Management and accounts of the disentailment process in Seville Cathedral (19th century): the sale of estates

ABSTRACT

Ecclesiastical disentailment has traditionally been associated with seizing real estate owned by "dead hands" for immediate sale. The administrative and accounting documentation of the Cathedral Chapter of Seville shows how it was forced to dispose of numerous properties in two phases during the 19th century. This was not carried out through confiscation but through orderly sales organised by the ecclesiastical institution itself, which is not mentioned in the historical-economic literature. This study analyses these alienations, their causes, procedures and consequences, as well as the financial problems the Cathedral Chapter of Seville faced, the application for numerous loans and the sale of real estate. The sales process, in our opinion, was serious, transparent and professional.

Keywords: Confiscation; Cathedral of Seville; 19th century; Disposal of properties; Management system.

JEL classification: N93; M40.

Gestión y cuentas del proceso de desamortización en la catedral de Sevilla (siglo XIX): la venta de fincas

RESUMEN

Tradicionalmente se ha asimilado desamortización eclesiástica con el proceso de incautación de bienes inmuebles en propiedad de las “manos muertas” para su inmediata venta. La documentación administrativa y contable del Cabildo Catedral de Sevilla muestra como en dos fases del siglo XIX se vio obligada a desprenderse de numerosos inmuebles, no mediante la confiscación, sino mediante un ordenado procedimiento de venta realizada por la propia institución eclesiástica, aspecto no mencionado por la literatura histórico-económica. El presente estudio analiza esas enajenaciones, sus causas, procedimiento y consecuencias. Se analizan los problemas financieros del Cabildo Catedral de Sevilla, la solicitud de numerosos créditos y la venta de inmuebles. El proceso de venta, en nuestra opinión, fue bastante serio, transparente y profesional.

Palabras clave: Desamortización; Catedral de Sevilla; Siglo XIX; Enajenación de fincas; Sistema de gestión.

Códigos JEL: N93; M40.

1. Introduction

Numerous studies have been carried out to date on the successive ecclesiastical disentailments ordered by the Crown during the contemporary Spanish period. These studies have taken two approaches: some, as we shall see below, have attempted to offer global visions of State disentailment processes. However, local studies that attempt to inventory an institution’s or groups of institutions’ assets predominate. In all of them, "disentailment" is synonymous with property seizure. As we shall see, the documentation preserved in the Cathedral Chapter of Seville for the first half of the 19th century shows the legal, economic and accounting aspects of the procedures for disposing of numerous urban and rural properties.

Hence, the main objective of this paper is to study the impact of the disentailment measures on the rich Cathedral Chapter of Seville and to analyse the impact of specific special contributions. To this end, the accounting documentation used during the entire process will be examined in detail: appraisals, offers, sales and the rendering of accounts to civil authorities.

In contrast to the disentailment widely studied in the historical literature, which consisted of the Crown seizing the goods, disposing of them and keeping the proceeds of the sale, we have found two completely different situations:

a) The Cathedral Chapter was obliged to sell a series of properties, but it was entrusted with the management of the process and had to hand over the money obtained from the sale.

b) Exceptional state taxes of enormous amounts were demanded. This led to the ecclesiastical institution falling into debt and, subsequently, being forced to sell properties to repay their loans.

We believe that our study is novel not only because it reveals different procedures for mass property sales, but also because it uses accounting documentation as an enlightening way (Hernández, 2010) to study this economic reality.

Furthermore, as Jorge Tua Pereda indicates in the prologue to the book by Hernández (2013) "Aproximación al estudio del pensamiento contable español", the purpose or aim of studies focused on the area of accounting history is not only centred on the analysis of the accounting techniques used but has now evolved in such a way that any accounting study of an entity entails an analysis of the economic and social context of the period under study. For this reason, studies in accounting history make important contributions to the area of economic history.

We will begin our research by contextualising the Spanish political situation during the first half of the 19th century. We will then focus on the Cathedral Chapter of Seville, the impact of the disentailment processes and the commission created ad hoc for the process: the Commission for the Alienation of Properties Belonging to the Holy Church of Seville. Subsequently, we will analyse the sales procedure carried out by the commission, its administrative management and the accounts presented to the civil authorities. Finally, we will study the appraisals before the sale and the leases lost in the selling process to reach a series of conclusions.

1.1. The disentailment process in Spain (1798 - 1924)

Between the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century, Spain underwent a very turbulent period politically (including liberal revolutions and successions in government), economically (the industrial revolution) and socially (the rise of liberals, merchants and the bourgeoisie). This period witnessed the Napoleonic invasion and the subsequent War of Independence, which led to the economic ruin of the State Treasury (De la Iglesia, 2008). The military uprising of 1820 initiated the so-called Liberal Triennium, in which ties with the Church were broken. In 1833, the first of the three Carlist wars began, and the victory of the liberals helped to maintain Queen Isabella II on the throne until 1868.

