The Role and Characteristics of National Accounting Standard Setters in the European Union: A Comparative Analysis

ABSTRACT

This paper examines the persistence of national/local institutions in accounting settings, where standards are global/international (or convergent). This poses the question of how these institutions adapt to a changing environment and what factors shape their structure. We provide updated information on 17 National Accounting Standard Setters (NASS) from 15 EU countries plus Australia and USA. The results reveal the four most relevant dimensions of each NASS (nature, organization, financing, and transparency) and identify two main models of NASS (public and private). The paper also discusses potential applications of this data, mainly to examine whether (and how) certain institutional factors could enhance the quality of financial reporting.

Keywords: National Standard Setters; Accounting regulation; Accounting standards; Institutional differences; Harmonization.

JEL classification: M40; M41; M48.

Función y características de los organismos nacionales de normalización contable en la Unión Europea: un análisis comparativo

RESUMEN

El trabajo estudia la persistencia de las instituciones nacionales/locales en un escenario (contabilidad) donde las normas son globales/internacionales (o convergen). Esto plantea la cuestión de cómo estas instituciones, que intervienen en un entorno cambiante, se configuran. Aportamos información actualizada sobre 17 Organismos Nacionales Reguladores de la Contabilidad (15 países de la UE más EE.UU. y Australia). Los resultados muestran las cuatro dimensiones más relevantes de cada organismo (naturaleza, organización, financiación, y trasparencia) y distinguen dos modelos de NASS (público y privado). El trabajo también sugiere diferentes vías para explotar y utilizar académicamente estos datos, principalmente para estudiar si (y cómo) las características de los NASS pueden mejorar la calidad de la información financiera.

Palabras clave: Reguladores nacionales de contabilidad; Regulación contable; Normas contables; Diferencias institucionales; Harmonización.

Códigos JEL: M40; M41; M48.

1. Introduction

In a global context of harmonization reached by European Directives during the last century, where the trend is to increase the comparability of financial reporting by applying a common accounting framework, European companies still live in a non-uniform world of accounting standards where each country defines its requirements through their National Accounting Standard Setter (NASS). Thus, despite the increasing globalization and convergence efforts of accounting standards, NASS still play an important role in shaping and influencing the accounting regulation and practice in their jurisdictions.

The persistence of NASS reflects that the countries are not willing to give up sovereignty. The fact that each EU country has its own NASS leads us to question how these bodies are formed, how they work, how they are financed, or whether they are transparent regarding their activities. Different NASSs remain in a global standard setting environment and it remains unclear how they differ and whether these differences are relevant.

Little is known about the characteristics, differences, and similarities of NASS across countries, as well as the factors that may affect their design and performance. This paper aims to fill this gap by providing a comprehensive and comparative analysis of the EU NASS, using a novel framework that captures multiple dimensions of their organization and functioning. It also explores the relationship between the NASS characteristics and the legal traditions of their countries, the IFRS adoption choices, as well as some indicators of Financial Reporting Quality (FRQ). This study also proposes new avenues to exploit the collected data.

Previous literature has explored various aspects of NASS, like Fédération des Experts Comptables Européens (2000), Benito & Brusca (2004), the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (2010), Sacer (2015), or Isidro et al. (2020). Our paper employs the methodological framework established by García et al. (2017), which analyses the attributes of public oversight systems for statutory auditors as outlined in Directive 2006/43/EC. Their framework categorizes relevant variables into distinct dimensions, facilitating a comprehensive examination of auditing bodies. We have seamlessly integrated this methodology into our analysis. However, our study diverges from García et al. (2017) in the exclusion of variables related to supervision and disciplinary mechanisms, as NASS do not fulfill a supervisory role.

This is a cross-country study that updates and extends the previous literature by investigating four dimensions of NASS: nature, organization, financing, and transparency. It focuses on 15 EU countries plus Australia and the USA. It provides a thorough analyses of the NASS in our sample.

This study contributes to the body of knowledge on accounting regulation by offering an in-depth analysis of the organizational and structural dimensions of NASS. It highlights the diverse nature of these entities, underscoring both the commonalities and disparities in their approach to the adoption of the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). A key discovery of this research is the persistence of NASS despite the ongoing efforts towards IFRS harmonization and convergence within the European Union and beyond, including countries like Australia and the United States of America. The continued existence of NASS in jurisdictions with a rich history of accounting regulation, as evidenced in our sample, points to the limitations of IFRS as a one-size-fits-all solution.

Another contribution of our paper is to provide a systematic compilation of data regarding the dimensions and variables of NASS characteristics. This dataset is a valuable resource for future research exploring the ramifications of NASS configurations in other areas like FRQ, as we illustrate in the paper.

Results are relevant to all national regulators who wish to rethink and reshape their NASS; in particular, the separation between accounting and auditing, and the allocation of regulation and supervision powers. It is also relevant to accounting researchers interested in labelling countries according to systemic variables (often used as control variables) such as general characteristics of NASS in different countries.

Section 2 explains the background and reviews the literature on NASS. Section 3 details the conceptual framework and the methodology. Section 4 presents the results by each dimension of NASS. Section 5 explains the potential utility of the collected data to other researchers. And finally, Section 6 concludes.

2. Background and literature review

Regulation 1606/2002 mandated that all European listed entities prepare their consolidated financial statements following the (endorsed) standards issued by the IASB. In 2009, the IASB also introduced IFRS for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), tailored for non-listed companies. These two developments could have been decisive for the transformation and demise of the NASS. However, this was not the case; NASSs still exist in nearly all European countries. Most of the EU countries retain the role of setting national standards for entities that do not apply either IFRS or IFRS for SMEs: unlisted companies, small/micro enterprises, not-for-profit, etc. Currently, only Ireland and the UK have adopted the IFRS for SMEs in Europe1.

EU countries had the option to either (1) regulate accounting standards for non-listed entities as well as parent (or separate) only financial statements of all companies, or (2) permit International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS2) to be applied generally. Most countries chose to keep their national sovereignty to maintain control over local or domestic accounting standards. The reasons for the persistence of NASS are still subject to further research. The positive theory of GAAP ‘… is premised on the idea that the objective of GAAP is to facilitate efficient capital allocation in the economy’ (Kothari et al., 2010). This efficient allocation has opened a vivid debate over the focus of accounting standards: performance measurement vs. stewardship. While we do not enter into the debate, we acknowledge that either way, GAAP is a way to exert control over businesses and the economy and, therefore, NASS becomes an important institution that influences financial reporting quality.

NASS have different characteristics, for instance, they may have a public or a private nature, have other functions (like auditing supervision), be financed through different sources, or show different levels of transparency in their activities. All these characteristics were often intertwined with legal and economic culture and tradition of each country, and overall, they shape different regulatory settings at country level that influence FRQ.

Since 2005, all NASS had to face several challenges. First, starting in 2005, countries could only regulate accounting for non-listed companies. These entities are generally medium or small and do not participate in complex activities and transactions that require highly technical accounting standards. However, given that listed entities must report their consolidated financial statements under IFRS, there was increased pressure to align domestic accounting with IFRS. Given the active agenda of the IASB in issuing high-quality global accounting standards, new and revised standards are issued at a much faster rate than most countries are used to. This rapidly changing regulatory environment requires countries to introduce changes to keep up with the IASB.

Zeff (2007) pointed out that global comparability (as a characteristic of FRQ) is highly influenced by the cultural factors of each country such as the financial and business culture, the accounting and auditing culture, or the regulation culture. The author specifically concluded that in those countries where the regulator is stronger, companies were less willing to deviate from IFRS because the regulator will oppose to changes in financial statements. Thus, the strength of the accounting regulator is important for worldwide comparability and certain factors can influence its strength, for example, the authority recognized by the Parliament or national law, its budget, competence, the quality of training of their employees, etc.

Although some studies have addressed the study of accounting standard setting from a historical perspective (Cortese & Walton, 2018), few studies have examined the configuration of NASS with an international comparability perspective3. The Fédération des Experts Comptables Européens (2000) collected characteristics of the NASSs before Regulation 1606/2002. This work classified each NASS by the nature (public/private bodies, the background of current members of the Boards of standard setters, the bodies with the right to nominate members of the Boards of standard setters), the funding, the relationships (the type of involved parties -accounting profession, preparers, stock exchange, academics, users, financial analysts, stock market regulator and other regulators, the tax administration and other governmental departments-), and the interpretation (the scope of the body4, and whether there is an urgent issues task force activity). The work described 20 European countries in 2000 (14 EU-countries5 -Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom-, 2 Non-EU countries -Norway, Switzerland-, 4 Central and Eastern European countries -Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania, Slovenia). The study suggested that the significant differences in structure and operation between standard setters in Europe may have hindered a European coordination of standard setters and explained why there was no such formal coordination at that time (FEE, 2000, p. 6).

