Towards a conceptualised belief-action-outcome model for enhanced non-financial reporting: A systematic and integrative review

ABSTRACT

This study aims to advance knowledge in the field of non-financial reporting (NFR) research by examining how academic and business insights into the qualitative dimensions of NFR have shaped the requirements of the new CSRD (Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive) and its desired outcome of increased transparency.

The research design enriches scholarship by combining the methodologies of systematic and integrative literature review, and lays the foundations for a conceptual model based on a literature taxonomy to support further research.

This study represents the first attempt to empirically address the links between academics, business practitioners and regulators by integrating them into an original conceptual model based on the Belief-Action-Outcome framework. It highlights the interconnectedness between the cognitive, attitudinal and behavioural dimensions of the tripartite relationship derived from the literature taxonomy using partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM).

The results reveal meaningful relationships between the three perspectives, as hypothesised, which shed light on the valuable contributions of academics to the NFR regulatory process. Specifically, academic insights into the qualitative dimensions of NFRs positively influenced the requirements of CSRD and its outcome of increased transparency. In addition, practitioners' attitudes expressed through public consultations on NFRD reinforced this outcome through their positive moderating effect.

The study is relevant to regulators, practitioners and academics interested in engaging in challenging debates about sustainability reporting. It catalyzes understanding the link between academic and real-world evidence, supporting regulatory progress, and leading to a virtuous cycle of value creation and meaningful communication.

Keywords: Non-financial information; Disclosure quality; Corporate sustainability reporting; Belief-action-outcome framework; Literature review; PLS-SEM modelling.

JEL classification: Q5; Q01.

Hacia un modelo conceptualizado de creencia-acción-resultado para la mejora de la información no financiera: Una revisión sistemática e integradora

RESUMEN

El objetivo de este estudio es avanzar en el conocimiento de la investigación sobre la información no financiera (IRNF), investigando el modo en que las ideas académicas y empresariales sobre las dimensiones cualitativas de la IRNF han dado forma a los requisitos de la nueva Directiva sobre la elaboración de informes de sostenibilidad de las empresas (CSRD, por sus siglas en inglés) y a su resultado deseado de aumentar la transparencia.

El diseño de la investigación enriquece la literatura existente al combinar las metodologías de revisión bibliográfica sistemática e integradora, sentando las bases de un modelo conceptualizado basado en una taxonomía bibliográfica destinada a respaldar futuras investigaciones.

Este estudio representa el primer intento de abordar empíricamente las conexiones entre los académicos, los profesionales de la empresa y los organismos reguladores, integrándolas en un modelo conceptualizado original basado en el marco Creencia-Acción-Resultado. En concreto, pone de relieve la interconexión entre las dimensiones cognitiva, actitudinal y conductual de la relación tripartita derivada de la taxonomía bibliográfica, utilizando la modelización de ecuaciones estructurales por mínimos cuadrados parciales (PLS-SEM).

Los resultados revelan conexiones significativas entre las tres perspectivas, según la hipótesis formulada, que arrojan luz sobre las valiosas contribuciones del mundo académico al proceso regulador de los NFR, fomentando un sentimiento de confianza y un mayor desarrollo. En concreto, los conocimientos académicos sobre las dimensiones cualitativas de los NFR influyeron positivamente en los requisitos del CSRD y en su resultado de mejora de la transparencia. Además, las actitudes de los profesionales expresadas a través de consultas públicas sobre el NFRD reforzaron este resultado debido a su efecto moderador positivo.

El estudio es relevante para los reguladores, los profesionales y el mundo académico interesados en participar en debates estimulantes sobre la elaboración de informes de sostenibilidad. Sirve de catalizador para comprender el vínculo entre las pruebas científicas y las del mundo real, apoyar los avances en la normativa y orientar hacia un ciclo positivo de creación de valor y comunicación significativa.

Palabras clave: Información no financiera; Calidad de la información; Información sobre sostenibilidad empresarial; Marco creencia-acción-resultado; Revisión bibliográfica; Modelización PLS-SEM.

Códigos JEL: Q5; Q01.

1. Introduction

Non-financial reporting (NFR) initially emerged from voluntary actions by organisations to disclose information on social and environmental matters (Martínez-Córdoba et al., 2020; Benito et al., 2023; Arif et al., 2022; Santamaria et al., 2021; Guthrie & Parker, 2017). It has become increasingly important in promoting sustainable development practices worldwide (Pizzi et al., 2022; Mio et al., 2020). NFR encompasses different interrelated forms (e.g. corporate social/integrated/sustainability reporting). Both researchers and practitioners often use these terms interchangeably due to the vagueness of the concepts involved (Baumuller & Soop, 2022). However, despite the lack of a specific consensus, organisations have actively engaged in the voluntary disclosure of non-financial information (La Torre et al., 2018; Dienes et al., 2016) to increase transparency and accountability to stakeholders (Michelon et al., 2022). These practices have triggered academic debates on the quality of disclosure, addressing the complexity and subjectivity of this multifaceted concept (Stefanescu et al., 2021; Fiandrino et al., 2022; Aureli et al., 2019). In short, voluntarism may lack objectivity, comparability, completeness, neutrality and accuracy (Venturelli et al., 2019). The shift from voluntary disclosure to mandatory regulation was driven by the demonstrated need for transparency and rigour in the information disclosed (Ottenstein et al., 2022; Caputo et al., 2021; Stefanescu, 2022). However, the debate on voluntary versus mandatory disclosure is still ongoing at the academic and policy level (Korca & Costa, 2021; Ríos et al., 2024).

In light of the above, this evolving context has generated various divergent opinions, criticisms and practical challenges. However, it has also aroused great interest among academics who have sought to review the tumultuous journey of NFR and provide a comprehensive overview of the literature from different perspectives. Some authors have provided insights, identified gaps, patterns and future directions in NFR through systematic or structured literature reviews (Stefanescu et al., 2021; Korca & Costa, 2021). Others have focused on advancing the field of research using bibliometric analysis tools (Stefanescu, 2021). Furthermore, the previous literature shows that researchers have conducted reviews on specific NFR topics, such as reporting formats (Manes-Rossi et al., 2020), multifaceted dimensions of disclosure quality (Fiandrino et al., 2022), specific types of disclosures (e.g. human resources) (Di Vaio et al., 2020), or the relationships between NFR quality and financial performance (Crous et al., 2022).

While there is no shortage of reviews in this area, few studies have simultaneously examined the topic from the perspective of different parties involved in driving the NFR process (e.g. academics and practitioners). There is a gap in understanding the qualitative aspects (Fiandrino et al., 2022) without empirically testing the interrelationship between them.

However, with recent developments in NFR, the adoption of the new Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), it is particularly important to understand the interactions between the new disclosure requirements and the desired outcome of transparency, and to assess how academics, companies and regulators have contributed to these developments to support further progress.

By addressing the identified limitations, this study aims to enhance the relevance of NFR scholarship, particularly in the emerging field of mandatory corporate sustainability reporting. We achieve this by building on the work of previous researchers who have either similarly approached the topic or provided valuable research avenues for further exploration. Thus, we follow the interplay between academic developments and practitioner perspectives that emerged from the public consultation on Directive 2014/95/EU (NFRD), as also explored by Fiandrino et al. (2022) in the literature analysed. Furthermore, we advance our study by theorising the NFR regulatory process through the exploration of behavioural and cognitive theories, as suggested by Korca & Costa (2021).

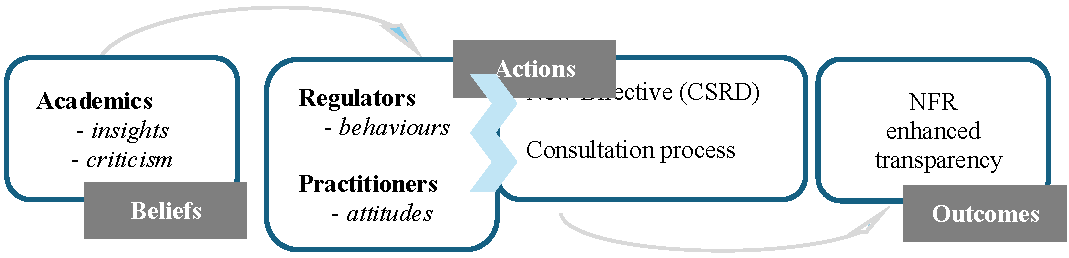

In doing so, we introduce the Belief-Action-Outcome (BAO) framework, developed by Melville (2010), to uniquely conceptualise a research model that embeds the linkages between academic beliefs, regulatory actions, and the desired outcome of the new CSRD based on the literature taxonomy. Since literature undeniably facilitates knowledge and opens new perspectives through insights and critiques, this model aims to emphasise how regulation reflects authorship and public consultation opinions.

