Improving work outcomes in audit firms: the mediating role of perceived organizational support

ABSTRACT

This study analyses the influence of role overload on organizational commitment and job satisfaction in audit firms, as well as the mediating role of perceived organizational support on these job outcomes. This study is based on 122 survey responses from Spanish auditors. The results show that role overload has a negative relationship with organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Moreover, our findings demonstrate that perceived organizational support mediates both the relationship between role overload and organizational commitment, and the relationship between role overload and job satisfaction. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to analyse the role played by organizational support in the relationship between role overload and auditors’ critical work outcomes. Time constraints and heavy workloads are often perceived as inherent features of an auditor’s job. This particular organizational context makes it necessary to identify variables within a firm’s purview, such as organizational support, which may contribute to mitigating the negative effect of role overload on auditors’ job attitudes.

Keywords: Auditors; Perceived organizational support; Role overload; Organizational commitment; Job satisfaction.

JEL classification: M12; M42.

Actitutes laborales en las firmas de auditoría: el efecto mediador del apoyo percibido por la organización

RESUMEN

Este estudio analiza la influencia de la sobrecarga de trabajo en el compromiso organizativo y la satisfacción laboral en las firmas de auditoría, así como el papel mediador del apoyo percibido por la organización en las actitudes laborales de los auditores. Este estudio se basa en una encuesta realizada a 122 auditores españoles. Los resultados muestran que la sobrecarga de trabajo tiene una relación negativa con el compromiso organizativo y la satisfacción laboral. Asimismo, nuestros resultados demuestran que el apoyo percibido por la organización media el efecto negativo de la sobrecarga de trabajo tanto en el compromiso organizativo como en la satisfacción laboral. Este es el primer estudio que analiza el papel del apoyo percibido por la organización en la relación entre la sobrecarga de trabajo y las actitudes laborales de los auditores. Las limitaciones de tiempo y el exceso de trabajo a menudo se perciben como características inherentes del trabajo de un auditor. El particular contexto organizativo de la auditoría resalta la importancia de identificar variables, tales como el apoyo percibido por la organización, que se encuentren dentro del marco de actuación de las firmas de auditoría y que pueden contribuir a mitigar el efecto negativo de la sobrecarga de trabajo en las actitudes laborales de los auditores.

Palabras clave: Auditores; Apoyo percibido de la organización; Sobrecarga de trabajo; Compromiso organizativo; Satisfacción laboral.

Códigos JEL: M12; M42.

1. Introduction

Auditing has always been considered a high-stress profession (DeZoort & Lord, 1997; Gertsson et al., 2017; Herda & Lavelle, 2012; Nouri & Parker, 2020; Persellin et al., 2019; Sweeney & Summers, 2002). Irregular working hours, excessive workload, especially during the busy season, and the need to work overtime are common job-related aspects of the audit profession (Gertsson et al., 2017; Persellin et al., 2019). These work conditions together with the ‘up or out’ system cause many auditors to leave the profession (Gertsson et al., 2017). Audit firms have expressed concern about the high turnover rates that lead to high hiring and replacement costs and that could result in the reduced expertise of audit teams (George & Wallio, 2017; Gertsson et al., 2017; Hall & Smith, 2009; Hiltebeitel & Leauby, 2001; Nouri & Parker, 2020; Smith et al., 2020). In turn, specialized knowledge gained from long-tenured professional careers is proven to impact audit quality (García-Blandon et al., 2020). Therefore, to retain audit staff, firms and the accounting profession seek to provide favourable work environments that foster auditors’ organizational commitment and job satisfaction (Hiltebeitel & Leauby, 2001) as these are considered determinants of auditors’ intention to leave the audit profession (Chan et al., 2008; Herda & Lavelle, 2012; Nouri & Parker, 2013; 2020; Parker & Kolhmeyer, 2005; Stallworth, 2004).

Occupational stress has long been a matter of concern for human resource managers. Because of its close connection to audit career characteristics and firms’ work environments, in this study we focus on role overload and its impact on job outcomes. Role overload occurs when employees consider that there are too many activities and other work responsibilities under conditions of little time available and restrictions at work (Rizzo et al., 1970).

Numerous researchers have demonstrated a negative relationship between work role stressors and employee outcomes such as job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Currivan, 1999; Curry et al., 1986; Kim et al., 1996). Moreover, organizational studies have analysed the role played by employees’ perceived organizational support in this relationship (Allen et al., 2003; Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002; Wayne et al., 1997). However, accounting-related studies have largely ignored this variable (Nouri & Parker, 2020) and due to the organizational characteristics of the audit firms results might differ in this context.

In this regard, prior research has reported that audit firms’ stressful work conditions negatively impact auditors’ organizational commitment and job satisfaction, leading to high employee turnover rates (Fogarty et al., 2000). However, heavy workloads may have fewer negative effects in the audit context (Christensen et al., 2021). Sweeney & Summers (2002) have shown that auditors accept a high workload threshold before experiencing burnout. Similarly, the literature also suggests that long working hours are often viewed as a personal choice in the accounting setting (Christensen et al., 2021; Lewis 2003). Working long hours is also interpreted as a commitment to the firm (Anderson-Gough et al., 2001). As auditing is a knowledge-intensive profession, auditors’ commitment and productivity are difficult to quantify. In this regard, auditors might equate working extra hours to meet deadlines as achievements in their careers (Lewis, 2003).

Therefore, auditing provides a unique setting in which to analyse the impact of heavy workloads on individuals’ job-related attitudes, as well as to evaluate the role played by the perception of an audit firm’s support in critical work outcomes.

