European football clubs and their finances. A systematic literature review

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this systematic literature review is to provide the state of the art, trends and thematic features in the field of accounting and finances of football teams applying the PRISMA guidelines. Seventy-five studies published after the Bosman Act (1995) were included from the most relevant databases: WoS and Scopus. The lines of research included in the analysis were financial performance, sport performance and legislative performance. The synthesis of studies revealed that the scientific output has evolved over time and changes have been detected both on a sporting and scientific level with the introduction of the Financial Fair Play (2012), which is changing the business model of the football industry towards more efficient financial and accounting decision making, which might help the achievement of sporting objectives. Useful policy conclusions such as valuation of intangibles, influence of results on clubs' share prices and directions for future research on football finance are also included in the paper.

Keywords: Football; Finance; Accounting; Financial Fair Play; Literature review.

JEL classification: G000; G010; M400; M410.

Los clubes de fútbol europeos y sus finanzas. Una revisión sistemática de la literatura

RESUMEN

El objetivo de esta revisión bibliográfica sistemática es proporcionar el estado de la cuestión, las tendencias y las características temáticas en el campo de la contabilidad y las finanzas de los equipos de fútbol aplicando las directrices PRISMA. Se incluyeron 75 estudios publicados después de la Ley Bosman (1995) procedentes de las bases de datos más relevantes: WoS y Scopus. Las líneas de investigación incluidas en el análisis fueron el rendimiento financiero, el rendimiento deportivo y el rendimiento legislativo. La síntesis de los estudios reveló que la producción científica ha evolucionado con el tiempo y se han detectado cambios tanto a nivel deportivo como científico con la introducción del Fair Play Financiero (2012), que está cambiando el modelo de negocio de la industria del fútbol hacia una toma de decisiones financieras y contables más eficientes, lo que podría ayudar a la consecución de los objetivos deportivos. También se incluyen en el trabajo conclusiones útiles como la valoración de intangibles, la influencia de los resultados en el precio de las acciones de los clubes y orientaciones para futuras investigaciones sobre las finanzas del fútbol.

Palabras clave: Fútbol; Finanzas; Contabilidad; Juego limpio financiero; Revisión bibliográfica.

Códigos JEL: G000; G010; M400; M410.

1. Introduction

Football is the most popular sport in the world (Giulianotti, 2012). From Rottenberg (1956), Neale (1964), El-Hodiri & Quirk (1971), and Atkinson et al. (1988) onwards, a number of academic studies on the sports industry have emphasized the importance of efficient management for both clubs and competition itself. Since the 1990s, football’s importance has grown beyond the political, social, and cultural spheres and has entered the sphere of finance, developing from a sport into a business (Giulianotti & Robertson, 2004, 2007; Walvin, 2001). Clubs have embarked on a ‘race for cash’, failing to transform revenue into sustainable profits, and even jeopardizing their financial viability (Kennedy, 2013; Storm & Nielsen, 2012). In Spanish football there were serious structural deficiencies (Barajas & Rodríguez, 2010), and similar conclusions have been drawn about the Italian league (Baroncelli & Lago, 2006). Some English clubs at the beginning of the century overspent in order to stay competitive, leading to debt problems (Kuper & Szymanski, 2009). The financial statements of Greek clubs also revealed serious problems (Dimitropoulos, 2010). In 2012, the 235 clubs participating in the European cups spent 15% more than they earned (Galariotis et al., 2018). This situation started to seriously endanger the football industry, not only because of the potential liquidation of clubs, but also because of the loss of competitive balance and the fall in fan interest that could ensue. Television broadcasters need leagues to offer exciting competitions (Goossens et al., 2012). However, in four of the world’s ‘Big Five’ leagues, the number of clubs competing for the top positions was decreasing. Faced with this situation, the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) implemented the Financial Fair Play (FFP) regulations in 2012, in an attempt to save the industry. These regulations impose an annual budget limit based on the resources that each club can generate, with sanctions for clubs that do not comply. The introduction of FFP has brought about a radical change in the football industry, which will be discussed later in this paper.

Despite the importance of the football industry and the various studies carried out, there has not been any review carried out summarizing the current state of research on the finance and accounting of football clubs. Therefore, the aim of this paper is threefold. On one hand, is to analyse the state of knowledge of the academic literature on football finance to see the patterns and trends. On the other hand, is to highlight the importance between sport (specifically football teams) and the finance and accounting issues that have been analysed academically to date by identifying lines of research. Third, by systematically reviewing the mentioned fields of research (football and finance), the goal is to see the results and consequences of the main legal changes affecting football, such as the Bosman act and the rules of the FFP. To our knowledge, this is the first study providing novel empirical evidence on all possible interactions of the key dimensions of accounting, financial, managerial and sporting performance of soccer clubs, identifying the main causes of financial problems that soccer clubs may face, their possible solutions, considering legislations as well, which is of great concern to managers of soccer clubs in the major European leagues.

Conducting a literature review, as Tranfield et al. (2003) point out, is an important part of any research project. This is why, over the last thirty years, academics have tried to improve the review process by synthesizing research in a systematic way, thus avoiding biases and providing it with greater rigour, transparency, and reproducibility. This review was limited to peer-reviewed publications in order to ensure a certain level of quality (Burgess et al., 2006). Consistency between topics and sources was achieved through the careful selection of journals, covering areas of accounting and finance in football.

The article is structured as follows: In the next section, the theoretical framework is set out. This is followed by the methodology. Then, Section 4 will present the results, which are interpreted and evaluated in Section 5, Discussion. Section 6, Conclusions, will summarize the findings of the analysis and outline limitations and future lines of research.

2. State of the art

There is a growing academic and political interest in football clubs,1 and this interest has increased in recent years in the field of accounting and finance. In addition, football has become an important economic sector (Bridgewater, 2010). Sport as a specific field of research is gaining greater recognition within the international academic community (Salgado-Barandela et al., 2017). Football is the most popular sport in the world (Giulianotti, 2012; Matheson, 2003) and is of interest as a field of academic research because it is the only professional sport that is well established in a large number of European countries, which is beneficial for comparison (Schyns et al., 2016).

Since the early 1990s, the economic and financial significance of football has become increasingly clear, to the extent that football can be said to have become a fully fledged business (Baroncelli & Lago, 2006). In the 2018–19 season, the revenues of the top twenty clubs grew by 11%, generating a record €9.3 billion (Deloitte, 2020). Due to their size, the economic behaviour of the top professional sports clubs in the world is attracting growing interest from economists (Gannon et al., 2006; Pinnuck & Potter, 2006; Rohde & Breuer, 2018).

In recent years, the field of study has focused on the so-called ‘Big Five’ leagues: the English Premier League, the Spanish La Liga, the German Bundesliga, the Italian Serie A, and the French Ligue 1. The authors stress that these are the leagues with the highest revenues, the most fans (not only domestically, but around the world too), and that they have the most players participating in the World Cup (Prigge & Tegtmeier, 2019; Ramchandani, 2012; Ramchandani, et al., 2018; Rohde & Breuer, 2016; Solberg & Haugen, 2010). All of these studies focus on men’s football, as women’s football does not yet have the same social and economic impact.

Soccer was first developed in Europe, and most of its history is a European story (Szymanski, 2014). However, it is worth noting other "young" growing leagues, such as Major League Soccer (MLS) with a market value of 951.82 M€ (Transfermarkt, 2022a). It was born in 1996 and it is now the highest level of professional association soccer in the United States and Canada. It is collectively run by franchises and unlike the 5 major leagues, there are no governing organs to oversee it (Peeters & Szymanski, 2014), being a closed league with no promotion or relegation (Hoehn, 2006). Players are contracted by the MLS and not the franchises themselves, with the result that the MLS is in charge of stipulating salary caps (Goddard & Sloane, 2014). The lack of popularity generates TV contract revenues below the rest of other US sports leagues and the major leagues in Europe (Jewell, 2014). Other example is the Chinese Professional Football League (Chinese Super league) created in 1992. The ownership of the clubs (mainly sports administrations and local governments) began to pass into the hands of private investors becoming a hybrid between the traditional centralized control of the government and the governance system of the European context, occurring in 2004 the beginnings of market liberalization (Amara et al., 2005). In 2016, a project was initiated that has attracted the attention of soccer fans around the world due to millionaire investments attracting superstar players, aiming to create a leading soccer team in Asia by 2030 and become a soccer superpower by 2050 (Lemus & Valderrey, 2020). It currently has a market value of 154.94 M€ (Transfermarkt, 2022b). Finally, it is worth mentioning the UAE Pro League, organized by the United Arab Emirates Football Federation with a market value of 217.86 M€ (Transfermarkt, 2022c). All these leagues are still far from the Spanish league, with a market value of 4.94 billion € (Transfermarkt, 2022d).