On the other hand, the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA, 2010) studied the role of NASS in 9 jurisdictions, including some of the countries that had already adopted IFRS or were engaged in a transition to the use of IFRS (Australia, Canada, China, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Pakistan, Singapore, South Africa, UK and Ireland). All these countries continued developing national standards to some degree (for example, for public sector/not-for-profit entities, unlisted companies of SMEs, etc.). This work identified the following dimensions of the NASS for the above-mentioned countries: source of funding, resources-staff, resources-budget, and appointment of membership. ACCA recognizes advantages and disadvantages of the role of a NASS. Advantages include (ACCA, 2010, p. 4): (1) familiarity, (2) standard setting reflects national legal and economic tradition, and thereby excludes standards on matters that are irrelevant or are considered a rare application in the country; and (3) closer relationship to the tax system. Advantages of using global standards instead of national ones: (1) greater comparability of financial reporting within the country and with other countries, (2) higher quality of financial reporting than is apparent under national GAAP, (3) better understanding of financial information by users, (4) reduced complexity for preparers, users and auditors, and (5) easier education and training of accountants. The study concludes that in the long term, the use of national standards should decrease and this reduce the costs of maintaining a NASS. ACCA (p. 10) criticized the lack of information on the costs of NASS and considered probable that the costs of a NASS be significant when compared with the costs of IASB.

Finally, Sacer (2015) analyzed the national accounting standard-setting in 28 EU member states (27 EU member states6 + UK), the legal accounting framework, the application of GAAP, and the nature of accounting standard setting bodies. She found that 10 countries have a private professional NASS, 11 countries have a governmental (public) NASS, while the remaining 7 countries show a mixed public-private NASS model (p. 394). Sacer (2015) and FEE (2000) both studied whether the way accounting standards exist in an Accounting Act or in a Companies Act, or whether they have a set of accounting standards.

In our paper, we look at NASS as an institutional factor in the accounting environment. Our paper extends the results from FEE (2000), ACCA (2010), and Sacer (2015) by providing an updated detail of NASS characteristics and providing a database with all that information that may be used to study NASS as an institution with any other aspect of accounting (for instance, FRQ). Prior literature has analyzed the impact of different factors in the FRQ (Isidro et al., 2020). Other factors such as legal, culture, political, or economic factors, play a role in the way accounting regulation is shaped in each country. We contribute to previous literature on the characteristics of NASS and the persistence of these institutions despite the EU accounting harmonization efforts by providing an updated picture of the main characteristics of these local level institutions in a global standard setting environment, and investigates what differences exist among them, and whether those differences matter.

3. Conceptual framework and methodology

To study the current characteristics of NASS in the EU, the paper focuses on the core EU countries (those who joined the EU before 2000)7, and to provide the most up-to-date tables with detailed data of variables of these bodies. The paper adds Australia and USA to the sample of 15 EU countries as reference countries of high-quality financial reporting environments. Our sample include UK as EU country because we take the collected data before the BREXIT. Table 1 presents the list of the existing NASS across 15 EU countries plus Australia and USA.

Table 1. Competent authorities, national accounting standard-setter (NASS)

| Country | NASS | Website |

|---|---|---|

| Panel A: EU Countries | ||

| Austria | Austrian Financial Reporting and Auditing Committee (AFRAC) | www.afrac.at/ |

| Belgium | Commission des Normes Comptables (CNC) | www.cnc-cbn.be/fr |

| Denmark | Danish Business Authority (DBA) | www. danishbusinessauthority.dk/ |

| Finland | Kirjanpitolautakuna (KILA) | www.tem.fi/kirjanpitolautakunta |

| France | Autorité des Normes Comptables (ANC) | www.anc.gouv.fr |

| Germany | Deutsches Rechnungslegungs Standards Committee (DRSC) | www.drsc.de/ |

| Greece | Hellenic Accounting & Auditing Standards Oversight Board (ELTE) | www.elte.org.gr/index.php?lang=en |

| Ireland | - | - |

| Italy | Organismo Italiano de Contabilitá (OIC) | www.fondazioneoic.eu/ |

| Luxembourg | Commission des Normes Comptables (CNC) | www.cnc.lu |

| Netherlands | Raad voor de Jaarverslaggeving (RJ) | www.rjnet.nl/ |

| Portugal | Comissão de Normalizaçao Contabilistica (CNC) | www.cnc.min-financas.pt/ |

| Spain | Instituto de Contabilidad y Auditoría de Cuentas (ICAC) | www.icac.meh.es/ |

| Sweden | Bokföringsnämnden (BFN) | www.bfn.se/ |

| UK | Financial Reporting Council (FRC) | www.frc.org.uk/ |

| Panel B: Non-EU Countries | ||

| Australia | Australian Accounting Standards Board (AASB) | www.aasb.gov.au/ |

| USA | Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) | www.fasb.org/home |

Our methodological framework is based on García et al. (2017), which describes the auditing regulators and enforcement bodies in the European Union regarding the dimensions based on the Directive 2006/43/EC: basic characteristics, organizational structure, financing, transparency, supervisory mechanism, and disciplinary mechanism. García et al. (2017) is entirely descriptive and inspired our study to update and extend the research by previous literature on the setting of EU NASSs.

We do not use the dimension on enforcement as nearly none of the NASS have enforcement powers8 (only Denmark, -with certain limitations- Portugal, and the UK exert some powers in this area). Enforcement of accounting standards is left to other entities, mostly related with the regulation of capital markets, financial entities, and other regulated entities. The ESMA guidelines for the enforcement of accounting standards are followed by all European countries, and the ones applied by Australia and the USA do not -in substance- differ significantly from the ESMA model.

Thus, our conceptual framework contains descriptive evidence grouped in four dimensions: (1) basic characteristics, (2) organizational structure, (3) financing, and (4) transparency. Each dimension is further decomposed in several variables to capture the differences among the competent regulation bodies. Most of the variables used are taken from García et al. (2017). However, we dropped and added variables to the dimensions to adapt it to national accounting regulators. Table 2 offers the detail of the variables incorporated to each dimension.

Prior studies have shown that certain NASS characteristics have an impact on the accounting regulatory process. Rolleri (2016) designed a framework based on operations management literature to study how FASB modifications affected its performance. Voting rules, funding, and member’s background seem to affect the thoroughness, timeliness, and consensus of the FASB. Our paper focuses on observable variables rather than adopting a more behind the wall approach. However, our paper looks at several variables related to the ones identified by Rolleri (2016) like number of members, or using advisory and working groups, and highly qualified technical staff.

Table 2. Description of dimensions and variables of NASS

| Variable | Short Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Dimension 1: BASIC CHARACTERISTICS | ||

| Year of creation | YEAR | Year in which the body was officially established. |

| Nature | NATU | Takes the value 0 if NASS was created as public institution (e.g. included in a Ministry), and 1 if private. |

| Hierarchy | HIER | Hierarchical dependence. |

| Mision (1) | MISION | The NASS’s defined objectives and reported in their official webpage (Details in Appendix) |

| Dimension 2: ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE | ||

| Nº of members for the Board | MEMB | Number of members of the body that make decisions regarding accounting standards. |

| Appointment length | DURA | Duration of the term of members in years. |

| Advisory Groups (2) | ADVG | Whether the NASS uses Advisory Groups in the process of issuing accounting standards. Yes=1; No=0. |

| Working Groups (3) | WORG | Whether the NASS uses Working Groups in the process of issuing accounting standards. Yes=1; No=0. |

| High Qualified Technical Staff | HIQU | Whether the NASS hires High Qualified technical staff. Yes=1; No=0. |

| Dimension 3: FINANCING | ||

| Origin | FUND | Takes the value of 0 when the largest proportion of funding is provided from public sources, and 1 if private. |

| Sources | SOURCES | Sources of funding. |

| Fees as a Financing Source (4) | FEES | Whether the NASS collects fees other than memberships such as filing auditing reports fees of other services. Yes=1; No=0. |

| Amount | AMOUNT | Amount of financing. |

| Dimension 4: TRANSPARENCY | ||

| Annual Report | AVAR | Whether NASS prepares an Annual Report with its activities and makes it available through its web site. Yes=1; No=0. |

| English Annual Report | ENAR | Whether NASS provides an English version of its Annual Report. Yes=1; No=0. |

| Pages of Annual Report | PGAR | Number of pages of the last available Annual Report. |

| Due Process Availability | DPAV | It takes the value of 1 when the due process of issuing accounting standards is reported and available, either in the annual report or the web site, and 0 otherwise. |

Notes:

(1) The variable Mission refers to a description of the NASS’s objectives that is available on the official webpage, the variable does not report a numeric value. (2) Advisory Groups are part of the structure of the NASS and provides support to the decision-making body. (3) Working Groups are set for specific projects and goals. They are not part of the NASS structure but play an important role in the functioning. (4) We have considered membership fees as private because companies voluntarily decide to become members of an association and pay fees regularly. On the other hand, we consider administrative fees over deposited annual reports, auditing reports, and similar, as public funds because it represents compulsory fees that companies must pay. These fees are usually legally created and enforced. For example, Spain is considered ‘public’ in this dimension because most of its funding comes from fees charged to auditing entities for each auditing report it files with the auditing regulator.