During this changing period at the beginning of the century, the State needed to raise funds to pay for the various wars it was fighting, so the confiscation of real estate owned by the Church, the major holder of the same, began1. This consisted of "the legal act (...) under which the depreciated property ceases to be depreciated, returning to the condition of free property of private and ordinary ownership" and, more specifically, "... their holders lose them, they pass to the State, under whose dominion they are 'National Assets'. Subsequently, the State sells them to private individuals and when the purchasers acquire them, these goods become 'free goods'" (Martínez, 1886). Within this disentailment process, five phases can be distinguished:

a. First Disentailment: Godoy (1798 - 1808)

The first Spanish confiscation process occurred during the reign of Charles IV. Although it was commonly known as "Godoy's", it was triggered mainly by the deficit of the State's public finances. These measures aimed to expropriate property from the dead hands of colleges, the Jesuits and the Church’s charitable institutions, such as hospitals and confraternities. However, to achieve this objective, Charles IV obtained the Papal Bull from Pius VII in 1806, authorising him to dispose of the properties belonging to churches, monasteries, convents and ecclesiastical foundations. At the end of this period, in 1807, properties whose owners were cathedral councils were auctioned (Lorenzana, 1997). Sánchez (1994)2 maintains the hypothesis that most of the properties sold during Godoy's disentailment did not form a part of ecclesiastical patrimony, and the Church did not expressly object. In the case of the city of León, the institutions that suffered most from this confiscation were confraternities and foundations, whose properties outnumbered those of the Cathedral Chapter of León (Lorenzana, 1997).

The magnitude of this first process has been studied by authors such as Herr (1971), who estimates that the total amount of goods lost by the Church in southern Spain during this period was 20%.

b. Second Disentailment: Joseph Bonaparte (1808 - 1814)

When the French took power in Spain, another disentailment process occurred, aimed at reconciling the Church with the new State economic organisation (Barbastro, 2008). This resulted in reducing the number of ecclesiastics and, of course, the sale of ecclesiastical property. Despite Joseph Bonaparte's attempts to bring the Church to his side by proclaiming Catholicism the official faith in Spain, it was fiercely opposed to French control (Rodríguez, 1999).

During the government of Joseph I, the first Plan for the structural reform of the Spanish Church was drawn up. It was developed by the Abbé de Pradt, Napoleon's senior chaplain. This Plan aimed to subject the Church to the power of the State by stripping it of all its assets and revenues, in this way, reorganising the State's economy and reducing the public deficit.

This plan was not carried out at that time but served as a basis for the changes implemented by the Cortes of Cadiz (1812) and the Liberal Triennium (1820-1823) (Barbastro, 2008).

Following the objective of this plan, on 4 December 1808, Joseph Bonaparte issued the Chamartín Decrees in which he dealt a severe blow to the nobility, institutions and the Spanish church (Barbastro, 2008). The Inquisition was abolished and the number of convents was reduced because they were too numerous and did not contribute to the nation’s progress (Barbastro, 2008).

Nevertheless, Napoleon's government did not abolish tithes, which were the principal source of income for the ecclesiastical state (Hernández, 2011) but allocated all this revenue to the maintenance of the army (Fernández, 2018; Mercader, 1983). Tithes were taxes levied on ten per cent of grain harvests and were managed entirely by the Church, which distributed them among the clergy, the state and the laity.

c. Third Disentailment: The Liberal Triennium (1820 - 1823)

The Liberal Triennium saw disentailing property as the solution to clear debts incurred by the State once again. This time, the movable and immovable assets of the monastic, military and inquisitorial orders underwent this process. It was an urban phenomenon centred on male ecclesiastical institutions (Gesteiro, 2002), which laid the foundations for the subsequent Mendizábal disentailment. The liberals in government damaged their relationship with these ecclesiastical institutions by showing the population the advantages of disentailing assets to alleviate public debt and using these funds for education and infrastructure. Simultaneously, a policy to reduce the administrative and economic autonomy of the Church by subordinating religious power to civil power was enacted (Rodríguez, 1999). In rural areas, the effects of the confiscations favoured landowners, who enlarged their territories at the expense of charities and hospitals. These institutions saw their source of funding disappear and therefore stopped providing services to the most disadvantaged (Hernández et al., 2008). Furthermore, with the publication of the Decree of the Cortes Generales of 29 June 1821, the income of these entities was further reduced, as it decreed that "All tithes and first fruits will be reduced by half..." (Campos, 2007).

d. Fourth Disentailment: Mendizábal (1836 - 1855)

During the reign of Isabella II, more specifically during Maria Cristina’s regency, the most famous disentailment of all occurred: the confiscation of Mendizábal, which took place between 1836 and 1837. At the time, Spain was still in the throes of an economic and social crisis, made worse by the Carlist uprisings from 1833 onwards. Immersed in this situation, the Government enacted a series of provisions and decrees whereby the assets of religious congregations, except teaching institutions (Ródenas, 2013) and convents, were transferred to the State, which would later be responsible for auctioning them publicly. With the change of regency in 1840, Baldomero Espartero was also responsible for selling estates and shares of the secular clergy (Carmona, 2008).

This difficult situation for the ecclesiastical entities was compounded by the suppression of tithes with the Royal Decree of 29 July 1837 (Campos, 2007).

e. Fifth Disentailment: Madoz (1855 - 1924)

The disentailment that brought about the greatest number of sales was that of 1855, during the period known as the Progressive Biennium. With the General Law of Civil Disentailment of 1 May 1855, D. Pascual Madoz, Minister of Finance during this period, declared communal properties belonging to the clergy, confraternities, military orders, pious works and, for the first time, not only Church, but also State and town councils, for sale. This was one of the most far-reaching enactments with the most significant consequences for the Spanish economy and society, as lower-quality, more parcelled farms were put up for sale. These were less attractive to large buyers, thus allowing the peasantry to become landowners (Moreno, 2015). According to the calculation made by Moreno (2015), the total number of hectares put up for sale reached 5 million, which represented 10% of the national territory.