With the rise in football’s popularity and economic clout, management was pursuing of maximizing results, which lead to financial problems. This situation of financial imbalance began to attract the attention of public bodies in several countries which, seeking to reverse this situation, implemented respective legislations (Italy in 1981, followed by Germany, England, and France). In the case of Spain, this was done with Act 10/1990, of 15 October, on Sport. Despite the aforementioned legislations, debts continued to rise, and they were further exacerbated by the Bosman ruling. In December 1995, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruled that the restriction on the transfer of out-of-contract players was contrary to the provisions of the European Economic Community (EEC) and therefore null and void. Following the ruling, out-of-contract players could freely move from one team to another as long as both teams were resident in the EEC. The Bosman ruling was expected to reduce clubs’ investment in football talent (Antonioni & Cubbin, 2000). However, by enabling the free movement of players with European nationality within the EEC, it had the opposite effect, as we will discuss later in this article, as clubs embarked on a race to sign top players result on serious financial problems (Ascari & Gagnepain, 2007; Barajas & Rodríguez, 2010; Solberg & Haugen, 2010).

This race, and also the soft budget constraints of many clubs, encouraged intense risk-taking and even debt-accumulating. So, good management practices most of the time were crowded out, and instead they encouraged wage and transfer fees inflation (Storm & Nielsen, 2012; Dimitropoulos & Scafarto, 2021). Only a few clubs could afford continued losses, due to overspending on playing talent (Müller et al., 2012). All of the above led that the most common practice of financing was through high leverage debt, with low levels of ROA (Barajas & Rodríguez, 2010, 2014; Dimitropoulos, 2014; Dimitropoulos & Koumanakos, 2015). These insolvency problems were detected in the sector of the whole European soccer (Dimitropoulos & Scafarto, 2021; Szymanski & Weimar, 2019). European football includes a string of clubs with significantly loss-making business models that in “normal” industries would fall into bankruptcy (Müller et al., 2012). In the Spanish case, the situation was critical in the 2010-2011 season when nearly 30 clubs were in or about to enter insolvency proceedings (Gómez, 2017).

Against this practice, UEFA introduced the FFP in 2010. However, the first financial statements considered in UEFA’s assessment are those of the year 2011-12, which is a set of rules that limits the spending of each club according to the resources they are able to generate and that forces the clubs to restore sound financial management. The aim is to ensure that financial efficiency becomes a determining factor in organisational success (Barros et al., 2014) and prevent clubs from having to rely on wealthy individuals to continually cover their losses (Müller et al., 2012). UEFA supervises and executes financial control and has the ability to impose sanctions (Morrow, 2014). It was not until the 2011–12 season, with the arrival of FFP, that clubs began to ‘clean up’ their finances (Birkhäuser et al., 2019; Ghio et al., 2019; Terrien et al., 2017).

Despite the importance of these regulations and the paradigm shift they heralded, there is no academic consensus on their consequences for European football clubs, especially those in the ‘Big Five’ leagues. Our paper addresses this legislative issue, together with the Bosman ruling, in the third research question.

This SLR uses the PRISMA standard, which is one of the most widely used standards for systematic reviews and meta-analyses in business studies. The SLR is a versatile approach, adopted in recent studies published in high-quality academic journals on various research topics, such as innovation and entrepreneurial learning (Adams et al., 2015; Wang & Chugh, 2014), accounting (Licerán-Gutiérrez & Cano-Rodríguez, 2019), and sports economics (Sánchez & Castellanos, 2012). There have been reviews on football (Pratas et al., 2018), football and management (Fort, 2015), and football and talent (Sarmento et al., 2018). Regarding works dealing with team sports and finance, we found only Garner et al. (2016). However, no reviews have been found that deal with the subject of football and finance.

This article presents the first mapping of the entire field of football accounting and finance of nowadays, presenting its structure, evolution, and trends. Our paper identifies considerable differences between the different subfields detected such as the most common topics or general and specific objectives in each subfield.

3. Methodology

This article is based on a SLR of qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods, and conceptual studies, identified in economics, accounting, and finance journals using the WoS and Scopus databases to ensure consistency across topics. The review followed the PRISMA systematic review and meta-analysis guidelines to ensure its quality and to allow for duplication of the study. The PRISMA standard is a set of evidence-based elements, consisting of a 27-item checklist and a four-phase flowchart that ensures the quality of the review. The main advantages of this method are that it provides a structured, repeatable and scientific process to synthesize existing information in a rigorous and objective process (Denyer & Tranfield 2009; Núñez-Merino et al., 2020; Tranfield et al., 2003). The purpose of this study is to provide a systematic and high-quality review of the extensive research in the field of the accounting and finance of the ‘Big Five’ football leagues: the English Premier League, the Spanish La Liga, the German Bundesliga, the Italian Serie A, and the French Ligue 1.

Although the field of European public limited sports companies and sports clubs is not very broad compared to other sectors, it was not an easy task to restrict the search to the concept of men’s football teams. For example, there is a semantic point of confusion (Xu et al., 2007): the word ‘football’ refers to one sport in Europe and a different one in countries such as the United States, where ‘soccer’ is used to refer to what we call ‘football’ on the old continent. This results in divergent definitions (Bhamu & Sangwan, 2014). Therefore, in this study, when we talk about football, we are referring to European football (or soccer in the United States) and not American football. We have excluded women’s football on the grounds that it does not currently have the same following and impact as men’s football.

3.1. Formulation of the research question

This literature review will attempt to answer the following research questions (RQs):

RQ-I: Are there any trends and patterns in the football club finance literature?

RQ-II: What are the main lines of research developed to date?

RQ-III: From a legislative point of view, are there any trends in the football club finance literature that respond to specific legislations?

3.2. Identification of articles

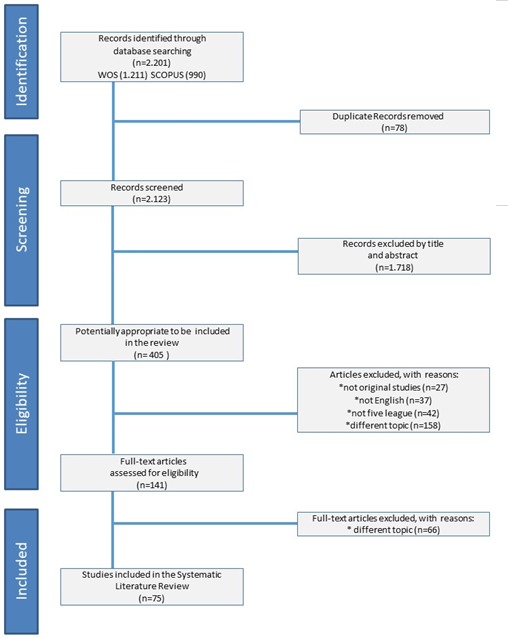

The steps were as follows: identify articles in order to create an initial database, then eliminate previously undetected unrelated articles, thus creating the comprehensive database, and, finally, analyse these articles. The process of literature search and study selection is detailed below and is shown in the PRISMA flowchart in Figure 1.

The first step (Figure 1) was to construct a database of articles that provides an overview of the main characteristics of the football club literature, used to extract data for analysis and further consideration. With this aim in mind, we selected various databases that included studies in the area of social sciences and law before proceeding with the search strategy. A search was carried out in the following databases related to the subject of study: Scopus and Web of Science.2 By choosing these databases, we were able to guarantee the quality of the selected works, given that football is a very common and current research topic. However, this study was undertaken from an academic perspective in the field of accounting and finance, which had never been done before. The search period considered was from 1955 (first article found) to 31 December 2019, using logical sequences combining keywords and Boolean operators. The resulting search string (Table 1) was: ‘(football OR soccer) AND (account* or financ*)’. The keywords used in these search strings were refined through multiple pilot tests in various databases, in order to try to avoid false positives or false negatives and to ensure the identification of relevant documents (Denyer & Tranfield, 2009; Durach et al., 2017).