4. Data and results

Table 3 Panel A summarizes the main characteristics of the NASS. Regarding the dimension 1 ‘Basic characteristics’, includes the following variables: Year of creation, Nature and Hierarchy dependence and Mission. All data was collected from the webpages and reported in the Appendix.

All 17 countries analyzed have a NASS except Ireland, which allows domestic entities to choose among IFRS, UK GAAP, or other similar GAAP (e.g., US GAAP). All other countries have some sort of domestic accounting standards for domestic entities. Some NASS were established around 50 years ago (e.g., FASB and KILA in 1973), but most of them have undergone recent changes, usually to assume more functions and responsibilities, especially after the EU regulation on IFRS in 2002. The only exception is the FASB in the USA, which has maintained its structure since its inception.

The NASS can be either public or private entities. Public NASS are integrated in a governmental body, such as a Ministry or Secretary of State, and issue opinions and/or recommendations that are later implemented into national legislation by amending current accounting laws or issuing new standards. This is the case of Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Greece, Luxembourg, Spain, and Sweden. Private NASS are independent bodies, usually with the legal form of a foundation or a professional organization, that receive their authority to issue mandatory accounting standards from a governmental agency (by a legal text). The due process for private NASS is generally more open to public comments and more transparent than for public NASS. Countries such as Germany, Italy, Netherlands, UK, and USA follow this system.

NASS also differ in their target audience of accounting standards. In Belgium, France, Italy, Portugal, the UK, and the USA, the NASS issue standards at national level for all domestic entities. In Germany, the accounting standards issued by its NASS apply only to consolidated accounts of non-listed entities. In Spain, national accounting standards are targeted for small and medium-sized enterprises and unlisted enterprises. In Sweden, only unlisted companies must comply with national accounting standards.

Table 3 Panel A also shows the organizational structure of the NASS for dimension 2 ‘Organizational structure’. We focus on the specific structures within NASS that deal with accounting regulation. The NASS have different governing structures, sizes, compositions, terms, and profiles of their members.

The size of the bodies varies from 5 (as in Greece or in Spain) to 20 (as in Austria or Germany), with an average of 13 members. There seems to be a preference for private NASS to have larger bodies. Austria and Germany have the largest number of members and are private. Italy is also private and has 16 members although it could have as much as 19. The Netherlands Board has 10 members. The exception to this rule is the US FASB, comprised of only 7 members.

The composition of the governing bodies reflects the diversity of stakeholders involved in accounting regulation. Countries with many members (more than 10) include representatives of investors, supervisory bodies, insurance companies, financial institutions, listed companies from different sectors, academics, auditors, financial analysts, ministries and civil servants. For example, in France, the board also includes three judges and a trade union representative. A possible explanation is that private NASS are supported by a larger number of stakeholders that demand a seat in the decision-making body. On the other hand, public NASS often represent governmental interests. For example, in Spain, the Consejo de Información Corporativa (Corporate Information Board)9, has only four members: the President (chosen by the government), and one representative from each of other accounting standard setting bodies of industry specific sectors: the Bank of Spain (for financial institutions), the Directorate General for Pension and Mutual Funds (for insurance and investment entities), and the National Securities Exchange Commission (for listed entities). A fifth member from the ICAC, playing as secretary of the Board, attends meetings with no voting rights. However, Portugal has a public NASS with a large number of members (19) that reflects the interests of several industries and institutions, like in Germany.

The term of appointment for the members is on average 3.7 years. It varies from 3 years (in Australia, Austria, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Sweden, and the UK) to 6 years (in Belgium). In the USA, the term is 5 years (renewable for up to 10 years). In Spain, the term depends on the background and training of the representatives from different bodies. Most of the members work full-time, except for Australia, where they work part-time (except for the President). In Australia, gender considerations are also considered in the board composition.

The profile of the members varies significantly and may have an impact on standard setting (Allen & Ramanna, 2013; Witzky, 2017). All of them are assisted by a staff with extensive experience and training in accounting, auditing, and related areas, with academic and/or professional backgrounds. In addition, NASS may have Advisory Groups (France, Germany, Spain, United Kingdom), or Working Groups (Germany, Luxembourg, Spain, USA) with highly qualified staff who provide technical support (Germany, Greece, Italy, Netherlands, Sweden, USA). Technical staff are required to have extensive professional experience in accounting and financial information. Working Groups are mostly composed of auditors, academics, and financial reporting managers. In the case of Australia, gender considerations are considered in the composition of the Board. Both, private and public NASS seem to have Advisory Groups, technical support staff, or Working Groups.

Table 3 Panel B shows the financing of the NASS for dimension 3. We classify NASS financing according to the primary source of funds: public sector (governmental agency) or private sector. A NASS is ‘public’ or publicly funded when most or all of the budget comes from public sources. A NASS is ‘private’ or privately funded when most or all of the budget comes from private sources. In some cases, NASS receive funds from both sources. For example, Australia’s budget was AUS $5.1 million in 2019, out of which AUS $3.6 million were provided by the Government and AUS $1.5 million were generated by their own-source income (sale of goods, management fees, contributions from State and Territories, etc.). Since most of the funding comes from public sources, we classify Australia as public in terms of financing. The German DRSC received €2.4 million in 2018 from membership fees, licenses, publications, and other similar sources, which qualifies as ‘private’ in the financing dimension.

There seems to a perfect correlation between the public vs private nature of NASS described in dimension 1 and the source of funding as described in this section. Public NASS are funded through public means, and private NASS are funded through private means. All 11 public NASS (Australia, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Greece, Luxembourg, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the UK) receive most of the funding from public sources. The UK presents a mixed model whereas Government and companies contribute to the financial support. Austria, Germany, Netherlands, and the USA are financed through private funds. Finally, the exception to the rule is Italy, whereas despite being a private NASS, is funded through public sources. Italy’s budget was €3,17 million in 2019, when €2,7 million came from mandatory charges to the companies (considered public source), and €350.000 from founders (considered private source).

All privately funded NASS (Austria, Germany, Netherlands, and the USA) collect membership fees and receive funds from selling and distributing publications or delivering services (such as professional reports). Only 4 of the 11 publicly funded NASS (Belgium, Greece, Italy, and Spain) collect fees from companies. In most cases fees come from the deposit of annual accounts on Accounting and Company Registries while in others it comes from the deposit of auditing reports from auditing firms. For example, in Spain, the ICAC is self-financed through two types of sources: a) control and supervision fees on auditing and, b) fees charged for certificates and inscriptions on the Register of Auditors. The ICAC is simultaneously the NASS and the Auditing Regulatory and Supervisory Body. We classified the ICAC as ‘public’ for funding purposes as the fees are legally required, even though fees come from auditing and not accounting functions.

The NASS can be ranked by the volume of revenues (in millions €): Luxembourg (0.3), Netherlands (0.86), Sweden (1.1), Belgium (1.5), Germany (2.4), Greece (2.4), Italy (3.17), Australia (5.1), Spain (8.5), UK (30.5), and USA (41). These figures should be taken with caution as in some cases, as described above, the NASS assume also other functions. The UK FRC is one of the few that undertakes the monitoring and enforcing of accounting standards, a function requiring important amounts of resources. We found no information was found regarding the budget of Austria, Denmark, Finland, France, and Portugal.

The dimension 4 ‘Transparency’ (Table 3 Panel A) refers to the level of disclosure of information of each NASS regarding (1) their activities and (2) their due process. We looked in their web sites for an annual report or similar documents, information on the agenda topics, discussion papers, standards, recommendations, and related information.

Most of the countries (Australia, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Greece, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, UK, and USA) disclose an annual report with information about their activities. France has not published an annual report since 2016. Further references to France refer to the last available annual report. We could not find the annual report of Austria, Finland, and Italy.

Out of the 11 NASS with an annual report available, only 5 disclosed an English version: Australia, Germany, Spain, UK, and USA. Having an English version of the annual report increases transparency and accountability of the NASS, as well as it gives it an international projection of their activities.

