes, 2022). Beyond the positive traditional view, the picture of a contemporary business professional with managerial and social skills who plays an important role in society is extending, indicating progress in the social image of accountants and auditors (Jelinek and Boyle, 2022; Richardson et al., 2015). In this context, some students are changing their negative perceptions of accounting and auditing professionals into a positive image, to professionals that require high levels of competence and moral values (Espinosa-Pike et al., 2021). Since students can also be inspired by relatives and teachers who share their perspectives about the profession (Caglio et al., 2019; Karlsson and Noela, 2022), class time is an opportunity for accounting professors to help students develop an image closer to the reality of the profession. Prior literature suggests that interventions to connect students to the profession may improve students’ ideas about professionals of those careers (Espinosa-Pike et al., 2021; Navallas et al., 2017).

Existing research has used different methods to identify and interpret accounting stereotypes. The most common methods are surveys, interviews, and images published in different media, such as movies, books, and comics (Byrne and Willis, 2005; Caglio et al., 2019; Richardson et al., 2015). However, to date, there has been little research that has investigated, interpreted, and understood accountant and auditor stereotypes through the visual image created by students. Furthermore, very few studies have focused on metaphor theory to capture the mental processes by which accounting stereotypes and perceptions are conceived. Some exceptions are the studies published by Mellado et al. (2017) (which qualitatively explored MBA students’ personal metaphors about their future role as directors) and Mellado et al. (2020) (which compares participants’ metaphors about their students’ role using Leavy et al. (2007)’s categorization and metaphors about the accounting profession’s role).

The study relied on previous research that focused on accountants’ and auditors’ stereotypes (Caglio et al., 2019; Mellado et al., 2020; Richardson et al., 2015). The objective of this study is to analyze the perception of the accounting and auditing professions through personal metaphors drawn by students. The study also focuses on the changes that in-class interventions produce in students’ perceptions of their role as future accountants and auditors. Metaphors were obtained from an open questionnaire, in which students were asked to draw and describe their self-images about the professions. The analysis consisted of three phases: 1) we categorized the metaphors following Richardson et al. (2015)’s framework for the accounting and auditing profession; 2) we compared the two sets of results for accounting and auditing before and after in-class intervention; and 3) we analyzed the changes in the metaphors for accountants and auditors and also considered several students’ profiles and characteristics such as gender, age, job preference, and internship (i.e. if the student had done an internship). The analysis was based on 131 questionnaire responses from Spanish undergraduates.

In the European Union (E.U.) access to the auditing profession has been standardized and it is externally regulated although some member states retain individual features (Jahn and Loy, 2023). Conversely, the regulation of the accounting profession depends on the law in each separate country and there are major discrepancies across jurisdictions. In most Western European countries such as Belgium, France, Italy, Ireland and Portugal, the accounting profession is also regulated. The case of Spain is unique inside the European Union because the accounting profession is not an externally regulated activity. Moreover, Spain is a civil law country with a small number of listed corporations; small and medium sized companies are the main component of the economy (La Porta et al., 1998). That makes Spain an ideal setting to explore the analogies and variances in social perceptions of accountants compared to auditors through the drawings of business undergraduates because of its difference from other EU jurisdictions.

The evidence shows that most participants have traditional perceptions of accounting and auditing professionals. Most of the respondents believe that their personal visions are shared by those in the profession. Traditional vs. more contemporary vision, including resistance to change, is a matter of considerable interest for academia. Our results indicate that students have a more traditional idea of accountants than of auditors. There are also more metaphors with positive connotations for auditors than for accountants. The findings reveal that percentages of contemporary and positive perceptions increase after the in-class intervention and that future images of their professional selves are more optimistic for the auditing profession than for the accounting profession.

This study contributes to the existing literature by providing several new insights. First, this study validates the metaphor theory to identify and explain accounting stereotypes that have been scarcely applied in accounting and auditing studies. Second, the study contributes to a better understanding of the social image of accountants through the analysis of both accounting and auditing professions. The auditing profession in civil law countries such as Spain is characterized by an elevated degree of legalism and auditors follow a different career path and professionalization process and adopt different public roles than accountants do. This scenario, encompassing both profiles, has not been examined previously. Third, the study focused on class interventions; hence, it extends an understanding of changes in students’ perception of accounting stereotypes after introducing the intervention. Additionally, this study offers evidence outside the Anglo-American context, addressing calls for further studies in this area, including different cultural settings (Caglio et al., 2019; Espinosa-Pike et al., 2021; Leão and Gomes, 2022).

Summarily, this study provides several implications for the accounting and auditing profession, as well as for accounting education. The progression (or non-progression) in traditional vision toward a contemporary vision as well as the progression (or regression) in positive connotations associated with personal metaphor allows further advancement, not only for accounting research but also for society. The results of this study regarding the effort to revert the negatively biased image that discourages most suitable students from choosing the accounting and auditing profession as a career option are valuable for the accounting discipline and for society in general.

The paper is structured as follows. The second section outlines the theoretical background and provides a brief description of previous studies in the field. The third section explains the empirical strategy, including the method, the survey, and the variables codification. The fourth section presents the sample. The fifth section explains and discusses findings, followed by the conclusions and implications.

2. Literature review and research questions

2.1 The formation of stereotypes and metaphors theory

Professional identity and stereotypes are interrelated. Stereotypes are generalized perceptions of a group’s social identity, as studied by social psychologists (Tajfel, 1984). In a natural cognitive process, individuals are classified into social groups that are separated from the masses by any shared feature such as gender, age, or job, and afterward, all group members are stereotyped and portrayed by a set of personal and even physical traits (Hinton, 2000). Accounting professional identity is also formed by normative external features such as the possession of formal education or codified behavior, and the representation of their workers, associations, and firms (Picard et al., 2014). Different sources contribute to the formation of accounting stereotypes (a combination of cognitive, affective, cultural, and social factors), and once they are established, they are difficult to change because they become important to understand the world simplistically and structurally (Caglio et al., 2019; Espinosa-Pike et al., 2021). Stereotype expectations influence group members and lead to self-fulfilling prophecies (Friedman and Lyne, 2001).

Therefore, stereotypes influence students’ internal self-image as future accounting professionals. In this context, metaphors are considered excellent tools for introspection (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980). A metaphor is the substitution of a concept with another idea that has a certain relationship or similarity with it. The theoretical framework developed by Lakoff and Johnson (1980) transcends the restrictive use of metaphors as a linguistic resource and illustrates how human beings are creators of abstract concepts based on ideas and images linked to experience. They holistically perceive metaphors as an essential mechanism of the mind to interpret reality and construct new meanings. The use of personal metaphors may help people understand their beliefs about their present or future role as part of a social or professional group (Leavy et al., 2007; Mellado et al., 2020).