In Web of Science and Scopus, the limited areas of study were only slightly different since the databases operate in largely the same way. The decision was made to include fields (i.e., to limit) rather than to exclude them, because, according to authors such as Núñez-Merino et al. (2020), this is the correct methodology to apply in order to avoid excluding relevant articles unnecessarily. Areas that were clearly not related to the subject of the study were not considered. For both databases, ‘article’ and ‘reviews’ were considered as document types. Following the first search, we found a total of 2,201 published articles, which were exported to the bibliographic manager Refworks, which found 78 duplicate papers that were subsequently removed. In this way, the first step of the PRISMA guidelines, ‘identification’, was completed.

Table 1. Search Words and Search Strings

| Database | Search Strategy | Records |

|---|---|---|

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY ( ( football OR soccer ) AND ( account* OR financ* ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( SUBJAREA , "SOCI" ) OR LIMIT-TO ( SUBJAREA , "BUSI" ) OR LIMIT-TO ( SUBJAREA , "ECON" ) OR LIMIT-TO ( SUBJAREA , "DECI" ) OR LIMIT-TO ( SUBJAREA , "MATH" ) OR LIMIT-TO ( SUBJAREA , "MULT" ) OR LIMIT-TO ( SUBJAREA , "Undefined" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( DOCTYPE , "ar" ) OR LIMIT-TO ( DOCTYPE , "re" ) ) AND ( EXCLUDE ( PUBYEAR , 2020 ) ) | 990 |

| Web of science | ((football OR soccer) AND (account* OR financ*))Refined by: CATEGORIES OF WEB OF SCIENCE: ( SPORT SCIENCES OR POLITICAL SCIENCE OR ECONOMICS OR MANAGEMENT OR BUSINESS FINANCE OR STATISTICS PROBABILITY OR BUSINESS OR SOCIAL SCIENCES INTERDISCIPLINARY OR LAW OR MULTIDISCIPLINARY SCIENCES OR PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION OR OPERATIONS RESEARCH MANAGEMENT SCIENCE OR MATHEMATICS INTERDISCIPLINARY APPLICATIONS OR SOCIAL SCIENCES MATHEMATICAL METHODS OR SOCIAL ISSUES ) AND TYPES OF DOCUMENTS: ( ARTICLE OR REVIEW ) AND [excluding] YEARS OF PUBLICATION: ( 2020 ) Time period: All years. Indices: SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, AyHCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC. | 1211 |

3.3. Article selection or screening

In this step, only the titles and ab of 2123 articles were reviewed to confirm compliance with the established search criteria by first glance (Denyer & Tranfield 2009; Núñez-Merino et al., 2020 Thomé et al., 2016). After finishing the screening, 1718 articles were eliminated. There were 3 main reasons. The first reason for the elimination was due to the gender of the manuscript, including 28 book chapters, which were not detected by the bibliographic manager despite setting ‘article’ and ‘reviews’ as document types. The second reason was the field of discipline, including 1608 articles related to disciplines such as medicine, other sports, women’s football, refereeing, university football, violence in sports, media, gender, gambling, ethics, technology, the effects of player migration etc. The third reason was the duplicates (82 articles). So there are 405 articles remaining.

3.4. Eligibility

The eligibility process follows the screening. Remember, during the screening only the titles and the abstracts were read. And during the process of the eligibility is when the reading of the sections of the analysis and results happened and the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied (Table 2).

3.4.1. Inclusion criteria

The proposed criteria are summarized in Table 2 and were developed as follows: for ‘methodological’ criteria, qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods, and conceptual studies were included. The second criteria, ‘languages’: English was chosen as an inclusion criterion because it is the language in which most academic articles are published. The next inclusion criterion refers to articles that deal with the ‘Big Five’ leagues, namely, the English Premier League, the Spanish La Liga, the German Bundesliga, the Italian Serie A, and the French Ligue 1, which, as highlighted earlier in this article, are the biggest leagues in the world. The inclusion criteria referring to the ‘subject matter’ of the papers were as follows: Studies dealing with ‘the level of efficiency of the ‘Big Five’ leagues from a financial and/or accounting point of view’, studies on ‘Financial Fair Play (FFP)’, and articles on ‘financial and/or sporting balance’ were included. As were articles dealing with ‘ownership structure and corporate governance of football clubs and their influence on sporting results’, articles dealing with ‘football clubs’ financial performance, insolvency, crises, financial problems, solvency, successes, and/or predictions’, and articles dealing with the ‘accounting and/or valuation of any balance sheet items of football clubs’. Finally, articles whose ‘analysis is carried out on strictly financial and/or accounting inputs or outputs’ were also included.

3.4.2. Exclusion criteria

In the search query we mainly worked with inclusion criteria and the only exclusion we applied was to exclude publications later than 2019 during the data collection not all publications for 2020 were available. By applying exclusion criteria mainly during the eligibility, we could avoid losing articles due to systematic errors caused by incorrectly placed metatags and tags. So, at this step the followings were excluded: papers not written in English, papers not related to the ‘Big Five’ leagues, papers that do not use primary data are excluded, thus eliminating papers such as systematic reviews and meta-analyses, those topics that are not strictly related to the object of study of the paper (but somewhere in the index they used metatags and tags, which were included in the search query and neither during the screening they seemed to contain significantly different disciplines and/or studies).

Table 2 shows the exclusion criteria and the reasons for the 264 eliminations. There were 4 main reasons. The first reason of elimination was not being an ‘original study’ or not using primary data in their analyses (27 papers were eliminated). The second reason of exclusion was that the articles were not written in English, except the abstract (37 articles were eliminated). The third reason was to eliminate articles whose subject matter was not related to the ‘Big Five’ leagues (42 articles were eliminated). The fourth reason was of containing different topics, which is not for the interest of this study (158 papers were excluded). These articles had the subject matter dealing with legislation for lawyers (11 articles), articles about supporters or fans (27 articles), sports marketing (37 studies), articles relating to mega-events such as the World Cup and the Olympics (40 articles). And finally, in case of 43 articles were not found that the word ‘accounting’ was understood as the discipline of studying, measuring, and analysing the assets and financial situation of a company or organization, and ‘finance’ as the study of the raising and management of money and capital, i.e., financial resources.

3.5. Included

Subsequently, a full and thorough reading of the remaining 141 articles was performed to reach the fourth step of the PRISMA guidelines: ‘included’. This led us to discard 66 studies that were clearly not related to the research question. After the application of these criteria, we arrived at the final selection of the articles to be included in the systematic literature review, with a total of 75. The selection of the articles was carried out jointly by the authors in an attempt to eliminate any researcher bias. At this stage, discrepancies were discussed until a high level of agreement was reached (Okoli & Schabram, 2010; Thomé et al., 2016).

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria. Numbers of excludes papers are in brackets

| INCLUSION CRITERIA | EXCLUSION CRITERIA (number of exclusions) | |

|---|---|---|

| METHODS | Qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods, and conceptual studies | Systematic reviews and meta-analyses (27) |

| LANGUAGES | Articles written in English | Articles not written in English (37) |

| LEAGUES | ‘Big Five’ leagues | Leagues other than the ‘Big Five’ (42) |

| SUBJECT MATTER | Efficiency of the ‘Big Five’ leagues | Legislation (11) |

| Financial Fair Play (FFP) | Supporters/fans (27) | |

| Financial and sporting balance | Sports marketing (37) | |

| Ownership structure/corporate governance | Mega-events (40) | |

| Financial performance | Others not accounting and/or finance (43) | |

| Accounting and/or valuation of football clubs | ||

| Strictly financial and/or accounting inputs or outputs |

3.6. Analysis

In this phase, following the methodology proposed by Núñez-Merino et al. (2020), we reviewed and analysed each of the 75 selected articles. After the selection of the studies, we carefully read the full articles to find and organize the data according to the classification variables, such as: ‘year of publication’, ‘journal’, ‘authors’, ‘database’, ‘topic’, ‘objective’, ‘methodology’, ‘contributions’, ‘country of research’, ‘conclusions’, ‘lines of research’, and ‘citations’ of each of the collected articles.

Figure A1. Evolution Over Time of Sector Leverage Ratios

Source: own elaboration.

4. Results

The search yielded a total of 2201 articles published between 1956 and 2019, and ultimately resulted in 75 articles3 for analysis in order to answer the research questions. The meticulously selected articles met the established criteria and were grouped into subgroups or lines of research. In this way, we were able to identify categories, trends, and whether any of these trends could be seen as a response to the implementation of legislation. What follows is a descriptive analysis of the literature on the accounting and finance of football teams in the ‘Big Five’ leagues. The findings for each of the identified lines and sub-lines are presented and analysed.

