The role of agents in accounting reform in the face of the institutional change: The case of the Colegio Universidad de Osuna (1775-1824)

ABSTRACT

This study aims at enriching literature on accounting change by studying the role of the agents in the accounting reform of the *Colegio Universidad de Osuna* (CUO, College and University of Osuna) in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. The paper explores how, in the period 1775-1777, the CUO modified its rules, including its accounting procedures, to prevent its disappearance. Those modifications were aimed at aligning the CUO with the new Enlightenment institutional framework regarding academic requirements and economic rationality. The visitor who prepared the new rules, Miguel Benito Ortega, played a central role in this process. The paper explores the circumstances that favored Ortega\'s role as an agent of change and those that caused the brief and incomplete application of its rules, which contributed to CUO surviving some years but that it would be closed definitively in 1824.

Keywords: Institutional agents; Enlightenment; Accounting reform; Colegio Universidad de Osuna (1775-1777).

JEL classification: B30; M41.

El papel de los agentes en la reforma contable ante el cambio institucional: El caso del Colegio Universitario de Osuna (1775-1824)

RESUMEN

Este trabajo pretende enriquecer la literatura sobre el cambio contable estudiando el papel de los agentes en la reforma contable del Colegio Universidad de Osuna (CUO) en el último cuarto del siglo XVIII. El trabajo explora cómo, en el periodo 1775-1777, el CUO modificó sus normas, incluidos sus procedimientos contables, para evitar su desaparición. Dichas modificaciones tenían como objetivo alinear el CUO con el nuevo marco institucional de la Ilustración en lo que respecta a los requisitos académicos y la racionalidad económica. El visitador que preparó las nuevas reglas, Miguel Benito Ortega, desempeñó un papel central en este proceso. El trabajo explora las circunstancias que favorecieron el papel de Ortega como agente de cambio y las que provocaron la breve e incompleta aplicación de sus reglas, lo que contribuyó a que el CUO sobreviviera algunos años, pero que fuera cerrado definitivamente en 1824.

Palabras clave: Agentes institucionales; Ilustración; Reforma contable; Colegio Universidad de Osuna (1775-1777).

Códigos JEL: B30; M41.

1. Introduction

During the second half of the eighteenth century, Spanish society underwent significant political changes. A 'selected minority' followed the Enlightenment trend of European philosophy,1 which was highly critical of most forms of traditional authority, particularly those related to religion and to the feudalistic exercise of power. Enlightenment thinking sought to replace fear and superstition with the scientific 'Truth' and the establishment of a new social order based on reason, natural law, and political democracy (Sarrailh, 1957). Taking into account the ability of accounting procedures of lending an appearance of rationality to the organisations beyond their actual efficacy (Miller, 1994; Scapens, 1994), Accounting History literature has studied accounting changes implemented during this period in several Spanish organisations (Carmona et al., 1997, 1998, 2002; Prieto-Moreno & Larrinaga-González, 2001; Álvarez-Dardet et al., 2002; Carmona & Gómez, 2002; Jurado, 2002, Llopis et al., 2002; Núñez Torrado, 2002; Maté et al., 2004; Gutiérrez et al., 2005; Rivero et al., 2005; Prieto et al., 2006).

However, few studies have addressed accounting changes in academic organisations linked to the Spanish Enlightenment reform. In fact, studies on Accounting History concerning universities are scarce whatever the period or country. Among the few existing examples, we can mention Covaleski & Dirsmith (1988, 1995), who discussed the role of budgets at Wisconsin State University. More recently, Madonna et al. (2014) applied Foucauldian analysis to the study of the accounting reforms implemented at the University of Ferrara in 1771 and 1824 and showed the influence of papal power on such reforms. For the Spanish case, Martín Lamouroux (1988) studied the accounts of the University of Salamanca in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries; Martín Mayoral (2008) analysed those of the Colegio de San Hermenegildo in Seville in 1643; and Lopez Manjón & Gutiérrez (2006) examined the allocation of expenses and incomes between the College and the University of Osuna in the period 1796-1800.

The study analyses the changes implemented in the administration and bookkeeping of the Colegio Universidad de Osuna2 (hereinafter CUO) during the 1770s from an institutional perspective. The CUO was one of those Spanish minor universities whose survival was threatened by the Government's educational reform developed during the second half of 18th century as part of the changes driven by enlightened leaders.

Delving into this analysis, a significant line of research has focused on the role of individuals who promote institutional change and the conditions and circumstances that favour the adoption of the reforms they promote. In the CUO's case the Duke of Osuna, the patron, send a visitor to the organization with the mission of avoiding its closure. This visitor, Ortega Cobo, had been educated at the University of Osuna and even been its rector in the past, but later, and during the years of the visit he lived and worked in Cadiz, a city with a great presence of enlightened ideas. He drafted two new Constituciones (Statutes) for the College and the University, which were enacted, respectively, in 1775 and 1777. In them, he tried to adapt the CUO to the new institutional framework. However, the limited practical application of the new rules did not prevent the final closure of the CUO a few years later, in 1824.

This paper aims to contribute to the study of the role of agents in the success of accounting reforms linked to enlightenment framework. The case of CUO is characterized by being a typical organization of the previous institutional framework, with a reformer who played the role of bridge between the traditional framework (Old Regime) and the new one (enlightenment ideas), and whose reforms had a temporary and superficial application. Additionally, we contribute to reduce the lack of studies on accounting change in Spanish universities.

We have used in this research a significant body of primary sources found at the Archivo de la Antigua Universidad de Osuna (A.U.O., Archives of the Old University of Osuna).3 We have also used records from the 'Osuna' batch kept at the Sección Nobleza of the Archivo Histórico Nacional (S.N.A.H.N., Nobility Section of the National Historical Archives),4 as well as secondary sources (Merry, 1869; Sancho de Soprani, 1954; Rubio, 1976).

The paper is structured as follows. The next section presents the theoretical framework used; thereupon, we study the scope and impact of the Enlightenment reform on Spanish society and, more specifically, the project to rationalise Spanish universities; and then we examine the history and organisation of the CUO until the crisis that affected it in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. The subsequent section analyses the Ortega's reforms aimed to adapt the CUO to the new framework and the role of the visitor. Finally, the concluding remarks are presented.

2. Institutional theory and the role of agents in accounting change

Institutional theorists have argued that organisations tend to incorporate the practices defined by the prevailing concept of what is rational (Meyer & Rowan, 1977). From an institutional perspective, legitimacy is a condition that organisations need to survive in their contexts and is related to the perceived consonance with relevant rules, their normative support, or their orientation to cultural-cognitive frameworks (Scott, 2001).

Thus, organisations intend to transform their formal structures in line with the powerful institutional rules, reflecting the myths of the institutional environment, rather than according to the demand of their work activities (Miller, 1994). Thus, the basic premise of institutional theory is that successful organisations are those that gain legitimacy by conforming to social pressures (Oliver, 1997, p. 700).