Business research has relied on cognitive metaphor theory since the 1980s (Clarke and Holt, 2017; Morgan, 1980). Specifically, Young (2013) emphasized the contributions of metaphors to accounting research, practice, and education. Similar to later authors, such as McGoun et al. (2007), Morgan (1988) interprets the accounting definitions using metaphors. However, studies on personal accounting professional identity using participants’ metaphors are currently scarce (see e.g., Gökgök, 2012; Mellado et al., 2020; Nowak, 2019; Goretzki et al., 2022). For example, Goretzki et al. (2022) found metaphors referring to the group of German controllers obtained from articles published in the “Controller Magazin” and in in-depth interviews. They identify metaphors that equate controllers with a “professional mission” such as “protecting” or “guiding” an organization. These metaphors were used as a form of identification with the profession and to generate the idea of a controller community, creating an image of homogeneity among a disparate group of professionals, which may establish a sense of belonging.

2.2 Accounting and auditing profession stereotypes

Existing studies have focused on determining how students perceive the accounting profession globally (Arquero and Fernández-Polvillo 2019; Caglio et al., 2019; Gökgök, 2012; Mellado et al., 2017; Mellado et al., 2020). Arquero and Fernández-Polvillo (2019) find that the preconceptions of Business Administration and Finance and Accounting students are far from the optimal scenario, which can limit learning or even result in failure or dropout. Mellado et al. (2020) illustrated that the sample of accounting students had the most traditional positive ideas of the accounting profession. Some studies report that students perceive the accounting profession with a traditional bias, such as merely technical, whereas other studies report different scenarios. Caglio et al. (2019) investigated 1,794 respondents comprising university students, newly employed accountants, and practicing accountants, and found that most of the first group has an image close to the bean counter stereotype and that the second group prefers the image of a modern professional. They also reveal that practicing accountants (with more than one year of experience in accounting firms) had the mental model of a “plain vanilla professional”, an uncovered third image. This means an honest and effective worker, but without exaggeration and neither boring nor fascinating. Gökgök (2012) reported several characteristics of accountant perceptions—dealing with numbers and calculations, working carefully and meticulously, or attitude that opposes ethical values.

Audit perception has also attracted researchers’ attention. Ott (2022) maintains that professional identity varies depending on the area of specialization within the accounting profession. Friedman and Lyne (2001) stated that the accountant’s image in non-fiction printed media was worse than that of the auditor. Jeacle (2008) focused on the Big Four and international professional accounting bodies’ enrollment literature, concluding that they created a new image that differs from the bean counter, that is, the young, glamorous, and social professionals not possessing the essential characteristics needed by an accountant, such as reliability and precision. Indeed, several authors observe a positive change in the professional image of students (Durocher et al., 2016) owing to the recruitment process of accounting firms that consider more commercial and less traditional images (Daoust, 2020). However, they suggested that the change should be done carefully so as not to damage the expected professionality (Guo, 2016). Nga and Wai Mun (2013) examined the image of auditors and their personal traits in a sample of students. The results revealed a positive image of auditors as leaders and ethical professionals. Aroztegi et al. (2024) highlight the audit context as a pertinent setting for investigating job-related attitudes and the perceived support of audit firms.

Researchers have also examined how accountants are represented in movies (Dimnik and Felton, 2006), popular music (Jacobs and Evans, 2012; Smith and Jacobs, 2011), humor (Bougen, 1994; Miley and Read, 2012), advertisements (Baldvinsdottir et al., 2009), literature (Carnegie and Napier, 2010; Evans and Fraser, 2012; Leão et al., 2019), and business press (Friedman and Lyne, 2001). For example, Dimnik and Felton (2006) identified five stereotypes in movies: dreamer, plodder, eccentric, hero, and villain. Carnegie and Napier (2010) conducted an analysis based on post-Enron literature and established two categories of stereotypes: the traditional accounting stereotype (bean counter) described with adjectives such as trusted, honest, integrity, dull, uncreative, uncommercial, and business professional stereotypes characterized by attributes such as business-focused, exciting, creative, pleasing clients easily, and opportunistic. Richardson et al. (2015) classified cultural images of the profession into four categories —traditional accountants with positive personality traits, bean counters with negative attributes, guardians, contemporary business professionals with positive personality traits, and modern professionals with negative attributes.

As explained by Richardson et al. (2015), the image or stereotype of professionals are based on the interplay of the functionality of the role and the character of the person that is doing it. Traditionally, accountants were assumed to perform repetitive procedural duties dealing with computation. Conversely, the contemporary business professional is presumed to be managerially oriented occupying top financial or advisory positions. In the traditional vision, Richardson et al. (2015) identified detrimental adjectives used to describe the professional such as boring, unimaginative, tight-fisted, socially awkward, or passive, all with negative connotations, and beneficial statements about accountants or auditors such as discipline, conservative, honesty, accuracy, identified as having positive connotations. In contrast, negative words such as liar, manipulative or corrupt and positive sentences such as having managerial, social, and analytical skills, critical judgement and integrity, versatility and generosity are associated with the contemporary vision. These findings were extracted by Richardson et al. (2015) after they analyzed 111 statements describing accounting professionals from 16 published articles that comprise references of films, music, books, humor, among other medias (Carnegie and Napier, 2010; Dimnik and Felton, 2006; Smith and Jacobs, 2011).

The traditional perception of accountants and auditors is emblematic and creates tension in the profession. However, existing studies focused on particular groups, such as auditor stereotypes or the accounting profession. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that focuses on both roles, accountant and auditor perception, analyzed using personal metaphors. Therefore, we formulate the following research questions:

RQ1: What are undergraduate students perceptions of the accounting professionals through the analysis of personal metaphors? Do they express traditional or contemporary stereotypes? Do they have positive or negative connotations? Do participants consider their metaphors about accounting professionals to be predominant in the profession and society?

RQ2: What are undergraduate students perceptions of the auditing professionals through the analysis of personal metaphors? Do they express traditional or contemporary stereotypes? Do they have positive or negative connotations? Do participants consider their metaphors about auditing professionals to be predominant in the professionand society?

RQ3: Are there differences in the stereotypes associated with personal metaphors comparing perceptions of accountants and auditors? Considering the traditional or contemporary stereotypes? Positive or negative connotations? Predominance in the profession and society?

2.3 Factors that influence accounting stereotypes

Considerable efforts have been made in accounting research to understand factors that influence the formation of accounting stereotypes. Sociological and psychological theories provide a useful framework for understanding the formation of, and factors that contribute to certain images and stereotypes. Extending a set of personality features, behaviors, and cognitive processes, existing accounting research has progressed in terms of accounting profession stereotypes. For example, Leão and Gomes (2022) examined the effect of a set of personality traits on accountant stereotypes. The evidence suggests that accounting stereotypes are driven mainly by conscientiousness. Notably, accounting is an occupation with social acceptance although it is not associated with high social status.