4.1. RQ-I: Trends and patterns

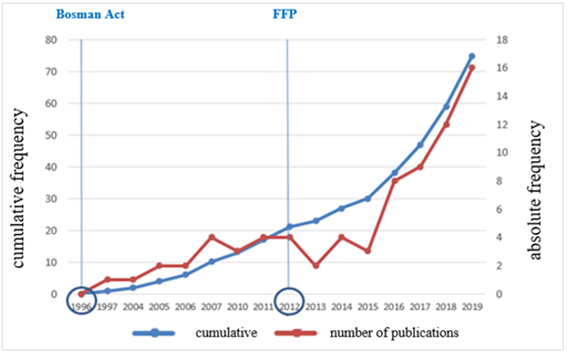

In relation to the first research question, Figure 2 shows the research output by year of publication between 1997 and 2019, the total number of articles published each year, and the cumulative frequency. The graph shows a positive trend in financial studies of football clubs. There is an upward trend in the number of articles included in the SLR. The first article of the review dates back to 1997, one year after the Bosman ruling came into force. Since the FFP regulations were implemented, 77.33% of the articles in the review have mentioned this piece of legislation, so there appear to be patterns in the academic literature.

Figure 2. Evolution of the scientific production of the SLR

Source: own elaboration.

Table 3 indicates the 11 journals with two or more publications. These journals account for 52.00% of the total number of papers collected in the review. The three journals with the highest output are Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, with 7 articles; International Journal of Sport Finance, with 6; and Journal of Sports Economics, with 5.

In order to continue answering the first research question, we present those authors who stand out from the rest. Table 4 shows those with the highest research output and number of citations. The name(s) of the author(s) with the most publications included in the review, their citations, and the respective percentages of the total are shown. The most productive author, Dimitropoulos, P., has a total of 9 publications and is cited 59 times. The authors who appear in the table account for 76.80% of the citations and 54.67% of the total number of articles included in the review. The most cited article (160), ‘The English Football Industry: Profit, Performance and Industrial Structure’, is by Szymanski & Smith (1997).

Table 3. Classification by journals

| Journals (name/ISSN) | Number of papers | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal ( 20426798 print, 2042-678X on-line) | 7 | 9,33% |

| International Journal of Sport Finance (1558-6235 print; 1930-076X on-line) | 6 | 8,00% |

| Journal of Sports Economics (1527-0025 print; 1552-7794 on-line) | 5 | 6,67% |

| International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing (1475-8962 print;1740-2808 web) | 4 | 5,33% |

| European Sport Management Quarterly (16184742 print; 1746031X on-line) | 3 | 4,00% |

| International Journal of Financial Studies (2227-7072) | 3 | 4,00% |

| Scottish Journal of Political Economy (1467-9485) | 3 | 4,00% |

| Applied Economics (0003-6846 print; 1466-4283 on line) | 2 | 2,67% |

| PLoS ONE (1932-6203) | 2 | 2,67% |

| Soccer and Society (1466-0970 print, 1743-9590 on-line) | 2 | 2,67% |

| Team Performance Management (1352-7592) | 2 | 2,67% |

| Others with one article | 36 | 48,00% |

| Total | 75 | 100,00% |

Table 4. Production by authors, citations and publications

| Author | Papers | Citations | % Papers | % Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimitropoulos, P. | 9 | 59 | 12,00% | 5,07% |

| Wilson, R., Pumley, D., Ramchandani, G. | 6 | 94 | 8,00% | 8,08% |

| Plumley, D. | 1 | 8 | 1,33% | 0,69% |

| Ramchandani, G. | 1 | 20 | 1,33% | 1,72% |

| Szymanski, S. | 4 | 194 | 5,33% | 16,67% |

| Barros, C.P., Leach, S. | 3 | 184 | 4,00% | 15,81% |

| Barros, C.P. | 1 | 2 | 1,33% | 0,17% |

| Bosman, A. | 5 | 75 | 6,67% | 6,44% |

| Barajas, A. | 4 | 75 | 5,33% | 6,44% |

| Morrow, S. | 3 | 66 | 4,00% | 5,67% |

| Rodríguez, P. | 2 | 73 | 2,67% | 6,27% |

| Gerrard, B. | 2 | 44 | 2,67% | 3,78% |

| Others with one article | 34 | 270 | 45,33% | 23,20% |

| Total | 75 | 1164 | 100,00% | 100,00% |

Table 5 shows the most frequently used methodologies, with quantitative models featuring most often, in 72% of the articles. The most commonly used quantitative model is regression analysis, accounting for 50.67%. Qualitative models make up 4%, and 24% of the articles used mixed methods.

Table 5. Classification according to methodology used

| Methodology | nº | % |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | 54 | 72,00 |

| Regressions | 38 | 50,67 |

| Others | 16 | 21,33 |

| Qualitative Models | 3 | 4,00 |

| Interviews | 1 | 1,33 |

| Case studies | 2 | 2,67 |

| Mixed | 18 | 24 |

| Total | 75 | 100 |

4.2. RQ-II: Lines of research

The articles were classified in order to respond to the second research question, ‘main lines of research developed until 2019’. Table 6 shows the thematic areas, according to the objective, purpose, and/or general conclusions of the SLR. The main lines of research identified are ‘Financial Measures’, with 35 papers, ‘Sporting Measures’, with 24 papers, and ‘Legislative Measures’, with 16 papers. All three lines of research analyse the effects of FFP on football clubs.

The articles were then grouped into sub-lines of research. The content analysis was then developed further by explaining the general conclusions of the authors by the thematic areas, as grouped in Table 6, Classification of the articles.

Table 6. Classification of papers

| Line | Sub-lines | nº Papers | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Measures (35) | Financial performance | 13 | 17,33% | 46,66% |

| Ownership structure | 10 | 13,33% | ||

| Predictive models | 2 | 2,67% | ||

| Intangibles | 4 | 5,33% | ||

| Share prices | 6 | 8,00% | ||

| Sporting Measures (24) | Competitive balance | 9 | 12,00% | 32,00% |

| League efficiency | 12 | 16,00% | ||

| Wage and transfer spending | 3 | 4,00% | ||

| Legal Measures (16) | FFP | 16 | 21,34% | 21,34% |

| Total | 75 | 100% |

4.2.1. RQ-II (Line 1): Financial Measures

The ‘Financial Measures’ line of research includes articles whose objective, purpose, and/or general conclusions deal with the reasons, variables, implications, and effects that underlie the financial situation of football clubs in the ‘Big Five’ leagues. Five sub-lines were identified: ‘financial performance’, with an output of 17.33%; ‘ownership structure’, with 13.33%; ‘predictive models’, with 2.67%; ‘intangibles’, with 5.33%; and ‘share prices’, with 8.00%.

Financial performance

The ‘financial performance’ sub-line shows the financial situation of football clubs in the ‘Big Five’ leagues, together with any causes and possible solutions. In European football, sporting objectives have taken precedence over organizational or financial objectives (Dimitropoulos & Koumanakos, 2015; Solberg & Haugen, 2010; Szymanski & Smith, 1997; Vrooman, 2007) which could explain the following findings:

Most of the clubs in the ‘Big Five’ leagues have faced financial problems (Ascari & Gagnepain, 2007; Barajas & Rodríguez, 2010, 2014; Dimitropoulos & Koumanakos, 2015; Solberg & Haugen, 2010; Szymanski & Smith, 1997; Vrooman, 2007). especially after the Bosman ruling (Ascari & Gagnepain, 2007; Solberg & Haugen, 2010; Szymanski & Smith, 1997; Vrooman, 2007). The main cause of this financial instability is the high salaries being paid to build up the clubs’ squads, in a race to sign the top players (Ascari & Gagnepain, 2007; Barajas & Rodríguez, 2010, 2014; Dimitropoulos & Koumanakos, 2015; Solberg & Haugen, 2010; Szymanski & Smith, 1997; Vrooman, 2007). Owners who do not adapt to risk and who increase their spending in search of talent are the main cause of financial collapse in European clubs (Vrooman, 2007). This financial instability coincides with the increase in revenues from TV rights and other sources, resulting in a lack of correlation between revenue and expenditure (Ascari & Gagnepain, 2007, Solberg & Haugen, 2010). Clubs also have higher wage costs if they participate in European competitions (Ascari & Gagnepain, 2007).