Specifically, we set out to answer the following research questions: How did academic insights on NFR qualitative dimensions shape the requirements of new CSRD and its desired outcome of enhancing transparency? Has the business practitioner’s viewpoint strengthened this outcome?

By addressing the research questions raised, this paper contributes to the literature in at least three significant ways. First, it advances knowledge by examining the timely transition process from NFRD to CSRD within a tripartite relationship involving academics, business practitioners and regulators. To the best of our knowledge, this is a novel and noteworthy research topic currently. Second, it represents the first attempt to empirically investigate the links between these three parties and to incorporate them into an original conceptual model based on the BAO framework, following a systematic and integrative literature review. Third, it specifically highlights the interplay between the cognitive, attitudinal and behavioural dimensions of this tripartite relationship, as derived from the literature taxonomy developed. To achieve this, we use partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM), which is suitable for testing complex models that assess relationships between predictors and an outcome (Hair et al., 2019).

We believe that our contributions are relevant to the field as they provide insights into the NFR regulatory framework from both theoretical and empirical perspectives. Moreover, our examination of the connections between the newly introduced disclosure requirements and the goal of enhanced transparency, alongside the roles played by academia, businesses, and regulatory bodies in shaping these requirements, have practical implications that can facilitate ongoing progress. Consequently, the results may prove valuable in guiding decision-makers and assisting businesses in redefining their initiatives to enhance reporting.

The model estimation reveals meaningful connections between the three perspectives as hypothesized. Specifically, academic insights on NFR qualitative dimensions positively shaped the requirements of CSRD and its outcome of enhancing transparency, as well. Additionally, practitioners’ attitudes expressed through public consultation on NFRD strengthened this outcome, as confirmed by the positive moderating effect. Finally, through comprehensive discussions based on the rationalisation of the previously modelled and tested literature taxonomy, our study sheds light on academic contributions to the NFR regulatory process, focusing on areas of new disclosure requirements and their desired transparency outcomes.

The remainder of the paper follows a coherent argumentative structure. Firstly, it explains the design of research conducted (section, 2). Then, it presents a general overview of the NFR evolutionary process and addresses the research questions, grounding them in the BAO framework (section 3). Afterwards, it outlines the protocol for selecting the sampled papers, followed by the model conceptualisation based on literature taxonomy (section 4). The presentation of results begins with a descriptive statistic of the sampled literature and proceeds with model assessment and subsequent discussions (section 5), providing both quantitative and qualitative approaches. Finally, the paper concludes by highlighting its implications and acknowledging its limitations (section 6).

2. Research design

The research, which was intended to go beyond the mere synthesis of existing knowledge on the topic addressed, was appropriately designed to achieve its innovative objective. The main strength of the research design lies in the combination of methodologies from systematic (Tranfield et al., 2003) and integrative literature reviews (Torraco, 2016) to provide a model that should inspire further research. As such, it is in line with the research direction advocated by Korca & Costa (2021), specifically to theorise the NFR regulatory process by exploring behavioural and cognitive models. However, it is not without its weaknesses, as its complexity may make it difficult to follow. To address this issue, Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the relationships between the stages of the research design, the methods and tools used, and the structure of the paper, which are briefly explained below.

The first two stages of the present study follow the organised, transparent and replicable approach of a systematic literature review (Littell et al., 2008).

In planning the review (1st stage), we systematically answered the ‘Why - What - and How - to do?’ questions. Thus, we justified the necessity, purpose and focus of our research. In conducting the review (2nd stage), we identified and selected the relevant literature based on the protocol developed and gathered data for further inquiry.

The last two stages follow the principles of integrative literature review (Snyder, 2019), the most suitable approach for dynamic subjects that may include contradictions or discrepancies. This approach is well-suited to the topic at hand, focusing on NFR, which has recently garnered increased interest and in-depth debates within academia, among practitioners, and regulators. Moreover, it takes the form of synthesis specific to integrative reviews, as we aimed to lay the foundations for new theorising based on conceptual constructs developed by classifying previous research (Torraco, 2016).

Figure 1. Descriptive summary of research progression

Thus, through analysis and synthesis (3rd stage), we created the taxonomy of literature opinions on NFR (based on content analysis) and conceptualised a research model (following the BAO framework). Afterwards, we explained the data analysis process using partial least squares path modelling (PLS-SEM), recommended for non-normal data, small sample sizes and formative indicators estimating complex cause-effect relationships (Hair et al., 2022), which was the case in our dataset. We followed this analysis approach because we aimed to fill a literature gap and move beyond qualitative research. Thus, we advanced into theorising the NFR regulation process by exploring behavioural and cognitive theories, as suggested by Korca & Costa (2021).

The review reporting and dissemination (4th stage) embedded the main findings of our study. It begins with a descriptive analysis of the literature reviewed and its evolutionary trends, following a bibliometric approach. Then, it describes the model assessment using PLS-SEM that provides reliable answers to the research questions addressed, strengthening comprehensive results and discussion. These findings emphasise the linkages between academic beliefs, regulatory actions, and the desired outcome of the new SRD, grounded in the BAO framework.

3. Theoretical background

3.1. Overview of non-financial reporting regulatory process from a tripartite perspective

In recent decades, NFR has undergone a significant regulatory shift, transitioning from the non-coercive Modernisation Directive (2003/51/EC) to the mandatory NFRD (2014/95/EU) and its non-binding guidelines (2017/C215/01), and most recently to the new CSRD (2022/2464/EU).

From a regulatory perspective, the importance of non-financial information was first recognised when the European Commission (EC) outlined an agenda for corporate social responsibility in the Green Paper (EC, 2001). This initiative aimed to promote transparent and accountable business behaviour and sustainable growth (see Table 1).

Table 1. An overview of NFR development in Europe

| Year | EU law | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | EC / Green Paper | Promoting sustainability through voluntary CSR |

| 2003 | EC / Directive, 2003/51 | Promoting non-financial performance indicators |

| 2006 | EC / Directive, 2006/46 | Introducing Corporate governance statement |

| 2011 | EC / Single Market Act | Promoting accountability through transparent NFI |

| 2013 | EC / Directive, 2013/34 | Requiring non-financial and diversity information |

| 2014 | EC / Directive, 2014/95 | Introducing mandatory non-financial statement for large undertakings and groups |

| 2017 | EC / Guidelines C215/01 | Guidelines on non-financial reporting |

| 2022 | EC / Directive, 2022/2464 | Introducing corporate sustainability reporting |

However, such voluntary approaches failed to improve transparency due to their non-coercive nature (FEA, 2016). Over time, international regulators recognised the key weaknesses of voluntary disclosures, which were described as inaccurate, inconsistent, insufficient, unbalanced and not comparable. Recognising that transparency is essential to steer towards a sustainable global economy, they made the disclosure of non-financial information mandatory through Directive 2014/95/EU (EC, 2014).

Furthermore, they supported organisations during the implementation process and encouraged them to report in a comparable, concise and consistent manner by issuing non-binding guidelines (EC, 2017). However, following the public consultation to gather stakeholder feedback after two years of reporting, the EC acknowledged that the NFRD had not significantly improved the quality of disclosure (EC, 2020). Consequently, to strengthen sustainability reporting and better align global approaches with the NFRD while setting a baseline standard (EC, 2022), the new CSRD has recently been published. It aims to ensure coherence between financial and non-financial information and requires companies to disclose reliable, targeted and easily accessible data.

From the practitioners’ perspective, this evolutionary regulatory process emerged as a response to responsible behaviours already in practice at the organisational level. Several surveys have provided evidence of the actions taken by companies over time and their beliefs, which have supported the adoption of NFRs across Europe. For example, a survey conducted by KPMG found that 90% of the world's 250 largest companies disclosed non-financial information as evidence of their responsible behaviour on environmental, social and governance issues (KPMG, 2017). Similarly, a survey by Ernst and Young found that around 68% of investors recognise the usefulness of non-financial reports in making investment decisions, highlighting the importance of such reports to stakeholders (EY, 2017).

Fiandrino et al. (2022) provide further evidence of practitioner feedback from the public consultation on Directive 2014/95/EU (NFRD). The views expressed in this consultation reflect a strong consensus on the need to specify social and environmental issues, in line with the EU Taxonomy on Sustainable Finance. There's also a call for standardised NFR guidelines to take account of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The experts also agree on the lack of a universally accepted definition of materiality and address different interpretations, including "double materiality" and its relationship to assurance. They also advocate the seamless integration of NFI disclosures into mainstream corporate reporting, moving away from separate reporting practices. This shift reflects the broader trend towards holistic corporate reporting, encompassing elements such as strategy, risk management, metrics and targets, while adapting financial reporting for sustainability and enhancing market transparency.