Research on auditor stereotypes, including the traditional characteristics of the accounting profession and specific characteristics of auditors, has been conducted (Espinosa-Pike et al., 2021; Jelinek and Boyle, 2022; Navallas et al., 2017). Navallas et al. (2017) found some positive images among Spanish undergraduate students, such as competence, order, assertiveness, thoroughness, discipline, and commitment. Jelinek and Boyle (2022) discovered some progress in audit profession stereotypes using a sample of 176 public accounting professionals. Evidence reveals that male public accountants are more sociable than males in other professions, and female public accountants are less sociable than females in other professions. Additionally, Espinosa-Pike et al. (2021) conducted a survey with 360 undergraduate Spanish students measuring three aspects of the auditing profession — the professional image, job, and career. They found that auditors are considered ethical and skilled professionals. Also, the job is considered interesting because it involves a variety of tasks and contributes to society. Finally, professional career is viewed as a challenging path.

Several studies have shown that individuals select their careers and occupations based on social representation (Byrne and Willis, 2005). Professional identity and personal metaphors are also influenced by personal experiences, teachers, or relatives. Metacognitive reflection on personal metaphors has been used for self-knowledge and change of mental conceptions and actions (Wan and Low, 2015). From this perspective, accounting education and instructors play an important role in orientation of students about future studies or jobs (Karlsson and Noela, 2022). For example, Navallas et al. (2017) found that students perceived auditors differently after being in contact with their daily work (e.g., more sociable, joyful, team member, humble, gentle, skilled, and less impulsive than before the activity).

Consequently, our study examines the perceptions of undergraduate students regarding accounting and auditing roles, through the analysis of personal metaphors, after in-class intervention. The study also examines the global accounting stereotypes based on students’ characteristics, such as gender, age, job preference, and internship, as well as an analysis before and after the in-class intervention. Therefore, we formulate the following research questions:

RQ4: Are there changes in undergraduate students’ perceptions of the accounting and auditing professionals through the analysis of personal metaphors after the in-class intervention? Are there changes considering traditional or contemporary stereotypes? Are there changes in the positive or negative connotations? Are there changes in the participants’ beliefs about the predominance of their metaphors in the profession and society?

RQ5: What are undergraduate students’ perceptions of the accounting and auditing professionals through the analysis of personal metaphors considering student characteristics? Regarding traditional or contemporary stereotypes? Positive or negative connotations? Are there changes after in-class intervention?

3. Empirical strategy

This section explains the empirical procedure adopted in this study, including the method, questionnaire, categorization, codification of the variables, and statistical analyses.

3.1. Method

In educational studies, the use of metaphor theory to identify individual mental models and changes has been validated (Leavy et al., 2007; Mellado et al., 2021). Following the seminal work of Lakoff and Johnson (1980), researchers in education have examined how metaphors reflect personal teaching-learning models and how new meanings or metaphors lead to new realities in class. The methodology is based on the seven steps of Low’s (Wan and Low, 2015) approach: 1) preparing participants, 2) eliciting metaphors, 3) categorizing metaphors, 4) connecting with theoretical orientation, 5) establishing behavior, 6) defining a plan for future actions, and 7) assessing changes in metaphors.

The metaphor approach is different from other methodologies. Metaphors specify the mental model of the participant in a symbolic concept, idea, subject, or object. The result of this exercise is a metaphor expressed in a drawing and explained in a text that highlights some aspects of the role of future professionals and ignores other traits (Young, 2013). This method has been also used in business and management (Clarke and Holt, 2017; Morgan, 1980) and accounting (Gökgök, 2012; Mellado et al., 2020; Nowak, 2019).

3.2. Questionnaire

Data were collected using a questionnaire that consisted of three parts including a cover letter and the objectives of the study, with instruction that the responses and personal information provided would be kept confidential. The first part of the questionnaire contained sociodemographic and job-related variables such as gender, age, preferred job, and internship (e.g., Byrne and Willis, 2005).

The second part of the questionnaire included four open questions related to metaphors:

Please make a simple drawing to express the metaphor(s) you would use to identify yourself as an accounting professional.

Please name and describe the above metaphor(s) and explain the reasons for your choice.

Please make a simple drawing to express the metaphor(s) you would use to identify yourself as an audit professional.

Please name and describe the above metaphor(s) and explain the reasons for your choice.

After the space to draw and write, students were asked two more yes or no questions for the accountant and for the auditor:

Do you think that your personal metaphor(s) is/are the predominant metaphor(s) in the profession?

Do you think that your personal metaphor(s) is/are the predominant metaphor(s) in society?

The questionnaire was administrated at two intervals during the semester: at the beginning before the intervention started and at the end of the intervention. During the course, the students were informed about the objectives of the study. All study subjects were volunteers and were guaranteed confidentiality and anonymity. Study participants provided consent to participate in this study. This study followed the ethical procedures for research with human participants.

3.3 Description of the in-class intervention

The in-class intervention was composed of two parts. In the first part of the intervention the students had the opportunity to speak with a professional with a career in accounting and auditing, who shared their experiences. During the session the students asked questions about the profession and discussed what skills were needed on their resumes. Prior literature has examined how the student interaction with the reality of the profession during their degree improves the image of professionals (Espinosa-Pike et al., 2021).

The second part consisted of a researcher's attempt to stimulate students' metacognitive reflection regarding their views of accountants and auditors through metaphors. The researcher encouraged the students to be conscious of their mental models and to attempt to understand the reasons behind them, by presenting some participants’ drawings collected in the pre-test and thinking collectively about their meaning and sources without categorizing or judging them. In other social fields, such as education, the introduction of metaphor reflection allowed prospective professionals to consider the potential of this tool and to think about their own models (Leavy et al., 2007; Mellado et al., 2021; Wan and Low, 2015).

3.4 Categorization

The analysis of students’ personal metaphors was driven by a combination of the meanings extracted from drawings and written explanations provided by participants. We used Richardson et al. (2015)’s stereotype classification to categorize study participants’ personal metaphors about their prospective views as members of the accounting and audit professions. Their division is based on the combination of the perception of job challenges and tasks for a worker that join together traditional or contemporary visions and personal characteristics that included valence connotations (see Appendix 1, Figure 1, and Figure 2 for some visual examples of metaphor categorization). Students’ drawings were divided into the following groups: traditional vs contemporary metaphors and positive vs negative perceptions (Mellado et al., 2020). The categorization is based on a deeper subclassification of the representations, as accountant and auditor metaphors present slightly different connotations. We identify clusters of metaphors conditioned by common characteristics or similar references according to their underlying ideas about the accounting and auditing professionals, like metaphors of inspiring figures, for example (Goretzki et al., 2022).