Regardless of financial discipline, a series of negative sporting shocks can lead to insolvency within the ‘Big Five’ leagues (Szymanski, 2017). In the English league, from 1982 to 2010, it has been shown that finishing mid-table or in the bottom half is associated with losses, while finishing near the top is associated with profits (Szymanski & Smith, 1997). One of the main causes of insolvency is the system of promotion and relegation (Szymanski & Weimar, 2019). Another causal factor of the serious financial problems that have existed for decades in European football, and especially in the ‘Big Five’ leagues, that was noted by the authors is that the most common way of financing football clubs is through debt (Barajas & Rodríguez, 2010, 2014; Dimitropoulos & Koumanakos, 2015) with high leverage, weak cash flow generation capacity, and low levels of ROA and ROE (Dimitropoulos & Koumanakos, 2015).

Clubs in the ‘Big Five’ leagues with private owners have been found to be in poorer financial health than publicly listed clubs (Rohde & Breuer, 2016). Finally, it is worth mentioning that increased regulations whose sanctions can lead to relegation cause greater financial problems (Scelles et al., 2018).

The authors’ proposed solutions to the financial difficulties are as follows:

Stronger legislation on balance sheets (Ascari & Gagnepain, 2007).

NBA (or European Super League) type closed leagues (Ascari & Gagnepain, 2007, Szymanski, 2017; Vrooman, 2007).

Necessary reduction of current liabilities (Barajas & Rodríguez, 2014).

Introduction of a salary cap, with lower salaries and additional bonuses (Barajas & Rodríguez, 2010; Solberg & Haugen, 2010; Szymanski, 2017), although this would be difficult to implement as the risk would be passed on to the players (Solberg & Haugen, 2010).

Mechanisms linking expenditure and revenue (Solberg & Haugen, 2010).

Necessary increase in revenue (Barajas & Rodríguez, 2014), which in turn is influenced by better performance in domestic competitions (Ascari & Gagnepain, 2007, Rohde & Breuer, 2016, Szymanski, 2017) and participation in European competitions (Barajas & Rodríguez, 2010; Dimitropoulos & Koumanakos, 2015).

Increased investment in intangibles, such as player talent, coaches, doctors, and management, which helps improve financial profitability, as it increases future profits in merchandising, ticket sales, sponsorship, and TV rights (Dimitropoulos & Koumanakos, 2015; Mnzava, 2013).

A more professional club structure, which tends to coincide with a lower risk of accumulating debts that could lead to non-payment of wages and, by extension, insolvency (Barajas & Rodríguez, 2014, Hammerschmidt et al., 2019; Scelles et al., 2018).

Coordination strategies between all competing clubs, which can lead to positive changes in the industry (Szymanski & Smith, 1997), such as a more equitable distribution of TV rights (Szymanski & Smith, 1997; Vrooman, 2007).

Regarding the relationship between financial performance and sporting performance, the authors indicate that ‘financial muscle’ affects the sporting performance or success of clubs in the ‘Big Five’ leagues. More specifically, they point to a direct relationship between the level of salaries and/or investment in players and sporting success (Hammerschmidt et al., 2019; Mnzava, 2013; Rohde & Breuer, 2016; Szymanski, 2017). The relationship between player investment and sporting success, as well as between team performance and revenue, is relatively stable and predictable (Szymanski, 2017). A direct relationship between profit margin (margin/cost) and sporting performance is also observed, with clubs at the top of the table making a profit, while finishing mid-table or in the bottom half is associated with absolute losses (Szymanski & Smith, 1997). Financial success is positively affected by national, international, and commercial sporting success (Dimitropoulos & Koumanakos, 2015; Rohde & Breuer, 2016).

Ownership structure

The second sub-line, ‘ownership structure’, groups together those articles that deal with the influence of ownership structure on the financial performance of football clubs.

There is a non-linear relationship between ownership structure and financial performance (inverted U-shaped curve) (Acero et al., 2017). In organizations with dispersed ownership, an increase in the level of ownership concentration has a positive effect on financial performance (Acero et al., 2017; Dimitropoulos, 2014; Ruta et al., 2019). However, too much concentration has a negative effect (Acero et al., 2017; Sánchez et al., 2017; Rohde & Breuer, 2018; Ruta et al., 2019; Scafarto & Dimitropoulos, 2018) due to the expropriation of minority shareholders (Acero et al., 2017; Scafarto & Dimitropoulos, 2018), especially if there is separation between control and ownership, as agency problems arise (Sánchez et al., 2017;). In the same vein, corporate governance with independence between the CEO and the president improves financial performance (Dimitropoulos, 2011; Dimitropoulos, 2014; Ruta et al., 2019; Scafarto & Dimitropoulos, 2018; Ward & Hines, 2017). However, this division in corporate governance has little financial impact for clubs with highly concentrated ownership (Ruta et al., 2019). The nationality of the investors also affects clubs’ financial efficiency, as clubs with a majority of national owners tend to have greater financial efficiency (Sánchez et al., 2017; Rohde & Breuer, 2018; Wilson et al., 2013). Publicly listed clubs have improved financial discipline and performance (Baur & McKeating, 2011; Wilson et al., 2013), but not their sport performance after an IPO (Baur & McKeating, 2011;). In the German Bundesliga, the 50+1 rule provides better financial results (Acero et al., 2017)).

The ownership structure also affects sporting performance. Football teams organized as clubs tend to have better sporting performance than those organized as companies (Sánchez et al., 2017). Previously, we mentioned that greater ownership concentration can lead to financial instability, but these clubs tend to achieve better sporting results (Ruta et al., 2019; Scafarto & Dimitropoulos, 2018), and the greater the independence between the board and the CEO, the more positively related it is to better sporting performance (Ruta et al., 2019). In order to improve sporting performance, there is a tendency to increase spending on players (Ward & Hines, 2017). Finally, it is worth mentioning that the share price of publicly listed clubs is related to match performance (winning or losing) (Baur & McKeating, 2011).

Predictive models

The sub-line ‘predictive models’ groups the two papers that try to develop a predictive model for the financial difficulties of football clubs. The first paper indicates that clubs that are not in financial trouble have twice as many shareholders, with the model showing that the best predictors of financial problems leading to insolvency are ‘low liquidity’, ‘high leverage’ (total liabilities/total assets), ‘poor financial performance’, and ‘market size’ (not being the biggest club in the city). In addition, the paper stresses the importance of the variables ‘total debt/profitability’ and ‘current liabilities/current assets’, as well as the amount of revenue earned, which is closely related to the ability to repay debt with leeway to invest in players. The leverage variable is directly related to financial difficulties and even insolvency within a period of one or two years. Relegated clubs tend to have more financial problems if they are not the biggest club in their region (Alaminos & Fernández, 2019). The second paper mentions the importance of liquidity and the ‘current assets/short-term debts’ and ‘equity/total assets’ ratios in the bankruptcy of clubs, pointing to lower-than-expected revenues and sporting results as the main cause of bankruptcy (Carin, 2019). Monitoring these ratios is vital in preventing the risk of bankruptcy (Alaminos & Fernández, 2019; Carin, 2019).

Intangibles

The sub-line ‘intangibles’ includes the articles that study the particularities of the valuation of the intangibles of football clubs, i.e., the players that make up the squads.

There is a deficit in international and Spanish accounting standards on players who came through the club’s youth academy, who are not capitalized in their balance sheets due to the lack of reliable values and the non-existence of an active intangible market as a result of the high risk and difficulty of estimating future earnings (Lozano & Gallego, 2011). This work indicates that acquired players are accounted for at acquisition price (market value), and their amortization is calculated according to the duration of the contract, with the value of the transfer rights of acquired players being the most important asset in the balance sheets of football clubs. This results in an undervaluation in the balance sheet of former academy players, and also of many acquired players, leading to cases of players whose market value is much higher than that reflected in the balance sheet. It also indicates that valuations made by an independent valuation panel are much higher than the accounting valuations. Due to this latent undervaluation and the fact that for many clubs the purchase and subsequent sale of players is the main generator of value and means of survival, these authors consider it reasonable that, in order to contribute to a true and fair picture of accounting statements, the option of an independent valuation of intangibles has to be taken into account. The presumption in International Accounting Standards (IAS) that assets acquired in an arm’s-length transaction should be capitalized is challenged (Amir & Livne, 2005).

On the other hand, works on models that try to value players agree that the value of a player is difficult to quantify (Coluccia et al., 2018; Kanyinda et al., 2012). There is debate among academics about the existence of a real market for players, calling for the need to unify a model to account for fair value (reflecting a true picture of accounting statements) (Coluccia et al., 2018). Kanyinda et al. (2012) shows two methods of valuing a footballer and demonstrates that his value (based on career parameters such as injuries) and his marketing value (related to shirt sales, etc.) can be modelled on the basis of options on real assets. Both of these models, applied to the evaluation of certain players, could contribute to a reliable valuation of human assets (close to a fair value) on the balance sheets of football clubs.

Share prices

The second sub-line, ‘share prices’, includes studies of situations or events that affect the share price of football clubs.

There is an asymmetric market relationship/reaction to match results, with post-match returns to losses being significantly negative. Meanwhile, the return to wins, while positive, is close to zero. In other words, losing predicts a club’s share price value in the negative better than winning in the positive (Berkowitz & Depken, 2018; Bernile & Lyandres, 2011; Botoc et al., 2019; Gimet & Montchaud, 2016). The majority of publicly listed European clubs have overvalued shares, which is explained by the fact that the behaviour of investors in the football industry is more irrational, which makes this type of investment attractive for strategic investors, sponsors, and fans, but not for purely financial investors (Prigge & Tegtmeier, 2019). English clubs experienced improved sporting achievement and falling share price values after IPOs, because they used this increased funding to acquire players and pay higher wages in the pursuit of success on the pitch, which led to long-term financial problems (Litvishko et al., 2019).

4.2.2. RQ-II (Line 2): Sporting Measures

Sporting Measures groups together those studies that analyse the financial actions that affect both the competitive balance and the efficiency of the leagues and/or clubs analysed. It was divided into three sub-lines: ‘competitive balance’, with an output of 12.00%; ‘league efficiency’, with 16.00%; and ‘wage and transfer spending’, with a total of 4.00%.

Competitive balance

The first sub-line, ‘competitive balance’, groups the articles on the influence of financial actions on the balance of domestic leagues, whereby greater balance is understood as more clubs having a chance of winning their respective leagues, or a greater number of winners of the leagues studied in a given period.

In the ‘Big Five’ leagues, the lower the financial balance between clubs, the greater the competitive imbalance (Bisceglia et al., 2018; Carreras & Garcia, 2018; Dobson & Goddard, 2004; Gerhards & Mutz, 2017; Plumley et al., 2018; Ramchandani, 2012; Ramchandani et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2018). This economic inequality is conditioned by the revenue earned, the distribution of which is very unequal (Dobson & Goddard, 2004; Gerhards & Mutz, 2017; Plumley & Flint, 2015; Ramchandani, 2012), particularly with regard to TV rights (Bisceglia et al., 2018; Carreras & Garcia, 2018; Plumley et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2018). A fairer distribution of TV rights would help to balance the competition in the ‘Big Five’ leagues, although it could negatively affect the top clubs (Bisceglia et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2018). The authors agree that higher revenues facilitate the acquisition of higher-quality players and promote inequality between clubs. The Bosman ruling increased this competitive imbalance (Dobson & Goddard, 2004; Gerhards & Mutz, 2017).

Although economic theory suggests that a decrease in competitive balance will lead to a fall in fan interest, TV rights revenues are at their highest point. The ‘Big Five’ leagues thus continue to confound economic theory (Ramchandani et al., 2018).

In addition to the distribution of TV rights, the financial imbalance is caused by the revenue earned from participating in European competitions (Plumley et al., 2018) and the increased acquisition of clubs by foreign investors (Plumley et al., 2018; Ramchandani, 2012). The market value of a club is a good predictor of league points won, highlighting its importance in the competitive balance (Gerhards & Mutz, 2017). Paradoxically, clubs from more balanced domestic leagues are less successful in international competitions (Bisceglia et al., 2018; Ramchandani et al., 2018).

The current seeding format of the UEFA Champions League is also a factor that favours historically bigger clubs, as it is geared towards helping these clubs reach the latter stages of the competition, where the distribution of revenue from victories and/or qualification is greater, leading to an imbalance in the competition and, by extension, a reduced number of clubs receiving higher revenues. Again, this influences the domestic competitions by fostering domestic competitive imbalance (Plumley & Flint, 2015; Ramchandani et al., 2018).

Another interesting observation is that FFP seeks to limit spending/investment, and, as a result, clubs that increased their investment prior to its implementation, in an attempt to improve the quality of their squads, have an advantage over the rest (Plumley et al., 2018). After the implementation of FFP, with the exception of the English league, the imbalance has increased in the other four big leagues (Gerhards & Mutz, 2017). The effects of FFP will be analysed in the ‘Legislative Measures’ line of research.

League efficiency

The second sub-line, ‘league efficiency’, groups the 13 articles that deal with the efficiency of clubs and/or leagues, where efficiency is understood as the relationship between spending/investment and sporting performance (Pyatunin et al., 2016).

Football clubs in general have different efficiency scores (Barros & Leach 2006a; Barros & Leach 2007; Barros et al., 2014; Crisci et al., 2019; Guzmán & Morrow, 2007; Miragaia et al., 2019; Plumley et al., 2017; Pyatunin et al., 2016). The skills of the management team are linked to sporting and financial performance in the football market (Barros & Leach, 2006a; Barros & Leach, 2007; Gerrard, 2010; Pantuso, 2017; Pyatunin et al., 2016). Indeed, the key to good financial and sporting performance is to invest in young, cheap players with high potential (Pantuso, 2017).

Sporting and financial success do not always coincide (Barros & Leach, 2007; Barros & Leach 2006a; Barros et al., 2014; Crisci et al., 2019, Pantuso, 2017; Plumley et al., 2017). In many cases financial performance is negatively related to sporting performance (Barros & Leach, 2006a; Barros & Leach 2007; Crisci et al., 2019, Gerrard, 2005; Gerrard, 2010; Guzmán & Morrow, 2007) and many authors indicate that, in general, elite clubs may be less efficient (Barros & Leach, 2006a; Barros & Leach 2007; Gerrard, 2010). Only one study found the contrary, that those of with higher efficiency coefficients were better performers (Miragaia et al., 2019). The most efficient clubs tend to be the richest clubs (Pyatunin et al., 2016), and revenue is also found to be positively related to sporting performance (Gerrard, 2005; Pyatunin et al., 2016). More specifically, clubs that receive the highest TV revenues are the most efficient (Miragaia et al., 2019). On the other hand, publicly listed clubs tend to be the most efficient (Gerrard, 2005). Incidentally, sporting success is found to be one of the main cost drivers (Barros & Leach 2006a; Barros & Leach 2007; Gerrard, 2010), whereby increased spending increases inefficiency if it does not translate into points won (Barros & Leach, 2006a; Barros & Leach 2007, Miragaia et al., 2019).

This sub-line concludes by pointing out the need for further research to clarify the determinants of inefficiency among clubs (Barros & Leach, 2006a; Barros & Leach 2007; Barros & Leach, 2006b; Gerrard, 2010; Plumley et al., 2017).

Wage and transfer spending

The third sub-line of research, ‘wage and transfer spending’, contains three articles that deal with the influence of player spending, both in terms of wages and transfers, on sporting performance (Bucciol et al., 2014; Burdekin & Franklin, 2015; Kulikova & Goshunova, 2016).

There is a lack of consensus in the literature on wage dispersion. It can be observed in the Italian league that wage dispersion has a negative effect on sporting performance. More specifically, multiplying the wage dispersion decreases the probability of winning a match by 6%. This wage dispersion originates as a consequence of differences in players’ skills and talents (Bucciol et al., 2014). Similar findings are observed in the English league, where an increase in spending on player wages has no significant effect on points won for the top clubs, and usually has a negative effect for the remaining clubs (Burdekin & Franklin, 2015). In both leagues, there is a significant positive relationship between transfer spending and points won (Burdekin & Franklin, 2015; Kulikova & Goshunova, 2016). This effect is greater for clubs in the bottom half of the table, due to the fact that the top clubs have a higher level of talent (Burdekin & Franklin, 2015).

For English clubs, higher spending on both wages and transfers increases revenue, but has a negative effect on profits (Burdekin & Franklin, 2015). Thus, optimal investment in players is a key tool for improving a club’s management efficiency, both financially and in sporting terms (Burdekin & Franklin, 2015; Kulikova & Goshunova, 2016). In the quest to improve results on the pitch, English clubs increased spending on both wages and transfers, leading to the introduction of FFP (Burdekin & Franklin, 2015), which we will analyse below.