Institutions remain in place through the interaction between legitimised practice and consequent actions (Chapman et al., 2009; Davis, 2017). Over time, actors enact institutional values that lead to practices soon assuming a taken-for-granted status. Within this context, accounting is understood as an element of the 'myth structure' of rationalised societies and, therefore, one of the taken-for-granted means to accomplish organisational ends. Thus, the accountant myth5 is placed on a similar footing to other rationalised professions (Miller, 1994, p. 9), as for example, the military engineers of the 18th century6. Therefore, Accounting is one of the means used by organisations to adopt the rational elements of their context (Meyer, 1986), so the use of certain accounting procedures may confer an appearance of rationality to the organisations (Scapens, 1994). In Fowler's words (2009, p. 172): 'accounting mechanisms (...) can play a dual role both as technique and as institution that conforms to or reflects society's values and norms to achieve legitimacy and hence obtain support and funding.

Thus, Institutional theory provides a framework that tends to give prominence to organisational stability (Greenwood & Hinings, 1996, p. 1023). However, several works explain organisational change in relation to the institutional framework. Oliver (1992) suggested a turning-back process when she defined deinstitutionalisation as 'the delegitimation of an established organizational practice or procedure as a result of organizational challenges to or the failure of organizations to reproduce previously legitimated or taken-for-granted organizational actions' (p. 564). She described three deinstitutionalisation forces: political pressure, functional reasons, and social pressure.

A vast amount of literature has analysed the use of accounting change to adapt the organisations to new institutional environments, as well as to gain or recover legitimacy. Thus, Capelo et al. (2005) indicate how, in the case of the Aguera Commercial House (Cádiz, Spain), the introduction of double entry bookkeeping in the mid-nineteenth century was due to image reasons and the search for legitimacy on the part of the owners-managers. Gomes et al. (2008) examined the mechanisms for the adoption of double-entry bookkeeping by the Portugal Royal Treasury in the mid-eighteenth century. Samkin et al. (2010) showed how annual reports were used by the New Zealand police force to recover institutional legitimacy. For their part, Moreno & Cámara (2014) studied the evolution of the information content in the annual reports of a Spanish brewery company (1928-1993) and concluded that this information changed in response to the pressure of the different institutional environments.

As we have already mentioned, universities have not been a frequent subject of study for accounting historians. Using an institutional approach Covaleski & Dirsmith (1988) studied a university case of the 1980s and showed how societal expectations of acceptable budgetary practices were articulated during a period of decline. The emphasis was placed on the active political agency involved in the process of institutionalising budgeting. Extending the review to other educational organizations we find the work by Fowler (2009), also focused on budgets and educational organisations, that used an institutional approach to analyse changes in primary education centres in Nelson, New Zealand. In this case, the organisations had to adapt to a new institutional environment moving from the non-profit to the public sector. Budgetary changes were intended to obtain a double legitimacy: on the one hand, in relation to the values of the local community, and, on the other, in relation to the Government, which, within this new framework, was the one providing economic funding (2009, p. 189).

To go more in detail into the mechanisms of institutional change, "institutional work" describes this process as divided into three phases: institutional creation, maintenance, and disruption, being the loss of legitimacy part of this third stage. This approach, defined by Lawrence et al. (2009), highlights two issues that are relevant to the analysis of our case. On the one hand, it underlines the loss of legitimacy that the institutions experience during the final phase of the institutionalization process. On the other hand, it invites researchers to focus on the individuals' personal actions, paying more attention to practices and processes (i.e., the why and the how), than to the results (i.e., the what and the when) (Lawrence et al., 2011). This way, it seeks to identify the actors who are more likely to engage in institutional work, the factors that might support or hinder that work (independent of its success or failure), the reasons why certain actors engage in institutional work while others, in similar contexts, do not, and the practices that constitute the range of ways in which actors work to create institutions (Lawrence et al., 2009, p. 10).

Following with the role of agents in institutional change, Battilana (2006) specifies the conditions required for a given actor to be able to behave as an institutional entrepreneur and examines the circumstances in which individuals are more likely to be involved in institutional change. She points out that: i) the individuals' social position is a key variable to understand what their skills are to act as institutional entrepreneurs; and ii) institutional entrepreneurs do not have to succeed in institutionalising new practices to be considered as such, it is enough that they carry out organisational changes that break with the pre-existing institutional logic.

In this line, Battilana & Casciaro (2013) analysed 68 change initiatives in the UK's National Health Service (NHS), an organisation whose size, complexity and tradition could make reform difficult. They concluded that, despite the difficulties, which are especially challenging in large entities, some agents are relevant to the success of the initiative and actually manage to transform the organisations in which they work. In this sense, the network of informal relationships in the organization is often more important than the formal hierarchy.

In this work, we show how a university adapted its academic, economic, and accounting organisation in line with changes in the environment. However, the visitor's attempt to transfer new values to the institution was not entirely successful. Its effects were temporary, and this caused the CUO to ultimately disappear a few years later.

3. The Enlightenment and its project of reforms to rationalise Spanish universities during the second half of the eighteenth century

3.1. The Enlightenment

The Enlightenment was characterised by the critical analysis of the world, philosophy, culture, and religious beliefs. It encouraged the establishment of a new social order based on reason, natural law, and political democracy (Sarrailh, 1957). In fact, all Enlightenment values---critical spirit, faith in reason, confidence in science, educational will---were oriented towards a pragmatic rationality that pursued efficiency (Prieto & Tua, 2012).

These ideas have implications for the case of the CUO. As regards the political context, the educational changes promoted by the Enlightenment rulers were part of their reform program. Considering that the CUO was an aristocratic foundation, the reforms fostered by the Bourbon monarchy certainly had an influence on the organisation herein studied. Among other purposes, the reforms sought to reduce aristocratic power (Vicens Vives, 1974, p. 49) and to articulate that of the royal administration against the nobility in those territories attached to manors (Windler-Dirisio, 1995, p. 79). During the eighteenth century manorialism was undermined, and the lands previously under the control of the nobility were integrated into the nascent state structures. As part of that system, traditional religious universities, did not fit with the ideas of the Enlightenment.

With respect to the Bourbon policies pursuing the centralisation of power in Madrid, accounting played a key role because of the need for accountability in the different territories and peripheral organisations. This led to accounting becoming a key mechanism that facilitated the implementation of centralising measures (see Carmona et al., 1997, 2002; Álvarez-Dardet et al., 2002; Baños et al., 2005).

3.2. The reform of the educational system (1767-1773)

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Spanish universities enjoyed broad autonomy from state power and had a great capacity for resistance when such power tried to intervene in its operation (Álvarez de Morales, 1985). Therefore, Spanish universities in the 1770s were far from the Enlightenment ideal, mainly in what regards the practical applications of education as described in the writings of Enlightenment intellectuals (e.g., Jovellanos) (Sarrailh, 1957, pp. 177-183). Hence, king Charles III requested several experts to draft general and, in some cases, particular reform plans for these institutions. For instance, in 1776 he appointed the expert Gregorio Mayans to prepare a suitable new general curriculum for the Spanish universities (Domínguez Ortiz, 1988). Another one of these reform plans was signed by the enlightened Pablo de Olavide, who implemented it at the University of Seville in 1768. The initial description of the present situation included in this plan evidences the bad opinion that the intellectuals of this period had about these educational institutions in Spain. Olavide wrote that they 'had become frivolous, inept establishments, concerning themselves only with ridiculous questions, unbelievable hypotheses, and false distinctions, and that they had abandoned the solid knowledge of the practical sciences, which alone showed the way to obtain useful inventions' (Aguilar Piñal, 1989, p. 82).