To allocate metaphors to categories, we studied the participants’ images and written explanations of drawings. The context and the meanings assigned by the participants should be analyzed. All categorizations were examined by at least two researchers. Some participants used more than one metaphor for accountants and auditors, which is common in this methodology. The examinations of all the metaphors expressed by each participant allowed for the ulterior analysis of the change in the models from the pre-test to the post-test and to compare views about accounting and auditing professionals (see Appendix 1, Figure 3, and Figure 4).

Table 1 exhibits the categorization process. Table 1 Panel A shows metaphors belonging to the traditional vision of the professionals. The analysis of drawings in which money is present, such as wallet, piggy bank, money bag, notes, magnet attracting money, money symbols, reveals that they are referring to the accountant’s action of registering and controlling all money outflows and inflows in the company. In their positive connotation, study participants mentioned, for example, someone cautious who takes care of a business’s money and in their negative connotation, they talked about someone obsessed with money. These metaphors have been classified as traditional in line with the previous literature (see Carnegie and Napier, 2010; Jacobs and Evans, 2012; Picard et al., 2014).

The most repeated metaphor expressed by the student has to do with some of the elements used daily while performing procedural tasks, such as an office, computer, calculator, Excel, watch, papers, numbers, etc. Some of these students also drew a worker in a suit and working long hours in the office. The selection of these metaphors exemplifies the classical stereotype as endorsed by previous research (Caglio et al., 2019; Friedman and Lyne, 2001; Gökgök, 2012; Mellado et al., 2020; Richardson et al., 2015) that conceives of the professional as a methodological and conservative scorekeeper dealing with calculations and numbers or even as a grey bean counter, doing repetitive work with limited social relevance. In many cases, the participants reflected a positive image of the accountant and auditor undertaking their daily tasks by adding adjectives such as control, order, competence, or analytical thinking. The same type of metaphor, a watch for instance, may have different connotations depending on the meaning that the participants gave to it. Some participants assigned positive attributes to this metaphor such as accuracy, dedication, and punctuality while another participant used it to reflect the long hours spent by the worker in a boring place doing repetitive tasks, a negative connotation. Metaphors are categorized negatively when referring to personality attributes such as mediocre, unmotivated, dull, uncreative, sedentary, tired, or exploited worker, or job characteristics such as monotonous, uninteresting, or repetitive work with no room for reasoning or creativity. For instance, here we included the robot metaphor referring to someone uncreative doing an automated job. Morgan (1980) introduced the representation of companies as machines that reflect a rigid, rational, automated, and predictable view of businesses. In our study, we observed fewer negative metaphors for auditors than accountants; however, auditors were also perceived as workers under a large amount of stress as expressed by a student who drew a frowning man in the office at night.

Table 1. Categorization

| Panel A. Categorization of traditional metaphors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional metaphors | Examples of metaphors | Accounting and auditing professional | Type | Common features | Some references |

| Money metaphors | wallet; piggy bank; notes | Accountant and auditor | Positive | Cautious professional that controls carefully the firm’s money. Professional working and obsessed with money. | Picard et al., 2014 Carnegie and Napier, 2010 |

| Professional instruments | calculator; papers; robot; clock | Accountant and auditor | Positive Negative | Trustworthy professional doing an accurate job with numbers. Lifeless and uncreative professional with a boring job. | Schwartz, 2020 Gökgök, 2012 |

| Filtering/ordering metaphors | coffee grinder; water purifying container | Only accountant | Positive Negative | Professional with an extraordinary ability to process data. - | Mellado et al., 2020 |

| Geometrical forms | line; cube; square | Accountant and auditor | Positive | Systematic professional who does a precise and fair work. Narrow-minded and rigid professional doing repetitive tasks. | Richardson et al., 2015 |

| Authority/power | soldier; police; father | Only auditor | Positive Negative | Professionals with authority to make others respect the rules. - | McCracken et al., 2008 |

| Zoomorphic metaphors | turtle; dog; spider web; ant | Accountant and auditor | Positive Negative | Hard-working conservative professional with ability to control. - | Nowak, 2019 |

| Others | hammer; Tetris; dartboard | Accountant and auditor | Positive Negative | Accurate, consciousness and honest professional with a numbers job. Lonely and boring professional doing a repetitive and useless job | McGoun et al., 2007 Mellado et al., 2020 |

| Panel B. Categorization of contemporary metaphors | |||||

| Contemporary metaphors | Examples of metaphors | Accounting and auditing professional | Type | Common features | Some references |

| Inspirational figures and professionals | astronaut; superhero | Accountant and auditor | Positive Negative | Perseverant and competent business leader with a great job. - | Dimnik and Felton, 2006 |

| Justice metaphors | detective; judge; lens | Only auditor | Positive Negative | Skilled professional with a strong sense of justice and service. - | Richardson et al., 2015 |

| Social metaphors | family; handed people | Accountant and auditor | Positive Negative | Professional with managerial and social skills in an organization. - | Jelinek and Boyle, 2022 |

| Constructions and transports | house; column; aeroplane | Accountant and auditor | Positive Negative | Solid and effortful professional in an active and dynamic profession. Burned professional in a demanding job with too many travels. | Picard et al., 2014 |

| Parts of the body | brain; hand | Accountant and auditor | Positive Negative | Managerial & counsellor knowledge skilled business professional. - | Mellado et al., 2020 |

| Natural elements and animals | mountains; tree; sun | Accountant and auditor | Positive Negative | Colorful and perseverant professional with a challenging career. - | Jeacle, 2008 |

| Others | dreamer; lighthouse | Accountant and auditor | Positive Negative | Successful, constant and moral leader with an inspiring career. - | Goretzki et al., 2022 |

Furthermore, students chose a variety of metaphors that have the same meaning of filtering, unravelling, organizing, and categorizing data or information to maintain balance, such as a juggler, genius, water purifying container, wool ball, scale, labyrinth, tennis match, boxing ring, beach lifeguard, coffee grinder, bobbin lace, and digestive system. These kinds of positive metaphors, used only for the accounting profession, highlight the expertise of accounting and auditing professionals to process data. In contrast, some participants drew geometrical forms and lines for accounting and auditing role representing rigidity, monotony, narrow-mindedness, and inflexible people such as the metaphors of the straight line and the cube that have negative meanings.

There is a body of metaphors used only for the auditing profession, such as policeman or soldier where the use of force to control and apply mandates is permitted. This is considered a traditional public watchdog auditing approach that scores the highest in the ethical dimension. Other metaphors emphasize the auditor’s paternalistic attitude, such as the father playing with a baby. McCracken et al. (2008) found that partners at the audit firms want to change this reactive image of police officers to a more proactive one. However, there is debate in the accounting literature on how this change might affect the professional and ethical attributes of an auditor, such as independence and compliance with the rules (Guo, 2016).