To explain the effect of perceived organizational support on auditors’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment, in this study we rely on social exchange theory as this is one of the most influential conceptual approaches to understanding workplace behaviour and job attitudes (Copranzano & Mitchell, 2005). Social exchange theory provides a conceptual basis for understanding the relationship between employees and their organizations. Employees view this relationship as comprising reciprocal exchanges; therefore, when employees perceive that the organization supports them, they develop a ‘felt obligation’ to care about the organization and to help the organization achieve its objectives (Eisenberger et al., 1986; Eisenberger et al., 2002).

Although there are numerous studies in the management and applied psychology fields based on social exchange theory, this research has been practically ignored in the accounting literature (Nouri & Parker, 2013). Exceptions include Herda & Lavelle (2011; 2012) and Nouri & Parker (2013), who analysed auditors’ organizational commitment, burnout, and turnover intentions through the lens of social exchange theory.

The results show that role overload has a statistically significant negative relationship with organizational commitment and job satisfaction. The results also reveal that role overload is negatively related to perceived organizational support, and that perceived organizational support has, in turn, a positive influence on auditors’ organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Our findings demonstrate that perceived organizational support mediates the relationship between role overload and organizational commitment as well as the relationship between role overload and job satisfaction.

Despite general awareness of the stress to which auditors are subjected, few empirical studies have addressed this issue (Sweeney & Summers, 2002). Further, the auditing profession is continually facing new challenges. The big data environment has changed the way of gathering and evaluating audit evidences, and in consequence, how auditors perform their judgement and make decisions (Cao et al., 2015; Hamdam et al., 2022). Therefore, in this new era, timely research that analyses auditors’ workload is necessary. The present study contributes to the academic accounting literature by analysing the relationship between high workloads and perceived organizational support, which to the best of our knowledge has not been studied before in the audit setting. Moreover, the present study is one of the few accounting-related studies (DeZoort & Lord, 1997; Gendron et al., 2009) that empirically demonstrates the beneficial effects of a reasonable workload on auditors’ relevant work-related attitudes, such as organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Therefore, the practical implications drawn from this empirical research are of the greatest importance to the accounting profession.

It is important to note that most accounting research has not hypothesized mediating effects between role stressors (e.g., role overload) and job outcomes (Fogarty et al., 2000). Therefore, this study contributes to filling a gap in the accounting literature and brings practical implications for audit firms as demonstrates that work conditions influence auditors’ organizational commitment and job satisfaction through the mediating role of perceived organizational support. This result is of major importance to the audit firms. The inherent resource constraints derived from low audit fees make it difficult for audit firms to lessen the amount of work an auditor must perform, especially during the busy season (Cooper et al., 2019; Sweeney & Summers, 2002). Consequently, it is critical to identify variables, such as firms’ support, that may contribute to mitigating the negative effect of role overload and are within audit firms’ purview.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the theoretical framework and the research hypotheses. Section 3 discusses the research method, including sample and variable measurements. Section 4 presents the results of the study, and finally, the discussion of the results and main conclusions are presented.

2. Literature review and hypothesis development

2.1. Social exchange theory

According to Blau (1964), social exchanges refer to ‘voluntary actions of individuals that are motivated by the returns they are expected to bring and typically do bring from others’ (p. 91). These exchanges are based on the norm of reciprocity. As Gouldner (1960) suggests, reciprocity imposes obligations toward another individual in response to the benefit conferred by that party, and the obligation of repayment is subject to the value of the benefit received. In contrast to economic exchange, social exchange generates diffuse future obligations. The moment and nature of the benefits expected in return for the actions are unspecified (Blau, 1964; Copranzano & Mitchell, 2005; Emerson, 1976;). ‘Only social exchange tends to engender feelings of personal obligation, gratitude and trust; purely economic exchange as such does not’ (Blau 1964, pp. 94).

The social exchange framework has been widely employed to explain workplace relationships (Copranzano & Mitchell, 2005). According to this, employees develop social exchange relationships with their organizations (Blau, 1964; Eisenberger et al., 1986; Rhoades et al., 2001; Wayne et al., 1997). Workplace-social exchange relationships evolve when employers support their employees and, in return, employees behave in a manner that produces favourable employee attitudes that benefit the organization (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005).

According to Eisenberger et al. (1986; 2002), employees tend to personify organizations by attributing humanlike characteristics to them. On this basis, Eisenberger et al. (1986) developed the concept of perceived organizational support referring to employees’ ‘global beliefs concerning the extent to which the organization values their contributions and cares about their well-being’ (pp. 501). Perceived organizational support may, in turn, explain the development of employees’ commitment to the organization. Following the pattern of reciprocity embedded in social exchange relationships, when employees perceive organizational support, they develop a ‘felt obligation’ to care about the organization and to help the organization achieve its objectives (Eisenberger et al., 1986; Eisenberger et al., 2002; Rhoades et al., 2001; Wayne et al., 1997).

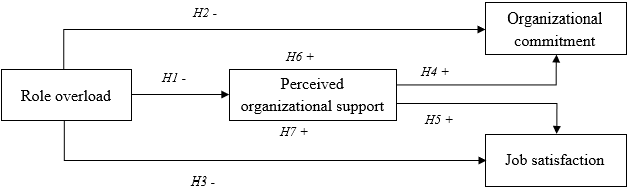

Despite the increased popularity of the concept of perceived organizational support in organizational behaviour research, this concept has not received much attention in the accounting and audit fields. Anecdotal evidence in the accounting field has linked perceived organizational support to whistleblowing intentions (Alleyne et al., 2018). In this study, we develop a series of hypotheses to analyse the effect of perceived organizational support according to social exchange theory. The model presented in Figure 1 includes a particular feature of auditing organizational context (role overload) as an antecedent of perceived organizational support as well as attitudinal outcomes (organizational commitment and job satisfaction) of perceived organizational support that are relevant to the accounting profession.