One major problem was the existence of too many minor universities, often controlled by the Church or the nobility, with different curricula and usually low academic requirements (Álvarez de Morales, 1985; Domínguez Ortiz, 1988). Besides, the low salaries paid to the instructors hindered their full-time dedication to the University.7 Sarrailh (1957, p. 98) described professors as reluctant to any reform8 and added to the list of difficulties the frivolity with which many students, specifically the noblemen, lived their university years, devoting themselves to the social life that the University provided rather than to academic matters (p. 88).

The new norms set by the Council of Castile entailed the implementation of reforms in at least three key aspects of university activity: the academic standards demanded for the award of degrees; the curricula to be taught; and the level of qualification and commitment required from instructors and professors.9 As a result, Spanish universities reformed their curricula from 1772 onwards, with a variable degree of resistance to change, different levels of innovation, and frequent economic difficulties to carry out the reforms (Álvarez de Morales, 1985).10

A key aspect of the eighteenth-century Spanish educational reform was the expulsion of the Jesuits from the country in 1767. At that time, the Society of Jesus exercised a great influence on education.11 Because of its ideology, the Society was accused of supporting the most conservative 'collegiate faction'. The subjection and later expulsion of the Society of Jesus presented a double advantage for the Enlightenment Government: it reinforced the power of the State and facilitated the dissemination of the new ideas.12

4. The CUO until the crisis of the last quarter of the eighteenth century

4.1. Foundation and organisational structure

On October 10, 1548, in response to a petition from the fourth Count of Ureña,13 Pope Paul III (1468-1549) promulgated a papal bull authorising the founding of a university in the southern Spanish town of Osuna (see ). One of the privileges of the Spanish aristocracy during the Ancien Régime had been the right of foundation, which allowed noblemen to promulgate the rules of an institution and appoint its staff in return for economic support Atienza (1987). According to the literature, one of the objectives of founding the CUO was to contribute to the Counter-Reformation by improving the clergy's training (Merry, 1869; Sancho de Soprani, 1954; Rubio, 1976). This, together with the papal authorisation to the foundation and the fact that most chairs were held by members of religious orders, proves the religious character of the institution.

Map 1. Location of the town of Osuna in the Kingdom of Seville, Spain, Eighteenth Century

Additionally, the deed of foundation of the University established the creation of a residential College attached to it. This College was the residence of the University staff and students and was run according to a monastic regime. There were numerous interrelationships between the College and the University, despite their being independent institutions. This is the reason why we address their developments separately, although there are certain factors that make the separation difficult. Consequently, we will talk about the CUO, and only when a question affects exclusively the College, or the University will we refer to them as individual centres.

According to the founding papal bull, the University was a private foundation under the power of its patron; he had only to comply with the canon law and with whatever degree of autonomy he might wish to grant to the organisation through the drafting of its Constituciones (Statutes) (Rubio, 1976). Usually, the patron did not take part in the management of the CUO, although he could send visitors to control the centres. When necessary, the visitor would draft a set of new rules that had to be ratified by the patron.

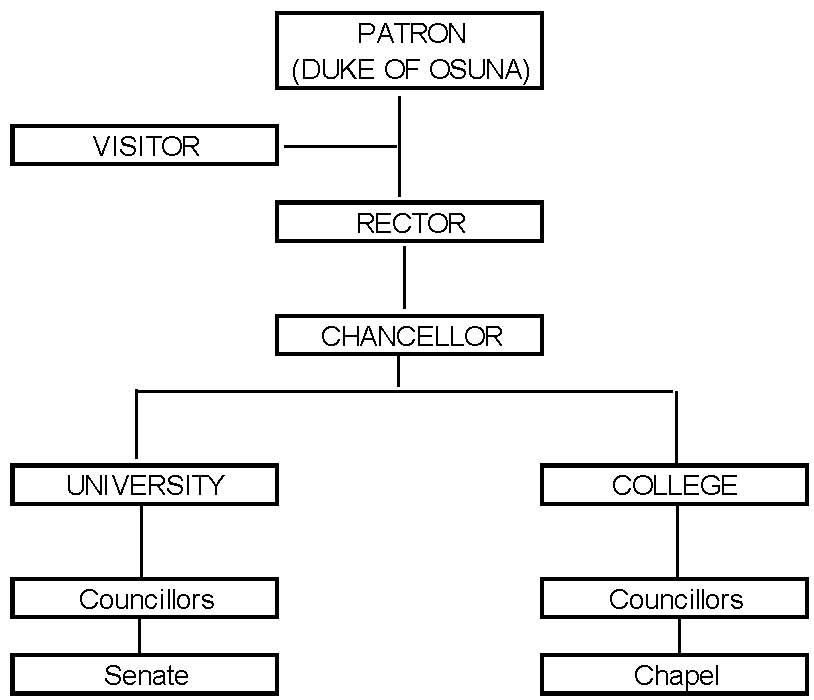

Figure 1. Organisational chart of the College-University of Osuna

Source: Own elaboration with data coming from A.U.O.

The rector governed and exercised the ultimate judicial and academic authority over the CUO. As in all institutions of ecclesiastical origin, a chancellor represented the authority of the Church, ensuring compliance with the rules promulgated by the ecclesiastical hierarchy and acting as a judge of appeal. The College and the University separately elected their consiliarios (councillors),14 who served one-year terms as assistants to the rector. In addition, each institute had a governing board. In the College, this board, known as the capilla, took the form of a collegians' assembly chaired by the rector; in the University, it was the Senate. Figure 1 shows the organisational chart of the CUO. Because of the small number of University students and collegians, most of these positions were spare-time ones.

4.2. Economic issues

The main income sources of the CUO were the revenues granted by the patron in compliance with the deed of foundation.15 These consisted of various ground rents,16 taxes, privileges, and renting contracts provided by the duchy. In addition, the patron made other periodic contributions. Among the most significant ones, we can mention the supplies of wheat sent as provisions for the collegians; the transfer of the ownership of a country property17 in 1604; the payment for the mass celebrated on the anniversary of the foundation;18 and the direct payment of part of the instructors' salaries from 1777 onwards.

The University also generated certain incomes such as the fees the students paid to acquire their degrees19 or the payments made by professors upon taking possession of their chairs. The degree fees represented the only contribution made by the students to support the University, since they did not pay any enrolment fees or regular tuition fees. These funds served to cover expenses such as the payments to which professors were entitled for attending degree-awarding ceremonies or the celebration of solemn masses. There were occasional donations made by students, ex-students, or ex-collegians, although the amounts involved were never significant.20 In addition, some occasional donors included the CUO as beneficiaries of their wills.