Some zoomorphic metaphors where professionals are compared to animals (Nowak, 2019) can also be classified as traditional metaphors. For example, a few students chose the ant metaphor for the accounting profession that represents a hard-working professional, which is a positive personality trait, with a necessary but repetitive job within a very hierarchical structure. Previous research has analyzed the same metaphor (Gökgök, 2012; Nowak, 2019). Another student chose the turtle metaphor, a very self-centered metaphor, to reveal their conservative professional projection as an accountant moving slowly but surely.

Second, Table 1 Panel B shows the categorization of contemporary metaphors. Here, the professional identity evolves from doing bureaucratic tasks to the highly skilled executive (Richardson et al., 2015). Modern business professionals combine expertise, knowledge, and attitudes such as determination to become excellent professionals (Caglio et al., 2019). A positive professional profile is required for expertise in different areas with high ratings for ethical, social, skill, and service dimensions (Richardson et al., 2015). There is a body of positive metaphors where participants compare the accounting profession with idealized and recognized professionals in their fields. For instance, the metaphor of the astronaut drawn by a student symbolizes the heart of the space mission, the brave person who put theory into practice. One figure that brings together all the positive attributes is that of the superhero, considered an action-oriented leader, a contemporary positive metaphor often mentioned in the literature (Dimnik and Felton, 2006; Jacobs and Evans, 2012; Picard et al., 2014).

Moreover, some of the personal metaphors chosen by the study participants only for the auditing profession emanated from their sense of justice. The judge metaphor is similar to the guardian metaphor mentioned by Richardson et al. (2015). They are trustworthy and ethical, dedicated to protecting the public interest and maintaining their independence from internal or external influences. Similarly, the scale metaphor was chosen by a student because it represents balance and justice. Additionally, the metaphors of eyes and lens highlight attributes such as the objectivity and transparency of auditors and emphasize the importance of their job for society.

Few students drew social metaphors. For example, the metaphor of the round table surrounded by chairs refers to a sense of belonging and the need for teamwork to achieve goals. Likewise, the metaphor of the family considers auditors as relatives that support and help each other when the need arises. Jelinek and Boyle (2022) argued that public accounting firms’ professionals suit the definition of “boundary spanners,” combining proficient technical knowledge with honed social skills to interact with clients. This reflects dynamic work in which auditors must adapt to each client.

Some participants chose symbols of construction and transportation. One study participant chose the metaphor of the building of a house, referring to the desire to improve through hard work and continuous learning to be promoted over their career. Two participants identified the accounting professional with a column in an ancient temple. The meaning of the metaphor is that the accounting professional or team holds up the weight of keeping the business standing for a long time along with other professionals or departments of the company. Audit metaphors about transportation such as train tracks or airplanes reflect an active profession in contact with different sectors and companies. Generally, they are considered positive; however, in some cases, they are considered negative because the student associates the metaphor with an unstable lifestyle, stress, and discomfort.

There are a group of metaphors that mention natural elements and animals. There is a metaphor that refers to the challenges of climbing a mountain. It has been used previously in accounting, education, and management (Mellado et al., 2020) and has been classified as contemporary. It implies perseverance and similar attitudes in pursuit of the accounting profession and emphasizes the difficulties to overcome in the process of becoming an exceptional worker in a dynamic job that needs education and training. Moreover, the metaphor of the tree suggests continuous growth and career progress and has been used previously (Clarke and Holt, 2017). It is connected to a metaphor that views the entity as a living organism (Morgan, 1980). We also categorize some of the students’ drawings representing natural elements such as the sun and the moon as contemporary metaphors because they refer to excellent professionals. These metaphors are close to the colorful image of the accountant shown in the work of Jeacle (2008), a more glamorous and sociable version of the accountant spread by audit firms.

In the cluster of parts of the body, we find the brain that highlights managerial skills and the ability to exert an influence. Comparably, in the metaphor of the hand with a gift, the student conceives the image of his auditor role as a company helper similar to the ideal proactive image of an expert advisor (McCracken et al., 2008). Considering other contemporary metaphors, the dreamer metaphor was drawn by a student who idealizes the accounting and the auditing profession. Spanish undergraduate business students consider the auditing profession to be an attractive one, with many opportunities inside and outside firms for professional development (Espinosa-Pike et al., 2021). The lighthouse is a metaphor for the auditor’s role as a guide (also mentioned by Goretzki et al., 2022), often used in education (Mellado et al., 2021) in the constructivist category, like North Stars (Leavy et al., 2007).

3.5 Variables codification

First, we classified participants’ answers according to metaphor drawings by students to describe the role of accounting (auditing). Based on the study published by Richardson et al. (2015), we classified metaphors into contemporary and traditional. Specifically, we defined a dummy that takes the value of 1 when the metaphor refers to a contemporary business professional, and 0 when the metaphor refers to a traditional accountant.

Second, we examined the positive (negative) perception of the metaphor chosen by the student to describe the accounting (auditing) role. We defined a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the perception associated with the metaphor was not negative, and 0 otherwise. We considered perceptions associated with the accounting and audit profession.

Third, we analyzed whether the participants considered their personal metaphors about accounting and auditing professionals as predominant in the profession and society. We defined a dummy that takes the value of 1 when the participant feels that the personal metaphor(s) he/she selected is/are predominant in the profession, and 0 otherwise. And we identified another dummy that takes the value of 1 when the participant understood that the personal metaphor(s) he/she selected is/are predominant in society at large, and 0 otherwise.

Fourth, we studied changes in metaphors before and after the intervention in class. Therefore, we defined a dummy variable for identifying the period before and after the intervention in class, which takes the value of 1 for the pre-test, and 0 for the post-test.

Fifth, we examined the differences between personal metaphors for accountants and auditors, and the dummy variable took the value 1 for accountant metaphors, and 0 for auditor metaphors.

Sixth, we analyzed the relationship between the metaphor drawings by the students according to the criteria explained above and the students’ characteristics. In this stage, we included variables such as gender, age, job preference, and internship. The codifications of the variables were as follows:

Gender was measured as a dummy variable assigned the value of 1 for female students, and 0 for male students.

Age was measured as a dummy variable assigned the value of 1 for students under 23 years, and 0 for students aged 23 years or older.

Job preference was measured as a dummy variable assigned the value of 1 when participants indicated a preference for an accounting/auditing job, and 0 otherwise.

Internship was measured as a dummy variable assigned the value of 1 if the student did an internship during their degree (i.e. if the student had already finished the internship or if the participant was doing it when filling out the questionnaire), and 0 otherwise. In the last year of the degree in Business Administration, the students can take an optional course called “Outside Internships” monitored by an academic tutor as a curricular activity. This allows students to do an internship in a company (in accounting/auditing and other business areas) that has an agreement with the university and be tutored and evaluated. There is an office at the university that organizes and helps students to do internships.

This study used contingency tables and Pearson’s chi-square test to examine the relationship between the categorical variables of our study and student profiles and characteristics. We considered statistically significant associations at conventional statistical levels (p < 0.05) and marginal statistical associations (p < 0.10).