2.2. Hypothesis development

2.2.1. Role overload

The competitive environment of the audit market places pressure on audit firms to reduce their fees (Barrainkua & Espinosa-Pike, 2015; Ettredge et al., 2014). In their pursuit of profitability, audit firms could minimize the costs of the services by limiting the number of team members assigned to each audit engagement, as well as by reducing the time allocated to the audit client (Christensen et al., 2021; Espinosa-Pike & Barrainkua, 2016; Otley & Pierce, 1996). Work overload is especially high during the busy season, centred around the first quarter of the year, making it very difficult to finish the work at the time assigned (Sweeney & Summers, 2002). Moreover, auditors usually have incentives, such as obtaining a more favourable performance evaluation, to underreport the total hours worked (Almer & Kaplan, 2002; Espinosa-Pike & Barrainkua, 2016; McNair, 1991; Otley & Pierce, 1996; Sweeney & Pierce, 2006). As audit time budgets are usually based on the recorded hours for prior years, underreporting the time employed results in extremely tight audit budgets in the future. These tight audit budgets affect audit staff, as they face unreasonable workloads and time constraints.

Accounting researchers have relied on role theory to explain job-related stress accountants may suffer. Role stressors have traditionally been divided into three dimensions: role conflict, role ambiguity, and role overload (Cooper et al., 2001; Coverman, 1989; Fogarty et al., 2000; Kahn et al., 1964; Rizzo et al., 1970). Applying this theoretical approach, researchers have linked role stressors to many dysfunctional work-related attitudes (Beehr et al., 1976; Fogarty et al., 2000; Jones et al., 1995; Kemery et al., 1985; Schaubroeck et al., 1989; Sullivan & Bhagat, 1992). Role overload refers to job demands that exceed what an employee can reasonably be expected to perform in a given time (Beehr et al., 1976). Therefore, role overload occurs when employees are expected to perform a wide variety of tasks that are impossible to complete within the given time constraints (Kahn et al., 1964).

In this study, we focus specifically on role overload and its impact on auditors’ job-related attitudes. Auditors have been found to experience both quantitative and qualitative work overload (Barrainkua & Espinosa, 2015; DeZoort & Lord, 1997; Espinosa-Pike & Barrainkua, 2016; Sweeney & Pierce, 2006). Quantitative work overload is related to time pressure, while qualitative work overload occurs when individuals perceive that they lack the necessary competence to carry out their jobs (Dezoort & Lord, 1997). In this research, role overload refers to both types of workload.

Understanding the consequences of role overload is particularly interesting in the audit context as time management is a central element of audit firms (Anderson-Gough et al., 2001). Audit recruits anticipate that they will have to face a heavy workload for career advancement and that private time would be available at the service of the firm and the client. By working overtime, auditors display their commitment to the firm and succeed over others in the competition for promotion (Alberti et al., 2020, Anderson-Gough et al., 2001; Ladva & Andrew, 2014). Moreover, some auditors view a career in an audit firm as a stepping stone to better employment opportunities (Bagley et al., 2012). Training provided by firms enhances auditors’ career advancement and, as such, constitutes a form of compensation for them (Nouri & Parker, 2013). In this regard, auditors might be willing to work hard and put extra effort into taking on new responsibilities and benefit from the experience gained in them. Therefore, role overload may lead to different job outcomes in this context.

Although role overload and occupational stress are considered significant features of audit firms’ working environments, evidence of their impact on auditors’ affective outcomes is scant (DeZoort & Lord, 1997; Gendron et al., 2009; Sweeney & Summers, 2002).

Role overload and perceived organizational support

A meta-analysis by Rhoades & Eisenberger (2002) indicated that beneficial treatment on the part of the employer organization, such as favourable job conditions, was associated with higher perceived organizational support. In this situation, employees who perceive that their organization supports them also perceive that help will be available to carry out their jobs effectively and cope with stressful situations (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002). Therefore, employees’ opinions of the policies taken by the management, such as the workload assigned, form the basis for employees’ perception of support from the organization (Hutchison, 1997). Empirical research on organizational behaviour has found a negative relationship between role overload and perceived organizational support (Jones et al., 1995; Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002). However, none of these studies was conducted in the auditing domain, where role overload is the most critical stressor of the work environment (Sweeney & Summers, 2002).

In the particular environment of audit firms working long hours is usually framed in terms of serving client needs (Anderson-Gough et al., 2001). Heavy workloads may seem unavoidable to meet client demands and beyond the control of the audit firm. However, although audit firms may attribute time pressure and heavy workloads to external demands from the client (Anderson-Gough et al., 2001), allocating enough time to complete the audit tasks at hand are decisions made by audit partners and managers (Barrainkua & Espinosa-Pike, 2015). Given the pressure to lower audit fees, in the pursuit of profitability, audit managers attempt to reduce the cost of the services by reducing the time budget (Otley & Pierce, 1996; Sweeney & Pierce, 2006), which leads to role overload on the part of the audit staff. The need to work unpaid overtime is unlikely to be perceived as fair on the part of the auditors. Therefore, we put forward that if auditors feel that enough resources are at their disposal and consider that their job demands are reasonable, they will perceive that their audit firm supports them and cares about their well-being.

Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Role overload negatively influences perceived organizational support.

Role overload and organizational commitment

According to Mowday et al. (1979, pp. 226), organizational commitment reflects an individual’s identification with the organization and is characterized by ‘(i) a strong belief in and acceptance of the organization’s goals and values, (ii) a willingness to exert considerable effort on behalf of the organisation, and (iii) a strong desire to maintain membership in the organisation.’ Studies in management and business organization have found that role overload negatively influences employees’ commitment to their organizations (Currivan, 1999; Örtqvist & Wincent, 2006).