Regarding expenses, the main one the College had to face was the purchase of food and provisions for the rector and the collegians, which were usually paid monthly. According to the foundational Statutes and subsequent reforms, food expenses usually took the form of supplies of goods. As for the University, its expenses consisted mainly of the salaries of the professors and other officials, and the obligation to pay for certain religious services specified in the Statutes or celebrated on special occasions21.

4.3. Administrative procedures and bookkeeping prior to the mid-eighteenth-century crisis

The CUO rules in force until the outbreak of this crisis dated from the first third of the seventeenth century. The fourth Duke of Osuna, Don Juan Téllez Girón (1597-1656), managed to resolve a controversy over the administration of the common estate, i.e., the common accounts, of the College and the University. He got both parties to accept the Royal Provision of 25th November 1628,22 which, not only determined how the common flow of revenues should be shared between College and University, but also contained the basic strategy for the government of the organisation.

The key elements of this new administrative scheme were four. First, the financial affairs of the University were the responsibility of the rector, two chaired professors annually nominated by the Senate for this task, and a delegate of the patron. Second, the rector, the collegians and a representative nominated by the patron were in charge of the economic matters related to the College.23 Third, a single collector was appointed effectively as the cashier for both institutions. He was accountable once a year to both groups of governors in the presence of the duke's agents. Fourth, the patron and his successors could, however, modify any of these provisions at their will.

The Royal Provision was issued while the Franciscan friar Tomás Muñoz de Espinosa, qualifier24 or auditor of the Holy Office in the city of Cordoba, was visiting the College and University, between the years 1627 and 1631. When his visit concluded, he drafted two Statutes: one for the College and one for the University, both of which were ratified by the patron on 11th December 1632. These documents confirmed the stipulations of the Royal Provision of 1628 and detailed the administrative procedures of the CUO.

According to these Statutes, the people responsible for managing the administrative and financial system of the CUO continued to be the rector, the collegians, the patron's delegate, and the collector, in the case of the common estate. This fund was used to pay the main expenses of both the College and the University. On the other side, the rector, the two professors nominated as administrators, and the treasurer were responsible for the revenues and payments specifically generated by the University.

Regarding the submission of accounts, the normative drafted by Muñoz regulated the frequency and the people required to do it, including the collector, the rector and the governors, who were accountable to their successors, the treasurer of the University, who was accountable to the governors, and whoever was designated by the board (capilla) of the College or the Senate of the University to carry out any specific task, whenever they finished their mission.

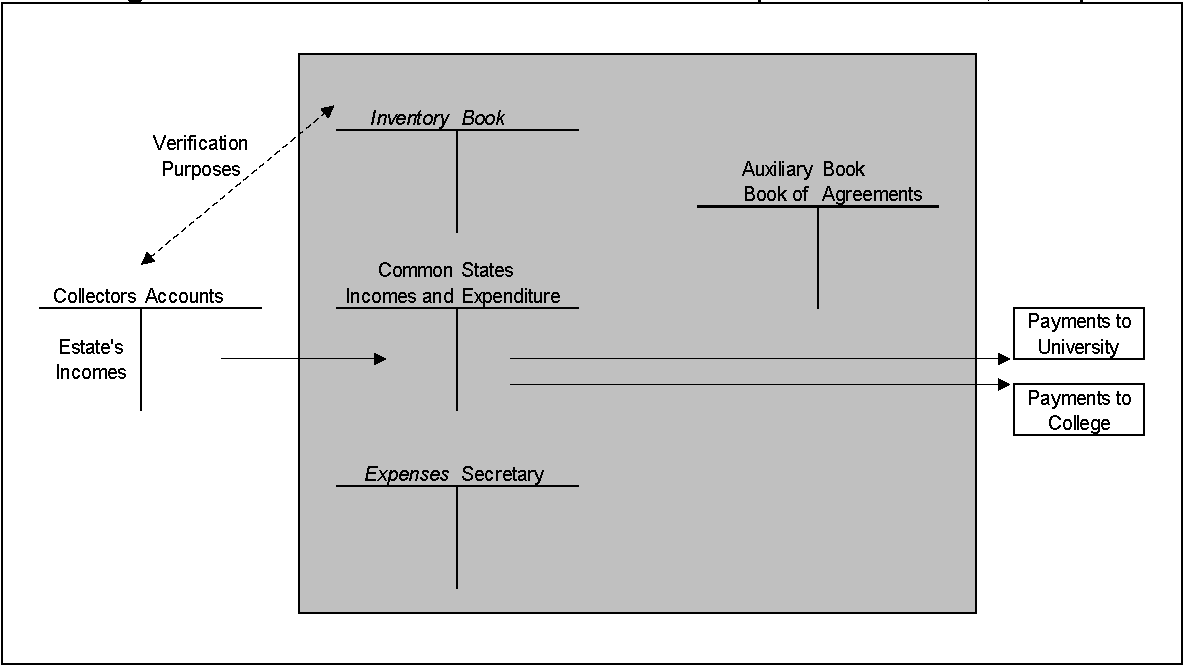

With regards to the accounting books, the following had to be kept: i) a book of income and expenditure of the University, kept by the treasurer; ii) another book of expenses of the University, kept by the secretary; iii) a book of agreements or resolutions adopted at the administrative meetings, which may be assumed to include the accounts submitted by the accountant; and iv) a book containing the inventory of the estate (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Informative accounts and flows (Tomás Muñoz, 1632)

Source: Own elaboration with data coming from A.U.O.

On the other hand, two types of meetings were established to deal with administrative and financial issues: one with the rector and the chaired professors, every two months; another one with the rector and the administrators, at least three times a year.

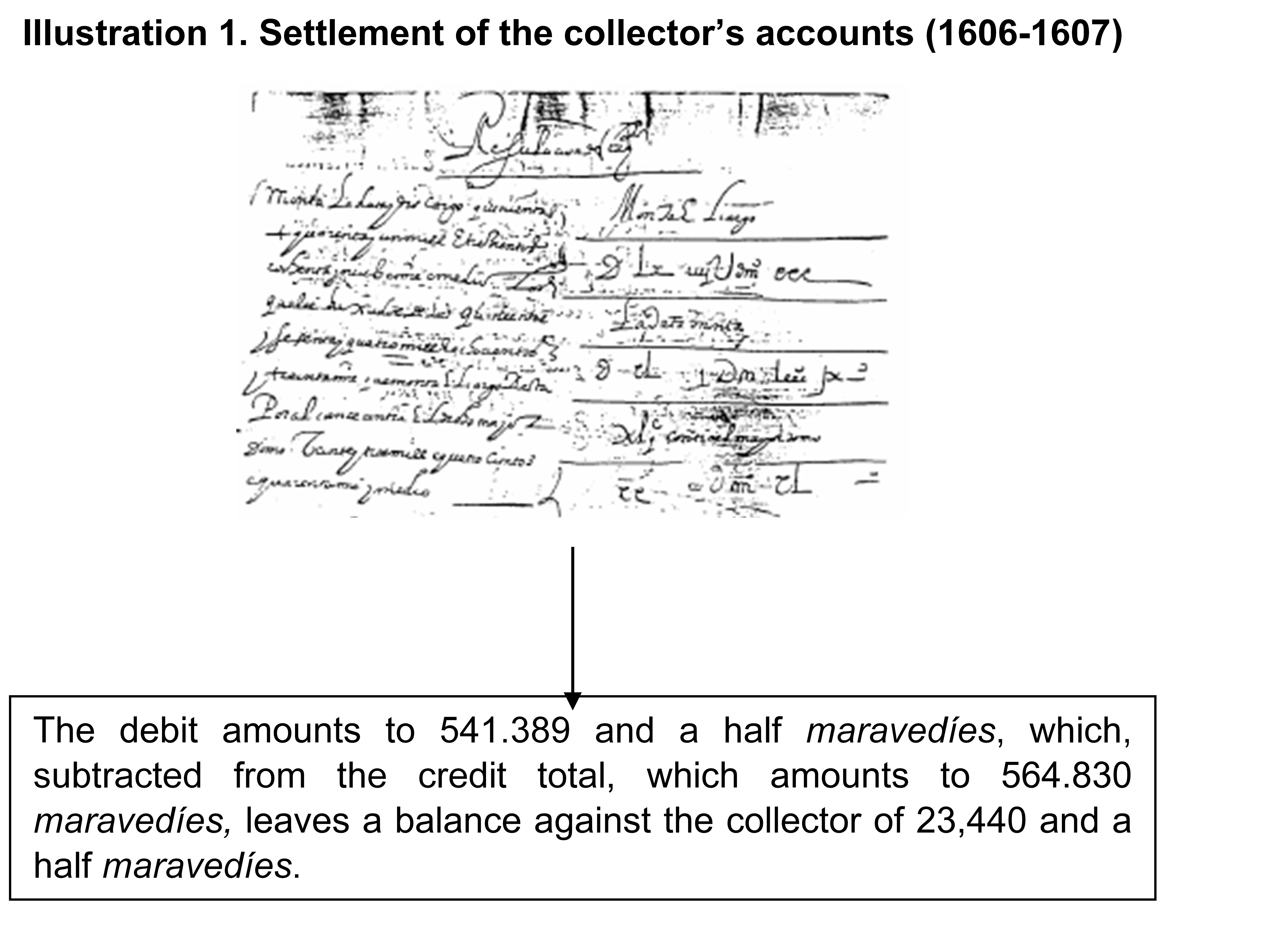

The archival evidence informs us that the College and University collectors submitted accounts by the 'charge and discharge' system, at least from 1604 onwards.25 The charge included all collections from the properties and rights of the College and University estate. The discharge included the amounts paid by the collectors on behalf of the institution. They were, mainly, the University staff's salaries and the rector and collegians' maintenance costs. This format was used for the settlement of accounts without remarkable changes until 1754. shows, as an example, the final adjustment of the accounts for the period 1606-1607 filed by the collector.

The oldest accounts filed by the University treasurers kept in the A.U.O. date back to 1684.26 They were kept using the 'charge and discharge' system and covered a one-year period. Attached to these accounts, there is a list of the amounts deposited in the University safe until 1720. From that year onwards, the quantities were registered in a specific book for such purposes.27

Between 1754, while Miguel Benito Ortega Cobo was rector of the CUO, and 1774, a 'safe' substituted the 'collector' as centre of the accounting process and subject of accountability, so that the accounts were now based on the cash movements, which were settled at monthly meetings. This accounting system was known as clavería28 (A.U.O., prov. refs. 100 and 620-622). The change improved cash security during the process, because now the collector deposited and received the money every month and was never in charge of it for more than thirty days. From 1755 onwards, primary sources confirm the use of an income and expenditure book29.

Illustration 1. Settlement of the collector's accounts (1606-1607)

5. The CUO and the Enlightenment reform

5.1. The threat of closure

The orders calling for the implementation of the University reforms were communicated to the CUO by post (see Table 1). The successive letters contained detailed information on the courses or procedures to be reformed, such as the curricula, the requirements for the award and validation of degrees, the competitive examinations to fill teaching positions, and the nomination of a royal supervisor.

The curricula and teaching methods of Spanish universities in the eighteenth century reproduced the schemes used in previous periods and were far from the Enlightenment ideas. In order to get acquainted with the situation at the University of Osuna in 1767 the Government asked the reformer of the University of Seville, Pablo de Olavide, to draft a report about the CUO, which was transcribed by Aguilar Piñal (1969, pp. 460-461)30. He was critical of the following aspects: (i) the lack of a procedure for appointing professors due to the fact that 'the patrons awarded the positions without any proper competitive examination or comparative judgement between candidates'; (ii) the professors' frequent absenteeism and the lack of students: '[...] the deserted classrooms for lack of both pupils and masters'; (iii) the low academic standards: 'They awarded degrees without any proof of aptitude [...] and what is even more deceitful: the abuse of selling these qualifications of distinction that has been detected'; and (iv) the bad economic situation of both institutions: 'In spite of several subsidies [...] the income today has fallen to only 17,190 reales, 6,876 assigned to the University to pay its own expenses, with the professors sharing 3,800 reales among all of them'. The amount mentioned by Olavide represented only 54% of the sum initially donated by the founder (López Manjón, 2004).

Table 1. University reform measures read at the Senate meetings of the University of Osuna

| Date | Topic |

| 1767, May 6 | Expulsion of the Jesuits. |

| 1767, May 20 | Obligation to teach the rules of the Council of Constanza prohibiting the killing of kings or tyrants. |

| 1767, October 7 | Reiteration of the order prohibiting the establishment of turns to hold university chairs promulgated on December 22, 1766. Request for reports on the procedure for filling chairs and on the number of chairs in each university. Reminder of the obligation to hold open and previously advertised competitions for the granting of chairs. |

| 1768, August 24 | Abolition of the chairs of the Jesuitical School. |

| 1770, March 5 | New requirements for the granting and validation of degrees. |

| 1770, December 1 | Abolition of the exemption from military service for students of the University of Osuna. |

| 1771, January 19 | Closing of the University of Osma (in the province of Soria) and prohibition of validation of its degrees. |

| 1771, April 4 | Prohibition of validation of degrees obtained in colleges, seminaries, and monasteries. |

| 1771, December 23 | Ratification of the abolition of the chairs of the Jesuitical School. |

| 1772, January 15 | Prohibition of the simultaneous study of two branches of theology. |

| 1773, May 23 | Requirement that each university send the Government a short list of three candidates to fill the position of Royal Manager of the University. |

Source: Own elaboration with data coming from A.U.O.

Moreover, according to Olavide, this University was unnecessary, because 'facilitating the pursuit of studies by the sons of labourers and craftsmen would end up ruining their parents and causing losses to both agriculture and the crafts' (op. cit., p. 200).

Given the bad situation of the University, the Senate asked the Crown for financial support on May 8, 1767. However, this petition displeased the duke, who sent a letter to the Senate, read at the meeting of November 4, 1767, in which he reminded the professors of his full authority, as patron, over the centre and stated that he should be its only financial supporter. This attitude is understood because the University was a symbol of prestige for the duchy. Three years later, in 1770, the duke promised to endow the foundation with the necessary chairs to promote it.

A royal order to close the University of Santa Catalina, located in El Burgo de Osma and similar to Osuna's minor university31, and Olavide's unfavourable report explain why the Senate of the University of Osuna felt that its own closure was imminent. This was proved by a letter sent to the patron and read at the Senate meeting of February 6, 1771:

This Senate, afraid that this may be the last time we have the opportunity to appeal to Your Excellency in such capacity [...]. As a minister remarked to a member of this Senate, the total income of the University and College combined amounts to what one professor holding a single chair should earn [...] the best-endowed chair amounts to only 3032 ducados33 [...] it is necessary to take measures... [emphasis added]

5.2. The CUO's response to ensure its survival (1775-1777)

Adapting to the new legal framework required that the CUO implemented a major reform, which made necessary the promulgation of new Statutes. The patron entrusted the reform to a former rector and collegian of the CUO, Miguel Benito Ortega Cobo, who drafted a new regulation including academic, administrative, and accounting changes. Miguel Benito Ortega Cobo had been canon penitentiary of the Cathedral of Cadiz between 1764 and 1787, also occupying the positions of synodal judge, as a specialist in canon law in charge of examining the candidates to enter a religious order or any sacred ministry, and episcopal vicar.

Besides, Ortega lived in one of the cities with the largest commercial concentration in Spain at the time and was acquainted with the accounting techniques in vogue during that period.34 Particularly, the Bishopric of Cadiz was involved in the reformist ideas of the enlightened age, especially following the appointment of Bishop Servera. Thus, for instance, the Bishopric promoted the creation of Sociedades Económicas de Amigos del País (Economic Societies of Friends of the Country) in its territory.35 During the time in which Ortega served in the Cathedral of Cadiz, the Bishopric transitioned from a traditional ecclesiastical model, based on asceticism, devotion, indiscriminate almsgiving, or the defence of the Church's jurisdiction, to the establishment of an ecclesiastical hierarchy that collaborated with the Government to encourage cultural, social welfare and economic development in favour of public interests (Barrio, 2002).

In his foreword to the new Statutes (Constituciones of the College: A.U.O., prov. ref. 237; Constituciones of the University36), Ortega described the internal situation of the College in the middle years of the eighteenth century as deplorable, in consonance with Olavide's opinion.

5.2.1. Academic reform

With regard to academic affairs, Ortega dedicated one chapter of his Statutes to mention the authors to be studied in each course and school, adapting the requirements to the new directive of the Council of Castile, accepting its authority to introduce changes in the curricula. The requisites for students to enrol in the various courses, and to obtain the corresponding degrees became stricter. Thus, the student had to be in possession of a 'sworn certification to prove that he has attended the necessary courses, issued by his professors, countersigned by the rector and authorised by the secretary, either of this University or of any other approved university of the Kingdom' before sitting for the exams to obtain a degree (clause 46 and following). The Statutes prohibited excusing any student from performing any of the practical training necessary to obtain the higher degrees (clause 54), and, to qualify in Medicine, students had to prove they had had a two-year practical training (clause 46). Other examples of the tightening of the academic standards were: i) the requirement of a sworn certification before the second year confirming the student's continuity of attendance and regular progress, at least in the previous year's course (clause 6); ii) the prohibition of repeating a course more than once; and, moreover, iii) the exclusion of the students' participation from the election of professors for a chair and from the selection of textbooks.

To fight against professor absenteeism, Ortega imposed a sanction that reduced by one-third the salary of the instructors who did not attend their duties regularly.37 The only measure established by the Council of Castile that Ortega did not include in his rules was the open public competition to fill vacant chairs. Doubtless, at the patron's behest, the visitor maintained the de facto authority of the patron to appoint the chair holders.

An academic measure with economic implications was the reduction to 17 of the number of chairs. Ortega assigned annual salaries to the chairmen that ranged between 60 and 100 ducados.38 These new salaries were far from the 700 ducados per annum proposed by Olavide in his plan for the reform of the University of Seville, but they meant a significant increase over the amounts paid to the professors at Osuna in previous years, considering that the salaries fluctuated between 22 and 30 ducados in the period between 1771 and 1776.39

5.2.2. Administrative and accounting reform

Ortega's administrative and accounting reform was aimed at making an unselfish and appropriate use of the CUO's resources, and proving it was so. Ortega drafted two Statutes, one for the University and another one for the College. The first one included the economic regulations concerning the wealth shared by the two centres and the University's exclusive economy. Regarding the common estate, article 12 of the new Statutes established that the rector, the collegians, two professors40, and the patron's delegate would all be in charge of managing the common funds. They had to meet at least once a month, while previously there had been but one annual meeting (López Manjón, 2004), and the collector would inform them of whatever was necessary, while the accountant, who had to be a local notary public, recorded the minutes of the agreements reached during each session.

The collector had to render the annual accounts within two months after the end of the calendar year. The accountant was responsible for preparing and reading the accounts. The collector was also responsible for depositing in a safe, at the end of each administrative meeting, the amounts collected each month. The safe would have two keys, one held by the rector and the other one by the professor in charge of the administration.

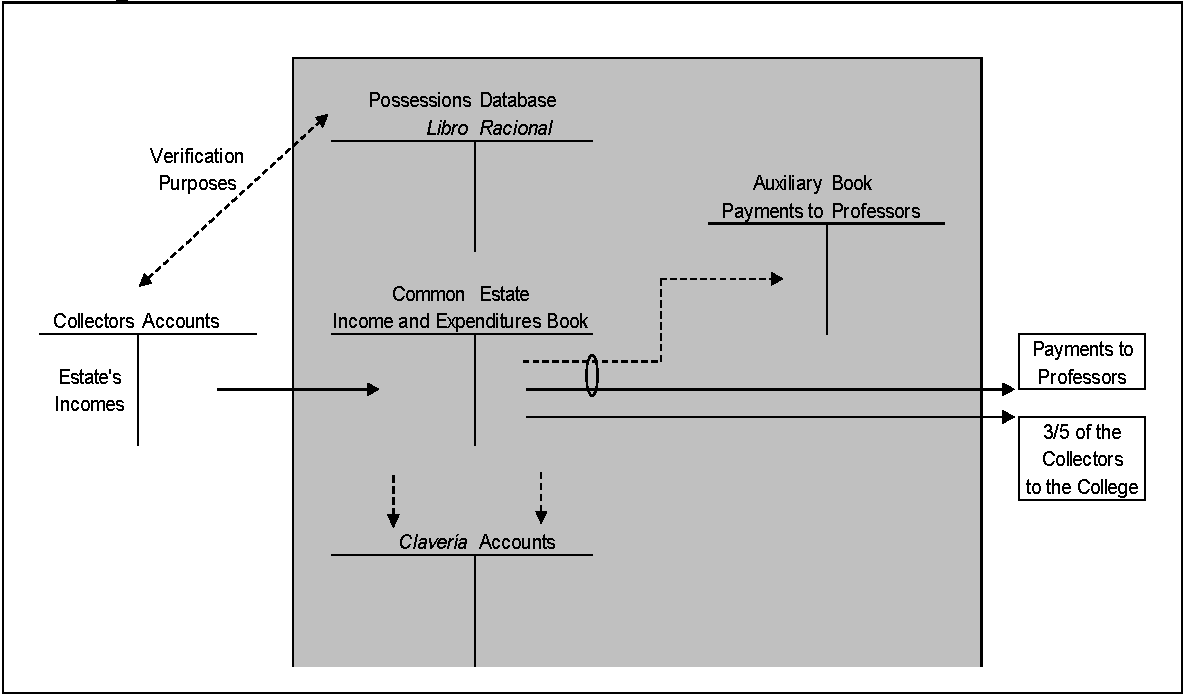

Ortega's Statutes increased the influence of the patron's delegate on the management of the institution. He had to sign the payment orders and had the casting vote at the administrative meetings. The accounts had to be reported to the rector, the administrators, the patron's delegate, and three University deputies elected to collaborate in administrative tasks. These people would be responsible for the inconvenience caused in case the accounts were not settled within the prescribed term. Figure 3 shows the information flows concerning the common estate as established in Ortega's Statutes.

Figure 3. Network visualization map of the co-occurrence of keywords

Source: Own elaboration with data coming from A.U.O.

As for the University, the Statutes determined that the rector, two professors and the collector were in charge of managing its funds. They would meet as a board at least twice a year. The treasurer of the University, who was responsible for its goods and valuables, received the payment of fees and gratuities and paid the expenses associated with official duties and University events. Every year, the Senate appointed one of its members as treasurer, and he was obliged, as was the collector, to swear before a public notary that he would fulfil his tasks. In addition, every year the Senate elected two new councillors who, together with the rector, issued the University diplomas and received the accounts drawn up by the treasurer before the start of the following year. The secretary of the University had to be present at the delivery of the accounts. He also kept an income and expenditure book that served to cross-check the data presented by the treasurer. Once submitted, these accounts were passed on to the Senate for their approval.

As the University could not face the considerable increase in expenses due to the rise in the professors' salaries, the patron's financial contribution became necessary and in 1777 the duke promised to pay one-third of these salaries.

According to the evaluation of the University chairs during that period, salaries increased an average of almost 87% between 1771 and 178041. With respect to the College, article 26 of the new Statutes, approved on May 5, 1775 by the Duke of Osuna,42 described the management of its accounts as follows:

A strong chest will be made with four locks, the keys to which will be held, respectively, by the rector, the two councillors, and the person designated for this purpose by the patron [i.e., the patron's delegate]. This is where the funds held in common with the University will be safeguarded, under the care of the depositor43 himself. [emphasis added]

The same article specified how to use the funds kept in the safe: at the beginning of each month, the regular amount required to pay for the food consumed at the College would be withdrawn. The rector had to keep a notebook in which he recorded the monthly expenses. No additional money could be withdrawn until the legitimate use of that amount was justified and registered in the book and only in case of necessity, the safe could be opened before the end of the month. Every year, the administrators had to report on the money that was put in and out of the safe. The accountant of the CUO was responsible for preparing the accounts, which were signed by him, the rector, and the key-holders, registered on a specific book and, finally, sent to the patron with the attached receipts.

Ortega's reforms also included some measures aimed at controlling the College's expenses, such as certain restrictions on medical expenses (article 32), the obligation to eat at the College, the prohibition to claim for the expense on food in cash (article 32), the restored non-obligation to pay for clothes (article 73), or the limitation on the number of servants each student could have supported by the College's income (article 16). At the same time, the Statutes included a new position, that of the larder-dispenser, who was in charge of the daily expenses and received money for this from the youngest collegian, being accountable to him for the number of persons eating at the College daily and for the amount spent on their food (article 20). These procedures required the use of eight accounting books.

In addition to these measures, Ortega introduced other control mechanisms, such as (i) the increase in the power of the patron's delegate; (ii) the geographical concentration of the estate by demanding new leases to be within Osuna's municipal area; (iii) the requirement that property lettings be done by public auction in the presence of the accountant; (iv) the introduction of a document intended to control the debits of previous accounts44; and (v) the obligation to safeguard the documents related to the estate of the two institutions in an archive locked with three keys. The University had a safe for its own particular purposes. Copies of both inventories had to be sent to the patron.

6. Analysis: A reform deeper in the rules than in daily practice

Table 2 compares the control measures imposed by the two sets of reforming Statutes, those drafted by Muñoz (1632) and those by Ortega (1775-77). The data are arranged in this table so that they can be easily compared:

Table 2. Improvement of the control measures from Muñoz’s to Ortega’s regulation

| MUÑOZ’S STATUTES | ORTEGA’S REFORM (Changes are indicated) | |

|---|---|---|

| Administrative books |

|

|

| Safes (chests) for: |

|

|

| Accountability on: |

|

|

| Administrative meetings |

|

|

Source: Own elaboration with data coming from A.U.O.

In addition to the measures included in this table, there were other control mechanisms introduced by Ortega, such as the concern with the objective of ensuring the geographical concentration of the estate, requiring the renewal of leases only within Osuna's municipal area, and a document intended to control the debits of previous accounts.45

In what concerns the disclosure to the stakeholders, CUO continued to be accountable only to its patron, the duke, whose representative gained power with this reform. In fact, the text of the Statutes includes as an aim of the administrative restructuring that the 'College will hold irrefutable testimony of its disinterested behaviour in the management of its income, and greater confidence to request, should this be necessary, food from His Excellency the Lord Patron (article 11 of the Statutes).

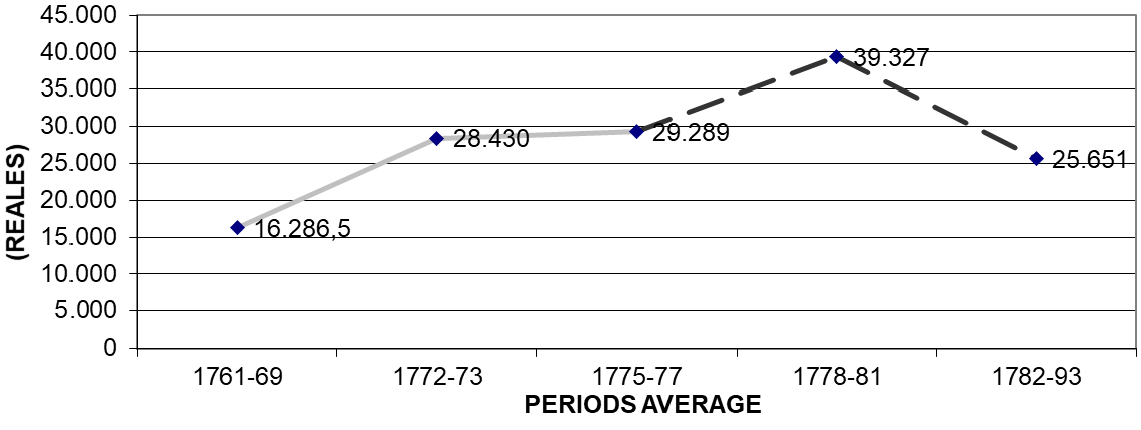

The accounting records also prove the short-lived success of the improvements of the financial control mechanisms. Thus, an increase of over 34% was obtained in the total amounts collected by the collectors between the periods of 1775-77 and 1778-81, but the amount fell again shortly thereafter, even below the previous level (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Amounts Collected by the Osuna's College and University Collectors, 1761-1793

Although this system did not completely coincide with the one proposed by Ortega's reform, it involved a parallel use of the collectors' accounts, as well as of the clavería accounts and the book of income and expenditure and recorded the deposits and withdrawals from the safes.

After analysing the changes produced, we can say that the Ortega's accounting reform was rational and in line with the Enlightenment ideas but was not fully adopted. The Statutes demanded the simultaneous use of the clavería and the collectors' accounts. However, in reality, the clavería accounts were not used ---although an income and expenditure book was indeed kept for the safe---, and the deadlines to present the reports were not met.

Actually, from 1775 to 1792, the collector's accounts46 varied somewhat from those presented until then, even if no clavería accounts were compiled. The most important new data recorded was the increase of just over 27% of the amounts received and deposited in the safe. As the deposits in the safe were in fact the discharges of these accounts, details about the destination of those amounts stopped being recorded, whether they were used to pay the salaries of the University's professors and officials or the food provided to the collegians, which were the main expenditures registered in this period on the book of income and expenditure. The collectors did not meet the obligation of reporting their accounts annually. For their part, the University treasurers continued submitting their accounts every year until the closing of the centre in 182447. Therefore, although Ortega tried, his administrative reform did not mean an actual improvement, given its limited practical application.

The literature has pointed out how the entrepreneurial agent's social position (Battilana, 2006) and his informal network of relationships within the organization (Battilana and Casciaro, 2013) are factors with relevant influence on the success' chance of the reforms promoted by the agent. In the case of Ortega Cobo in the CUO, his social status as a member of the ecclesiastical hierarchy, his condition as former rector and the support of the Duke of Osuna were points in his favor to achieve the implementation of the reforms. However, the temporary nature of its position in the CUO hierarchy, since it was not a permanent authority, and its limited capacity to maintain informal networks within the center, or to carry out a close monitoring of compliance with the rules, played in favor of the early relaxation of its observance. Neither the Duke nor the visitor had direct or frequent contact with the CUO, and the organization was not even accountable to the visitor after his temporary task was over.

Ortega met the conditions required to be considered as an institutional reformer (Battilana, 2006). Since, although he did not manage to fully institutionalize the practices that he designed, he achieved organizational changes that broke with the pre-existing institutional logic. Consequently, this case complements previous studies (see Battilana, 2006), in the sense that some enlightened reformers of the Spanish 18th century, although did not always have successfully completed their reforms, did break with some logics of the Old Regime.

7. Concluding remarks

The participation of Enlightenment thinkers in the government of Spain and the implantation of new ideas in Spanish society led to the development of a new institutional framework (Miller, 1994), based on principles such as 'Reason' and 'Truth' (Meyer, 1986). This new context saw the emergence of social and political pressures---two of the three deinstitutionalisation forces quoted by Oliver (1992)---against certain organisations, such as Spanish minor universities, frequently associated with the aristocracy or the Church. The CUO was an example of a minor university sponsored by an aristocrat and with a strong religious character, so the change of the institutional framework represented a threat to its survival. The CUO's reaction to the new situation was a reform of its Statutes implemented by Miguel Benito Ortega Cobo. Ortega's reform tried to instil new values into the CUO, including: (i) the development of rational thinking among the students, in accordance with the enlightened ideas; (ii) a more rational management of the CUO; and (iii) an improvement of the maintenance and wellbeing of the students.

As in the case of budgetary changes implemented in primary education centres in Nelson, New Zealand (Fowler, 2009), the CUO reform faced a double challenge in its attempt to recover legitimacy. The CUO needed to legitimise and prove the validity of its teaching activities in the eyes of the Government in order to avoid its closure, but also in those of its patron for the purpose of obtaining an increase of his financial support.

In order to legitimise the CUO vis-à-vis the new educational policy, Ortega's Statutes included the new regulations of the Council of Castile concerning such academic matters as the curricula and the standards required for the awarding and validation of degrees. This implicit recognition of the new legitimising source is not new in the literature on accounting change in universities during the same period (see Madonna et al., 2014).

Ortega used accounting to introduce the rational elements of the new context in his reform (Meyer, 1986; Scapens, 1994) in order to achieve legitimacy, and hence obtain support and funding (Fowler, 2009). In this case, Ortega improved the available instruments of financial control to legitimise the CUO in the eyes of the patron.

However, despite the visitor's intention, those changes were not fully adopted. Some accounting changes included in Ortega's reform were abandoned a few years after the promulgation of the new Statutes. In addition, the organisation soon failed to fulfil the new requirements. In other words, the CUO did not in point of fact adapt to the new institutional framework, because it did not internalise the Enlightenment values (Oliver, 1992; Capelo et al., 2005).

Following the ideas pointed out by Battilana (2006) and Lawrence et al. (2009, 2011), our study concludes that Ortega, despite the lack of full success in the institutionalisation of his reform, was an institutional reformer who designed an accountability process for the CUO that was in line with the enlightened values of the last third of the 18th century.

As argued by Battilana (2006), institutional reformers do not have to be successful in the institutionalisation of new practices; it is enough that they carry out organisational changes that break with the former institutional logic for them to be considered as such. Therefore, the group of reformers of 18th century must not be limited only to a few great enlightened reformers but must "open up" to many other agents with more limited scope of action that the literature has hardly recognized.

Ortega's capacity as an institutional agent was reinforced by his social status (Battilana & Casciaro, 2013) since he held a relevant position in the hierarchy of the Church and had previously been rector of the CUO. Therefore, the Visitor's capacity to influence was derived more from his social status than from his position in the formal hierarchy of the organization.

However, the transitory nature of its passage through the CUO, and the lack of subsequent vigilance of its reforms influenced the fact that these were applied just in temporary and incomplete way. Thus, we can conclude that the lack of vigilance of new rules, and the fact that they are prescribed by staff-type bodies not included in the organization's permanent formal hierarchy are factors that hinder the internalization of the reforms.

Ortega's reform functioned as a 'bridge' meant to transfer the institutional values of the Enlightenment to a typical educational centre of the Ancien Régime. The reformer had been born in Osuna, and had studied and been rector of its University, so he was well acquainted with the aristocratic values of this institution to which he was emotionally linked. In other words, he had been brought up and trained academically in an environment that was in crisis at the time of his reform. Nevertheless, he was also knowledgeable, due to his contact with various organisations in Cadiz, of the new enlightened ideas. This duality of being a person interested in the survival of the CUO, and at the same time influenced by the values of the Enlightenment, made him the institutional actor who attempted to adapt the CUO to the new institutional framework according to the mission that was entrusted to him. Nevertheless, at the same time, his reform respected some privileges of the duke, such as his right to assign chairs, and held CUO exclusively accountable to the duke.