4. Sample and descriptive statistics

We collected 131 responses (74 in the pre-test and 57 in the post-test) from Spanish students enrolled in the last year of their Business Administration degree in the second semester of 2021.

Table 2. Sample and characteristics of study participants.

| Students’ characteristics | Pre-test | Post-test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | % | Frequency | % | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Men | 44 | 59.46% | 33 | 57.89% | ||

| Women | 30 | 40.54% | 24 | 42.11% | ||

| Total | 74 | 100.00% | 57 | 100.00% | ||

| Age | ||||||

| Less than 23 | 45 | 60.81% | 29 | 50.88% | ||

| 23 or more | 29 | 39.19% | 28 | 49.12% | ||

| Total | 74 | 100.00% | 57 | 100.00% | ||

| Preferred job | ||||||

| Account/audit profession | 28 | 37.84% | 18 | 31.58% | ||

| Non-account/audit profession | 40 | 54.05% | 37 | 64.91% | ||

| No answer | 6 | 8.11% | 2 | 3.51% | ||

| Total | 74 | 100.00% | 57 | 100.00% | ||

| Internship during degree | ||||||

| Yes | 20 | 27.03% | 26 | 45.61% | ||

| No | 50 | 67.57% | 31 | 54.39% | ||

| No answer | 4 | 5.41% | 0 | 0.00% | ||

| Total | 74 | 100.00% | 57 | 100.00% | ||

Table 2 shows that 59.46% respondents in the pre-test and 57.89% in the post-test were men, and 40.54% in the pre-test and 42.11% in the post-test were women. Most students were under 23 years old (60.81% in the pre-test and 50.88% in the post-test). 28 students in the pre-test and 18 students in the post-test preferred a job related to accounting, while 20 students in the pre-test and 26 students in the post-test had been undergoing an internship during the degree. We found some discrepancies due to the different number of participants pre-test to post-test and in some cases, there were a few changes (for example, in the data panel, only four students changed their job preferences, choosing a profession close to accounting or auditing but not exactly accounting or auditing).

5. Results and discussion

5.1 Perceptions of the accounting and auditing professions

To answer the first research question, we showed the perceptions of undergraduate students about their future roles as accountants through the analysis of their personal metaphors confirming the fact that participants could express their thinking using images. The personal metaphors were classified according to the categorization described in section 3. The results were divided into the following categories: traditional vs contemporary metaphors; positive vs negative connotations; and predominance in the profession and society.

Table 3. Results of metaphor codification for accounting professional’s role before in-class intervention

| Traditional vs contemporary | N | % | Positive vs negative connotations | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional accountant | 68 | 83.95% | Positive connotation | 68 | 83.95% | |

| Contemporary business professional | 13 | 16.05% | Negative connotation | 13 | 16.05% | |

| Total | 81 | 100.00% | Total | 81 | 100.00% | |

| Metaphors in the profession | N | % | Metaphors in society | n | % | |

| Predominant in the profession | 55 | 67.90% | Predominant in society | 29 | 35.80% | |

| Traditional | 45 | 55.56% | Traditional | 25 | 30.86% | |

| Contemporary | 10 | 12.35% | Contemporary | 4 | 4.94% | |

| No predominant in the profession | 18 | 22.22% | No predominant in society | 39 | 48.15% | |

| Traditional | 16 | 19.75% | Traditional | 33 | 40.74% | |

| Contemporary | 2 | 2.47% | Contemporary | 6 | 7.41% | |

| No answer | 8 | 9.88% | No answer | 13 | 16.05% | |

| Total | 81 | 100.00% | Total | 81 | 100.00% | |

Table 3 indicates that 83.95% of metaphors selected by students convey a traditional view of accounting as a profession and 16.05% express a contemporary view of it. Other studies, such as Caglio et al., (2019), Mellado et al., (2020) and Wessels and Steenkamp’s (2009) found that the traditional vision of students predominates the contemporary vision.

Regarding the positive or negative perceptions associated with personal metaphors, the results showed that most metaphors represent a positive perception of accounting (83.95%, Table 3). The analysis of the drawings showed that participants did not associate any negative contemporary metaphor with accountants according to the framework established by Richardson et al. (2015), i.e. a highly competent professional but one who is dishonest or manipulative (see the villains in movies as shown by Dimnik and Felton, 2006 and the evil depicted in popular music lyrics indicated by Smith and Jacobs, 2011).

In addition, Table 3 shows that 67.90% of the metaphors selected by students for the accounting profession are considered by them as predominant metaphors in the profession – traditional 55.56% and contemporary 12.35% –, whereas the percentage of metaphors not considered predominant was 22.22%. However, when considering students’ opinions of the predominance of their personal metaphors in society, the percentages decreased to 35.80% (traditional 30.86%; contemporary 4.94%), while the percentage of metaphors not predominant in society increased to 48.15%.

To answer the second research question, we showed the perceptions of undergraduate students about their future role as auditors through the analysis of their personal metaphors confirming the fact that study participants used images to express their mental models. The personal metaphors were classified according to the categorization described in Section 3.

Table 4. Results of metaphor codification for auditing professional’s role before in-class intervention

| Traditional vs contemporary | n | % | Positive vs negative connotations | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional auditor | 54 | 71.05% | Positive connotation | 70 | 92.11% | |

| Contemporary business professional | 22 | 28.95% | Negative connotation | 6 | 7.89% | |

| Total | 76 | 100.00% | Total | 76 | 100.00% | |

| Metaphors in the profession | n | % | Metaphors in society | n | % | |

| Predominant in the profession | 53 | 69.74% | Predominant in society | 38 | 50.00% | |

| Traditional | 37 | 48.68% | Traditional | 29 | 38.16% | |

| Contemporary | 16 | 21.05% | Contemporary | 9 | 11.84% | |

| No predominant in the profession | 13 | 17.11% | No predominant in society | 26 | 34.21% | |

| Traditional | 11 | 14.47% | Traditional | 17 | 22.37% | |

| Contemporary | 2 | 2.63% | Contemporary | 9 | 11.84% | |

| No answer | 10 | 13.16% | No answer | 12 | 15.79% | |

| Total | 76 | 100.00% | Total | 76 | 100.00% | |

Table 4 shows that 71.05% of metaphors selected by students reflect a traditional view of auditing as a profession and 28.95% reflect a contemporary view of it. Table 4 reveals that 92.11% of the metaphors express a positive connotation and 7.89% express a negative connotation. We found a new group of metaphors aligning the view of auditors with a strong compliance and ethics dimension. First, we identified the image of police officers classified as traditional and second, the guardian subtype represented by the judge or scale metaphors and classified as contemporary. Table 4 shows that 69.74% are metaphors predominant in the auditing profession – 48.68% traditional and 21.05% contemporary–, while 17.11% are not predominant in the profession. Nevertheless, 50.00% of metaphors about audit professionals are considered predominant in society –traditional 38.16% and contemporary 11.84%– while 34.21% are considered personal metaphors only.