When considering their public or private nature, all 9 public NASS except Finland and France reported an annual report. Among the 5 private NASS, only Germany, Netherlands, and the USA, have an annual report available. Austria reports their financial statements but not a full report or information regarding their activities. Austria and Italy seem to submit their annual report directly to the Government rather than making it available on their website. In terms of length, the average number of pages of the annual report is 50 (for the last available annual report). Australia (122 pages), UK (96), and Spain (98) have the longest annual reports, and Luxembourg (5 pages), Portugal (14), and Belgium (17), the shortest.

There is a significant heterogeneity in the content of annual reports. While some countries disclose information about their meetings, activities, financial statements, auditing report, annual budget, and collaboration with international bodies, others hardly offer a brief reference to some activities. For example, the annual report from the Netherlands includes meetings, topics for discussion, the issued and adopted standards, the annual budget, the balance sheet, and the auditor’s report. France, in their last available annual report in 2016, reported only a brief description of the activities as a standard setter but did not include quantitative information or financial statements.

The due process and current accounting standards are also important aspects of the role of NASS as regulators, but the level of disclosure of these activities is not always the same. Regarding the availability of local accounting standards and regulation changes, all countries have their current accounting regulation and standards available on their website. It is important to mention that domestic GAAP take different shapes. For instance, in the UK there are accounting standards issued by the FRC, each of them addresses one particular issue and the standards are disclosed separately. In other countries like for instance, Denmark, Finland, or Spain, GAAP are comprised in a legal item (law, decree, order). In the former case, individual standards are disclosed on the website while in the latter, a link to the legal document provides access to the accounting legislation.

The available information regarding due process is also very different, varying from a very complete and open access to all stages of the due process (agenda, discussion papers, technical committee meetings, drafts of the standards), to an absolute absence of information. Australia, Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Sweden, United Kingdom, and USA make their due process open to the public in their website. In Germany, for example, the standard-setting process is subject to public scrutiny and discussion at different levels according to the relevance of the topic. In fact, stakeholders can participate in the process through different means. On the other side of the spectrum, France does not provide any access to the standard-setting process, and accounting standards are only available when the process has ended. It is interesting to notice that all private NASS are transparent regarding their due process, while only 5 of the 11 public NASS do the same. In most cases, public NASS issue recommendations and opinions on current accounting legislation, and only in limited cases need further legal recognition. Thus, the technical and political debate is limited to governmental and other regulatory stakeholders. Private NASS, however, seem to be more transparent to the variety of stakeholders and financial supporters they depend.

Table 3. Dimensions and variables

| Panel A: Dimensions 1, 2 & 4 -Basic characteristics, Organizational structure & Transparency | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension 1 | Dimension 2 | Dimension 4 | ||||||||||||||

| Country | NASS | Year | NATU | HIERARCHY | MEMB | DURA | ADVG | WORG | HIQU | AVAR | ENAR | PGAR | DPAV | |||

| Australia | AASB | 1991 | 0 | Ministry of Pensions & Corporate Law | 13 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 122 | 1 | |||

| Austria | AFRAC | N/A | 1 | Independent | 20 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | N/A | 1 | |||

| Belgium | CNC | 1975 | 0 | Ministry of Finance | 17 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 17 | 1 | |||

| Denmark | DBA | 2012 | 0(1) | Ministry of Business | 15 | N/A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 55 | 0 | |||

| Finland | KILA | 1973 | 0 | Ministry of Economy and Employment | 8/12 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | N/A | 0 | |||

| France | ANC | 2009 | 0 | Ministry of Economy and Finance | 16 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 (2) | N/A | N/A | 1 | |||

| Germany | DRSC | 1998 | 1 | Independent | 20 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 57 | 1 | |||

| Greece | ELTE | 2003 | 0 | Ministry of Economy and Finance | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 30 | 0 | |||

| Ireland | - | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Italy | OIC | 2014 | 1 | Independent | 16 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 (3) | N/A | N/A | 1 | |||

| Luxembourg | CNC | 2002 | 0 | Government of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg | 12 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 0 | |||

| Netherlands | RJ | 1981 | 1 | Independent | 10 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 38 | 1 | |||

| Portugal | CNC | 2012 | 0 | Ministry of Finance | 19 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 16 | 0 | |||

| Spain | ICAC | 1990 | 0 | Ministry of Economy, Industry & Competitiveness | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 88 | 0 | |||

| Sweden | BFN | 1976 | 0 | Ministry of Finance | 11 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 27 | 1 | |||

| UK | FRC | 2012 | 0 | Secretary of State for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy | 10 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 96 | 1 | |||

| USA | FASB | 1973 | 1 | Independent | 7 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 48 | 1 | |||

Notes: (1) In 2012 the body turned into public; thus, this information differs from data collected by previous works as FEE (2000) or Sacer (2015). (2) Last annual report available is from 2016. (3) Italy prepares and submit an annual report directly to the Government but does not make it available in their website.

| Country | NASS | FUND | SOURCES | FEES | AMOUNT (1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | AASB | 0 | Australian Government | 0 | 5,1 $ (2019) (2) |

| Austria | AFRAC | 1 | Membership fees, donations, subventions, and sponsorships, as well as income from developing expert opinions and publications | 0 | N/A |

| Belgium | CNC | 0 | Fees over the published annual reports of the companies, associations, and foundations | 1 | 1,5 € (2018) |

| Denmark | DBA | 0 | General budget of Danish Government (3) | 0 | N/A |

| Finland | KILA | 0 | General budget of Finish Government (4) | 0 | N/A |

| France | ANC | 0 | General budget of the French Government. It is possible to obtain financing from the private sector too | 0 | N/A |

| Germany | DRSC | 1 | Membership fees, licenses, publications, and other income | 0 | 2,4 € (2018) |

| Greece | ELTE | 0 | Contributions paid by the regulated entities. Its operations expenses do not burden the state budget (5) | 1 | 2,4 € (2015) |

| Ireland | - | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Italy | OIC | 0 | Administrative surcharges and secretary fees on the accounting deposit (6) | 1 | 3,17 € (2019) |

| Luxembourg | CNC | 0 | State subsidy mainly (and fees from memberships) | 0 | 0,297 € (2018) |

| Netherlands | RJ | 1 | Revenues from the Social and Economic Council, NBA (the Royal Netherlands Institute Chartered Accountants), and Eumedion (Corporate Governance Forum) contribute to the Foundation's budget. The Foundation also receives revenues from copyrights of the DAS | 0 | 0,860 € (2018) |

| Portugal | CNC | 0 | General budget of Portuguese Government | 0 | N/A |

| Spain | ICAC | 0 | General budget of Spanish government, fees on published annual reports and auditing reports, public administrative surcharges, and others (7) | 1 | 8,6 € (2018) |

| Sweden | BFN | 0 | General budget of Sweden Government | 0 | 1,1 € (11,7 SEK) |

| UK | FRC | 1 | Mainly funded by the audit profession (accountancy, actuarial professions, preparers, insurance companies and pension schemes. Other income from publications and electronic rights, and other | 1 | 39,5 £ (2019/20) |

| USA | FASB | 1 | Support fees, publishing, etc. | 1 | 45,5 $ (2018) |

Notes: (1) In million. (2) 3,6 million € from the Government + 1,5 million € from others Own-Source Income (fees, contributions from State and Territories, etc.)

(3) The body became public in 2012, until then was financed by membership fees (FEE, 2000). (4) Despite there is no organism, the Ministry of Economy and Employment is the responsible of issuing accounting standards. It is supported by an accounting board (Kirjanpitolautakunta - KILA) that issues recommendations and exemptions in accounting matters. (5) This body is simultaneously the authority of the audit profession, the quality of audits and accounting and auditing standards and practices. (6) 350.000€ from founders and 2,7 million € from charges to the companies. (7) ICAC is at the same time the NASS and the Auditory Supervision Body. The body is self-financed through two types of sources: a) control and supervision fees on the auditory; and b) fees charged for certificates and inscriptions on the Register of Auditors.

Table 4 presents the descriptive statistics of the numerical variables in our paper. We exclude some variables that are narrative or do not provide meaningful numerical values. The results show that most NASS are public (mean = 0.294), reflecting the governmental control over financial reporting. This is consistent with Sacer (2015), who found that almost half of EU countries (28) had governmental organizations as NASS. The decision-making board has an average of 12.1 members and an average term of 3.2 years. About 25% of the NASS have Advisory Groups or Working Groups (mean = 0.235), and only one third of them have high technical staff (mean = 0.353). The NASS are mostly funded by public sources (mean = 0.294) and only a minority charge fees as a revenue source (mean = 0.353). Most of them publish an annual report (mean = 0.706) with an average length of 35 pages, but only a few have it in English (mean = 0.294). The due process is reported by almost two-thirds of the NASS (mean = 0.588).