It is worth noting that in this last disentailment process, two periods can be clearly distinguished:

From 1855 - 1856: Period in which the Law of Disentailment was fully applied. This period ended in 1856 with the Royal Decree of 14 October, in which some provisions of the 1855 Law were repealed, bringing the process to a standstill (Campos, 2007) (Moreno, 2015). The leading cause of this suspension was the litigation filed by the Church during the Progressive Biennium. In 1860, an agreement was reached between the Church and State, which was endorsed in the Agreement-Law of 4 April 1860. This agreement suspended the sale of assets that had not been sold, and the Church accepted the sales made during the Progressive Biennium in exchange for registering the capital in the consolidated Public Debt at 3% (Campos, 2007; Moreno, 2017).

From 1858 - 1924: This second period starts with the publication of the Decree of 2 October 1858, in which it is stated that ecclesiastical goods will be excluded from auction, as indicated above.

Finally, the study by Rodríguez (1999) presents a summary of the total number of estates sold in the period between 1836 and 1867, which includes the 4th disentailment by Mendizábal and part of the 5th disentailment by Madoz. Both were important confiscation processes aiming to sell agrarian property and raise funds to pay off public debt and finance the Carlist War. The overall figures for the disentailment processes between 1836 and 1867 are as follows:

Table 1. Farms sold in the disentailment process between 1836 and 1867

| Concept | Total | Belonging to the clergy | % of Clergy over total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rural properties sold | 416,986 | 300,376 | 72 % |

| Urban properties sold | 60,417 | 38,905 | 64 % |

| Appraisals (in million reais) | +4,106 | +2,260 | 55 % |

| Sale price (in million reais) | +8,426 | +5,043 | 60 % |

Source: Rodríguez (1999, p. 209).

This process of massive land sales did not achieve its objectives since the land was transferred into the hands of aristocrats and the bourgeoisie, who formed large estates. Furthermore, most of the sales were not paid for in cash but with royal vouchers, which meant that the problems of the State Treasury were not solved with this measure (Rodríguez, 1999).

2. The disentailment of the Cathedral of Seville

The Cathedral Chapter of Seville was one of the most powerful institutions in the south of Spain from a religious, economic, political and cultural point of view during the contemporary era. Before the beginning of this period, it had immense real estate patrimony and substantial income from tithes (Hernández, 2010).

The Cathedral Chapter traditionally divided its patrimony into "houses", i.e., urban properties, and "estates", made up of rural properties. In turn, it subdivided these into endowments (pious works), factory and chapter property. Respecting the nomenclature already in use, we understand inheritances as properties received from the distribution of land in Seville after the reconquest of the city in the 13th century. These estates and houses were so numerous and of such great value that they constituted the basis of the Chapter’s rich patrimony (Rubio, 1987, p. 13).

According to Hernández (2010), the Cathedral Chapter of Seville owned a total of 1,508 real estate properties, traditionally divided into houses, or urban properties, and estates, made up of rural properties. The effective ownership and, consequently, the fruits obtained from these properties were given to three very different groups: a) endowments (pious works), Fabrica (for the maintenance of the temple and worship) and the Mayordomía (to be distributed among the members of the Cabildo). These properties were rented and accounted for most of the Chapter's income since money collected from tithes began to decrease and finally disappeared in 1837 (Campos, 2007).

2.1. The first disentailment of the Cathedral of Seville

All the documentation preserved on the effects of this first disentailment process appears in the book entitled "Fincas vendidas por el Rey en tiempos de Godoy (1807)" 3 (Estates Sold by the King During Godoy's Tenure (1807)). The book in question is small (half a quarto), sewn with a leather cover. The table of contents lists the properties (organised by streets) belonging to the Cabildo, Fábrica and Dotaciones. Inside the book, the most relevant information about the property sold is indicated on each page:

Ownership of the property. Whether it belonged to the Cabildo, Factory or Donations.

District where the estate in question was located.

Protocol number of the sale.

Notary where the sale took place.

The exact address of the property.

Name of the tenant of the estate, together with the annual rent paid.

Auction of the estate: Information is given on who bought the property and the amount paid for it, indicating whether it was paid for in cash or with real vouchers.

Date of the sale.

Below, we have transcribed a couple of examples4:

2

Cabildo

Alfalfa

Protocolo 1 310 n 7 Tomas Antonio Díaz; Calle Mesones n 17, Francisco Frisco 984 r.

Rematada en Joaquín Cinicezgue por 24.750 r en vales que entraron en la caja en 16 de diciembre de 1807.

Here we find the sale of property no. 17 on Calle Mesones, located in the Alfalfa district, which belonged to the Cabildo of the Cathedral of Seville. The deed of sale has protocol number 310 n 7 by the notary (we presume) D. Tomás Antonio Díaz. Mr. Francisco Frisco, as lessee, pays annually the amount of 984 reales. Finally, it is indicated that the amount of the sale was received in vouchers of 24.750 reals that entered the cash box.

Two circumstances about these data are striking: first, the fact that no auction process is mentioned, only the person to whom the property was auctioned and the amount paid; and second, that it is expressly stated that the money "entered the cash box", implying that the Cabildo collected the sales and then remitted the proceeds to the Crown.

By compiling all this data, we have made the following table showing that the Cathedral Chapter was obliged to sell 205 properties, which contributed a total of 12,070,173 reales and 27 maravedíes to the Crown.

Table 2. Number of Seville Cathedral estates sold in Godoy's confiscations (1798-1808)

| Cabildo | Factory | Allocations | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of properties sold | 66 | 4 | 135 | 205 |

| Auctions | 2,304,653 r | 36,921 r | 9,728,599 r 27 mrv | 12,070,173 r 27 mrv |

Source: ACS Chapter fund, Section II Chapter table, box 9194 Properties sold by the King during Godoy's tenure (1807). Own elaboration.

Unfortunately, we have not found any documents detailing the obligation of this sale or the liquidation of this money to the State. In any case, it is striking that instead of seizing the assets, as had been done and would later be done in a generalised way, the sale and collection procedure was delegated to the Cabildo, undoubtedly trusting its administrative capacity and experience to manage the sales.

In short, if Herr (1971) estimated the total amount of ecclesiastical real estate disentailed in this first phase at 20%, the Cathedral Chapter experienced a similar reduction, around 15% of all its real estate properties.

2.2. The second disentailment of the Cathedral of Seville. Subsidy, excusado and noveno decimal

To understand the second type of disentailment (indicated in the introduction) imposed on the Cathedral Chapter of Seville, which we have called the suggested sale, we have to go back to the 16th century. At that time, taxes were introduced in favour of the Crown, called subsidy and excusado to defend Christian nations against heretics and infidels (Hernández, 2010). The subsidy was a tax levied on all the income of the ecclesiastical entities. The amount per five-year period was 420,000 ducats for all the ecclesiastical entities in the kingdom of Spain. The excusado was applied to the rents obtained on the first house of each ecclesiastical entity, and a five-year rent of 250,000 ducats was established to be paid to the Crown. These taxes, from their beginnings in the 16th century until the beginning of the 18th century, did not vary. However, during the 18th century, they were reduced due to the obligation to pay in a certain currency (Iturrioz, 1987). Later, at the beginning of the 19th century, due to the Crown’s economic difficulties, Pope Pius VII issued another brief on 3rd October 1800 granting the King the right to charge an extraordinary noveno of all tithes for a period of 10 years to pay off the vouchers issued by the State. This new tax was called the "Noveno Decimal".

During the period between the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century, the King asked the Pope to allow certain extraordinary subsidies on the taxes levied on the Church. This was due to the Crown's need for funds to finance the various wars in which it was involved.

At the time of our research, we have evidence of two Escrituras de Concordia (Deeds of Concord) with very similar characteristics, both of which requested advances in grace. These deeds were:

Deed of Concord5 by the grace of the Excusado of 1,798 granted for 25 years. Its annual contribution amounted to 1,102,083 reales for the Diocese of Seville. On this occasion, the State requested an advance of 10,000,000 reales for State emergencies.

Deed of Agreement6 on the Noveno and Excusado of 1814. In this one, the annual amount is increased to 2,900,000 reales. As in the previous Concordia, the State requests an advance of 8,700,000 reales.

The amount to be collected by the diocese was very high and obliged the Cathedral Chapter, as the representative body of the bishopric, to make an effort to organise, collect and advance these amounts. However, this last Concord was a turning point for the Cathedral Chapter of Seville, as we shall see. This was due to the annual amount, which doubled the previous Concord, and the form of payment. This Concord of 1814 obliged the diocese of Seville to pay the State 2,900,000 reales per year from 1815 to 1824. In addition, the Chapter was again required to advance the King part of the amount, specifically, the equivalent of three annual payments, i.e., 8,700,000 reales, on account of the Noveno Decimal and Casas Mayores Excusadas.

To comply with this new imposition, the Cabildo had no choice but to borrow again ("tomar capitales") from faithful lenders with interest ("réditos" or "premios") ranging from 0% to 6%. Interestingly, this financial cost, thanks to the agreement with the State, could be gradually deducted from the annual amounts to be paid in Excusado and Noveno.

In addition, a certain amount would be deducted from each annual payment made by the Cabildo to redeem part of the capital taken to cover the advance. It was agreed that this would be done in the following way:

In the 1st Triennium (1815-1817): 500,000 reales would be deducted from the annual quota of 2,900,000 reales for the repayment of the capital of the advance.

During the 2nd Triennium (1818-1820): 700,000 reales per year would be deducted from the annual quota.

And finally, in the 3rd Quadrennium (1821-1824): 1,275,000 reales per year would be deducted from the quota.

The following table shows the total amount to be paid in each period, as well as the amount to be deducted.

Table 3. Summary of amounts satisfied in the 1814 Deed of Concord

| Period | Total Quota | Discounts7 | Quota Paid | Outreach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1º Triennium | 8,700,000 r | 2,947,671r 13 mrv | 5,831,044 r 7 mrv | 78,715 r 20 mrv in favour of the Cabildo |

| 2º Triennium | 8,700,000 r | 3,434,509r 5 mrv | 5,053,839r 27 mrv | 211,650 r 2 mrv against the Cabildo |

| 3º Four-year period | 11,600,000 r | 7,016,995r 28 mrv | 5,588,296r 10 mrv | 1,005,291 r 30 mrv against the Cabildo |

| Total | 29,000,000 r | 13,399,176r 12 mrv | 16,473,180r 10 mrv |

Source: ACS Chapter fund, Section II Chapter Table, box 11955 Accounts of the Deed of Concord, 1814. Own elaboration.

Therefore, the agreement implied a financial advance of the next decade's taxes, which was difficult for the Cathedral Chapter to raise. We do not have information about how many loans were requested to meet this initial payment. However, we do know that almost twenty years later (on 10 July 1834), the Cabildo made the difficult financial situation it was suffering clear in a letter to the King, as the amount owed to lenders of capital "at a premium" amounted to 12,846,638 reales and 22 maravedíes, which they wished to redeem, "as is only fair".

The same letter acknowledged that due to the REAL decrees issued by the Government regarding the reform of the clergy, the creditors distrusted the future solvency of the Cathedral Chapter and urgently demanded "their capital". This situation was overcome by "admitting more capital and thus being able to redeem those that were urgently needed" (i.e., renewing the loans with other creditors), but the time came when no new lenders could be found.