In the accounting literature, there has been growing interest in the organizational commitment construct. Evidence suggests that organizational commitment reduces auditor dysfunctional attitudes, thus improving audit quality (Lord & DeZoort, 2001) and leads to lower levels of staff turnover intention (Aranya & Ferris, 1984; Ketchand & Strawser, 2001: Meixner & Bline, 1989; Reed et al., 1994; Shafer, 2002; Shafer et al., 2002). However, research that analyses the relationship between role overload and accountants’ organizational commitment is still scarce (Sweeney & Summers, 2002). Reed et al. (1994) reported the negative impact of role overload on female accountants’ organizational commitment. Stallworth (2004) found that auditors’ perception of the reasonableness of overtime is positively associated with auditors’ commitment to their firm. In the study conducted by Gendron et al. (2009) among chartered accountants in Canada, the authors analysed the effect of a lack of balance between work, family, and leisure time as a proxy for occupational stress and concluded that its relationship with organizational commitment was insignificant. However, unlike the present study, the sample in the study by Gendron et al. (2009) was composed of auditors as well as management accountants. Previous studies reveal that auditors’ time pressure and job stress are considerably higher than that of management accountants (Larson, 2004). Moreover, the variable role overload employed in this study includes, in addition to the lack of work-life balance, the work pressure felt by auditors and the time devoted to their jobs. Accordingly, the results in the present study might be different and, therefore, we posit the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Role overload negatively influences organizational commitment

Role overload and job satisfaction

Job satisfaction refers to a positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job experiences (Locke, 1976). Job satisfaction has been considered a relevant antecedent of auditors’ turnover intention (Chan et al., 2008, Dole & Schroeder, 2001; Herda & Lavelle, 2012; Nouri & Parker, 2013; Parker & Kohlmeyer, 2005; Reed et al., 1994), and research has shown that work conditions affect job satisfaction. In this regard, heavy workload (Currivan, 1999; Gaertner, 1999; Örtqvist & Wincent, 2006) and undesirable work stress (Kim et al., 1996; Snead & Harrell, 1991) reduce employees’ job satisfaction.

Although some studies have shown that audit firms foster a workaholic culture in which auditors show high tolerance for heavy workloads (Alberti et al., 2020; Sweeney & Summers, 2002). Previous research in the accounting setting has found that role overload affects auditors’ general attitudes toward work, leading to job dissatisfaction (Nouri & Parker, 2020; Persellin et al., 2019). Fogarty et al. (2000) found that among accountants in a diverse range of practices, high levels of role overload were associated with burnout tendencies and, in turn, the burnout condition on the part of accountants led to job dissatisfaction. Similarly, Smith et al. (2018) found that burnout fully mediates the association between auditors’ role overload and job satisfaction.

Therefore, most empirical findings led us to propose a negative relationship between role overload and job satisfaction through the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Role overload negatively influences job satisfaction.

2.2.2. Perceived organizational support

Perceived organizational support and job outcomes

The focus of most organizational research on perceived organizational support has been the prediction of outcomes reflected in employees’ attitudes and behaviours (Wayne et al., 1997). From a social exchange approach, employees who feel support from their organizations reciprocate by developing a strong commitment to the organization (Eisenberger et al., 1986). Perceived organizational support will increase employees’ affective attachment to the organization and increase their expectation that greater effort to meet organizational goals will be rewarded (Eisenberger et al., 1986).

In this same vein, perceived organizational support is believed to increase job satisfaction by meeting socioemotional needs, raising expectations for performance rewards, and signalling the availability of help when needed (Eisenberger et al., 2002; Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002).

Organizational research confirms that perceived organizational support influences employees’ affective reactions to their job, including organizational commitment and job satisfaction (Eisenberger et al., 1997; Eisenberger et al., 2002; Meyer et al., 2002; Randall et al., 1999; Rhoades et al., 2001; Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002; Riggle et al., 2009; Suazo & Turnley, 2010).

The relationships between organizational support and employees’ job outcomes have barely been explored in the accounting and audit fields. Chan et al. (2008) reported that junior accountants who perceived that their audit firms supported them showed a significantly higher commitment to their employing organization. Herda & Lavelle (2011; 2012) found that perceived organizational support predicts auditors’ commitment to their firms. Accordingly, in this study, we posit the following hypotheses regarding the effect of auditors’ perceived organizational support on organizational commitment as well as on job satisfaction.

Hypothesis 4: Perceived organizational support positively influences organizational commitment.

Hypothesis 5: Perceived organizational support positively influences job satisfaction.

Mediating effects of perceived organizational support

Previous literature that has analysed the mediating role of perceived organizational support has found that perceived organizational support mediates the relationship between human resource practices and work-related outcomes, such as affective commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions (Allen et al., 2003; Wayne et al., 1997). Jones et al. (1995) found that perceived organizational support mediates the effect of work stress on employees’ job satisfaction and their level of commitment to the organization.

Studies that have analysed the effect of role overload on organizational commitment and job satisfaction in the accounting setting have tested role overload as a direct antecedent of accounting professionals’ job outcomes (Fogarty et al., 2000). However, it is not clear whether these relationships are direct or, on the contrary, whether important mediator variables, such as perceived organizational support, have been omitted. In line with previous research in organizational studies (Allen et al., 2003), we propose that workload seen as reasonable on the part of the auditors increases perceived organizational support and leads to organizational commitment and job satisfaction because of auditors’ perceptions that the organization supports and cares about them.

To a certain degree, heavy workloads are inherent to the auditing profession, especially during the busy season when most audit firms’ billable hours are generated (Sweeney & Summers, 2002). Reducing workload may be difficult because of the tight audit fees resulting from a competitive audit market. Therefore, this study aims to analyse the role played by firms’ support on auditors’ job attitudes, as many decisions taken by audit firms’ management, such as recognition of job demands, can enhance the perceived organizational support of the auditors.