Table 4. Variable values, descriptive and data statistics

| Dim 1 | Dim 2 | Dim 3 | Dim 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NASSS | NATU | MEMB | DURA | ADVG | WORG | HIQU | FUND | FEES | AVAR | ENAR | PGAR | DPAV |

| AUS | 0 | 13 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 122 | 1 |

| AUT | 1 | 20 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 1 |

| BEL | 0 | 17 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 17 | 1 |

| DNK | 0 | 15 | N/A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 55 | 0 |

| FIN | 0 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | N/A | 0 |

| FRA | 0 | 16 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 1 |

| GER | 1 | 20 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 57 | 1 |

| GRC | 0 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 30 | 0 |

| IRL | - | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| ITA | 1 | 16 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 1 |

| LUX | 0 | 12 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| NLD | 1 | 10 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 38 | 1 |

| PRT | 0 | 19 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 16 | 0 |

| SPA | 0 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 88 | 0 |

| SWE | 0 | 11 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 27 | 1 |

| UK | 0 | 10 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 96 | 1 |

| USA | 1 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 48 | 1 |

| N | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 |

| Mean | ,294 | 12,118 | 3,235 | ,235 | ,235 | ,353 | ,294 | ,353 | ,706 | ,294 | 35,235 | ,588 |

| Median | 0 | 12 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 27 | 1 |

| St.Des | ,470 | 5,721 | 1,522 | ,437 | ,437 | ,493 | ,470 | ,493 | ,470 | ,470 | 37,881 | ,507 |

| Min | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Max | 1 | 20 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 122 | 2,09 |

In the following section we show how this database of NASSs’ characteristics may be used in other works.

5. The usefulness of NASS’s characteristics data for research

Table 4 presents the characteristics of the NASS across 17 countries. This data can be used by researchers to examine the institutional influences on accounting and financial reporting practices in different contexts.

5.1. NASS stereotypes

A first approach to use the data is to identify if there are patterns or stereotypes in how NASS are designed. In other words, is there a ‘best’, ‘optimal’, or ‘unique’ NASS model, defined by its characteristics? Do NASS characteristics tend to group and form ‘stereotypes?

Table 5. Spearman Correlation among NASS variables for countries in our sample

| [1] | [2] | [3] | [4] | [5] | [6] | [7] | [8] | [9] | [10] | [11] | [12] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] NATU (Pri=1, Pub=0) | 1 | |||||||||||

| [2] MEMB (number) | ,235 | 1 | ||||||||||

| [3] DURA (years) | ,065 | -,196 | 1 | |||||||||

| [4] ADVG (Yes=1, No=0) | -,078 | -,016 | -,052 | 1 | ||||||||

| [5] WORG (Yes=1, No=0) | ,234 | -,189 | ,451 | ,333 | 1 | |||||||

| [6] HIQU (Yes=1, No=0) | ,592* | -,211 | -,015 | -,149 | ,149 | 1 | ||||||

| [7] FUND (Pri=1; Pub=0) | ,709** | ,044 | ,065 | ,234 | ,234 | ,313 | 1 | |||||

| [8] FEES (Yes=1; No=0) | ,035 | -,436 | ,372 | ,149 | ,149 | ,200 | ,035 | 1 | ||||

| [9] AVAR (Yes=1; No=0) | -,234 | -,299 | ,347 | ,000 | ,333 | ,149 | ,078 | ,149 | 1 | |||

| [10] ENAR (Yes=1; No=0) | ,127 | -,250 | ,146 | ,545* | ,545* | ,035 | ,418 | ,313 | ,389 | 1 | ||

| [11] PGAR | ,139 | -,196 | ,355 | ,585* | ,051 | -,073 | ,358 | ,171 | - | ,808** | 1 | |

| [12] DPAV (Yes=1; No=0) | ,522* | ,310 | -,015 | ,149 | -,149 | ,333 | ,522* | ,067 | -,149 | ,244 | ,318 | 1 |

Table 5 shows Spearman correlations between NASS variables. Overall, there are few significant correlations among them. NATU correlates positively and significantly with HIQU (,592*)10, FUND (,709**), and DPAV (,522*). This result suggests that a private (public) NASS is more (less) likely to hire high qualified staff, have most of its funding through private (public) sources, and to disclose (not disclose) its due process. A NASS that discloses an English annual report (ENAR) seems more likely to use Advisory Groups (ADVG; ,545*), Working Groups (WORG; ,545*), and have a larger annual report (PGAR; ,808**). Similarly, NASS that use Advisory Groups (ADVG) are likely to disclose longer annual reports (PGAR; ,585*). Finally, a NASS that is funded mostly through private sources (FUND) has a higher propensity to disclose its due process (DPAV; ,522*).

5.2. NASS and legal family’s persistence

Prior literature has identified how countries gather in clusters due to their similarities in several aspects like investor protection, enforcement of law, economic development, or culture. La Porta et al. (1998) used the concept of legal families where they classified countries according to several country variables. Implicitly, institutions in each legal family shared some common characteristics. La Porta et al. (1997, 1998) explored the relationship between law and financing (equity versus debt), ownership concentration, and enforcement of rules in different legal families or traditions based on European legal traditions: common law and the three civil law families (French, German, and Scandinavian). Leuz et al. (2003) and Leuz (2010) found that those legal families remain relevant to explain other aspects of financial reporting.

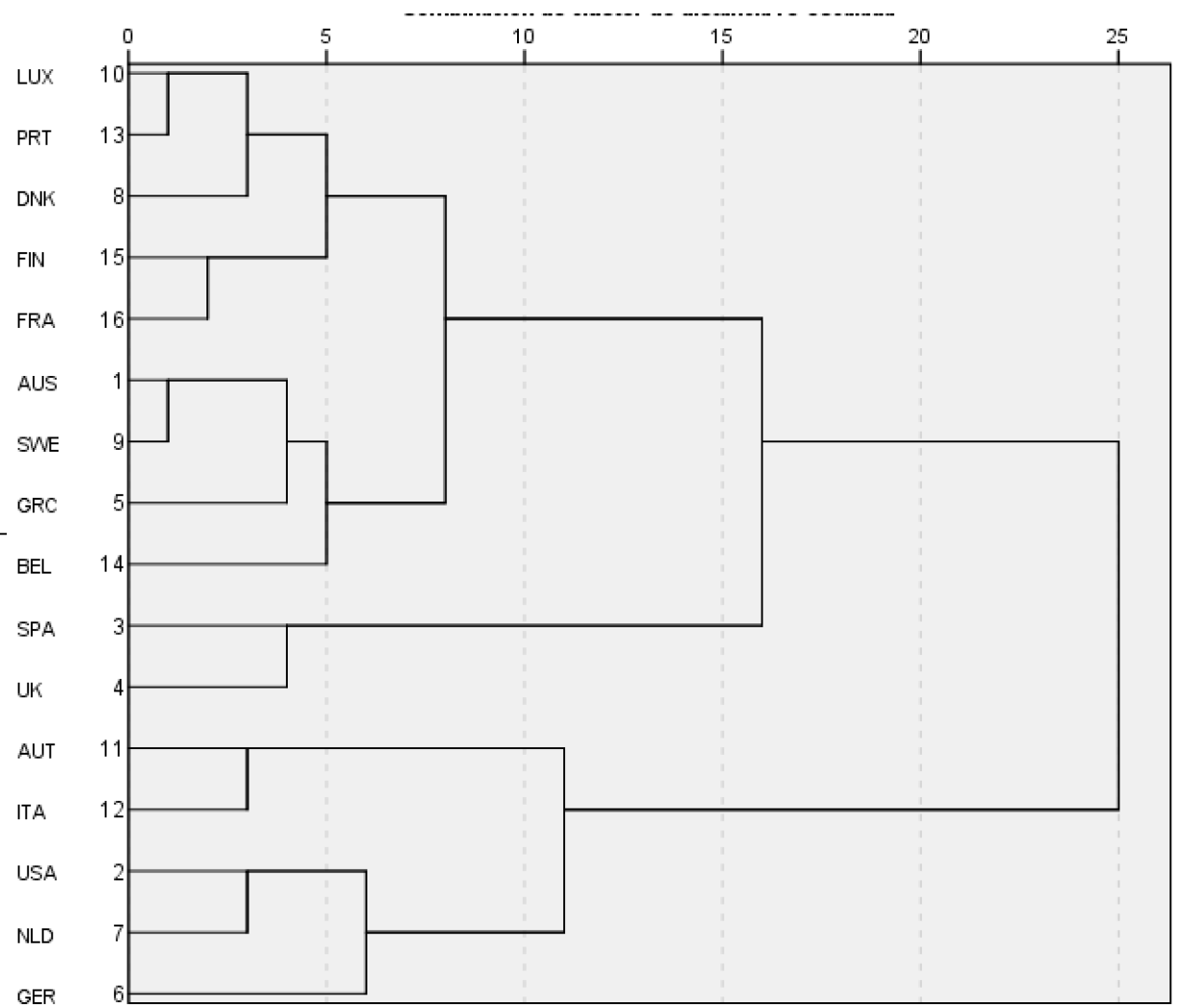

Since NASS are institutions in the accounting regulation arena, we expect that NASS design may be influenced by such legal families11. This section explores whether those legal families persist in NASS design, or whether recent changes in accounting regulation (like the adoption of IFRS) has somehow eroded the distinction of legal families. To explore this possibility, we used hierarchical cluster analyses to group countries according to their NASS characteristics12. Figure 1 shows the dendrogram with the clustering of countries in our sample according to the NASS characteristics13. At a distance of 15, three clusters emerge:

Cluster 1: LUX, PRT, DNK, FRA, FIN, AUS, SWE, GRC, BEL

Cluster 2: SPA, UK

Cluster 3: AUT, ITA, NLD, USA, GER

Our results suggest that NASS design does not seem to align much with legal families. Cluster 1 includes most of countries traditionally classified as ‘Civil Law’ except AUS. DNK, FIN, and SWE are Scandinavian subtype under Civil Law legal family. Common law countries (UK, USA, and AUS) are classified in different clusters, along with other civil law countries. Cluster 3 includes one common law country (USA) and four civil law countries. In a 2-cluster model, countries in cluster 2 merge into cluster 1, what would make cluster 1 have 2 common law countries and 9 civil law countries, and cluster 2 with 1 common law country and 4 civil law.

Figure 1. Dendrogram from cluster analyses of countries according to their NASS characteristics

It is interesting to notice that civil law countries with a private NASS, such as GER, AUT, and ITA, are classified along with common law countries, signalling that legal traditions may be influencing the way NASS are designed. As correlations suggest, having a private NASS goes along with a more qualified and complex working team (highly qualified staff, working and advisory groups), and having higher levels of transparency (disclosure). Civil law countries that adopted these measures in their NASS design, were classified along with common law countries. Future research might shed light on why these countries decided to design their NASS with a private nature instead of following the tradition.

5.3. NASS characteristics and Financial Reporting Quality

Country factors (such as social, cultural, political, and economic aspects) influence all institutions within a country, including the National Accounting Standards Setters (NASS). NASS may be considered as accounting institutions that shape the accounting and financial reporting practices in each country. Many studies have examined the attributes and characteristics of accounting and financial reporting, such as Financial Reporting Quality (FRQ). FRQ is a widely used accounting feature that can be defined and measured in various ways. However, it is generally accepted that FRQ depends on several country and institutional factors (Leuz, 2010; Isidro et al., 2020). Therefore, NASS can also be seen as a factor that affects FRQ in different countries.

Our data set can be used to study whether NASS characteristics play any role in the FRQ levels. As an example, we follow Isidro et al. (2020) to measure FRQ with six different measures taken from the literature: Reporting Transparency (REPTRANS), Disclosure Quality (DISCLQUAL), Abnormal Return (ABNRET), Abnormal Volume (ABNVOL), Return Synchronicity (RETSYNC), and Asymmetric Timeliness (ASYMTIME)14. Table 6 below shows the descriptive statistics of these variables for all countries in our sample.

Table 6. Descriptive statistics of FRQ variables (Isidro et al., 2020)

| N | Mean | Median | Sth.Dv | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reporting Transparency | 16 | -,51 | -,53 | ,29 | -,88 | -,08 |

| Disclosure quality | 16 | 72,94 | 74,50 | 8,80 | 56,00 | 85,00 |

| Asymmetric timeliness | 16 | ,22 | ,23 | ,15 | -,09 | ,50 |

| Abnormal return | 16 | 5,52 | 5,17 | 1,85 | 3,49 | 9,34 |

| Abnormal volumen | 16 | ,97 | ,957 | ,59 | -,01 | 1,91 |

| Return synchronicity | 16 | 1,74 | 1,80 | ,29 | 1,02 | 2,14 |

Spearman correlations between NASS and these FRQ variables are presented in Table 7. Only ASYMTIME is significantly correlated with three NASS variables: AVAR, ENAR, and PGAR, (all transparency measures). The correlation is positive meaning that in countries whose NASS is more transparent, accounting information is more related to market information (prices and returns). This is not a surprising result as most of the FRQ measures are related with transparency, disclosure, and capital market information. Alternative measures of FRQ like using accruals may show different results on the relationship between NASS characteristics and FRQ.

Table 7. Spearman correlations between NASS variables and FRQ values for each country

| [13] REPORTTRANS | [14] DISCLQUAL | [15] ASYMTIME | [16] ABNRET | [17] ABNVOL | [18] RETSYNC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] NATU (Pri=1, Pub=0) | -,131 | -,328 | -,262 | 0 | ,033 | ,131 |

| [2] MEMB (number) | -,27 | -,374 | -,284 | -,28 | -,35 | ,187 |

| [3] DURA (years) | -,151 | -,218 | ,216 | -,057 | -,028 | -,024 |

| [4] ADVG (Yes=1, No=0) | ,07 | ,21 | ,07 | ,07 | 0 | ,209 |

| [5] WORG (Yes=1, No=0) | 0 | -,077 | ,347 | -,116 | -,039 | ,193 |

| [6] HIQU (Yes=1, No=0) | -,063 | -,173 | ,031 | -,126 | ,157 | -,126 |

| [7] FUND (Pri=1; Pub=0) | ,229 | ,033 | -,065 | ,36 | ,229 | ,393 |

| [8] FEES (Yes=1; No=0) | -,22 | -,126 | ,094 | -,094 | ,094 | -,283 |

| [9] AVAR (Yes=1; No=0) | ,209 | ,017 | ,698** | ,105 | ,105 | ,174 |

| [10] ENAR (Yes=1; No=0) | ,426 | ,295 | ,589* | ,196 | ,131 | ,458 |

| [11] PGAR | ,465 | ,297 | ,696** | ,305 | ,182 | ,362 |

| [12] DPAV (Yes=1; No=0) | ,393 | ,246 | ,033 | ,393 | ,327 | ,426 |

Note: Data for Luxembourg is not used in Isidro et al. (2020), so this table does not include it either.

5.4. NASS characteristics and IFRS adoption patterns

The level of convergence or comparability between domestic GAAP and IFRS is relevant to the study of EU accounting harmonization. It may be argued that EU countries have adopted their accounting regulation to align with IFRS. Hope et al. (2006) argue that countries ‘(…) view that IFRS represent a vehicle through which countries can improve investor protection and make their capital markets more accessible to foreign investors’. Therefore, NASS may be more inclined to adopt IFRS. There is an extensive literature analysing the causes and effects of adopting IFRS.

Our paper focuses not on any of these but on the actual decision of each NASS to allow or prohibit IFRS in their jurisdiction. We study whether the specific configuration of each NASS is related to the level of acceptance of NASS. To measure this, we used dummy variables to identify whether a country prohibits (value = 0) or allows or requires (value = 1) IFRS in the following situations: LISE = LIsted companies, SEparate financial statements; LICO = LIsted companies, COnsolidated financial statements; UNSE = UNlisted companies, SEparate; UNCO = UNlisted, COnsolidated; PISE = PIE15, SEparate; and PICO = PIE, COnsolidated. Thus, when LISE takes the value of 1, that country allows or requires the use of IFRS to prepare the separate financial statements of listed companies. However, if IFRS are not allowed and listed companies must apply domestic GAAP to prepare their separate financial statements, LISE would have a value of 0. Considering the EU setting, LICO always takes a value of 1 as consolidated statements of listed companies must use IFRS (as adopted by the EU) since 2005. Finally, we computed IFRSi as the sum of all IFRS variables and works as an index of the tolerance of each country regarding the use of IFRS for financial reporting of domestic companies. Countries with high values of IFRSi are more tolerant with (accept more widely) the use of IFRS (or are required). Table 8 shows the values of these variables for each country.