To answer the third research question, we compared the perceptions of undergraduate students about accounting and auditing professionals. In particular, the role of the accounting profession (traditional and contemporary), including both predominant and non-predominant metaphors, the role of the auditing profession (traditional and contemporary), including both predominant and non-predominant metaphors, and perceptions associated with metaphors (positive and negative), considering accounting and auditing preconceptions.

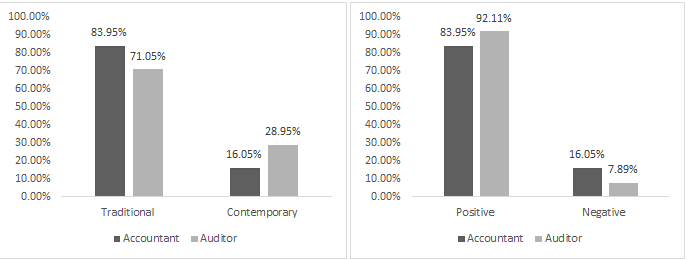

Charts 1 and 2. Comparison of undergraduate students perceptions of accounting and auditing professionals

Charts 1 and 2 show the comparison of the personal metaphors representing the accounting and auditing profession roles. The results show that students have a more traditional view of the former than the latter. Regarding the positive or negative perceptions associated with personal metaphors, the results show that most metaphors represent a positive perception of the accounting (83.95%, Table 3) and auditing profession (92.11%, Table 4). The results for the positive perceptions of the auditing profession are higher than for the accounting profession. The Chi-square is significant (p < 0.05) in terms of type of personal metaphors –traditional vs contemporary and positive vs negative perception– comparing the accounting and auditing professions in aggregate terms.

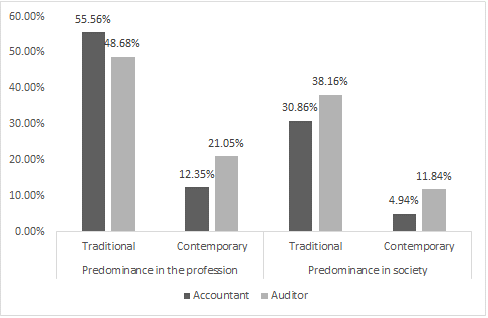

Chart 3. Students beliefs about the predominance of their metaphors in the profession and in society

Chart 3 presents students' beliefs about the predominance of their metaphors in the profession and in society, considering both roles (accountant and auditor). The results show that 55.56% of traditional metaphors about accounting professionals are believed to be shared in the profession while 48.68% of traditional metaphors about auditing professionals are considered predominant in the profession. In contrast, regarding predominant beliefs in society, the percentage of traditional metaphors about the auditors’ role is higher (38.16%) than the percentage of traditional metaphors about the accountants’ role (30.86%). Only 12.35% and 4.94% of contemporary metaphors about accounting professionals are considered predominant in the profession and society respectively while the percentage increases regarding metaphors about auditing professionals (21.05% in the profession and 11.84% in society).

5.2 Changes in perceptions of accounting and auditing professionals after in-class intervention

To answer the fourth research question, Table 5 presents the classification of participants’ metaphors after the in-class intervention. Table 5 Panel A shows that 80.95% of metaphors relied on traditional stereotypes about accountants and 19.05% relied on contemporary stereotypes about accountants. Although the Chi-square is not significant (p > 0.05), we find that the percentage of students that chose contemporary metaphors was higher after the class-intervention. Table 5 Panel B reveals that 63.33% of metaphors invoke traditional images about the auditing profession and 36.37% invoke contemporary images about the auditing profession. Here, the class intervention was more effective as the percentage of contemporary images went from 28.95% to 36.67%.

Table 5. Results of metaphor codification for accounting and auditing professional’s role after in-class intervention

| Panel A. Results for accounting professional’s role | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional vs contemporary | n | % | Positive vs negative perception | N | % | |

| Traditional accountant | 51 | 80.95% | Positive perception | 57 | 90.48% | |

| Contemporary business professional | 12 | 19.05% | Negative perception | 6 | 9.52% | |

| Total | 63 | 100.00% | Total | 63 | 100.00% | |

| Metaphors in the profession | n | % | Metaphors in society | N | % | |

| Predominant in the profession | 44 | 69.84% | Predominant in society | 24 | 38.10% | |

| Traditional | 36 | 57.14% | Traditional | 20 | 31.75% | |

| Contemporary | 8 | 12.70% | Contemporary | 4 | 6.35% | |

| No predominant in the profession | 14 | 22.22% | No predominant in society | 30 | 47.62% | |

| Traditional | 11 | 17.46% | Traditional | 24 | 38.10% | |

| Contemporary | 3 | 4.76% | Contemporary | 6 | 9.52% | |

| No answer | 5 | 7.94% | No answer | 9 | 14.29% | |

| Total | 63 | 100.00% | Total | 63 | 100.00% | |

| Panel B. Results for auditing professional’s role | ||||||

| Traditional vs contemporary | n | % | Positive vs negative connotations | N | % | |

| Traditional auditor | 38 | 63.33% | Positive connotation | 59 | 98.33% | |

| Contemporary business professional | 22 | 36.67% | Negative connotation | 1 | 1.67% | |

| Total | 60 | 100.00% | Total | 60 | 100.00% | |

| Metaphors in the profession | n | % | Metaphors in society | N | % | |

| Predominant in the profession | 41 | 68.33% | Predominant in society | 29 | 48.33% | |

| Traditional | 28 | 46.67% | Traditional | 19 | 31.67% | |

| Contemporary | 13 | 21.67% | Contemporary | 10 | 16.67% | |

| No predominant in the profession | 9 | 15.00% | No predominant in society | 19 | 31.67% | |

| Traditional | 3 | 5.00% | Traditional | 11 | 18.33% | |

| Contemporary | 6 | 10.00% | Contemporary | 8 | 13.33% | |

| No answer | 10 | 16.67% | No answer | 12 | 20.00% | |

| Total | 60 | 100.00% | Total | 60 | 100.00% | |

Table 5 also reveals that 90.48% of students express positive connotations about the accounting profession (Panel A), and 98.33% express positive connotations about the auditing profession (Panel B). Both percentages were higher after the in-class intervention. The positive connotation for the auditing profession is very high (98.33%), with only one student giving a negative connotation. The results also show that positive connotations increased after the in-class intervention. Regarding the accounting profession, the percentage of the responses in the pre-test was 83.95%, and the percentage of the responses in the post-test was 90.48%. Looking at the auditing profession, the percentage of the responses in the pre-test was 92.11% and the percentage of the responses in the post-test 98.33%. The evidence suggests that in-class intervention improves students’ perceptions.

Moreover, Table 5 Panel A confirms that in the post-test 69.84% of accounting professional metaphors were seen as predominant in the profession –traditional 57.14% and contemporary 12.70%– while only 38.10% of the metaphors were considered representative in society. Regarding metaphors about the auditing profession, Table 5 Panel B indicates that 68.33% of the audit profession metaphors are believed to be representative in the profession and 48.33% of the metaphors to be the general image in society.

In Charts 4 and 5, we compare the results before and after the in-class interventions, i.e. the changes in the metaphors and their categorization before and after the class intervention. Chart 4 shows that participants present a higher percentage of traditional models about accountants before the intervention (83.95%) than after the intervention (80.95%). Although the Chi-square is not significant (p > 0.05), we found that the percentage of students that chose a contemporary metaphor regarding the accountants’ role was higher after the in-class intervention (19.05%) than before (16.05%). With regards to the auditors’ role, we find the in-class intervention was more effective; contemporary images went from 28.95% to 36.67%. In other words, we found a decrease in the percentage of traditional metaphors (from 71.05% to 63.33%).

Chart 4 and 5. Changes in undergraduate students perceptions of the accounting and auditing professionals from the pre-test to the post-test

Chart 5 also shows that the percentage of students expressing positive connotations about the accountant’s role in the pre-test was 83.95%, and the percentage of responses in the post-test was 90.48%. For the auditing profession, the percentage of positive connotations went from 92.11% in the pre-test to 98.33% in the post test, which is very high, with only one student expressing a negative connotation. Both results show that positive connotations increased after the in-class intervention, what suggests that it may improve student perceptions.

Chart 6. Changes in undergraduate students beliefs about the predominance of their perceptions about accounting and auditing professionals from the pre-test to the post-test

Chart 6 exhibits that the percentage of students believing their contemporary metaphors are predominant increased slightly in general in the post-test.

Therefore, the university offers a unique setting for promoting some changes. Instructors should regard the teaching–learning process not only as a means for developing academic competencies but also as a critical avenue for fostering students’ critical thinking skills and changing some student’ preconceptions. This aligns with prior research in the field of accounting such as the studies by Espinosa-Pike et al. (2021), Blasco Burriel et al. (2023) and Mellado et al. (2021).

Perception of accounting and auditing professionals by student profile and characteristics

This section answers the last research question by examining the results according to students’ profile and characteristics: gender, age, job preference, and internship during their studies. We used contingency tables and Pearson’s chi-square test to examine the relationship between the categorical variables of our study and students’ characteristics. The study also analyzes the accounting global stereotypes conditioned to students’ characteristics before and after the in-class intervention to observe their evolution.

There was no significant relationship between accountants and auditors (p > 0.05) by gender in either the pre-test or post-test (p > 0.05). However, Table 6 Panel A, shows that males present a high percentage of traditional models about accountants before the intervention (87.23%) compared to the percentage after the intervention (80.00%). In other words, the percentage of responses of contemporary perception was lower in males before the intervention (32.26%) than after the intervention (42.31%). This can be interpreted as a positive evolution in accounting perception and is consistent with the findings of Byrne and Willis (2005) that women present a higher percentage of traditional models than men. In contrast, Panel A in Table 6 exposes that females present a high percentage of traditional models of auditors (67.74%) compared to the percentage after the intervention (57.74%). In other words, there is an evolution in the contemporary model (from 32.26% to 42.31%). Considering the positive and negative perceptions of accountants and auditors, women present higher percentages than men in accountant and auditor images. This confirmed previous findings by Caglio et al. (2019) and Mellado et al. (2020). It was also observed that the percentage of women increased after the intervention (from 85.29% to 96.43%).

Regarding the age variable, the Chi-square analysis showed a significant relationship (p < 0.05) in the pre-test and post-test considering personal metaphors for accountants. Indeed, Table 6 Panel B shows that older students present more traditional perceptions about accountants (93.94%) than less mature students (77.08%) in the pre-test and post-test (93.55% and 68.75% respectively). Interestingly, the older students hardly changed their perceptions about traditional accounting, while the younger students were more sensitive to changing their perceptions about traditional accounting. Indeed, the results showed that after the in-class intervention, the percentage of responses of contemporary perception increased from 22.92% to 31.25% in younger students. Chi-square analysis showed no significant relationship (p > 0.05) in the perception of the auditing profession. It is also noted that older students presented a more traditional vision (73.33%) than younger students (69.57%). In this case, the intervention had similar effects on both groups (Table 6 Panel B). In terms of positive or negative perceptions associated with personal metaphors for accountants and auditors, the statistical test showed no significant relationship, but the positive perception associated with the traditional model increased among the younger students.

Table 6. Results of metaphor codification by gender and age

| Panel A. Results by gender | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Female | Male | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pre-test | Post-test | Pre-test | Post-test | Pre-test | Post-test | Pre-test | Post-test | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Account | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | Account | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tradition | 27 | 79.41% | 23 | 82.14% | 41 | 87.23% | 28 | 80.00% | Positive | 29 | 85.29% | 27 | 96.43% | 39 | 82.98% | 30 | 85.71% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Contemp | 7 | 20.59% | 5 | 17.86% | 6 | 12.77% | 7 | 20.00% | Negative | 5 | 14.71% | 1 | 3.57% | 8 | 17.02% | 5 | 14.29% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Auditor | Auditor | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tradition | 21 | 67.74% | 15 | 57.69% | 33 | 73.33% | 22 | 64.71% | Positive | 29 | 93.55% | 26 | 100.00% | 41 | 91.11% | 33 | 97.06% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Contemp | 10 | 32.26% | 11 | 42.31% | 12 | 26.67% | 12 | 35.29% | Negative | 2 | 6.45% | 0 | 0.00% | 4 | 8.89% | 1 | 2.94% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Panel B. Results by age | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Female | Male | Female | Male | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pre-test | Post-test | Pre-test | Post-test | Pre-test | Post-test | Pre-test | Post-test | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Account | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | Account | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tradition | 37 | 77.08% | 22 | 68.75% | 31 | 93.94% | 29 | 93.55% | Positive | 41 | 85.42% | 28 | 87.50% | 27 | 81.82% | 29 | 93.55% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Contemp | 11 | 22.92% | 10 | 31.25% | 2 | 6.06% | 2 | 6.45% | Negative | 7 | 14.58% | 4 | 12.50% | 6 | 18.18% | 2 | 6.45% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Auditor | Auditor | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tradition | 32 | 69.57% | 20 | 62.50% | 22 | 73.33% | 17 | 60.71% | Positive | 43 | 93.48% | 32 | 100.00% | 27 | 90.00% | 27 | 96.43% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Contemp | 14 | 30.43% | 12 | 37.50% | 8 | 26.67% | 11 | 39.29% | Negative | 3 | 6.52% | 0 | 0.00% | 3 | 10.00% | 1 | 3.57% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||