4.2.3. RQ-II (Line 3): Legal Measures

This line of research includes articles aimed at analysing the implications and effects of FFP. This line has attracted the highest research output since the implementation of FFP in 2012.

The 16 papers agree that the delicate financial situation of the football industry was the trigger for UEFA’s decision to implement budget restrictions and greater financial control through FFP. These regulations were intended to improve clubs’ financial health and to bring balance to both domestic and international competitions. It is worth noting that the clubs in the ‘Big Five’ leagues that have historically been allowed to run larger deficits generated by the signing of more talented players have obtained better results on the pitch, and that this is the main cause of financial difficulties (Drut & Raballand, 2012).

After the implementation of FFP, an improvement in clubs’ finances was observed (Birkhäuser et al., 2019; Dimitropoulos, 2016; Dimitropoulos & Koronios, 2018; Dimitropoulos & Scafarto, 2021; Freestone & Manoli, 2017; Ghio et al., 2019; Terrien et al., 2017), although clubs were still experiencing financial difficulties post-FFP (Dimitropoulos, 2016; Dimitropoulos & Scafarto, 2021, Nicoliello & Zampatti, 2016). Even post-FFP, in the French league, clubs with worse financial results (high debts) tended to obtain better sporting results (Galariotis et al., 2018).

FFP promotes a paradigm shift by moving clubs away from investing in talent (high-quality players) and towards a model of investment cycles in talented young players who are later sold, thus generating additional revenue streams (Dimitropoulos & Scafarto, 2021; Nicoliello & Zampatti, 2016). Therefore, the introduction of FFP should result in improved financial efficiency (Dimitropoulos & Scafarto, 2021; Freestone & Manoli, 2017; Nicoliello & Zampatti, 2016).

The implementation of FFP has led to an increased competitive imbalance in the ‘Big Five’ leagues (Birkhäuser et al., 2019; Madden, 2015; Plumley et al., 2019; Sass, 2016; Terrien et al., 2017). A greater imbalance between rich and poor clubs has been observed, eliminating the possibility for smaller clubs to catch up with bigger clubs, primarily due to the fact that FFP limits the injection of funds (Plumley et al., 2019). The application of FFP would appear to entrench the existing order, benefiting clubs that were able to take advantage of the previous lack of financial regulation in football (Sass, 2016; Madden, 2015). However, the competitive imbalance has been constantly growing since the 1995–96 season due to the financial disparity between clubs, but there is no evidence that FFP regulations have resulted in a decline in competitive balance in the Premier League (Freestone & Manoli, 2017). In fact, the paper ‘insinuates’ that there might be a slight improvement. In the Italian league, FFP has helped to improve the competitive balance, notably by reducing the gap between clubs that participate in European competitions and those that do not (Ghio et al., 2019).

With regard to the effects on the quality of accounting information, an improvement was observed due to stricter control post-FFP (Dimitropoulos & Koronios, 2018). Clubs with low profitability and low cash flows hired high-quality auditors to project an image of financial soundness and thus comply with FFP requirements (Dimitropoulos, 2016; Dimitropoulos et al., 2016). The main effect of FFP in this respect is that the fees of the ‘Big Four’ accounting firms have increased (Mareque et al., 2018). However, one should not lose sight of the difficulty of preventing the use of accounting manipulation to comply with FFP requirements (Dimitropoulos & Koronios, 2018).

The reasons for the negative effects of FFP are as follows: Firstly, the limitation of cash inflows from investors is alluded to as the main driver of the imbalance (Birkhäuser et al., 2019; Dermit-Richard et al., 2019; Madden, 2015; Plumley et al., 2019; Sass, 2016). By limiting spending relative to resources, clubs with less financial muscle have fewer opportunities to acquire more talented players (Plumley et al., 2019; Sass, 2016). Moreover, this limitation is in conflict with the French DNCG (National Direction for Management Control which is the French organisation for the management control of football clubs, focusing on solvency), which allows liquidity injections to avoid the risk of insolvency (Dermit-Richard et al., 2019). The increase in prize money for the winners of European competitions is creating different levels of hierarchy, increasing the competitive imbalance (Birkhäuser et al., 2019).

Deficient regulation brings losses for supporters, owners, and players (Madden, 2015). To reduce these deficiencies, a restructuring of FFP rules is needed (Dermit-Richard et al., 2019; Galariotis et al., 2018; Terrien et al., 2017). More specifically, a new redistribution of revenues is required (Birkhäuser et al., 2019). In terms of individual solutions, the football model should be oriented towards discovering, incorporating, developing, and selling talented young players (Dimitropoulos & Scafarto, 2021; Nicoliello & Zampatti, 2016) attracting new investors with the aim of increasing the capitalization of the club (Nicoliello & Zampatti, 2016) and, last but not least, innovation and new avenues of financing (Plumley et al., 2019).

4.3. RQ-III: Legislation

As for the third research question, there is evidence to suggest that the research output is responding to two specific pieces of legislation. The first article included in this review dates from one year after the ruling of 15 December 1995 by the European Court of Justice, commonly known as the Bosman ruling. As a result of this ruling, the possibility of acquiring players of European nationality without the previous limitations led clubs into a ‘race’ to acquire talent, thereby increasing expenditure and aggravating an already delicate situation (Ascari & Gagnepain, 2007; Burdekin & Franklin, 2015; Coluccia et al., 2018; Dimitropoulos et al., 2016; Dobson & Goddard, 2004; Gerhards & Mutz, 2017; Gerrard, 2010; Madden, 2015; Solberg & Haugen, 2010, Szymanski & Smith, 1997; Szymanski & Weimar, 2019; Vrooman, 2007). This fact is mentioned in one way or another in 16% of the articles analysed. Regarding FFP, as can be seen in Table 7, 21.34% of the articles study its effects on football clubs (Birkhäuser et al., 2019; Dermit-Richard et al., 2019; Dimitropoulos, 2016; Dimitropoulos et al., 2016; Dimitropoulos & Scafarto, 2021; Dimitropoulos & Koronios, 2018; Drut & Raballand, 2012; Freestone & Manoli, 2017; Ghio et al., 2019; Madden, 2015; Mareque et al., 2018; Nicoliello & Zampatti, 2016; Plumley et al., 2019; Sass, 2016; Terrien et al., 2017). However, what is even more striking is that up to 48% of studies mention FFP (Acero et al., 2017; Alaminos & Fernández, 2019; Barajas & Rodríguez, 2014; Burdekin & Franklin, 2015; Dimitropoulos & Koumanakos, 2015; Gerhards & Mutz, 2017; Gimet & Montchaud, 2016; Litvishko et al., 2019; Miragaia et al., 2019; Pantuso, 2017; Plumley et al., 2018; Plumley et al., 2017; Ramchandani et al., 2018; Rohde & Breuer, 2016, 2018; Ruta et al., 2019; Scafarto & Dimitropoulos, 2018; Szymanski, 2017; Szymanski & Weimar, 2019; Wilson et al., 2013). For all these reasons, we understand that the academic evolution of the articles that meet the criteria selected for this review responds, to a certain extent, to these two pieces of legislation.

Table 7. Classification of the papers

5. Discussion

We maintain that this work is original and novel. There are similar reviews, such as Szymanski (2010), which deals with the finances of English football clubs, and Morrow (2013), which focuses on the accounting regulation of football clubs. In the same vein, Szymanski (2014) analyses the new FFP regulations and their deficiencies and implications. Sloane (2015) reviews the economics of professional football from a broader perspective without delving into the financial details, as our article does. Sroka (2020) looks at tax increment financing in American football.4 Our work, then, is the first to carry out a SLR in the field of the accounting and finance of football clubs in the ‘Big Five’ leagues, which confirms the originality and novelty of the results obtained.