Table 8. Options each country made regarding the adoption of IFRS for domestic companies

| Country | LISE | LICO | UNSE | UNCO | PISE | PICO | IFRSi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUT | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| BEL | 016 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| DNK | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| FIN | 117 | 1 | 118 | 117 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| FRA | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| GER | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| GRC | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| IRL | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| ITA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| LUX | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| NLD | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| PRT | 1 | 1 | 119 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| SPA | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| SWE | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| UK | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| AUS(1) | 120 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| USA(1) | 0 | 0 | 021 | 020 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mean(full sample) | ,588 | ,941 | ,588 | ,941 | ,412 | ,647 | 4,118 |

| St.Dev.(full sample) | ,507 | ,243 | ,507 | ,243 | ,507 | ,493 | 1,867 |

| Mean(EU only) | ,600 | 1 | ,600 | 1 | ,400 | ,667 | 4,267 |

| St.Dev.(EU only) | ,507 | 0 | ,507 | 0 | ,507 | ,488 | 1,580 |

Notes: (1) Non-EU countries.

0 if prohibited; 1 if allowed or required. IFRSi is an index that adds all variables.

The mean values of LICO and UNCO are very close to 1 (0.941 for both), meaning that a substantially majority of countries accept or require IFRS for consolidated financial statements (only exception is the USA). However, there exists some heterogeneity for the level of acceptance of IFRS for separate financial statements (mean value is 0.588). This means that NASS keep their sovereignty to regulate accounting standards for separate statements of domestic companies, which in many countries account for the largest proportion of companies.

We can group countries in three clusters according to IFRSi:

Cluster 1: ITA, IRL, GRC, NLD, UK, AUS, FIN, PRT (high tolerance of IFRS, IFRSi >= 5)

Cluster 2: BEL, DNK, LUX, AUT, SWE (medium tolerance for IFRS)

Cluster 3: FRA, DEU, SPA, USA (low tolerance of IFRS, IFRSi <= 2)

Cluster 1 includes countries with a high level of tolerance or acceptance of IFRS for domestic reporting, IFRSi is equal to or larger than 5 (6 is maximum value). Cluster 2 has a medium level of tolerance (IFRSi between 4 and 3), and cluster 3 holds countries with a low level of tolerance of IFRS (values 2 or less). Cluster 1 is the largest with 8 countries showing a high level of tolerance of IFRS. This is not a surprise as all are EU countries (except AUS), highly exposed to IFRS usage. On the other hand, countries like FRA, SPA, and GER show the lowest level of IFRS tolerance.

Common law countries (USA, IRL, UK, AUS) show different levels of tolerance, from 0 (USA) to 6 (AUS, IRL, UK). Civil law countries seem more aligned at the highest end of tolerance except for FRA, SPA, and GER. Their NASS were classified in three different clusters, so their design does not seem to be responsible for their accounting policy choices regarding the acceptance of IFRS. For instance, FRA and SPA have public NASS while GER is private. The distinction between common law and civil law countries does not hold for the choice of IFRS acceptance. Further research is needed to explore this behavior.

When computing Spearmen bivariate correlation of NASS characteristics and IFRS choices (see Table 9) only shows a negative and significant correlation between using working groups and IFRS for consolidated statements of PIEs (-,75**). Using advisory groups, working groups, and disclosing an English annual report has a negative and significant correlation with IFRSi (-,524*, -,604*, and -,816** respectively). Although this is difficult to interpret, this result suggests that NASS with a more complex due process (more participation) and disclosing an English annual report (and hence, more transparency), is more likely to produce a lower tolerance of IFRS in general. This is the case of GER and SPA (ADV=1, WORG=1, ENAR=1), but not FRA (ADV=1, WORG=, ENAR=0).

Table 9. Spearman correlations between NASS variables and IFRS options

| LISE | LICO | UNSE | UNCO | PISE | PICO | IFRSi | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] NATU (Pri=1, Pub=0) | -,221 | -,383 | -,221 | -,383 | ,035 | -,035 | ,045 |

| [2] MEMB (number) | -,206 | ,310 | -,206 | ,310 | -,169 | ,042 | ,135 |

| [3] DURA (years) | -,287 | -,372 | -,287 | -,372 | ,031 | -,093 | -,176 |

| [4] ADVG (Yes=1, No=0) | -,364 | ,149 | -,364 | ,149 | -,149 | -,447 | -,524* |

| [5] WORG (Yes=1, No=0) | -,364 | -,447 | -,364 | -,447 | -,447 | -,745** | -,604* |

| [6] HIQU (Yes=1, No=0) | -,098 | -,333 | -,098 | -,333 | ,200 | ,067 | ,156 |

| [7] FUND (Pri=1; Pub=0) | -,221 | -,383 | -,221 | -,383 | ,035 | -,035 | -,312 |

| [8] FEES (Yes=1; No=0) | -,098 | -,333 | -,098 | -,333 | ,467 | ,067 | ,014 |

| [9] AVAR (Yes=1; No=0) | ,073 | -,149 | ,073 | -,149 | ,149 | -,149 | -,270 |

| [10] ENAR (Yes=1; No=0) | -,221 | -,383 | -,221 | -,383 | ,035 | -,313 | -,816** |

| [11] PGAR | -,024 | -,044 | -,024 | -,044 | ,220 | -,122 | -,529 |

| [12] DPAV (Yes=1; No=0) | -,423 | -,200 | -,423 | -,200 | ,333 | ,200 | -,213 |

Notes: 1 if IFRS are allowed or required for domestic financial reporting, and 0=if prohibited). Significance is at 5% (*) or 1% (**).

There is no single NASS variable that is significantly correlated with allowing or rejecting IFRS for the largest proportion of entities in each country (UNSE, UNCO). NASS design does not seem to affect the political choices regarding the usage of IFRS or, the other way around, the choice of allowing or rejecting IFRS does not have any impact on how the NASS is designed.

This raises some questions. For instance, what are accounting regulation’ decisions based on? For instance, when IFRS 15, IFRS 16, or late changes to IFRS 9 are adopted by the EU they become mandatory for consolidated statements of EU listed companies. How does a NASS decide what to do regarding those new IFRS? Our results suggest that having Advisory and Working Groups, as well as an English annual report are somehow related to those decisions. The negative correlation means that the less those support tools are used, the more IFRS are allowed by NASS. This is consistent with the view that if IFRS are allowed, there is less need for a national adaptation into domestic GAAP, which requires a high technical analysis and often, a difficult political decision.

To illustrate this situation, the Spanish NASS, the ICAC, uses both advisory and working groups. Upon each new IFRS development, there is a deep debate around the decision to adapt domestic GAAP or not. ICAC discloses a large English annual report (88 pages, the third longest in our sample), where it reports activities regarding standard setting. On the other hand, Belgium NASS, CNC, allows IFRS for financial statements of listed entities (both, separate and consolidated), as well as consolidated statements of unlisted and PIEs entities. The CNC does not use advisory or Working Groups and discloses a relatively short (17-page long) English annual report. These two examples illustrate the different level of involvement of NASS in accounting regulation. The ICAC, with a high level of accounting regulation activity and transparency regarding their activities but protecting their sovereignty over accounting regulation for domestic reporting. And the CNC, with a lower level of regulatory and transparency regarding their activities, and a higher degree of acceptance of IFRS for domestic reporting.

6. Discussion and conclusions

This paper has examined the characteristics of national accounting standard setters (NASSs) in 15 EU countries plus Australia and the USA, using a conceptual framework adapted from García et al. (2017). The paper describes and compares the NASSs along four dimensions: nature, organization, financing, and transparency.

Our findings reveal that there are two main models of NASS: a public model and a private model. The public model is more common and consists of a NASS that is hierarchically dependent on a government ministry, mostly funded by public sources, composed of members with public sector backgrounds, and with limited transparency and participation in the due process. The public NASS usually plays an advisory role in the accounting regulation, by issuing opinions or interpretations of international accounting standards or specific transactions. The private model is less frequent and involves a NASS that is delegated by a state institution to regulate accounting standards, mostly funded by private sources, composed of members with diverse backgrounds, and with higher transparency and openness in the due process. The private NASS usually has the authority to issue accounting standards that become effective without further legal approval.

Additional analysis shows that there is not a clear association between the type of NASS and the legal tradition of the country, as measured by the common-law versus code-law classification. Some common-law countries have a public NASS (e.g., Australia, UK), while others have a private NASS (e.g., USA). Similarly, some code-law countries have a public NASS (e.g., France, Spain), while others have a private NASS (e.g., Germany, Italy). We only found a significant association between some NASS characteristics (mainly related to transparency) and one capital market FRQ variable. However, the direction of causality between NASS transparency and capital market information relevance is unclear and requires further investigation. Finally, we found that a substantial majority of countries allow or require IFRS for consolidated financial statements of listed and non-listed companies, but not for separate financial statements. Also, these choices seem to be negatively and significantly correlated with a NASS that uses advisory and working groups or discloses an English annual report. This points at the idea that when a NASS has a more complex organization and due process (by using advisory and working groups, and provides more transparency), it is more likely that the NASS will prefer to regulate separate financial statements with domestic GAAP other than IFRS.