Therefore, we propose that perceived organizational support mediates the relationship between role overload and job attitudes.

Hypothesis 6: Perceived organizational support fully mediates the negative influence of role overload on organizational commitment.

Hypothesis 7: Perceived organizational support fully mediates the negative influence of role overload on job satisfaction.

Figure 1. Theoretical mediation model of role overload, perceived organizational support, organizational commitment and job satisfaction relationships

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and data collection

To test the hypotheses stated above, we employed a survey as the research instrument. Before distributing the questionnaire, this was sent to a partner of a public accounting firm, who passed it on to a few fellow auditors. The contact auditor indicated that, overall, neither he nor his colleagues had trouble understanding the questions.

Responses were then collected using online survey software. As professionals were to be questioned about sensitive real-life issues as well as in consideration of the strengths of online survey studies, such as ensuring anonymity and the possibility of reaching a large population, we considered this method the most feasible for the distribution of questionnaires. Respondents were assured that the information would be used solely for this study, that participation in the study was voluntary, and that the data collection process ensured their anonymity. The subjects were asked to complete the survey individually. The final survey was distributed in November 2017 among Spanish auditors who were receiving professional training in auditors’ corporations to take the exam for access to the Spanish Official Registry of Auditors. From a total of 200 potential respondents who were undergoing training at the time, 90 responses were obtained. After excluding the responses of the participants who did not complete the questionnaire, 55 responses were included.

The survey was also distributed in April 2018 among professionals taking the master’s degree in auditing at the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Spain (ICJCE), from whom 150 responses were obtained; 67 responses were included in the sample after excluding incomplete questionnaires. In total, 122 responses were used as the sample in the present study.

We compared the responses of the two subsamples. The main difference relates to the years of auditing experience. The auditors who prepare for the Spanish Official Registry access exam have longer experience in auditing since most have worked for an audit firm for more than five years. On the contrary, most auditors who were at that time taking a master’s degree in auditing have worked for an audit firm between three and five years. We then compared the responses to the questionnaire of the two subsamples through independence tests and no statistical differences were found.

3.2. Questionnaire and measurement of variables

The first part of the questionnaire contained general questions about the respondents’ characteristics. Following this, the questionnaire included a series of close-ended questions concerning the variables under study (see Table 3). Participants had to indicate how much they agreed or disagreed with the statements on a Likert scale, ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree).

Role overload. The survey instruments developed for role overload have not received a strong consensus in the literature (Fogarty et al., 2000; Nouri & Parker, 2020), and unlike other scales, the measurement of role overload has remained context-specific to capture quality aspects that vary across occupations (Fogarty et al., 2000, Newton & Keenan, 1987). The six-item scale employed in this research (see Table 3) is based on the role overload scale from Beehr et al. (1976), which has previously been employed in the audit context (Almer & Kaplan, 2002). As in previous studies in the accounting field, an item related to work-life balance has been included (Gendron et al., 2009). In the instrument employed in the present study, a higher score on this scale implies a more attainable workload. To measure auditors’ role overload, we reverse-scored the items. A confirmatory factor analysis (not tabulated) revealed that all pressures loaded in one factor. The factor explained the 90% of the variance.

Perceived organizational support.. This variable was measured using the short version (six-item scale) developed by Eisenberger et al. (1986). Literature provides evidence for the high internal reliability and unidimensionality of this scale (Eisenberger et al., 2002). A confirmatory factor analysis (not tabulated) revealed that all statements were loaded in one factor. All items were loaded above 0.5 for the factor, instead for the item ‘The organization shows very little concern for me (Reversely scored)’. This item was excluded from the factor. This factor explained the 88% of the variance.

Organizational commitment. This variable is based on the instrument developed by Porter et al. (1974), which has been used in many studies in the accounting field (Aranya & Ferris, 1984; Lord & DeZoort, 2001). In this study, we employed a shorter version of the organizational commitment instrument. We included a five-item scale employed by Suddaby et al. (2009) and Gendron et al. (2009). The confirmatory factor analysis (not tabulated) revealed that all statements were loaded in one factor. However the communality of the item ‘I seriously intend to look for a job at another employer/firm within the next year (Reversely scored)’ was too low (0.254) and was excluded from the factor. The remaining four items were loaded above 0.5 for the factor. This factor explained the 67% of the variance.

Job satisfaction. This variable was measured using six items from the index developed by Brayfield & Rothe (1951). This scale has been used in previous studies in the field (Fogarty, 1996; Shafer, 2002; Shafer et al., 2002). A confirmatory factor analysis (not tabulated) revealed that all statements were loaded in one factor. All items were loaded above 0.5 for the factor, instead of the items ‘It seems that my friends are more interested in their jobs than I am. (Reversely scored)’ and ‘I dislike my work. (Reversely scored)’. These items were excluded from the factor. This factor explained the 83% of the variance.

3.3. Participant characteristics

A total of 122 responses were included in the study. The general characteristics of the respondents are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants

| Age | % | N |

|---|---|---|

| Between 20 and 25 years | 10% | 12 |

| Between 26 and 35 years | 59% | 72 |

| Between 36 and 45 years | 25% | 31 |

| Between 46 and 55 years | 6% | 7 |

| Gender | % | N |

| Female | 57% | 70 |

| Male | 43% | 52 |

| Rank in the audit firm | % | N |

| Assistant | 17% | 21 |

| Senior | 48% | 58 |

| Manager | 35% | 43 |

| Auditing work experience | % | N |

| Less than 5 years | 42% | 51 |

| Between 5 and 10 years | 33% | 40 |

| More than 10 years | 25% | 31 |

| Size of the audit firm | % | N |

| Big four | 50% | 61 |

| Medium-sized audit firm | 14% | 17 |

| Small audit firm | 36% | 44 |

| Total sample | 122 |

Most of the respondents (59%) are between 26 and 35 years old, followed by individuals who are between 36 and 45 years old (25%). The majority of auditors in the sample (57%) are female.

Regarding their ranks in the audit firm, 17% of the auditors in the sample are assistants, 48% are senior auditors, and finally, the auditors in the position of managers represent 35% of the sample. Respondents were also asked about their work experience in auditing and, in this respect, 42% of the sample had less than 5 years of experience in auditing, a third of the sample had worked as an auditor between 5 and 10 years old, and finally, 25% of the sample had more than 10 years of auditing experience.

Half of the auditors in the sample work in one of the Big Four audit firms, and 17% of the respondents were employed in medium-sized audit firms, which in this study refer to audit firms with more than five audit partners that are not one of the Big Four audit firms. Finally, 36% of the respondents work in a small audit firm, which, following the work of Azkue (2012), in this study are defined as audit firms with fewer than five partners.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive statistics and t-test results

First, Table 2 displays the descriptive statistics and one-sample T-test results for the variables in this study. These were measured by summing the scale items shown in Table 3 and creating an average.

Data for all the variables under study were collected from the questionnaire sent to auditors. Consequently, we conducted Harman's (1967) Single-Factor Test to check to what extent common method variance is present in our data. The results of the test reveal that there is more than one factor and that a single factor does not account for the majority of variance. This provides some assurance that no problems with common method bias exist.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and mid-point scale t-test results

| Mean | SD | t-test | Sign. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Role overload | 4.621 | 1.728 | 3.969 | 0.000 |

| Perceived Organizational Support | 4.900 | 1.514 | 6.565 | 0.000 |

| Organizational Commitment | 4.643 | 1.401 | 5.073 | 0.000 |

| Job Satisfaction | 4.902 | 1.308 | 7.615 | 0.000 |

The scale anchor of the items that measure the variables is between 1 and 7, thus the midpoint of the scale is 4. Table 2 shows that the auditors in the sample perceive role overload in their jobs, as the mean score is statistically significantly above 4.

The mean scores for the rest of the variables (mean responses above 4) suggest that respondents feel supported by their organization and that the organizational commitment and job satisfaction of the auditors in the sample are high.

4.2. Measurement model fit, convergent validity, and discriminant validity

To verify the dimensionality of the measurement constructs, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was adopted. All factor loadings were significant (p < 0.001), with all measurement items loading on their expected factors. To test the reliability and validity of the constructs, we employed composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) values. Table 3 shows that the CR score ranged from 0.839 to 0.967, which is higher than the recommended value of 0.6 (Hair et al., 2006). The constructs exhibited an AVE between 0.566 and 0.853. This result is higher than 0.5 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), supporting the convergent validity of the measures. Cronbach’s alpha for the variables was between 0.832 and 0.964. Therefore, the scales showed high internal reliability.

Table 3. Results of confirmatory factor analysis

| Construct | Factor Loadings | CR | AVE | Cronbach's alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Role overload | ||||

| The length of my working day is appropriate. | 0.976 | 0.963 | 0.867 | 0.964 |

| This job allows me to have a work-life balance. | 0.942 | |||

| The work pressure of my job is appropriate. | 0.892 | |||

| The physical and mental load at the end of the working day is appropriate. | 0.911 | |||

| Perceived Organizational Support | ||||

| The organization values my contribution to its well-being | 0.957 | 0.967 | 0.853 | 0.964 |

| The organization strongly considers my goals and values. | 0.969 | |||

| The organization cares about my well-being. | 0.922 | |||

| The organization is willing to help me when I need a special favour. | 0.894 | |||

| The organization takes pride in my accomplishments at work | 0.873 | |||

| Organizational Commitment | ||||

| I am proud to tell my friends that I am part of my current employer/firm | 0.819 | 0.839 | 0.566 | 0.832 |

| When someone criticizes my current employer/firm, it feels like a personal insult | 0.712 | |||

| I hope to be working for my current employer/firm until I retire | 0.740 | |||

| My sense of who I am (i.e. my identity) overlaps to a great extent with my sense of what my current employer/firm represents | 0.734 | |||

| Job Satisfaction | ||||

| I feel fairly well satisfied with my present job. | 0.864 | 0.927 | 0.761 | 0.931 |

| Most days I am enthusiastic about my work. | 0.850 | |||

| I like my job better than the average worker does | 0.879 | |||

| I find real enjoyment in my work | 0.896 | |||

Furthermore, the discriminant validity was checked by calculating the square root of the AVE of each construct and comparing this value to the correlation between the two constructs (Table 4). Table 4 shows that the squared root AVE values for each construct (written in italics) were larger than the correlation of the respective construct with the other constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), supporting the discriminant validity of the measures.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics, correlation analysis and construct discriminant validity

| Construct | Role Overload | Perceived Organizational Support | Organizational Commitment | Job Satisfaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Role Overload | 0.931 | |||

| Perceived Organizational Support | -0.410*** | 0.924 | ||

| Organizational Commitment | -0.272*** | 0.737*** | 0.752 | |

| Job Satisfaction | -0.445*** | 0.614*** | 0.623*** | 0.872 |

*** p < 0.01

4.3. Structural equation estimation

Two different structural models were tested. First, we tested Model I that examined the direct path from role overload to both dependent variables, organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Model II examined these relationships including the direct paths as well as the indirect path with perceived organizational support as the mediator variable. Therefore, the two models were tested to determine whether perceived organizational support plays a role as a mediator variable in the relationship between role overload and work outcomes, i.e. organizational commitment and job satisfaction.

We examined the model’s fit by following the fit criteria adopted by Hair et al. (2006) including \(\chi^2\)/df, the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the normed fit index (NFI), and the comparative fit index (CFI). The results displayed in Table 5 show that all indices met the standard cut-off values for both models. The \(\chi^2\)/df was less than 2 for both models. GFI, NFI, and CFI were greater than 0.9 and RMSEA was lower than 0.05. Thus, the measurement models represent a good fit.

Table 5. Model fit indices

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | GFI | NFI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model I | 51.932 | 47 | 1.105 | 0.935 | 0.961 | 0.996 | 0.029 |

| Model II | 117.284 | 105 | 1.117 | 0.901 | 0.949 | 0.994 | 0.031 |

Notes: χ2/df = Chi-Square divided by degrees of freedom; GFI = Goodness-of-fit index; NFI = Normed fit index; CFI = Comparative fit index; RMSEA = Root mean square error of approximation

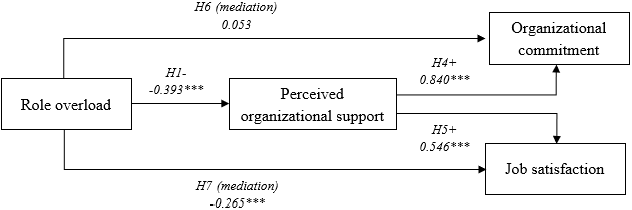

Figure 2 and Table 6 display the results of the structural equation model analysis. The results show that all direct paths are statistically significant. The results in Model I support the direct relationship proposed in H2 and H3 as role overload is negatively related to organizational commitment (\(\beta\) = -0.275, p < 0.01) and negatively related to job satisfaction (\(\beta\) = -0.478, p < 0.01). In regards to Model II, results reveal that role overload is negatively related to perceived organizational support (\(\beta\) = -0.393, p < 0.01), supporting H1. Perceived organizational support was found to have a significant positive impact on organizational commitment (\(\beta\) = 0.840, p < 0.01) as well as on job satisfaction (\(\beta\) = 0.546, p < 0.01), which supports H4 and H5.

To verify the mediating role of perceived organizational support we conducted a mediation analysis adopting a bootstrapping approach. The bootstrap method was used to test the significance of indirect effects through SPSS AMOS27.0, which produces bias-corrected confidence intervals (CI). The significance of the indirect effect was evaluated from 5000 bootstrap samples with a 95% confidence interval. The bias-corrected CI for the mediation effect of perceived organizational support in the relationship between role overload and organizational commitment ranges from -0.349 to -0.110, which does not include 0 in between. Therefore, the indirect effect is significant at the 0.05 level, and H6 is supported. The results for the bootstrap analysis for the mediation effect of perceived organizational support in the relationship between role overload and job satisfaction showed that the confidence interval does not include 0 (lower limit = -0.256 and upper limit = -0.057), and therefore, H7 was also supported. Results in Table 6 show that when perceived organizational support has been introduced in the model the direct effect of role overload on organizational commitment loses its statistical significance, which shows that a full mediation exists between role overload and organizational commitment. In the case of job satisfaction, role overload remains significant, which means that role overload affects satisfaction both directly and indirectly through perceived organizational support. These results are in line with prior research that found that compared to the variable organizational commitment, job satisfaction varies more directly when work conditions change (Currivan, 1999; Mowday et al., 2013). Taken together, these results suggest that perceived organizational support mediates the negative effect of role overload on job outcomes within the specific context of auditing.

Table 6. Structural Equation Results

| Model | Direct effect paths | Standardized coefficient | p-value | Bootstrap results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL 95% CI | UL 95% CI | p-value | |||||

| Model I | H2 | RO → OC | -0.271 | 0.006*** | -0.328 | -0.016 | 0.031** |

| Model I | H3 | RO → JS | -0.478 | 0.000*** | -0.444 | -0.180 | 0.000*** |

| Model II | H1 | RO → POS | -0.393 | 0.000*** | -0.482 | -0.135 | 0.001*** |

| Model II | H4 | POS → OC | 0.840 | 0.000*** | 0.508 | 0.867 | 0.001*** |

| Model II | H5 | POS → JS | 0.546 | 0.000*** | 0.234 | 0.659 | 0.000*** |

| Model II | RO → OC | 0.053 | 0.466 | -0.054 | 0.135 | 0.002*** | |

| Model II | RO → JS | -0.265 | 0.000*** | -0.292 | -0.069 | 0.398 | |

| Indirect effect paths | |||||||

| Model II | H6 | RO → POS → OC | -0.330 | 0.000*** | -0.349 | -0.110 | 0.000*** |

| Model II | H7 | RO → POS → JS | -0.215 | 0.000*** | -0.256 | -0.057 | 0.001*** |

Notes: RO = role overload; OC = organizational commitment; JS = job satisfaction; POS = perceived organizational support; LL 95% CI = lower limit of the 95% confidence interval; UL 95% CI = upper limit of the 95% confidence interval; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01;

Figure 2. Structural path estimates model for Model II. Note: All path estimates are standardized; *** p < 0.01

4.4. Robustness check

The good fit of the model selected supports the causal relations between the variables specified in the model. However, the variables studied could be jointly driven by other omitted factors that difficult the establishment of the causal order. Therefore, another model with different directions has been compared. Instead of testing the mediation effect of perceived organizational support on the relationship between role overload and the two job outcomes (i.e. organizational commitment and job satisfaction), we reversed the arrow and tested the mediation effects of organizational commitment and job satisfaction on perceived organizational support. Results (not tabulated) show that the strength of the effect of organizational commitment on perceived organizational support, as measured by the standardized \(\beta\) coefficient is lower in this alternative model. Moreover, results show that organizational commitment mediates only partially the relationship between role overload and organizational commitment, in comparison to the full mediation found in the original model. In regards to job satisfaction, results in the alternative model show that the effect of job satisfaction on perceived organizational commitment is not significant, which leads us to reject this alternative causal relationship. Therefore, these results provide additional evidence for the robustness of the original model tested.