From an academic perspective, the tumultuous journey of instilling NFR has also inspired many scholars who have often addressed this topic and advanced the research stream through empirical evidence and relevant discussions. Broadly speaking, the NFRD has been criticised over time for several reasons: it promoted voluntarism by relying on the 'comply or explain' principle (García-Benau et al., 2022); it created a lack of credibility without an assurance report on accuracy and reliability (La Torre et al., 2018; Venturelli et al., 2019); it did not require a specific model for the non-financial statement, making disclosures incomparable and leading to a chaotic reporting system (Tsagas & Villiers, 2020); it only regulated minimum disclosure requirements (Kinderman, 2020). As a result, it was perceived as inefficient regulation (Szabó & Sorensen, 2017), non-prescriptive in design (Biondi et al., 2020), and far too ambiguous and flexible (Kinderman, 2020). The NFRD has been more rhetoric than reality (La Torre et al., 2018), a "light touch intervention" rather than a strict regulatory framework (Aureli et al., 2019), despite the additional measures taken, such as the accompanying non-binding guidelines (Korca & Costa, 2021). Despite all these limitations gathered from the broad academic debate, the NFRD marked an essential step in improving transparency by formally regulating disclosure and opened a new beginning in the standardisation of sustainability reporting across Europe (Stefanescu, 2022), paving the way for the new CSRD.

Consequently, the above tripartite perspective (regulators, practitioners, academics) emphasises that they have always acted as interrelated parties in this ever-evolving NFR reform, with their decisions being guided by the behaviour and opinions of others. Academics have already suggested that a collaborative approach between businesses and EU governance bodies through structured consultation events could positively influence the adoption of regulations (Korca & Costa, 2021). Against this background, the opportunity arose to enrich the literature by approaching NFR reform from an innovative perspective. The aim is to outline the links between this tripartite relationship by embedding it in an original conceptual model.

3.2. Research conceptualisation and hypotheses

The conceptual setting for the current research is the Belief-Action-Outcome (BAO) framework developed by Melville (2010). It builds on the macro-micro-relations model introduced by Coleman (1986), which incorporates: (a) the beliefs of individuals about a certain situation; (b) corresponding responsive actions of individuals about specific practices and/or processes; and, ultimately, (c) the outcomes achieved.

The BAO framework was initially used in sociology (Coleman, 1994). More recently, it has been adopted in other fields to outline ideas and define constructs for observing the behaviour of individuals in different contexts. For example, it has frequently appeared in empirical studies attempting to manage complex relationships between concepts in organisational and knowledge management, green information technology and digitalisation, environmental sustainability reporting and performance (Bellamy et al., 2020; Ojo et al., 2019). It has even been applied in specific domains, such as the banking industry (Taenja & Ali, 2021) or SMEs (Isensee et al., 2020; Baggia et al., 2019). However, in this wide range of research, only one study developed a novel extension of the BAO framework based on a systematic literature review (Isensee et al., 2020). This study examined the relationship between organisational culture, sustainability and digitalisation in SMEs.

In this context, it laid the foundation for innovation in the traditional literature reviews in the field of NFR (Fiandrino et al., 2022; Stefanescu, 2022; Stefanescu et al., 2021). Consequently, following a systematic and integrative approach, we refined and extended the findings of previous research based on the relationships outlined in the BAO framework.

In our study, beliefs represent the cognitive state of academics regarding transparency in NFR and are shaped by their insights and criticism. These beliefs may intersect with the attitudes of practitioners who have embraced NFR either voluntarily or mandatory, as well as with the behaviours of regulators who have made sustained efforts over time to enhance it. These interconnections have led to specific actions, including the public consultation process launched by EC to revise the NFRD and, ultimately, the enactment of the new CSRD. As a result, all three parties involved in the NFR process may contribute to its desired outcome - enhanced transparency.

Figure 2. Conceptualisation of research model

In this setting, defined by beliefs, actions, and outcomes, and following this logical structure, we developed our conceptualised research model (see Figure 2).

The model's purpose is to systematically organize and integrate previous research, guided by the BAO framework perspective. It aims to empirically assess the hypothesized connections within the tripartite relationship (academics - practitioners - regulators) that have resulted in the new CSRD requirements for enhancing transparency, as outlined in Table 2:

Table 2. Conceptualisation of research model

| Hypotheses | BAO linkage tested / Tripartite relation covered | |

|---|---|---|

| H1: | Academic insights on NFR qualitative dimensions positively shaped the requirements of CSRD | Belief-Action / Academics-Regulators |

| H2: | Academic insights on NFR qualitative dimensions positively shaped the desired outcome of CSRD, leading to enhanced transparency | Belief-Outcome / Academics-Regulators |

| H3: | Practitioners’ attitudes expressed through public consultation on NFRD had a moderating effect on the outcome of CSRD | Action-Outcome / Practitioners-Regulators |

4. Methodology framework

4.1. Literature search and selection

The search strategy relied on eight transparency criteria that define the quality of NFRs (accessibility, clarity, comparability, completeness, consistency, relevance, reliability and timeliness) (Aureli et al., 2019, Stefanescu et al., 2021). The Clarivate Analytics Web of Science (WOS) was queried. We chose it because it is the most prestigious academic literature database (Wang & Waltman, 2016), widely accessible and widely used (Di Vaio et al., 2020) due to the importance and relevance of the publications (Mongeon & Paul-Hus, 2016). Although the Scopus database covers a larger number of journals, their impact is lower, which has kept the WOS database as the preferred choice among researchers and considered as the 'gold standard' for analyses (Harzing & Alakangas, 2016).

The query string applied to the topics of the documents allowed us to retrieve the studies that addressed the quality of disclosure through different types of reporting, in line with Directive 2014/95/EU. The search was specifically limited to peer-reviewed, English-language articles from scientific journals, in order to collect the most valuable findings in the researched area (Mio et al., 2020). The period for this search started in, 2014, which allowed us to analyse trends in the literature from the first formalisation of the NFR (Directive, 2014/95/EU) and the new rules on corporate sustainability reporting (Directive, 2022/2464/EU).

Following the application of these criteria, the titles and abstracts of the selected articles were thoroughly reviewed to ensure their relevance to the research topic and to gain a deeper understanding of the subject, following the methodology outlined by Tranfield et al. (2003). The final sample consisted of 134 academic papers that were highly relevant to the present research.

The detailed research protocol is presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Search protocol

| Criteria | Details |

|---|---|

| Timespan | 2014 -, 2022 |

| Document type | Articles, Review articles, Early access |

| WoS Index | Social Science (SSCI), Emerging Sources (ESCI), Science Expanded (SCI-EXPANDED) |

| Fields | Topic (title, abstract, keywords) |

| Key-terms | (non-financial / sustainability / CSR report*) OR (non-financial / sustainability / CSR disclosure) AND (quality / mandatory / accountability / transparency / accessibility / clarity / comparability / completeness / consistency / relevance / reliability / timeliness) AND (Directive, 2014/95/EU / Non-financial Directive / Non-financial Reporting Directive) |

4.2. Data, measurement and operationalisation

To operationalise our research model, we gathered insights from the selected literature and developed a taxonomy of research perspectives on NFR to assess the interconnections within the tripartite relationship of academics, practitioners, and regulators, as outlined by the BAO framework.

To further develop the literature taxonomy used to operationalise our research model, we proceed as follows:

From the academic viewpoint, we drew from prior accounting literature that focused on transparency in reporting, specifically the works of Stefanescu (2022) and Aureli et al. (2019). These studies examined eight dimensions of disclosure quality, including completeness, relevance, clarity, comparability, consistency, accessibility, timeliness, and reliability. We further deconstructed and evaluated each qualitative dimension based on the criteria provided by Fiandrino et al. (2022).

To capture the perspective of practitioners, we followed the approach outlined by Fiandrino et al. (2022). This involved identifying commonalities and disparities between academic literature and the public consultation process. Consequently, we used these criteria to identify the view of practitioners as approached within the analysed literature.

In terms of the regulatory perspective, we focused on the five key areas of disclosure requirements: scope, content, reporting framework, disclosure format and assurance, as previously studied by Stefanescu (2022). Additionally, we considered the qualitative enhancements defined by regulators through the new CSRD requirements, which aimed to improve transparency by making information more understandable, relevant, representative, verifiable, comparable, and presented in a faithful manner.

To operationalise the research model, we conducted a content analysis of the sampled papers to code information based on the literature taxonomy. This research method is highly flexible and has been widely adopted as a rigorous and systematic approach to identify and summarise trends in the literature in qualitative studies and to measure latent constructs in quantitative research (Gaur & Kumar, 2018). Within the content analysis, we used a dichotomous approach to evaluate each paper from three perspectives: academics, practitioners and regulators. To quantify the information, a score of '1' was assigned for each item that was met, and '0' otherwise. These scores were then used to assess both formative and reflective constructs. This approach allowed us to test our hypotheses using path analysis, as described in section 5.2.

To thoroughly examine the sampled papers, we applied a 'meaning-oriented' content analysis, which takes into account semantic aspects (Krippendorff, 2018). This approach enriched the value of our work by focusing more on the quality and depth of textual interpretation and underlying concepts, rather than simply counting word frequencies. This approach also facilitated the development of the rationalisation of the literature taxonomy (see Appendix) and allowed us to conduct a qualitative analysis of the sampled literature, which is presented as a discussion of the research streams in Section 5.3.

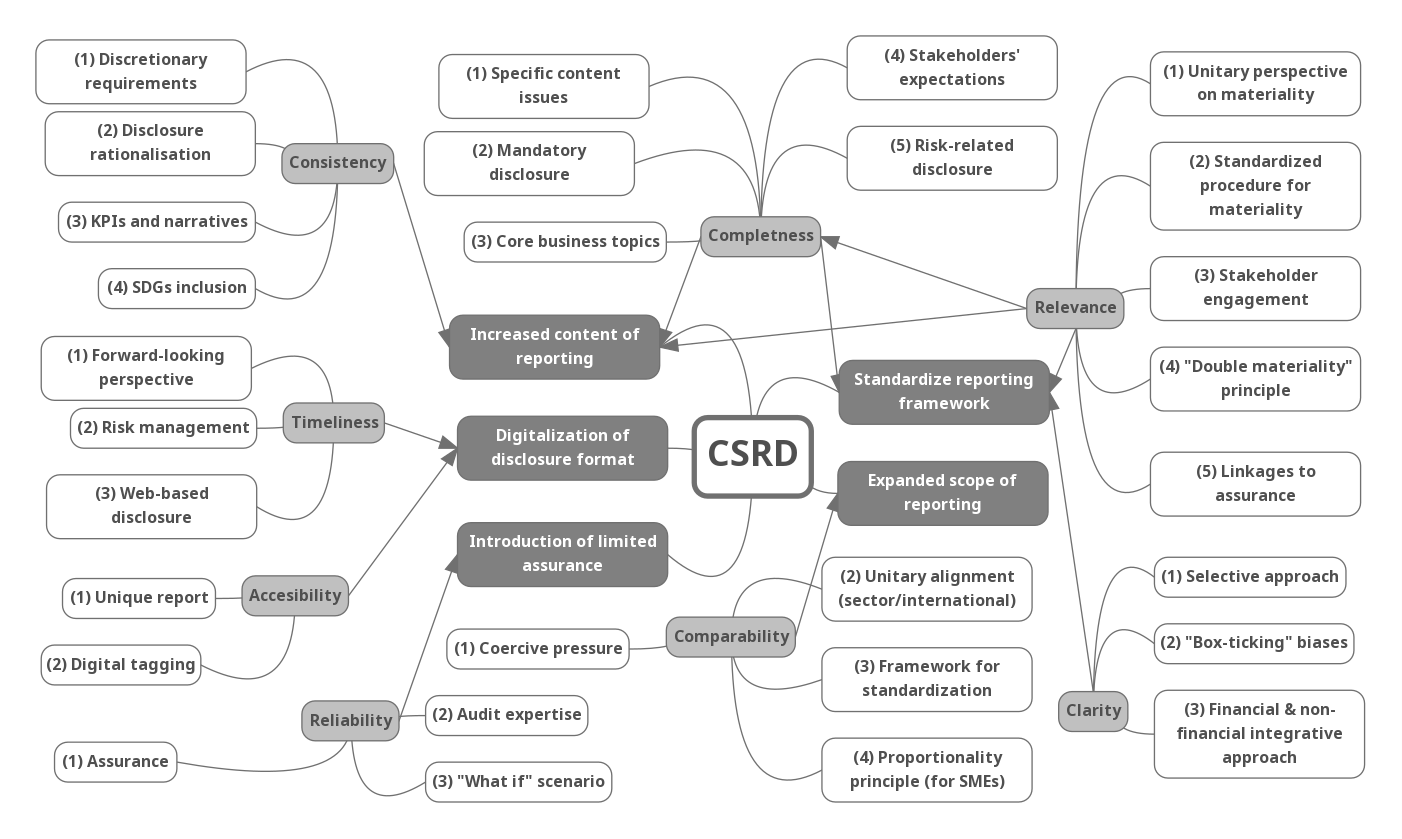

The operationalisation of the conceptualised model is presented in Figure 3, with each construct being explained below.

Figure 3. Operationalisation of research model

CSRDR (Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive Requirements) uses eight formative first-order constructs to capture the literature perspectives (LIT) on each qualitative dimension of non-financial disclosure (completeness, relevance, clarity, comparability, consistency, accessibility, timeliness, and reliability). It aims to illustrate academic beliefs. For this purpose, we drew upon the dashboard of the interplay between the academic and professional debates provided by Fiandrino et al. (2022), as guidance for judging each dimension.

Additionally, CSRDR was operationalised as a reflective second-ordered construct with five items (scope, content, reporting framework, disclosure format and assurance). These measures aim to capture the regulatory actions related to the main areas of CSRD requirements designed to enhance transparency. This approach has previously served as a reference point when analysing NFRD from a similar perspective (Stefanescu, 2022).

CSRDQ (Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive Quality) is modelled as a reflective first-order construct with six items serving as measures of the quality of information disclosed according to the new CSRD. These measures include understandable, relevant, representative, verifiable, comparable, and faithful manner. It aims to reflect the literature’s support in achieving the desired outcome of enhanced transparency by addressing any of these areas.

NFRDPC (Non-Financial Reporting Directive Public Consultation) is operationalised as a single-item variable representing the overall level of commonalities, as defined by Fiandrino et al. (2022), between academic beliefs and the feedback received from professionals through the public consultation on NFRD (see items with *) in the formative measurement model).

4.3. Data analysis process

In this complex context, and given the limitations of certain data analysis techniques (e.g. multiple regression), we decided to use a structural equation modelling (SEM) approach. SEM is a multivariate data analysis technique that allows the simultaneous investigation of multiple associations by simplifying the relationships between variables. It is particularly well suited to exploratory research aimed at predicting a model that explains the causal relationships of the constructs of interest (Hair et al., 2022). This approach was consistent with the aims of our study, as our model is predictive. Its primary aim is to establish a link between academic beliefs (LIT) and new regulatory outcomes (CSRDQ), while also considering the legislative and practitioner actions in between (CSRDR and NFRDPC). Thus, it allowed us to test the hypothesised relationships and was also the most appropriate method to simultaneously assess the mediation-moderation effects of regulatory actions (CSRDR) and practitioners' perspectives (NFRDPC). Specifically, we analysed the connection between LIT and CSRDR (H1), as well as CSRDQ (H2), and explored whether NFRDPC had a moderation effect (H3).

We relied on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) and used SmartPLS statistical software for data analysis and model validation for several compelling reasons.

First, PLS-SEM uses constructs as variables that consist of multiple items (e.g. qualitative dimensions of disclosures in our case). This approach better captures the characteristics of the complex concepts under study, thereby strengthening the robustness of our results and their interpretation. It is therefore highly recommended for explaining and predicting new phenomena, making it ideal for testing and extending a theory (Hair et al., 2022), as is the focus of this study.

Second, it simultaneously estimates causal relationships between all constructs while accounting for measurement error in the structural model (Hair et al., 2022). Therefore, it allowed us to investigate complex relationships between latent variables with different effects (direct and indirect) while analysing their mediation and mediator roles (see Figure 3).

Thirdly, PLS-SEM imposes fewer restrictions compared to other structural equation modelling approaches (e.g. covariance-based SEM (CB-SEM), which requires the fulfilment of certain assumptions). Accordingly, it can be used when there are no assumptions about the data distribution or when there is little theory available, when sample sizes are small and predictive accuracy is paramount. In this context, we considered the PLS-SEM approach to be the most appropriate for our data set (a sample of 134 cases) and the complexity of the model analysed (interrelationships between a large set of constructs; and items used for both explanatory and predictive research).

This technique has already been widely applied, especially in fields such as psychology, sociology, education and marketing, but has been less used in accounting and reporting research (Nitzl & Chin, 2017; Lee et al., 2011), which adds value to the present study.

5. Results, assessment and discussions

5.1. Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics, based on the sample data following a bibliometric approach, provide a general overview of the literature analysed. During the timespan studied (2014-2022), the 134 scientific papers reviewed were published in 59 different journals, with a contribution of, 293 authors representing 32 countries. Table 4 summarises the literature review profile.

Table 4. Literature review profile

| Sample profile | Options | Values |

|---|---|---|

| Document type | Article | 91.79% |

| Early access article | 5.22% | |

| Review article | 2.99% | |

| Authors | Single-authored documents | 4.44% |

| Multi-authored documents | 95.56% | |

| Authors per document | 2.72 | |

| Countries of origin | 32 |

Figure 4 displays the size and growth of the research sample and the trend of topics addressed. The yearly evolution of publication shows a steady ascending tendency, reaching its peak (45 papers) in, 2022. Within the trending topics thematically related to NFR, concepts like ‘quality’, ‘impact’ and ‘determinants’ of the disclosure have gained noticeable relevance (centrality) in recent years, reflecting the worldwide emphasis on enhancing organizational transparency and accountability towards stakeholders.

Figure 4. Evolutionary trends in scientific production thematic topics approached

From an evolutionary perspective, research on this topic began with occasional interest. Its relevance increased over time, with attention remaining constant between, 2020 and, 2021, and then intensifying significantly in the last year. Figure 5 reflects the breadth and intensity of the top authors’ production over time, highlighting their growing contribution to the NFR literature.

Figure 5. Top-authors’ production overtime

Although this research topic is relatively new, as mandated NFR is still in its infancy, there has always been a strong interest in improving its quality. Thus, many scholars have explored its multifaceted dimensions and provided valuable insights to advance knowledge and regulation in this field.

5.2. Model assessment -- quantitative analysis results

To properly evaluate the quality of the path model developed, this study employs the two-stage approach of PLS-SEM assessment: (1) the measurement model (outer model), which specifies the relationship between the observable variables (items) and the theoretical concepts (constructs); (2) the structural model (inner model), representing the underlying causal relationships. Since the model encompasses both formative and reflective constructs, these were separately evaluated as follows (see Table 5):

Table 5. Stages of PLS-SEM analysis

| 1st stage | → | 2nd stage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Formative model | (b) Reflective model | (c) Structural model | |

| - collinearity (VIF) - outer weights / loadings | - internal consistency - convergent validity - discriminant validity | - path coefficients (ꞵ) - coefficient of determination (R2) - effect size (f2) - predictive relevance (Q2) | |

Source: own projection adapted after Hair et al. (2022).

5.2.1. Measurement model assessment

(a) Formative model

Literature perspectives on the eight dimensions of disclosures’ quality are latent constructs with formative indicators expressed as functions of their items (academic beliefs on each qualitative facet). Since these observed variables precede, form, and cause the construct, it was essential to test potential multicollinearity among them by computing the variance inflation factor (VIF). High collinearity (VIF > 5) might result in unstable estimates that would make it difficult to separate the effect of each indicator on the construct (Hair et al., 2019). Furthermore, we needed to test how each formative item contributes to the composite construct to which it belongs. In this vein, we computed the statistical significance and relevance of the outer weights and loadings by running the bootstrapping procedure using the Bias Corrected and Accelerated option (BCa).

Table 6 shows the results of the formative measurement model assessment. Since the maximum VIF value for all indicators (2.981 for const_3) is well below the threshold of 5, collinearity does not reach critical levels in any of the formative constructs and is not an issue for estimating the PLS path model.

Once we checked the significance of the outer weights, we observed the presence of eight non-significant formative indicators due to their varying contributions to shaping a construct. However, removing those items would mean reducing the strength of a composite latent construct, which might have adverse consequences on the content validity of the measurement model (Hair et al., 2022). In this context, we also analysed their outer loadings and finally agreed to keep them all, as they were significant. This decision enabled us to provide the most holistic model that entirely considers the academic opinions on disclosure quality expressed in the sampled papers.

Table 6. Assessments results of the formative measurement model

| Construct | Indicator (item) | Description | Outer weights /loadings*) | t-values | p-values | CIs (Bias corrected) | VIF | Signif. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completeness | comp_1 | Specific content issues*) | 0.450/0.801 | 3.782 | 0.000 | [0.224; 0.690] | 2.013 | Yes |

| comp_2 | Mandatory disclosure | 0.270/0.429 | 2.543 | 0.011 | [0.061; 0.470] | 1.160 | Yes | |

| comp_3 | Core business topics | -0.004/0.723 | 0.025 | 0.980 | [-0.309; 0.323] | 2.453 | No | |

| comp_4 | Stakeholders’ expectations*) | 0.342/0.728 | 3.130 | 0.002 | [0.116; 0.545] | 1.849 | Yes | |

| comp_5 | Risk-related disclosures | 0.369/0.753 | 3.633 | 0.000 | [0.169; 0.571] | 1.475 | Yes | |

| Relevance | relv_1 | Unitary perspective on materiality*) | 0.322/0.818 | 2.606 | 0.009 | [0.095; 0.575] | 2.012 | Yes |

| relv_2 | Standardised procedure for materiality*) | 0.279/0.790 | 2.197 | 0.028 | [0.022; 0.518] | 1.874 | Yes | |

| relv_3 | Stakeholder engagement | 0.468/0.893 | 3.247 | 0.001 | [0.205; 0.782] | 2.553 | Yes | |

| relv_4 | ‘Double materiality’ principle*) | 0.006/0.365 | 0.057 | 0.955 | [-0.185; 0.219] | 1.269 | No | |

| relv_5 | Linkages to assurance*) | 0.226/0.424 | 2.317 | 0.021 | [0.042; 0.433] | 1.167 | Yes | |

| Clarity | clar_1 | Selective approach | 0.749/0.928 | 11.397 | 0.000 | [0.619; 0.876] | 1.420 | Yes |

| clar_2 | ‘Box-ticking’ biases | 0.416/0.757 | 6.592 | 0.000 | [0.293; 0.539] | 1.273 | Yes | |

| clar_3 | Financial and non-financial information integrative approach*) | -0.039/0.281 | 0.527 | 0.598 | [-0.202; 0.090] | 1.139 | No | |

| Comparability | compb_1 | Coercive pressure | 0.408/0.912 | 2.625 | 0.009 | [0.116; 0.724] | 2.590 | Yes |

| compb_2 | Unitary alignment (sector/international) *) | 0.364/0.895 | 2.563 | 0.010 | [0.091; 0.645] | 2.482 | Yes | |

| compb_3 | Framework for standardisation*) | 0.116/0.536 | 1.217 | 0.224 | [-0.074; 0.305] | 1.268 | No | |

| compb_4 | Proportionality principle (for SMEs) *) | 0.301/0.796 | 2.550 | 0.011 | [0.071; 0.517] | 1.687 | Yes | |

| Consistency | const_1 | Discretionary requirements | 0.516/0.935 | 3.051 | 0.002 | [0.192; 0.856] | 2.636 | Yes |

| const_2 | Disclosure rationalisation | 0.204/0.862 | 1.021 | 0.308 | [-0.165; 0.622] | 2.981 | No | |

| const_3 | KPIs and narratives*) | 0.380/0.881 | 2.086 | 0.037 | [0.027; 0.754] | 2.248 | Yes | |

| const_4 | SDGs inclusion*) | 0.013/0.529 | 0.094 | 0.925 | [-0.279; 0.283] | 1.515 | No | |

| Accessibility | acces_1 | Unique report | 0.595/0.919 | 2.914 | 0.004 | [0.174; 0.964] | 1.678 | Yes |

| acces_2 | Digital tagging*) | 0.510/0.888 | 2.355 | 0.019 | [0.053; 0.887] | 1.678 | Yes | |

| Timeliness | time_1 | Forward-looking perspective*) | 0.651/0.952 | 3.683 | 0.000 | [0.276; 0.955] | 2.141 | Yes |

| time_2 | Risk management | 0.434/0.890 | 2.297 | 0.022 | [0.090; 0.821] | 2.025 | Yes | |

| time_3 | Web-based disclosure*) | -0.016/0.412 | 0.127 | 0.899 | [-0.274; 0.22] | 1.223 | No | |

| Reliability | relb_1 | Assurance*) | 0.306/0.879 | 1.853 | 0.065 | [-0.026; 0.623] | 2.448 | No |

| relb_2 | Audit expertise | 0.644/0.943 | 4.262 | 0.000 | [0.357; 0.954] | 2.204 | Yes | |

| relb_3 | ‘What if’ scenario*) | 0.217/0.568 | 1.951 | 0.051 | [0.09; 0.447] | 1.249 | Yes |

*) all outer loadings P values > 0.05

(b) Reflective model

Academic insights and criticism on NFR expressed over time have significantly influenced the development of corporate sustainability reporting. The new regulatory requirements (CSRDR) and their aim to increase transparency (CSRDQ) are latent constructs with reflective indicators. These encompass the effects of their underlying constructs, specifically the primary areas of CSRD changes (e.g. scope, content) and the qualitative improvements achieved (e.g. understandability, relevance).

Initially, our focus was on assessing three key aspects:

(1) convergent validity. This measures the degree to which each item strongly correlates with its assumed construct.

(2) internal consistency. This checks whether the indicators genuinely measure the constructs.

(3) discriminant validity. This ensures that a reflective construct maintains robust relationships with its items.

The results of the estimation of our reflective measurement model are presented in Table 7.

Table 7. Assessments results of the reflective measurement model

| Construct | Indicator (item) | (1) Convergent validity | (2) Internal consistency | (3) Discriminant validity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loadings | IR3) | AVE4) | CR1) | α2) | HTMT5) | ||

| CSRDR | Scope | 0.778 | 0.605 | 0.582 | 0.874 | 0.820 | supported |

| Content | 0.736 | 0.541 | |||||

| Reporting framework | 0.845 | 0.714 | |||||

| Disclosure format | 0.679 | 0.461 | |||||

| Assurance | 0.768 | 0.589 | |||||

| CSRDQ | Understandable | 0.684 | 0.468 | 0.576 | 0.890 | 0.852 | |

| Relevant | 0.810 | 0.656 | |||||

| Representative | 0.754 | 0.569 | |||||

| Verifiable | 0.762 | 0.581 | |||||

| Comparable | 0.865 | 0.748 | |||||

| Faithful | 0.660 | 0.436 | |||||

1) CR: composite reliability; 2) α: Cronbach’s Alpha; 3) IR: indicator reliability; 4) AVE: average variance extracted; 5) HTMT: Heterotrait-monotrait criterion (confidence intervals does not include 1)

In the following, we briefly address and justify each evaluation criterion, along with the reported results:

Since indicators of a reflective construct are regarded as alternative approaches to measuring the same construct, high outer loadings are desirable. These loadings reflect that the associated indicators share a significant portion of what is captured by the construct, a concept known as indicator reliability (IR). Additionally, the average variance extracted (AVE) indicates how positively an item correlates with the alternative items of the same construct. The results of all these measurements exceed the required threshold of 0.5 (Sarstedt et al., 2021), demonstrating the appropriate convergent validity of our reflective model.

Since internal consistency typically falls between Cronbach’s alpha \((\alpha)\) (the lower bound) and the composite reliability (CR) (the upper bound) (Hair et al., 2019), we considered both measures to assess it. Their values exceeded the recommended cut-offs of 0.7 (Sarstedt et al., 2021).

Since three different measurements might be used to analyse discriminant validity, we based on prior evidence to choose the most suitable one for our model. Recent research that critically examined the performance of cross-loadings and the Fornell-Larcker criterion has found that neither approach reliably detects discriminant validity issues (Henseler et al., 2016), especially when indicator loadings of the constructs under consideration differ only slightly. For this reason, we ultimately used the Heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT). This approach allowed us to estimate whether there would be a meaningful correlation between two constructs if these were perfectly and reliably measured. Table 8 and Table 9 show the results of the discriminant validity tests.

Table 8. Discriminant validity tests’ results (Fornell–Larcker criterion)

| Fornell–Larcker criterion*) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| CSRDR | CSRDQ | NFRDPC | |

| CSRDR | 0.763 | ||

| CSRDQ | 0.759 | 0.802 | |

| NFRDPC | 0.713 | 0.693 | 1.000 |

*) The square root of AVE’s are shown diagonally in bold.

Table 9. Discriminant validity tests’ results (HTMT ratio)

| HTMT ratio*) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| CSRDQ | CSRDR | CSRDR * NFRDPC | |

| CSRDR | 0.844 | ||

| CSRDR * NFRDPC | 0.342 | 0.063 | |

| NFRDPC | 0.741 | 0.776 | 0.143 |

*) confidence intervals does not include 1

In the case of the Fornell-Larcker criterion, the square roots of AVE (the diagonal elements) should be significantly higher than the variance shared between the construct and other latent variables (off-diagonal values). Our results reveal that this condition is satisfied for each reflective construct.

To address the reliability limitation, we have also used the HTMT ratio as an upper boundary estimate of the correlation. Its value should be lower than 0.85 to discriminate between two constructs (Henseler et al., 2016). Our results show that all variables achieve discriminant validity following the HTMT approach. Furthermore, the bootstrap confidence interval results also clearly support this, as they do not include 1 (Franke & Sarstedt, 2019).

In conclusion, all the above outcomes emphasize that our measurement model is reliable and valid and can be used further to assess the structural model.

5.2.2. Structural model assessment

(a) Model robustness

Having confirmed the adequacy of the measurement scales for the constructs included in the path model, we proceeded to the final stage of the analysis by testing its ability to foretell the assumptions. The assessment aimed to examine the model’s predictive capability and the relationships between the constructs. This assessment is based on the results reached from the model estimation, as well as the bootstrapping and blindfolding procedures.

First, we checked the structural model for collinearity issues. Since all VIF values were clearly below the acceptable standard threshold of 5 (Hair et al., 2022), collinearity among the constructs was not a critical concern.

Subsequently, we used the main criteria to assess the quality and robustness of the structural model in terms of predictive power (R2 value) and predictive relevance (Q2). Additionally, we examined the relative impact (f2 and q2 effect size) to evaluate whether an omitted latent variable significantly influenced the endogenous constructs.

The R2 value of the endogenous constructs (ranging from 0.509 for NFRDPC to 0.727 for CSRDQ) demonstrates the high predictive accuracy of our model. Since this value typically ranges between 0 and 1 (higher values indicating a greater explanatory power), our results (all above the threshold of 0.5) suggest that the endogenous constructs explain a substantial amount of the variance.

Similarly, our model exhibits satisfactory predictive relevance for all the endogenous constructs, as indicated by the Q2 values, which are around the medium threshold of 0.25 and the large threshold of 0.5. This is revealed by the cross-validated redundancy approach of the blindfolding procedure (0.391 for CSRDQ and 0.524 for CSRDR).

The effect size (f2), which measures the influence of a predictor construct on an endogenous latent variable, indicates that literature insights (LIT) on CSRDQ are highly mediated (0.820), whereas the practitioners’ voice (NFRDPC) had only a low moderating effect (0.197), both at a 5% significance level.

Finally, we examined the assumed relationships through the path coefficients (see Table 10) by analysing their sign, magnitude, and significance (Hair et al., 2019). Moreover, as bootstrap confidence intervals provide further information on the stability of the model estimates (Streukens & Leroi-Werelds, 2016), we also reported the results of the Bias-Corrected and Accelerated (BCa) bootstrapping approach using 5000 bootstraps resamples. Additionally, it allowed us to estimate the mediation and moderation effects (Preacher & Hayes, 2008).

(b) Hypothesis testing and path analysis results

Firstly, in terms of direct effects, path coefficient values provide empirical support for six of the eight qualitative dimensions covered by the literature (LIT) at a 1% significance level. The results reveal that academic insights had a positive and meaningful effect (\(\beta\) ranging from 0.128 for ‘Reliability’ to 0.313 for ‘Clarity’) on the new regulatory requirements (CSRDR). However, academic opinions on ‘Completeness’ and ‘Accessibility’ were the least influential and statistically insignificant (p = 0.481, respectively 0.601, and the confidence intervals of the bootstrapping contain the zero value). Overall, due to the direction, strength and significance of the path coefficients, hypothesis H1 was accepted. In other words, academic insights on NFR qualitative dimensions positively shaped the requirements of CSRD.

Subsequently, indirect effects were analysed to assess the impact of academic insights, mediated by new regulation requirements (H2), and the moderator role of the practitioners’ attitudes (H2) on the desired outcome - enhanced transparency.

To check the mediation in the ‘LIT \(\to\) CSRDR \(\to\) CSRDQ’ relationship, variances accounted for (VAF) were calculated to determine whether the size of the indirect effect on the total effect reveals a partial or full mediation, using the cut-off of 0.8 (Hair et al., 2019). The results confirm a positive and significantly mediated relationship (\(\beta\) = 0.686, and the confidence interval does not include zero value; VAF = 96.21%). Since both direct and indirect effects are significant, and the proportion mediated is prominent, a full mediation is suggested, supporting hypothesis H2. Thus, academic insights on NFR qualitative dimensions positively shaped the desired outcome of CSRD - enhanced transparency.

Table 10. Assessments results of the structural model

| Hypotheses / Relationships | ꞵ coeff. | t-values | p-values | CIs (Bias corrected) | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (H1): LIT → CSRDR | |||||

| (1) Completeness | 0.028 | 0.705 | 0.481 | [-0.060; 0.095] | No |

| (2) Relevance | 0.139 | 3.231 | 0.001 | [0.056; 0.225] | Yes |

| (3) Clarity | 0.313 | 6.976 | 0.000 | [0.234; 0.412] | Yes |

| (4) Comparability | 0.288 | 7.369 | 0.000 | [0.222; 0.379] | Yes |

| (5) Consistency | 0.148 | 4.293 | 0.000 | [0.091; 0.225] | Yes |

| (6) Accessibility | 0.019 | 0.523 | 0.601 | [-0.061; 0.085] | No |

| (7) Timeliness | 0.190 | 4.136 | 0.000 | [0.109; 0.290] | Yes |

| (8) Reliability | 0.128 | 2.853 | 0.004 | [0.044; 0.216] | Yes |

| (H2): CSRDR → CSRDQ | 0.713 | 12.178 | 0.000 | [0.582; 0.812] | Yes |

| LIT → CSRDR → CSRDQ*) | 0.686 | 7.145 | 0.000 | [0.471; 0.852] | Yes |

| (H3): CSRDR*NFRDPC → CSRDQ**) | 0.216 | 5.113 | 0.000 | [0.132; 0.298] | Yes |

*)Mediating effect **)Moderating effect

Finally, we deemed it appropriate to examine the sampled papers from the perspective of practitioners’ attitudes and assess their ability to strengthen, weaken, or reverse the impact on the enhanced transparency by including the moderation effect (‘CSRDR*NFRDPC \(\to\)CSRDQ’). The results provide empirical support at a 1% significance level and reveal a positive and meaningful influence of the moderation’s interaction term (\(\beta\) = 0.216, and the confidence interval does not include zero value). Thus, hypothesis H3 was accepted. Hence, practitioners’ attitudes expressed through public consultation on NFRD had a moderating effect on the outcome of CSRD.

5.3. Discussions -- qualitative analysis results

Relying on the interrelations confirmed through the research model assessment, as well as the content analysis performed, we seek to further discuss the linkages within the tripartite relationship. The thematic map outlined based on the literature taxonomy tested through our model (see Appendix) has an all-encompassing purpose and functions as a visual interpretation of a flow of connections from the edges to its centre point. It emphasizes the major directions of how academic and business insights on each qualitative dimension of NFR contribute to enhanced requirements of CSRD.

Accordingly, we have delineated the subsequent research streams, each progressively discussed by outlining the new advances in regulation, acknowledging practitioners’ support, and providing in-depth academic evidence.

(a) Expanded scope of reporting to ensure higher comparability

The CSRD reinforced the scope of undertakings concerned, including all listed companies on EU-regulated markets (except micro-entities), large companies, insurance, and credit institutions. It is estimated to cover around 50.000 undertakings compared to the current 11.600. Additionally, SMEs are subject to voluntary reporting but under simplified requirements and a deferred timeline (EC, 2022).

These changes came in response to strong support from business respondents (more than 70%) who advocated for mandatory international alignment based on regional and sectoral approaches. This resulted in specific requirements for certain organisations, such as SMEs (EC, 2020).

The academic beliefs gathered consensus with attitudes expressed through the consultation process. Scholars concluded that there was a strong need to strengthen NFR harmonisation. In the current mandatory context, companies increased disclosure for compliance with the law, driven by what is known as coercive isomorphism (García-Sánchez et al., 2022; Veltri et al., 2020; Dumay et al., 2019) or as a result of the institutionalisation process (Lombardi et al., 2022; Esteban-Arrea & Garcia-Torea, 2022). Moreover, usable benchmarks for comparisons appeared to be effective within companies’ sectors (García-Benau et al., 2022; Raucci & Tarquinio, 2020), indicating a continuous effort for improvement and active support.

(b) Increased content of reporting to enhance completeness and consistency

The CSRD’s new prerequisites encompass both inwards-outwards and forwards-backwards oriented reporting areas, involving a broad range of sustainability-related information. These requirements imposed more detailed information about strategy and business models, sustainability targets, principal risks and indicators (KPI), governance processes, and risk management compared to the previous regulations (EC, 2022).

In this context, business consultations provided clear support for extending non-financial information categories and implementing a taxonomy structure, along with other EU disclosure rules for specific content (EC, 2020).

This improvement, fully embraced by the literature, occurred as a natural progression on the evolutionary path from voluntary to mandatory disclosure (Brejer & Orij, 2022; Nicolo et al., 2020). This transition has been valued over time for various reasons, including its potential to boost performance (Cupertino et al., 2022; Agostini et al., 2022; Loprevite et al., 2020), strengthen the resilience of the banking sector during financial turmoil (Chiaramonte et al., 2022), or increase analyst forecasts (Ferrer et al., 2020).

Likewise, stakeholders’ expectations deepened over time, leading them to seek more trustworthy information. Consequently, additional disclosures on specific content issues were considered in their decision-making processes (Mio et al., 2020; Mittelbach-Hörmanseder & Rammerstorfer, 2021). Notable among these are risk-related information to support decisions based on risky scenarios (De Luca et al., 2020; Veltri et al., 2020; Bernardi & Stark, 2018), anti-corruption actions (Carillo et al., 2019; Dumay et al., 2019); human rights initiatives (Matuszak & Rozanska, 2021; Di Vaio et al., 2020; Buhmann, 2018; Peršić & Lahorka, 2018); due diligence disclosures (Korca et al., 2021; Buhmann, 2017).

Furthermore, the evidence reveals a strong desire to integrate SDGs disclosures (Lashitew, 2021; Garcia-Torea et al. 2019; Di Vaio et al., 2020; Gazzola et al., 2020), not only to enhance NFR quality but also to signal a commitment to sustainable development in a competitive environment (Pizzi et al., 2022; Pizzi et al., 2021).

All of these factors have intensified the need to formalize specific guidelines on topics related to the core business, such as strategy and business models (Di Tullio et al., 2020; Arif et al., 2022), sustainability targets (Fiandrino & Tonelli, 2021), risk assessments and key performance indicators (Venturelli et al., 2019; Zarzycka & Krasodomska, 2022; Arif et al., 2022; Santamaria et al., 2021; Raucci & Tarquinio, 2020). A comprehensive set of topics and indicators for disclosure could facilitate stakeholder decision-making (Zarzycka & Krasodomska, 2022; Stefanescu, 2022) if accompanied by guidelines about ‘how to make it’ and ‘how to use it’ for both preparers and users (Simoni et al., 2022).

(c) Standardize reporting framework to improve clarity, consistency and relevance

The new CSRD clarifies the purpose of reporting from both outside-in and inside-out perspectives, thereby removing any ambiguity surrounding the “double materiality” principle. Consequently, companies are now required to disclose adequate information that reflects both the inward impacts (sustainability risks and opportunities affecting their financial value) and outward effects (societal and environmental). To support this initiative, the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) is developing further sets of mandatory sustainability reporting standards aligned with other EU legislation. The adoption of these standards will follow the principle of proportionality, which means that listed SMEs will apply simpler standards (EC, 2022).

The business environment has shown strong support for these legislative advances. Most respondents in the public consultations believed that companies should be required to disclose their materiality assessment process (75%) and called for the establishment of a common standard for reporting (82%), as well as simplified standards for SMEs (74%) (EC, 2020).

The literature has consistently revealed a global uncertainty about which information is deemed relevant and worthy of specific attention due to the ambiguous way of defining the idea of materiality (Kinderman, 2020). The vagueness of this concept (Aureli et al., 2019) either resulted in the discretion or overabundance of information disclosed (Tarquinio et al., 2020). In turn, it caused uncertainties surrounding the utility of information (Tsagas & Villiers, 2020) jeopardising its consistency over time (Raucci & Tarquini, 2020).

As a result, scholars have continuously recommended stricter guidance (Aureli et al., 2020; Tarquinio et al., 2020) to enhance clarity and remove the biases produced in reporting by the “cherry-picking” approach (Raucci & Tarquinio, 2020; Kristofík et al., 2016) or “box-ticking mentality” (Ahern, 2016). Such guidance should bridge the gaps between coexisting frameworks, such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) framework or integrated reporting (<IR>), while heavily relying on the expertise of best voluntary practice in sustainability reporting standards (Brejer & Orij, 2022; Ottenstein et al., 2022; Venturelli et al., 2019; Raimo et al., 2022).

In addition, materiality is often linked with stakeholder engagement and sustainability governance (Cosma et al., 2021; Mazzotta et al., 2020). Hence, the literature encourages an integrative perspective on reporting, management and decision-making process (Schröder, 2022). This perspective may encompass disclosures of financial and non-financial information, oriented toward both the company’s value creation and environmental preservation (Lombardi et al., 2022; Villiers, 2022; Panfilo & Krasodomska, 2022).

All these opinions have ultimately led to the “double-materiality” principle. Academics not only offered strong support for the rationalisation of information disclosed (Tarquinio et al., 2020) but also advocated for standardised NFR after analysing the myriad of market-driven frameworks (De Micco et al., 2021; Biondi et al., 2020). While the “minimum harmonisation” introduced by the NFRD allowed for a variety of voluntary frameworks and standards (Aureli et al., 2020), it unfortunately left too much freedom for concerned entities (Ahern, 2016) and raised questions about achieving the expected impact (La Torre et al., 2018; Szabó & Sorensen, 2017). In this context, a harmonised standard for reporting with a simplified version for SMEs has finally been considered the best solution (Fiandrino et al., 2022).

(d) Digitalisation of disclosure format to enhance accessibility and timeliness

The new CSRD mandates that companies disclose all information, both financial and non-financial, through the management report using a single electronic reporting format. Additionally, sustainability information must be “tagged” in accordance with a digital taxonomy, ensuring its availability in the upcoming European Single Access Point (ESAP) database (EC, 2022).

The use of technology was strongly advocated during the NFRD consultation process to enhance the utility of information through digital solutions (e.g. tagging of non-financial information and the availability of a single access point) (65%), as well as to provide a comprehensive view of information disclosure (55%) (EC, 2020).

The literature recognizes the benefits of various media supports for diffusing information on time, thus striking transparency (Stefanescu, 2022). In the era of Big Data, where digitalisation and technological advances offer better communication scholars encouraged the use of technology to harmonise taxonomies (e.g. ESG, XBRL reporting) (Faccia et al., 2021; Habermann, 2021) and standardise the format of disclosure while addressing the issue of machine readability (Ottenstein et al., 2022). Also, they acknowledged the relevance of integrating digital media with other communication channels (e.g. corporate reporting, annual meetings, press releases, websites and other internet channels) for diffusing non-financial information on time to be part of the stakeholders’ decision-making process (Aureli et al., 2020).

In addition, authors proposed making non-financial information publicly available on the organisations’ websites and cross-referenced in the management report (Aureli et al., 2020; Matuszak & Rozanska, 2021), encouraging a relational connectivity approach to enhance corporate responsibility (Masiero et al., 2020). They suggested as well that NFR should leave behind the ex-post accountability and move on to a future-oriented perspective focusing on forward-looking sustainability data and a risk management approach that favours a green-washing behaviour (Fiechter et al., 2022; Leopizzi et al., 2020; Caputo et al., 2021; Fiandrino et al., 2022; Cosma et al., 2022).

(e) Introduction of limited assurance to increase reliability and accuracy

The new CSRD enacts a general EU-wide audit requirement for the first time following a progressive approach. It starts with ‘limited’ assurance, given by an independent services provider other than the statutory auditor. Further, it allows the chance for a ‘reasonable’ assurance to become mandatory once the EU reporting standards are introduced (EC, 2022).

This improvement, which resulted in stricter audit requirements, was strongly supported by most participants in the NFRD consultation process (67%) (EC, 2020). Hence, it came as a necessary precondition of non-financial information decision-usefulness that relies on the existence and robustness of external assurance.

Similarly, literature often approached this issue leading to the unitary opinion that the lack of assurance process might jeopardise the credibility of reporting (Fiandrino et al., 2022; Venturelli et al., 2019), thus being a weakness for the company (Buhmann, 2018; Ahern, 2016). Until now, assurance itself was constrained by the lack of NFR standardisation, being limited to ‘formal checks’ of information disclosed (Krasodomska et al., 2020; La Torre et al., 2018). Therefore, requiring independent verification was premature (Ahern, 2016), even though it was widely accepted as foremost for increasing trust among stakeholders (Schröder, 2022; Gillet-Monjarret, 2022; Santamaria et al., 2021; Mio et al., 2020). However, scholars always pleaded for mandating external assurance and enhancing the professionalism of human capital implied (García-Sánchez et al., 2022; Krasodomska et al., 2021).

In conclusion, regulatory bodies’ efforts to strengthen and standardise communication on sustainability-related disclosures finally made NFR enter a new area marked by the CSRD. Unsurprisingly, academic perspectives played an essential role in shaping the entire regulatory process. Their permanent efforts toward analysing NFR and providing valuable insight and criticisms contributed to enhancing the disclosure quality by transforming the reporting system and creating a consistent and comparable baseline. Practitioners’ attitudes had as well the ability to strengthen this entire process of aligning NFR requirements.

6. Conclusions

In recent years, the global community has made significant efforts to strengthen the pathways to sustainable development in a more transparent and accountable business world. Regulators have taken strategic action to improve the quality of reporting, aiming to increase comparability, reliability and relevance to stakeholders beyond the financial statements. Practitioners have drawn on the experience of NFRs over the years as they have moved from voluntary initiatives to mandatory rules, and have used their expertise to support further developments. Academics have often explored the links between accountability, transparency and reporting, providing valuable insights and criticisms for future improvements. As a result, all three parties have played an active role in improving the NFR, ultimately leading to the new CSRD, which is the first milestone in the long journey towards standardised sustainability reporting.

Against this background, we were able to review the current literature on this dynamic topic and explore the research pathways that have led to recent developments in NFR regulation from an innovative perspective. Unlike previous studies that aim to provide a holistic understanding of the NFR literature, this paper seeks to enhance the scholarship by thoroughly examining the links between academics, business practitioners and regulators. Our aim is to provide an empirical analysis of the relationships between the three parties using our literature taxonomy. To achieve our objective, we drew on the work of Fiandrino et al. (2022) and conceptualised a research model based on the BAO framework. We then assessed the model using PLS-SEM modelling and discussed the linkages within the tripartite relationship.

The results indicate that academics played a significant role in enhancing non-financial information transparency during the NFR regulatory process. The model’s estimation confirms the interrelation between the cognitive, attitudinal, and behavioural dimensions of the tripartite relationship involving academics, practitioners and regulators, as envisioned by the BAO framework.

These findings provide empirical evidence on the insights, criticisms and recommendations of academics regarding disclosure quality across the eight dimensions. Their opinions, often in line with those of the business world, helped improved reporting requirements, as mandated by the new CSRD, thereby enhancing transparency. Therefore, our model sheds light on the invaluable contributions of academia, fostering a sense of trust for further progress.

Therefore, all the results mentioned above have practical and theoretical implications. These findings could be useful to policy-makers, catalyzing understanding of the connections between scientific and real-world evidence and providing valuable support for advancements in regulations, thereby fostering a sense of trust. In addition, these findings can guide organisations seeking to move towards a virtuous circle of value creation and meaningful communication. In this context, organisations should recognise that, in addition to improving the future viability of the business and managing its impact on society and the environment more responsibly, it is desirable to report on sustainability issues in a standardised way. Such reporting increases transparency, strengthens the reliability of information and can serve as a valuable incentive in the decision-making process, ultimately leading to better overall performance. Finally, these findings are also relevant for academics interested in further challenging debates on sustainability reporting.

While our study offers novel insights, it is not without limitations, which consequently provides avenues for future research. First, our results must be treated with caution due to the search protocol and the subjectivity of interpretation. The literature analysed was limited to WoS-indexed papers because we wanted to ensure greater accuracy and the highest quality standards for the research review. However, we may have excluded relevant publications on the topic as our dataset did not include proceedings, books and chapters, or other databases such as Scopus or Google Scholar. We are also aware that by relying solely on WOS-listed journals, we may have overlooked important papers that, despite not having a high impact factor, may have added value to this research.

Secondly, since we analysed the sensitive topic of NFR and its qualitative dimensions from three perspectives, we had to rely on our professional judgment for a unifying approach to understanding the continuous improvements and the derived interconnections. However, the analysis could potentially be further developed in specific directions. Therefore, we recommend future research avenues that could be addressed, including: (1) a systematic comparison between the two directives that shaped the path of NFR since it became mandatory, focusing on the main changes (e.g. objective, minimum content, the perspective taken, time horizon approached, linkages required, assurance provider); (2) a comprehensive evolutionary analysis of specific concepts included in the literature taxonomy we created that have undergone developments over time (e.g. materiality principle, assurance process); (3) an in-depth analysis of the benefits of the upcoming transformations of the reporting processes, systems and formats, as well as the efforts associated with meeting the increased requirements set by the new CSRD.

Appendix

Appendix. A rationalisation of literature taxonomy on NFR