These complex circumstances were compounded by a bad harvest, a cholera epidemic in several villages of the archbishopric and continuous "requests for relief" from local and provincial authorities8, who were told that their "very meagre means" were necessary.

Consequently, the Chapter of the Cathedral of Seville appointed a commission within the Diputación de Negocios9, made up of five capitulars: the Archdeacon of Ecija, Pedro de Vera, Canon Nicolás Maestre, Canon Juan Antonio de Urizar, the Rationer Miguel Casimiro de Orta and the Prelate Cristobal Ruíz de Salcedo.

2.3. General Clearance of Accounts and Settlements Commission (1833-1839)10

On 26 June 1834, a report issued by this Commission, together with the Canons Manuel Carassa and Francisco Pereira, stated the reasons why the Chapter was going through this "painful" situation and provided possible solutions to solve it.

The Commission concluded that two main causes had directly led to this situation. The first was the "maintenance and preservation of the decorum and splendour of divine worship" and the second was the "preference always for all kinds of sacrifices rather than the sale of property". In short, it implied that the Chapter had substantial "fixed expenses", its income was insufficient and it had neither the funds nor the capacity for additional indebtedness.

Faced with these circumstances, the solutions that the Commission established as a priority were to sell properties to redeem outstanding capital and revenues and reduce "expenses of all kinds in the management of this Holy Church".

It therefore established a series of measures that we can group into two main blocks:

rational reduction of expenses, including not filling vacant positions for Cabildo members since they were paid a salary. To plan for this, the situation of all the Cabildo's offices would be studied with greater emphasis and detail than usual.

selling real estate to repay loans taken out at high-interest rates.

Considering this report, on 27 June 1834, the Chapter requested a REAL Licence to sell its properties by authority of the REAL Decree of 17 June 1834, which indicated that ecclesiastical corporations had to request this licence before selling their properties.

The request was issued on 10th July 1834, and, together with the list of outstanding loans, it was handed over to a deputation made up of the Chantre, Mr. Manuel Tasiego and the Canon Mr. Juan Nicasio Gallego on 2 July 1834. They were to promote and activate this request in the Ministry of Grace and Justice as soon as possible and with "happy success".

Finally, their efforts were successful, and on 15 February 1835, a Real Order was received granting the Real Licence to sell the properties, with the obligation to invest the income only to remit outstanding capital and interest.

3. Commission for the disposal of properties (1835-1838)

Following the report issued on 10 March 1835 by the Commission of Arrangements, a commission was created solely to sell properties belonging to this Holy Church. It established guidelines to carry out the sale, taking into account the seriousness and delicacy of the matter.

It was called the "Commission for the Sale of Properties Belonging to the Holy Church of Seville". It operated between March 1835 and May 1837, between the Royal Order of 15 February 1835, which granted the licence for the sale of properties and the surrender of capital, and the Royal Order of 28 April 1837, which called for this activity to cease.

Following the rules established by the Settlement Commission, a licence for the sale of the Chapter’s properties had to be requested from His Excellency the Prelate, and the sale had to be preceded by an appraisal of the property, carried out by the Chapter's experts or by those appointed by the commission.

An important detail appearing in the rules is that neither agents nor corregidors were allowed to participate in the sale of properties. This indicates that the intention was to reduce the costs of the sale to a minimum so that all the proceeds would be used solely to repay the capital and accrued interest.

It was decided to be scrupulous about the use of the funds obtained from the sale of properties, as the commission made it clear that they were not to be invested for any other purpose, however serious or urgent, other than the repayment of loans. For this reason, a separate fund was set up, to which neither the accountant's nor the clerk's office had access.

The "manner to be observed in sales" was established by the commission and consisted mainly of "hearing" all those interested in buying houses and subsequently setting a day and time for any interested party to place the highest bid for the house (auctioning procedure). To this end, all the necessary publicity would have been given with enough time for it to be effective.

This process of disposing of the Chapter's properties was suspended with the RO of 28 April 1837. For this reason, the Cathedral Chapter sent the appropriate reports on the sale of the properties by the three commissions to the Ministry of Grace and Justice, who analysed all the documentation submitted. His Majesty issued the RO of 12 December 1837 authorising the continued sale of properties belonging to the Holy Church of Seville to redeem the outstanding capital. We will now focus on the first period of property sales, describing the management system used in this procedure and the process of surrendering the capital. Finally, we will analyse the economic consequences of this process for the Holy Church.

3.1. Procedure for selling properties

We must first look closely at the rules established by the General Clearance of Accounts and Settlements Commission, which set out the guidelines for sales.

In these guidelines, the first step is to request a licence from the Prelate of the Diocese and then carry out an appraisal of the property before putting it up for sale.

The priorities that the Cabildo established to dispose of the properties were as follows:

Plots of land "since it is not possible to build on them".

Houses that are "very old" or are less productive.

No rural property shall be included in the sale, except for small farms that are difficult to manage due to their distance.

Properties encumbered with pious charges shall not be sold11.

We understand that properties that are not profitable (plots of land and houses that need costly renovation) or would entail legal problems (properties with encumbrances) would be better to sell. We also assume that exploited rural properties would provide a higher income than urban rentals.

Once the properties had been appraised and authorised by the Prelate, the sale of the property was advertised in the Diario de Comercio of Seville. This was done until September 1835, when, due to the political situation, private agents were used to spread the word about the properties available. In this way, the properties were advertised, and an estimate of their sale value was obtained.

Subsequently, those interested in buying had to submit their bids within the deadline set by the commission. All the bids were then studied, and a day and time were set to "hear" other possible higher bids than those submitted. Finally, the sale was awarded to the highest bidder.

Each of the sales made by this commission generated a dossier containing the following documentation 12:

Document or order issued within the Diputación de Negocios by the commissioners in charge of property sales. It stated that the buyer must pay the government “alcabala”13, which included the cost of the deed and the payment of half a per cent. In addition, payment was required to be made in "current currency", payment with paper or state vouchers was not allowed. Once the conditions had been indicated, the offers were listed, and the most favourable for the Cabildo was chosen.

The appraisal of the property being sold. This report on the value of the property is of great value, as it provides information describing the characteristics of the property: which properties it borders, its rooms or alcoves and floors, the surface area of the property in square metres and the age of the property. At the end of the report, the experts ratified the valuation based on the "masonry" and "carpentry" of the building.

The application to the Governor of the Archbishopric of Seville for a licence to sell. This request was issued after the commission determined the best offer to buy the property. This fact, in principle, contravenes the established rules, as the licence was requested before the sale.

The licence granted by the Archbishop of Seville.

3.2. Account books of the property disposal committee

To manage each of the tasks assigned to this commission, the Cabildo appointed eight people as members, namely: Nicolás Maestre, Pedro de Vera, Manuel Carrasa, Diego Hidalgo Barquero, Francisco Pereyra, Ignacio Tenorio, Miguel Casimiro de Orta and Cristóbal Salcedo.

Each of them had established functions within the commission. Specifically, Pedro de Vera and Manuel Carrasa acted as accountants. Nicolás Maestre, as the Cabildo's chief accountant, simply supervised the rendering of accounts presented by the former.

The commission managed its accounts using the Charge and Data method, as was customary in this entity (Hernández, 1998). In this accounting system, accounts were rendered to third parties, and the commission accountants played a fundamental role in their control (Villaluenga, 2013). Three books were used to control funds:

Cash receipt book

Outgoing funds ledger

Drawing ledger

The system was simple: first, the entry of funds paid by property purchasers was recorded, the amount of which was kept within the commission. Subsequently, according to the criteria established by the commission, the capital to be

redeemed was recorded in the book of outgoing funds, including the income from the same. Lastly, the commission's accountants ordered the commission's depositary to pay the amounts designated in each of the bank drafts issued, which could contain more than one entry in the book of outgoing payments.

1. Cash receipt book. Commission for the sale of properties. Year 1835

This book records the commission's collection rights from the sale of the properties owned by the Cathedral. The entries were made provisionally on the date of the public act that allowed higher bids to be presented. We have located more than 300 notes.

Each entry contained the details of the property sold: street, government number and ownership (Cabildo or Fábrica), as well as the details of the buyer and the amount of the sale.

All entries were issued by the commission’s accountant for property sales and were addressed to the depositary, who had to issue a letter of payment to the interested party. Without this letter, the sale would not be valid.

As an example, we show the literal transcription of the content of a note:

"The accountant of this commission for the sale of properties will order the depositary of the same to receive from D. Manuel Anastasio Ruiz, neighbour of this City, forty-three thousand reales de vellón for the houses before D. Yiaba Salvadora del Cerro, Gradas n 9 de Gobierno of the property of the Factory that we have sold him, and once the delivery is certified, he will issue the corresponding letter of payment, which we will sign to the interested party, without which requirement it will not be valid. Seville 3 April 1835".14

The notes are signed by the accountant Miguel Casimiro de Orta from March 1835 to 5 September 1835, and later by Manuel Carrasa.

2. Book of funds issued by the commission for the sale of properties and redemption of capital (1835-1840)

In contrast to the previous book, the notes in this output book are not signed. They record the repayments of capital taken to attend to the emergencies of the Chapter table and payment of the corresponding revenues.

Specifically, each annotation indicates the name of the lender and the amount to be paid, as well as whether it corresponds to the total amount of the loan or a part of it. Finally, there is an account of the interest imposed by the Chapter table.

Example of an output book entry:

"On 3 April 1835. To Mr Manuel de Retoqui 100,000 r., the remaining 70,000 r. of a capital of 120,000 r. that he had imposed on the account of those taken for the emergencies of the Chapter house, and the remaining 30,000 r. on account of another capital of 160,000 r. that he has imposed on the same table, both at 6% according to the agreement of the commission appointed for this purpose, dated 3 April 1835."15

As we can see in this case, 100,000 reales corresponding to two loans were repaid, but no interest was paid on them.

3. Book of bills of exchange for the sale of properties. Outflow of funds (1835-1839)

Once the entry had been made in the exit ledger, a cheque was issued by order of the accountant so the depositary could pay the lenders.

As a general rule, several entries were made in the issue book indicating on which page the entry was made, the amount to be paid and whether it was all or part of the loan capital.

All of the bank drafts were signed by Mr. Pedro de Vera and Mr. Manuel Carrassa.

Here is a transcription of a letter of credentials:

3.3. The Commission’s accounts for the Alienation of the Properties of the Holy Church of Seville

The Commission for the Disposal of the Properties of the Holy Church of Seville had to present a summary of its accounts to the Chapter, or, in other words, "an account and justified reason for the operations". Therefore, three accounts were presented corresponding to three different periods, which are referred to in the documentation as the first, second and third commissions, functioning as one for all practical purposes. The accounts submitted for each period or commission correspond to the following dates:

The 1st commission (or period) for the alienation of properties carried out its work between 28 March 1835 and 7 March 1836.

The 2nd commission (or period), from March 1836 to February 1837.

The 3rd commission (or period) was only in operation from 14 February 1837 to 3 May of the same year.

In each of the summaries issued by each commission, all the books described above were pooled, and the amounts obtained from the sales were accumulated, presenting a total account with the Charge and the Data for the period.

The Charge includes all the income obtained from the sales of the properties belonging to the Cathedral of Seville, including urban and rural properties. The Data indicates the payments that were made, which are mainly repayment of capital, payment of outstanding interest and miscellaneous expenses.

In the Charge, the entries are grouped by urban and rural properties, each containing the following information: street of the property, government number, the rent obtained, the appraisal of the property and the final price of the sale or auction.

In the Data, there are three blocks. Firstly, the capital redeemed, where the name of the lender is given, the percentage of the premium and the extinguished yield. In the second block, the yields paid to the capitalists are indicated, without any further details other than the name and the amount paid. Finally, there is a section on expenses inherent to the commission’s activities (paper, stamps, ink, etc.). In addition, a contribution of 800,000 reales had to be made to the Armaments Board, and the Clavería (another section of the Cabildo) had to be repaid the amount of capital it had surrendered.

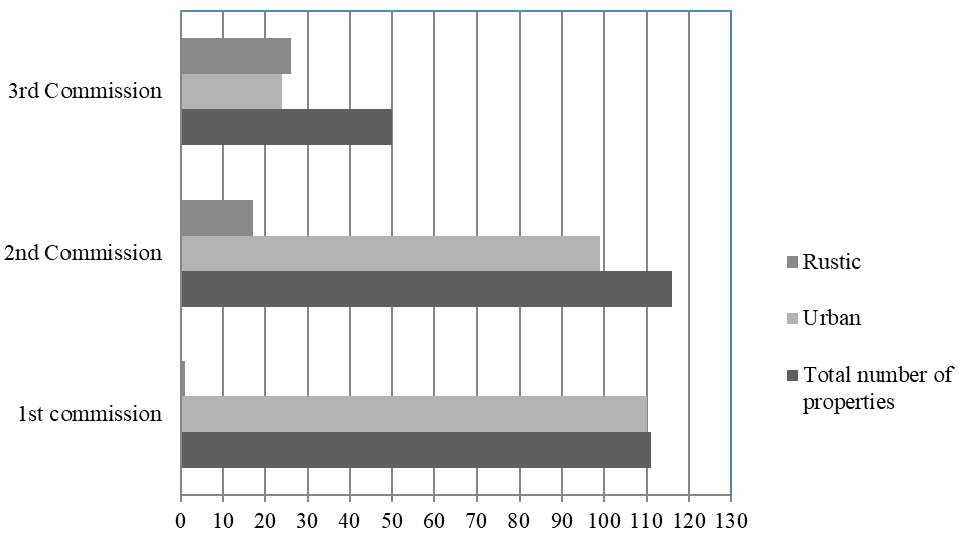

Altogether, a total of 277 properties were sold by the commission, of which 233 (84%) were urban properties and 44 (16%) rural properties.

As can be seen in the following graph, the proportions of properties sold by each commission and types of property vary from 99% and 85% of urban properties sold by the first two commissions to 48% of urban properties sold by the third commission.

Graph 1. Properties sold from 1835 to 1837 by each commision/period

Source: ACS Chapter Fund S. IX General historical fund, Box 11077 doc. 19. Own elaboration

From the sale of all these properties, The Cathedral of Seville obtained a sum of 10,583,407 reales, 9.78% less than their appraised value of 11,730,746 reales.

Moreover, the commission's analysis was so thorough that it included the loss of profit because of these sales in its summaries; it lost 488,636 reales (16,613,624 maravedíes) 17 annually in rent from the properties sold.

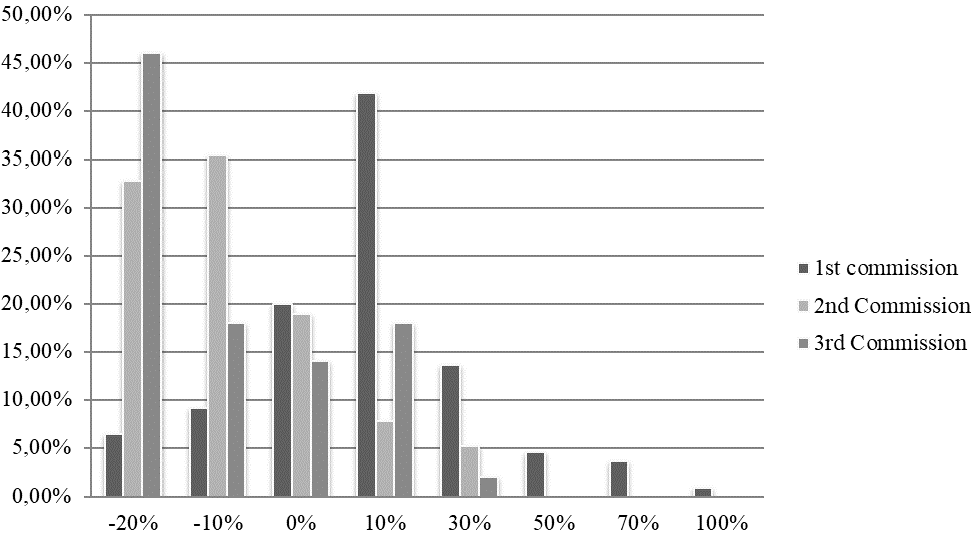

Returning to the question of the differences between the appraisals and the final prices obtained in the sales, we have found nuances between the different commissions, as can be seen in Table 4. In the 1st commission, in weighted average terms, 2.24% was obtained over the appraised value. The differences ranged from -26.21% to 95.53%, with a variance of 0.04 (4%). Therefore, in the first commission, there was considerable variability between what was appraised and what was obtained in the sale of the Cathedral properties, although in overall terms, the positive and negative differences were compensated to give an overall variance of plus 2.24%.

Table 4. Difference between the appraised value of the property and the final sale price

| 1st Commission | 2nd Commission | 3rd Commission | TOTALS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appraisals (Reales) | 3,307,807 | 5,128,835 | 3,294,104 | 11,730,746 |

| Auctions (Reales) | 3,381,993 | 4,402,039 | 2,799,375 | 10,583,407 |

| Total deviation | 2.24% | -14.17% | -15.02% | -9.78% |

| Average deviations | 4.73% | -14.17% | -16.63% | |

| Maximum deviation | 95.53% | 28.83% | 29.17% | |

| Minimum deviation | -26.22% | -41.17% | -43.47% | |

| Variance | 0.04 | 0.018 | 0.022 |

Source: ACS Chapter fund, Section: IX General Historical Fund, box: 11077, Doc. 19. Drafts of the accounts of the three separate property sales commissions submitted to the Government. Own elaboration.

The situation was quite different in the other two commissions. The data shows that with most of the properties sold, the auctions did not exceed the appraised value, with 14.17% lower prices in the second commission and 16.63% in the third. The variance is 0.017 for the 2nd commission and 0.022 for the 3rd. This means that the difference from the established mean is much less than in the 1st commission. There is less variability in the divergence between appraisal and auction, and they are closer to the mean.

To see this imbalance between one commission and the others more clearly, we include Graph 2, which shows the percentages of properties sold in each commission, with the sales margins in the indicated ranges. This interval ranges from margins of less than -20% to margins of less than 100%.

Graph 2. Percentage of properties sold by each commission at the different sales margins set

Source: ACS Chapter Fund S. IX General historical fund, Box 11077 doc. 19. Own elaboration

From this graph, we can see that in the 1st commission, more than 75% of the properties were sold with margins of less than 10%, while in the 2nd and 3rd commissions, they were more than 90%. In the 3rd commission, 45% of the sales were made below 20%, 43% lower than the appraised value in one case.

This indicates that something must have happened in the process of selling the properties that led to more sales below appraised values. We suppose that it could have been an oversupply and reduced demand for properties, or that the properties for sale were not advertised sufficiently. Another possibility is that the properties were not accurately appraised, and the purchase prices were close to the reasonable market value of the property.

We have analysed another magnitude related to these sold properties: rents, i.e., the annual amount of rent obtained from the property before its sale. To relativise this, we have calculated the ratio rent x 100/valuation, meaning the theoretical return in rent on the appraisal of the real estate. As can be seen in the table in Annex 2, this indicator gives values ranging from 1.33% to 15.36%, and the overall average value is 5.22%.

Analysing the theoretical profitability of the properties sold, we can see how it progressively decreased over the three commissions, as demonstrated in Table 5. This allows us to conclude that the most profitable properties were sold first, and then the Cabildo disposed of other, less profitable ones (around 1% less) in the 3rd commission.

Table 5. Annual return on properties vs. Appraised Value

| Rent/Assessment | 1st Commission | 2nd Commission | 3rd Commission |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average | 5.68% | 5.06% | 4.55% |

| Maximum | 15.36% | 13.12% | 11.82% |

| Variance | 0.000498 | 0.000409 | 0.000524 |

Source: ACS Chapter fund, S. IX General Historical Fund, Box: 11077 Doc. 19. Drafts of the accounts of the three separate property sales commissions submitted to the Government. Own elaboration.

4. Conclusions

As we have seen, the "classic" confiscations studied in the literature involving the seizure of real estate were not carried out in the Cathedral of Seville. In the first phase of disentailment, the State trusted the institution and commissioned it to sell more than two hundred properties and remit the proceeds to the Government. At the same time, the tax burden on the Cabildo increased disproportionately, to the point where it was forced to borrow money to cover the advances the State demanded. The lack of funds to repay these loans led to another massive sale of property. Significantly, more than 200 properties were sold in both phases, and the first phase raised almost 20% more than the second phase.

The list of properties sold in this second sales process does not show whether or not Cabildo’s criteria for preferential sales were met. We have only identified the sale of three plots of land. We do not know whether the lands sold were the most distant or the houses sold were the oldest.

What we can conclude from our study is that, in general, there is a multiplying factor relating valuation to the annual rent as a criterion for appraising the property (between 20-25 times the rental value) and that this was possibly used in the appraisal procedure (although in many cases this proportion is not met).

Our analysis also provides significant data on the validity of the appraisals, which, in our opinion, were very realistic and close to the possibilities of the market, bearing in mind that the real estate market was highly variable and unpredictable in the 19th century. Moreover, we have observed that because of experience, the appraisals moved closer to the sale price in each subsequent stage.

As we have seen, the account books did not only include the money obtained from the sales and the expenses involved in the process, but they also recorded the appraisals and bids received before the auction.

In short, this work shows how, faced with a major financial crisis, the Cathedral Chapter was able to carry out two well-organised sales procedures during which it disposed of more than a third of its rented properties. In a serious, transparent and efficient way, it effectively sold off its main source of income. The accounting records show the professionalism, clarity and legitimacy of the procedures.