5. Conclusions

This study aims to analyse the influence of role overload on organizational commitment and job satisfaction in audit firms, as well as the mediating role of perceived organizational support on these job outcomes. The results reveal that role overload is statistically negatively related to perceived organizational support, and perceived organizational support has, in turn, a positive influence on auditors’ organizational commitment and job satisfaction. The results also show that role overload has a statistically significant negative relationship with organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Our findings demonstrate that perceived organizational support mediates the relationship between role overload and organizational commitment as well as the influence of role overload on job satisfaction.

The results corroborate the suggestions from previous studies in other work environments that improving job conditions by establishing more attainable workloads can increase auditors’ organizational commitment and job satisfaction, which in turn may reduce high turnover rates (Currivan, 1999; Gaertner, 1999; Örtqvist & Wincent, 2006; Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002). This result must be understood in the particular organizational context in which auditors carry out their work. Previous research suggests that auditors underreport the total number of hours dedicated to audit engagement (Barrainkua & Espinosa, 2015; Sweeney & Pierce, 2006). As audit time budgets are based on previous years’ reported hours, underreporting the total number of hours worked leads to unattainable time budgets in the future, creating unmanageable workloads for auditors. Therefore, this study highlights that allocating sufficient resources to audit engagement as well as promoting honest time reporting on the part of the auditors could enhance auditors’ organizational commitment and job satisfaction.

The benefits of perceived organizational support on relevant work-related attitudes, such as organizational commitment and job satisfaction, have been highlighted in this empirical study. This finding is consistent with Blau's (1964) social exchange theory as well as with the organizational support model (Eisenberger et al., 1986), which suggests that if employees feel that the organization values them and cares about their well-being, employees will respond positively to favourable treatment on the part of the organization.

Important implications for audit firms can be drawn from this study. The fact that perceived organizational support mediates the influence of role overload on favourable job attitudes suggests that excessive workload on the part of the auditors reduces organizational commitment and job satisfaction because of a lack of perception that the organization supports them. Therefore, this study highlights the importance of organizational support in developing positive job outcomes and reducing employee turnover intentions. Perceived organizational support should be viewed as an important resource within audit firms to counteract auditors’ high workload and stress. Auditing firms may pay attention to the evaluation and appraisal system to make employees feel appreciated and rewarded for their work and extra effort. In particular, during the busy season, when a high workload is sometimes unavoidable, audit staff could cope better with the excessive workload if they feel that their supervisors are aware of and will reward their dedication and achievements. In the same vein, accurate time reporting must be encouraged to avoid bias in personnel performance evaluation. Strengthening communication between lower- and higher-ranking employees as well as a higher participation of staff auditors in the engagement budgets could increase employees’ perception that their firm cares about their well-being.

This study had several limitations. Due to the questionnaire methodology employed in this study, the data for both the predictor and dependent variables were gathered from the same source, which raises the possibility that the research results are subject to common method bias. Several procedural remedies were applied to reduce the effects of common method bias, such as separating the measurements of the variables and including reverse-scored items in the questionnaire.

Although the questionnaire was developed based on instruments used in prior studies, several questions were developed by the authors to gather data on audit-specific issues. Moreover, auditors are difficult to access and are subject to a high workload. Therefore, short versions of the scale were necessary to prevent respondents from abandoning the questionnaire, and these versions may be less reliable than the original instruments.

Further, due to the nature of the groups to which we were able to distribute the survey, the sample does not include audit partners. Results could be different if we employed a sample of partners. Audit partners might be less susceptible to experiencing role overload as they are not primarily involved in the field tasks. Moreover, we could consider that the partners have decided to pursue a professional career in auditing. Therefore, the impact of role overload on partners’ job attitudes might be different and offers an interesting research opportunity.

It is important to note that the survey in the present study was administered before the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 has induced an unprecedented change in accountants’ workplace. The generalization of teleworking as a result of COVID-19 has facilitated flexible work arrangements, which might have impacted the workload and work-related stress that auditors might suffer (Farcane et al., 2022; Robson et al., 2021). Therefore, the consequences of these new arrangements on firms’ organizational context and auditors’ attachment to their jobs and their firms should be analysed in the long term.

Moreover, this study indicates several other opportunities for future research. Big data environment may affect role overload as well as the other role stressors in the audit context. On the one hand, big data analytics may reduce the effect of auditors’ cognitive limitations. However, on the other hand, auditors may experience higher task complexity due to the high volume and variety of information which could lead to higher role stress (Hamdam et al., 2022). Future studies may delve into the effect of the big data environment on auditors’ role stress and job outcomes. In this study, we did not test for the relationship between organizational commitment and job satisfaction, although a high degree of correlation between both variables was found. Although there is greater evidence that job satisfaction is a predecessor of organizational commitment than vice versa, the causal precedence of organizational commitment and job satisfaction has long been a matter of debate. We believe that studies specific to the audit context that develop a causal model of these variables would be of great interest not only to researchers but also to audit firms, as enhancing positive job attitudes could be decisive in avoiding high turnover rates.

Previous research (Eisenberger et al., 1997) has found that in the relationship between favourable job conditions and POS, employees distinguish between those conditions under the organization’s control and those conditions that are beyond the employers’ freedom of action. Audit engagement’s time constraints and subsequent role overload may be perceived as either a market/client-imposed condition or a firm’s/supervisor’s decision. Future research is needed on the influence of employees’ perceptions of audit firms’ control over time budgets on perceived organizational support.