What stands out in this new approach is the finding that football clubs, from the 1990s until the introduction of FFP, operated at a loss (Ascari & Gagnepain, 2007; Barajas & Rodríguez, 2010, 2014; Dimitropoulos & Koumanakos, 2015; Scelles et al., 2018; Solberg & Haugen, 2010; Szymanski, 2017; Szymanski & Smith, 1997; Szymanski & Weimar, 2019; Vrooman, 2007), which is in line with previous studies such as Szymanski (2010) and Vöpel (2011). This could be explained by the fact that, in the major European leagues, sporting objectives take precedence over financial or organizational ones (Bisceglia et al., 2018; Burdekin & Franklin, 2015; Dermit-Richard et al., 2019; Dimitropoulos & Koumanakos, 2015; Dimitropoulos & Koronios, 2018; Dobson & Goddard, 2004; Plumley et al., 2017; Prigge & Tegtmeier, 2019; Scafarto & Dimitropoulos, 2018; Solberg & Haugen, 2010; Szymanski, 2017; Szymanski & Smith, 1997, Vrooman, 2007). This financial instability is exacerbated by clubs’ race to sign talented players, especially after the Bosman ruling (Ascari & Gagnepain, 2007, Burdekin & Franklin, 2015; Coluccia et al., 2018; Dimitropoulos et al., 2016, Dobson & Goddard, 2004; Gerhards & Mutz, 2017; Gerrard, 2010; Madden, 2015; Solberg & Haugen, 2010; Szymanski & Smith, 1997; Szymanski & Weimar, 2019; Vrooman, 2007), which is also in line with previous research, including Budzinski & Szymanski (2015). This situation of financial instability put the football industry in serious danger, so much so that several clubs were at clear risk of insolvency. In Spain, before the implementation of FFP, up to 30 first and second division clubs were in insolvency or on the verge of insolvency (Gómez, 2017).

UEFA responded with the implementation of FFP in the 2011–12 season, limiting clubs’ spending relative to the resources they are able to raise. After its implementation, a change has been observed both in the football industry and in the academic literature. There is a consensus among authors regarding the improvement in clubs’ financial situation (Birkhäuser et al., 2019; Dimitropoulos, 2016; Dimitropoulos & Koronios, 2018; Dimitropoulos & Scafarto, 2021; Freestone & Manoli, 2017; Ghio et al., 2019; Terrien et al., 2017). In the content analysis of this SLR, we found open debate as to the sporting implications of FFP. Although FFP was not designed to address the issue of competitive balance (Franck, 2018), after its implementation an increase in competitive imbalance in the ‘Big Five’ leagues was observed by some authors (Birkhäuser et al., 2019; Madden, 2015; Plumley et al., 2018; Plumley et al., 2019; Sass, 2016; Terrien et al., 2017), while others (Freestone & Manoli, 2017; Ghio et al., 2019) considered that the imbalance was actually reduced for the leagues analysed. There is unanimity on the need for the restructuring of FFP (Ascari & Gagnepain, 2007; Galariotis et al., 2018; Terrien et al., 2017).

Another major contribution of this work is the important connection it establishes between financial and sporting success, since financial success is affected by domestic or international success on the pitch (Rohde & Breuer, 2016, Ruta et al., 2019). In addition, the share price value reacts to victories and defeats (Berkowitz & Depken, 2018; Bernile & Lyandres 2011; Botoc et al., 2019). It has also been observed that the higher the investment and or/salary expenditure on players, the better the sporting results (Barajas & Rodríguez, 2010; Barros & Leach, 2007; Dimitropoulos & Koumanakos, 2015; Hammerschmidt et al., 2019; Mnzava, 2013; Szymanski, 2017).

Therefore, in order to improve sporting and financial performance, the authors highlight the need for new forms of financing (Barajas & Rodríguez, 2014; Plumley et al., 2019), financial innovation (Dimitropoulos & Scafarto, 2021; Nicoliello & Zampatti, 2016; Plumley et al., 2019), and investment in talented young players who could potentially be sold for a profit down the line (Dimitropoulos & Scafarto, 2021; Nicoliello & Zampatti, 2016; Pantuso, 2017). In the same vein, the possibility of creating a system of closed leagues (inspired by the NBA model) as a solution to the above-mentioned inequality would increase revenue streams and thus further boost the European football industry. In fact, on 19 April 2021, Florentino Pérez, the president of Real Madrid, announced the creation of the European Super League, in order to, in his words, ‘save football’. However, following pressure from UEFA, this project seems to be on standby for the moment.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we conducted a SLR of existing studies using the PRISMA recommendations, providing an overview of the current state of research, and the key aspects and themes of finance and accounting issues in football. The purpose of this paper is not to offer a definitive answer as to which studies are most adequate, but simply to describe the state of the art on the subject.

The considerable number of studies reviewed resulted in a final total of 75 articles, which have provided answers to the three research questions outlined above. The trends and patterns of research output have been observed, allowing the identification of the most common journals, authors, and topics, thus answering the first research question. We note from our findings that there has been growing academic interest in the subject in recent years. 48% of the studies mention UEFA’s FFP legislation, and this is the main subject of study in 21.34% of the studies.

With regard to the second research question, the categories of the articles were identified and classified into lines and sub-lines of research, as shown in Figure 3 and Tables 6 and 7. The academic research undertaken pre-FFP focused mainly on the factors that had led to the delicate financial situation that European football clubs found themselves in at the time. According to the SLR, this was driven by the neglect of financial objectives in pursuit of achievements on the pitch (Szymanski & Smith, 1997), as well as a lack of legislation, which led managers to overspend to sign high-quality players or, as some define it, to ‘invest in talent’ (Ascari & Gagnepain, 2007).

With the introduction of FFP regulations in 2011–12, an improvement in the financial performance of football clubs was observed across Europe, mainly in the ‘Big Five’ leagues. However, some authors point to possible financial manipulation in order to comply with the regulations. It is worth mentioning that there is a consensus regarding the financial improvement of the football industry after the implementation of FFP. However, there are disagreements regarding its undesired effects, such as the increase of a competitive imbalance that could put domestic leagues at risk. Further research is therefore needed to reach definitive conclusions.

Special mention should be made of the deficit in international and Spanish accounting standards on former academy players (Lozano & Gallego, 2011) in the sub-line on evaluating the ‘intangibles’ of a club’s players, both those who were acquired and above all those who came through the youth academy. According to the literature reviewed, these players should be valued at market price and not at acquisition cost, as they are currently capitalized. According to the authors, this would reflect a true and fair view of the accounting statements, which would modify the spending limits imposed by UEFA through FFP, and would increase the possibility of investment and expenditure in a quest to improve the financial results and, by extension, the sporting results of certain clubs.

Finally, with regard to the third research question, we conclude that there is evidence to believe that the Bosman ruling and the introduction of FFP have together brought about changes in both the financial and academic landscape of the football industry in Europe.

Implications of this study can be identified, firstly, for clubs’ managers themselves. The literature reviewed indicates that it is necessary to improve financial efficiency to be able to continue acquiring talented players to maximize sporting objectives and comply with FFP. The constant search for innovation of new sources of funding should be a primary focus, such as the acquisition of young and low-cost players with projection and the internal development of junior players, who can be sold later and increase the salary limit set by the FFP. This would allow the acquisition of talented players to increase both the quality of the soccer staff and the number of followers, sponsors, TV rights, etc. Regarding league regulators, the document shows that the application of FFP has radically changed the financial situation of European soccer towards more sustainable business models, although they should consider the possibility of possible cases of financial doping in order to comply with the requirements of the law itself. European league managers should not neglect the possible negative consequences that FFP could have triggered, such as the possible loss of balance in national leagues that could decrease the demand for the product. They should also consider the possible negative impact of a European super league on national leagues and the current European competitions.

This review is not without its limitations. The first relates to the search for articles. Two databases were used for the literature review, and non-indexed articles were not considered. A second limitation is that an SLR is not exempt from subjectivity, despite the fact that participation and consensus among the authors can serve to keep it as low as possible. Despite these limitations, this review may be useful for any expert or individual interested in the topic of ‘football club finance and accounting’.

As for future lines of research, ‘FFP’ is well established, due both to the fact that contradictions have been detected in the literature and to the importance of this legislation for the management of clubs trying to participate in European competitions.

It would be very interesting to investigate how it has affected the competitive balance and possible implication in a new management model that seems to be originating in European soccer in search of financial efficiency, new forms of financing and its possible impact on the issue of a possible European super league. In terms of a second line of future research, there is the question of the valuation of ‘intangibles’. Because the latter are clubs’ largest asset item, the authors advocate a unification of the value at market price that would reflect a true and fair picture of clubs’ accounting statements. This could alter clubs’ financial potential and thus increase the spending limits dictated by FFP. Finally, mention should be made of the importance of researching the literature on the influence of foreign ownership, which has been on the rise in European soccer in recent years, and the negative effect on clubs that could be caused by too much concentration of ownership. (Acero et al., 2017; Rohde & Breuer, 2018; Sánchez et al., 2017).