Overall, the paper finds some interesting findings regarding the characteristics of NASS, their policy regarding IFRS adoption, and the potential impact in FRQ. It is striking to find such a great diversity in NASS configurations but having such a high tolerance of IFRS (for consolidated financial statements). In seven countries of our sample, the NASS issues accounting standards for separate financial statements of domestic companies, probably intending to adapt accounting and financial reporting requirements to the specific setting of the country.

Finally, the paper highlights the potential usefulness of the collected data for accounting research that aims to explain or predict differences in FRQ across countries. We argue that the characteristics of NASSs may reflect different institutional factors that influence FRQ, such as legal origin, culture, political economy, enforcement mechanisms, stakeholder interests, and accounting traditions. The paper suggests that future research could use the data to test hypotheses about the relationship between NASS characteristics and FRQ indicators, such as compliance with IFRS, earnings management, value relevance, disclosure quality, audit quality, and corporate governance quality.

These findings contribute to the literature on accounting regulation and standard setting by providing a comprehensive and updated overview of the characteristics of NASSs in different countries and regions. They also have implications for practice and policy by highlighting the diversity and complexity of the institutional factors that shape the accounting environment in each country. Moreover, they offer a valuable source of data for accounting research that aims to explain or predict differences in FRQ across countries.

The paper has some limitations. The study is descriptive and does not provide causal evidence of the impact of NASS characteristics on FRQ or other outcomes. It focuses on 15 EU countries plus Australia and the USA and may not be representative of other countries or regions with different accounting systems or environments. It relies on publicly available information from the NASS websites and annual reports, which may not be complete, accurate, or comparable across countries. Finally, the study uses a limited number of variables to capture the dimensions of NASS characteristics and may not reflect all the relevant aspects of NASS functioning or performance. Future research could address these limitations by expanding the sample of countries or regions covered by this study, collecting more detailed or updated information from other sources, using alternative measures or proxies for NASS characteristics, and conducting empirical analyses to examine the causal effects of NASS characteristics on FRQ or other outcomes. Accounting research could use the data collected in this paper to test hypotheses about the relationship between NASS characteristics and financial reporting quality indicators, such as compliance with IFRS, earnings management, value relevance, disclosure quality, audit quality, and corporate governance quality.

This paper has provided a descriptive and comparative analysis of the NASSs in different countries and regions and discussed their potential usefulness for accounting research. We hope that this paper will stimulate further research on the role and impact of NASSs on financial reporting quality in a globalized accounting environment. We believe that understanding the diversity and complexity of NASSs is essential for advancing accounting theory and practice in a world where accounting standards are increasingly harmonized but not necessarily homogeneous.

Appendix. MISSION per NASS (Dimension 1)

Australia (AASB). The objectives are: (i) to elaborate a conceptual framework to evaluate the accounting standards; (ii) to develop, issue, and maintain accounting standards under the Corporations Act 2001; and (iii) to participate and contribute to the development of a single set of accounting standards worldwide. The AASB issues accounting standards for all Australian entities.

Austria (AFRAC). The objectives are: (i) to research, (ii) document, and (iii) develop accounting and auditing in Austria, considering international changes and national interests. The AFRAC has a General Assembly (Generalversammlung) and a Board (Vorstand). The first one has two responsibilities: (i) economic control of the association and (ii) the election of the President of the Board, treasure, secretary, and auditors. The Board is the authority to administer and manage the association's assets. The Beirat für Rechnungslegung und Abschlussprüfung (Austrian Financial Reporting and Auditing Committee, BfRA or AFRAC) is the main body in the AFRAC’s structure responsible to carry out the technical activities of AFRAC, to issue accounting and auditing standards, and to defend and promote Austrian interests in Europe and at the international level. It also promotes the publication of accounting and auditing work. It was created in 2005. Domestic GAAP are set by law.

Belgium (CNC). The objectives are: (i) to advice the Government and Parliament on matters relating accounting and annual reports, and (ii) to develop accounting regulation by issuing opinions and recommendations to determine legal accounting principles (Belgium GAAP)22.

Denmark (DBA). The Danish Business Authority (DBA) superseded the Danish Commerce and Companies Agency in 201223. In 2007, the DBA delegated the authority to set accounting standards to the Regnskabsudvalget (Danish Accounting Standards Committee, DASC or REGU) which is part of the professional organization FSR (Danish Auditors). Domestic GAAP are established in the Danish Financial Statements Act and the Danish Bookkeeping Act, both issued in the 1980s under the Accounting Directives, with several amendments thereof (Christiansen & Hansen, 1995). Recently, the DBA has established an Accounting Board (Regnskabsrådet) to advise the DBA in accounting matters like regulation changes needed in the accounting acts mentioned before. Overall, the DBA has the legal authority to set accounting standards by amending accounting laws, but it seems to look for advice for the process in the Regnskabsrådet and the REGU.

Finland (KILA). The Ministry of Economy and Employment is responsible for accounting regulation assisted by the Kirjanpitolautakunta (Accounting Council, KILA). KILA was created by the Accounting Board Decree24 (1973) and the Accounting Act25 (1997). The Accounting Act contains Finnish accounting standards. KILA issues (i) opinions and recommendations on the adoption of international standards and the amendments of the Accounting Act.

France (ANC). The objectives are: (1) to issue opinions regarding the adoption of international accounting standards and (ii) to set accounting requirements for domestic companies. Another function is (ii) to supervise the coordination of theoretical and methodological research in accounting to propose opinions and publish recommendations.

Germany (DRSC). The objectives are: (i) to issue opinions and recommendations regarding accounting standards for German companies. In addition, (ii) it represents Germany in international accounting bodies, and (iii) promotes accounting research and education.

Greece (ELTE). The ELTE’s responsibilities include: (i) maintaining a registry of Certified Public Accountants (CPA) and audit firms; (ii) overseeing Institute of Certified Accountants of Greece (SOEL) activities; (iii) providing advice to the Minister of Finance on standards; (iv) developing an investigative and disciplinary (I&D) system; (v) setting ethical requirements for CPAs following proposals made by the SOEL; and (vi) establishing a quality assurance system (QA) for CPAs of all public interest entities (PIEs)26

Ireland. This country does not have a NASS. It does not have local or domestic GAAP either. Companies Act of 2014, requires listed companies to apply IFRS in their consolidated financial statements. In all other cases, companies may choose to apply: (1) UK GAAP, (2) EU-endorsed IFRS, or (3) in certain cases, other GAAP, for example US GAAP.

Italy (OIC). The objectives are: (i) to issue accounting standards, (ii) advise the Parliament in accounting legislation, and (iii) collaborate with European organizations (EFRAG) in the adoption (endorsing) of IFRS.

Luxembourg (CNC). The objectives area: (i) the development of accounting regulation, by issuing opinions and recommendations to the Government regarding financial reporting and representing Luxembourg in international accounting groups.

Netherlands (RJ). The objectives are: (i) to promote the quality of external information of organizations and companies in the Netherlands; (ii) to issue guidelines and interpretations on accounting and financial reporting.

Portugal (CNC). The objectives are: (i) to issue accounting standards for all entities, public sector and private, (ii) ensure the harmonization with international standards, (iii) supervise and control the compliance and enforcement of accounting standards, and (iv) take part in European or international accounting meetings.

Spain (ICAC). The objectives are: (i) the exercise of the supervisory function of auditing (Law 22/2015). Regarding accounting, the ICAC is (ii) the issuer of the Plan General de Contabilidad (General Accounting Plan, PGC), a complete set of domestic GAAP for non-listed companies. It is the competent authority (iii) to assess the suitability and adequacy of any normative proposal or interpretation of general interest in accounting matters with the Conceptual Accounting Framework.

Sweden (BFN). The objectives are (i) to issue accounting regulations regarding the registration and preparation of annual accounts for unlisted companies. In addition, it is under its responsibility (ii) to advise public bodies on accounting matters. Accounting regulation is included in the Annual Reports Act of 1995 (as amended 2016), and Bookkeeping Act of 1999.

United Kingdom (FRC). The objectives are: (i) the regulation of accounting and auditing; (ii) to enforce and ensure the compliance with accounting standards and the control mechanisms to supervise the audit of all entities in the UK. This body is simultaneously the authority of audit profession, quality of audits and accounting and auditing standards and practices.

USA (FASB). The objectives are: (i) to establish and improve the rules of accounting and financial reporting, (ii) to issue accounting standards for listed, unlisted and non-profit companies that voluntarily decide to apply the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP).