Mind the Gap in Financial Inclusion! Microcredit Institutions fieldwork in Peru

ABSTRACT

Financial inclusion remains a key political issue. Since microcredit first captured public attention, Microfinance Institutions (MFIs) have expanded rapidly all around the world. Although much economic and financial literature has highlighted the importance of microfinance as a factor of development, there is also an intense debate about its effectiveness as a development tool. This paper is a descriptive analysis of the microcredit state of the art contrasted with the fieldwork done in Peru. A qualitative research methodology was used; 29 in-depth face-to-face interviews were done with different microfinance agents: MFIs, NPOs, microfinance associations, and microfinance customers in Peru. Peru has been chosen because it has a dynamic and well-regulated microfinance sector with more than 70 entities specialized in microfinance. Though statistical generalization is not possible, interview data provided rich and contextual evidence, which is often missing from a quantitative research approach. This paper highlights the importance of financial and accounting education in microcredit beneficiaries and how can it be enhanced in the digital age. The COVID-19 pandemic has forced vulnerable population to embrace new digital technologies and has highlighted the digital gap that still exists in Latin America although this situation presents opportunities and challenges.

This present study contributes to the debate over how to improve microcredit intervention\'s impact on the more vulnerable and identifies some unique insights into the interrelationships of financial education and financial inclusion. The results of the present study confirm that financial and accounting education are key elements in financial inclusion.

Keywords: Financial inclusion; Microfinance Institutions; Economic Development; Financial Education.

JEL classification: O16; G21; O15.

¡Cuidado con la brecha en la inclusión financiera! Trabajo de campo de las instituciones de microcrédito en Perú

RESUMEN

La inclusión financiera sigue siendo una cuestión política clave. Desde que el microcrédito captó por primera vez la atención del público, las instituciones de microfinanciación (IMF) se han expandido rápidamente por todo el mundo. Aunque gran parte de la literatura económica y financiera ha destacado la importancia de la microfinanciación como factor de desarrollo, también existe un intenso debate sobre su eficacia como herramienta de desarrollo. Este trabajo es un análisis descriptivo del estado del arte del microcrédito contrastado con el trabajo de campo realizado en Perú. Se utilizó una metodología de investigación cuali-tativa; 29 entrevistas en profundidad cara a cara con diferentes agentes de las microfinanzas: IMFs, ONLs, asociaciones de microfinanzas y clientes de microfinanzas en Perú. Se ha elegido Perú porque tiene un sector microfinanciero dinámico y bien regulado con más de 70 entidades especializadas en microfinanzas. Aunque la generalización estadística no es posible, los datos de las entrevistas proporcionaron una evidencia rica y contextual, que a menudo falta en un enfoque de investigación cuantitativa. Este trabajo destaca la importancia de la educación financiera y contable en los beneficiarios de microcréditos y cómo puede mejorarse en la era digital. La pandemia del COVID-19 ha obligado a la población vulnerable a adoptar las nuevas tecnologías digitales y ha puesto de manifiesto la brecha digital que aún existe en América Latina, pero esta situación presenta oportunidades y desafíos.

El presente estudio contribuye al debate sobre cómo mejorar el impacto de las intervenciones de microcrédito en los más vulnerables e identifica algunas ideas únicas sobre las interrelaciones de la educación financiera y la inclusión financiera. Los resultados del presente estudio confirman que la educación financiera y contable son elementos clave en la inclusión financiera.

Palabras clave: Inclusión financiera; Instituciones de microfinanciación; Desarrollo económico; Educación financiera.

Códigos JEL: O16; G21; O15.

1. Introduction

Global Poverty and financial exclusion provide the motivation for this research. Access to financial services is present in at least 5 of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set by the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Growth. Although in the past few years, the world has seen the most rapid progress towards SDG 1 (No Poverty), World Bank estimates that there are still more than 800 million people (9% per cent of the global population) that subsist on less than US$1.90 a day, of which 75 million are in Latin America. Most of these individuals are unbanked and relay on local informal economies. Based on this evolution, it was expected that this figure could decrease to 6% by 2030, however Covid-19 now threatens to increase extreme poverty in many countries (United Nations, 2019). The coronavirus has not only created a sanitary crisis but also a deep economic crisis. The current COVID-19 environment has created an unprecedented challenge for the continuity of microfinance institutions (MFIs), especially small and medium-sized ones, when their financial services are needed more than ever by small businesses. The economic and social effects of the pandemic have significantly impacted women’s autonomy and have highlighted the digital gender gap that still exists in Latin America.

In addition, Banerjee, Duflo & Kremer were awarded the 2019 Nobel Prize for their work fighting poverty. All three were recognized for their “experiment-based approach” to tackling global poverty and discovering which educational outcomes or child health initiatives do actually work. Financial inclusion has been broadly recognized critical in alleviating poverty and achieving inclusive economic growth. It is in this context that Muhammad Yunus developed the idea of microcredit in early 80s in Bangladesh and founded the Grameen Bank. This concept consisted in giving small loans to the bottom of the pyramid with the objective of improving their quality of life (Yunus, 2003). The primary purpose was to provide an alternative to the oppressive regime of traditional moneylenders, that was the only source of credit available to the more vulnerable population. One of the Grameen’s innovations was to create borrowing groups, mainly women, with the objective to empower and help them to sustain their home-based microenterprises. In the following decades, microfinance institutions (MFIs) started offering a wider range of financial products and services; payments and deposit facilities, savings accounts and insurance products. In addition, the microfinance industry undergone a tremendous development from NPOs (Non-Profit Organizations) to regulated financial entities, improving the level of efficiency and sustainability (Bibi et al., 2018; D'Espallier et al., 2017; Gutierrez-Goiria et al., 2017), but there is still a long way to go. The need for financial innovation to serve the poor through mobile banking is gaining attention.

Today Yunus’s vision is being questioned and the impact of microcredit on marginalized people remains debated. Although much economic and financial literature has highlighted the importance of microfinance as a factor in development, there is also an intense debate about its effectiveness as a development tool. Gutiérrez-Nieto & Serrano-Cinca (2019) argue that “Microfinance has proved robust as a banking idea but not as an anti-poverty intervention”. Feffer & Pollin (2007), also concluded “Making credit accessible to poor people is a laudable aim. But as a tool for fighting global poverty, microcredit should be judged by its effectiveness, not good intentions”. A variety of studies provide evidence that other factors are also very important to explain poverty reduction such as: quality of the institutions, monetary stability, sustained growth, job creation, foreign trade (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012; Rodrik et al., 2004); social policies based on conditional cash transfer (CCT) (Biderbost & Jiménez, 2016). In addition, donors and governments are demanding more evidence of the effectiveness of development aids experiences (Van Rooyen et al., 2012; Hermes & Lensink, 2011; Biderbost & Jiménez, 2016). Researchers are making great efforts to provide evidence of the impact of microfinance, but in general it is difficult in social sciences to provide robust evidence (Lacalle & Rico, 2007). Some researchers even suggest that microcredit can have a negative impact on the most vulnerable and suggest that employment, not microcredit is the solution (Blattman & Ralston, 2015; Bateman & Chang, 2009; Karnani, 2006, 2007) or that the impact is very limited (Cull et al., 2018; Prahalad & Hammond, 2002). Recent research suggests that the low impact of microcredits in the life of the poor can be among others partly due to the low level of financial education (De Mel et al., 2014; Karlan & Valdivia, 2011). Therefore, the microfinance model must be reviewed in order to identify the key factors that might help to increase the impact on the more vulnerable with a broader view. What really matters is identifying the conditions under which MFIs work best, what is the most adequate model, technology, and institutional environment for microfinance institutions and their clients.

Undeniably there is a close relationship between economic development and financial inclusion (Deb & Kubzansky, 2012). That is the reason why financial inclusion remains a key political issue and eradicating poverty in all its forms is one of the primary goals of the United Nations (UN) 2030 global agenda. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) main objective is to strengthen the rule of law and promote human rights. One of the objectives stated, “Access to finance by poor and vulnerable groups is an important tool for poverty reduction”. Such access can empower them by building their asset base, support income-generating activities and expand their range of choices. In this context, the purposes of this paper are to understand the effectiveness of microfinance institutions in alleviating poverty and to identify current challenges to improve impact on microcredit beneficiaries. However single solutions continue to be inadequate in confronting the prevalent problems of poverty (Leatherman et al., 2012).

This paper includes in the first part a bibliographic review and contextualisation of microfinance industry and financial inclusion. In the second part we cover the fieldwork done in Peru. This consisted of 29 semi-structured interviews and discussions done face to-face with different microfinance agents: MFIs, NPOs, microfinance associations and microfinances customers. The 29 interviewers have been carefully selected based on their specific roles allowing us to get a full picture of the microfinance market in Peru.

We chose Peru because it has a dynamic and well-regulated microfinance sector compared with other countries in Latin America. Currently, there are over 70 entities specialised in microfinance with outstanding loan portfolio of US$ 12.7 billion and more than 5 million borrowers (Microfinance Barometer 2018). Following the advice of BBVA Microfinance Foundation, that has MFIs all over Latin American countries, we selected three MFIs in Peru due to the differences in size and organizational models. We visited MiBanco, which is the largest MFIs in Perú and Financiera Confianza (FC), together they have more than 40% of market share. Representing the world of NPO we visited, ADRA an international organization focused on women savings groups. We examined their commercial models, target segments, services offered and their potential for archiving their mission of alleviating poverty. In addition, we selected the more active MFIs Associations and finally, to better understand the microfinance context, we also visited some microfinance customers in the area of Lima. Finally, we highlight our findings and define interesting recommendations and conclusions that emerged from our research study. This present study contributes to the debate over how to improve microcredit intervention impact on the more vulnerable and identifies some unique insights into the interrelationships of financial education and financial inclusion. We have included a section that covers the COVID-19 effects and challenges on MFI.

2. State of the art

2.1. Financial inclusion

Financial inclusion has substantial benefits for individuals and is critical for reducing poverty. It is also essential for inclusive economic growth. Several studies show that access to financial products ensures people are better able to start or expand new businesses, increase education and improve living standards (Armendariz & Morduch, 2010; Leatherman et al., 2012).

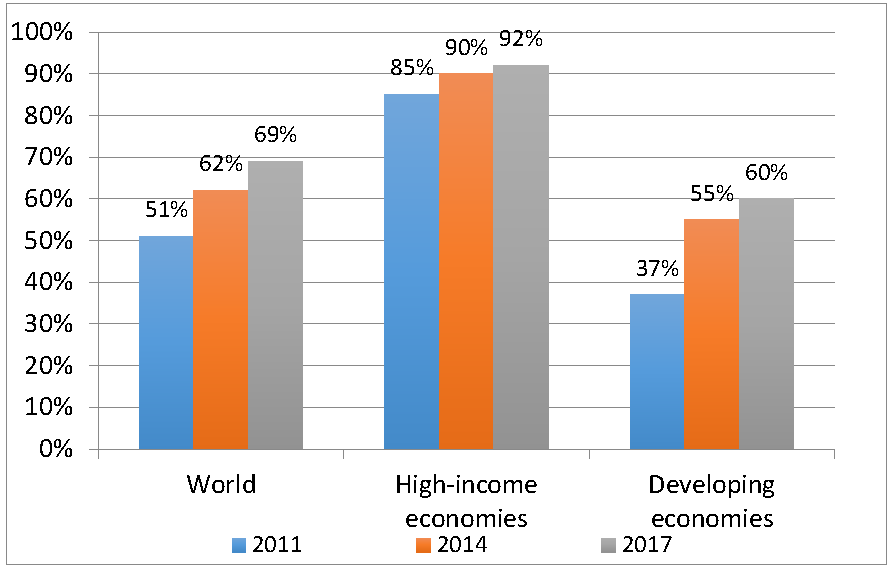

Access to financial services for both small entrepreneurs and individuals can lift them out of poverty and contribute to the community’s economic growth (Solo, 2008). Account ownership is one of the most common indicators for establishing the level of financial inclusion. In 2011, the World Bank (WB) launched a Global Findex database that covers more than 140 economies. The 2017 database has recently been published. Figure 1 demonstrates that real progress has been made in expanding financial inclusion: between 2011 and 2017 the number of people worldwide with a bank account grew by 1.2 billion. However, 1.7 billion adults (31 per cent of the global adult population) remain unbanked most of who are in developing economies (Worldwide Global Findex 2017).

Figure 1. Evolution of account ownership (2011-2017) Adults with an account (%)

Source: Authors' own compilation using Global Findex database 2017.

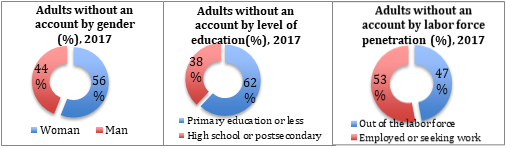

Not surprisingly the unbanked population in all the countries show similar characteristics: lower income and lower education than the population at large; they are young, 30 per cent of adults with no account are aged 15 to 24, 62 per cent have little or no education, and 47 per cent are unemployed. Additionally, most unbanked adults are women, as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Unbanked population ranked by level of education, gender and employment status

Source: Authors' own elaboration using Global Findex database 2017.

More people in Peru have gained access to financial services in recent years, with bank account ownership increased to 43 per cent in 2017 from 20 per cent in 2011. Both banks and non-banks increased their presence in rural areas and also helped the new channels such as mobile money and online platforms. Indeed, much of the progress can be attributed to the financial inclusion policies taken in place after the Maya Declaration, which set a target of 75 per cent account ownership by 2021 (AFI, 2015). Notwithstanding considerable progress, gaps remain. For example, the number of bank accounts in Peru is below the Latin America average of 54 per cent and below the world global average of 69 per cent. Gender gaps in account ownership remain with the difference between men and women not having an account of 17 per cent in 2017 (Global Findex 2017). In Peru a large poor population live in remote areas and the only way to access financial services is by using new technologies, such as digital payment or mobile money accounts. During the Pandemic, the Peruvian government has opened accounts using the National Identity Card (NID) numbers in Banco de la Nación with the purpose that every citizen will have a digital savings account. The accounts are being used for government payments, transfers and reimbursements, including those related to COVID-19 (El Peruano, 2021).

Another remarkable case is India, where adults with accounts increased to 80 per cent in 2017, thanks to the cooperation between government and private institutions. India’s biometric identity scheme, and government benefit programs paid through accounts had helped to increase financial inclusion (Raman, 2018). In the same period, in Africa 232 million accounts were added. For example, in Kenya, mobile financial services are offered by mobile network operators, and mobile money accounts do not need to be linked to an account at a financial institution, that has helped to increased account ownership to 72 per cent of adults in just a few years.

Other important results of the Global Findex 2017 are the most common reasons for not having an account. The principal one is the lack of money, 66 per cent of adults without an account identified this as the primary reason, and 20 per cent said it was the only reason. Other reasons include (in order of diminishing importance): no necessity for an account; accounts are too expensive; financial institutions are located too far way; lack of required documents; inability to get an account; lack of trust in financial institutions and religious reasons (Karlan et al., 2014). In addition, the rural poor use of their bank accounts is very limited due to financial illiteracy and other problems (Sen & De, 2018). Moving from cash-based to digital payments has many potential benefits for both senders and recipients (Ontiveros et al., 2014) for example the government benefit programs should be paid through accounts (Raman, 2018). The enormous growth of mobile banking has created a new opportunity to expand financial services to population living in remotes areas (Ammar & Ahmed, 2016). Mobile money accounts may help reduce the gap between developed and developing economies in terms of financial inclusion. The way to increase account ownership is to improve the level of financial education, to increase trust in financial institutions and to encourage the use of mobile banking reducing the level of cash payments. For example, payments should be digitalised, and private companies and the government should pay wages or CCF through accounts. Even in rural areas, unbanked adults have devices that allow them to make and receive payments. The most important challenges ahead are to reach those who are still excluded, to increase account use in a safe way by increasing digital and financial illiteracy of the new account's holders.

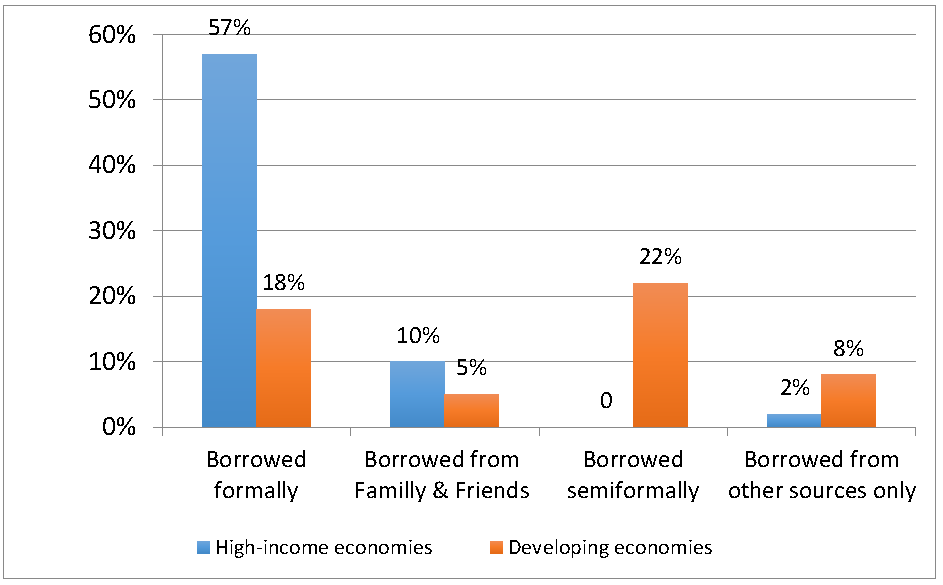

Regarding borrowing money, most borrowers in high-income economies rely on formal financial institutions, while in developing economies they tend to borrow money from family or friends and use other sources of informal lending (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Adults borrowing money in 2017 (%)

Source: Authors' own compilation using Global Findex database 2017.

2.2. The microfinance industry

Microfinance industry was born to fill the gap in financial inclusion of the most vulnerable population. Since Grameen Bank was created in 1983 Microfinance Institutions (MFIs) have expanded rapidly all around the world with the primary mission to alleviate poverty by giving small loans, primarily to female entrepreneurs (Yunus, 2003). Yunnus vision was that microcredit was an effective and commendable tool for reduction of poverty, because behind each microcredit was a potential entrepreneur. According to the Microfinance Barometer 2018, MFIs reached in 2017, 139 million low-income clients with a loan volume of US$114 billion. The following table displays microcredit activity by country.

Table 1. Top ten countries by number of borrowers and loan portfolio

| Number of beneficiaries (million) | Total credit (US$ billion) | |

|---|---|---|

| India | 50.9 | 17.1 |

| Vietnam | 7.4 | 7.9 |

| Bangladesh | 25.6 | 7.8 |

| Peru | 5.1 | 10.8 |

| Mexico | 6.8 | 4.4 |

| Colombia | 2.8 | 6.3 |

| Cambodia | 2.4 | 8.1 |

| Pakistan | 5.7 | 1.8 |

| Brazil | 3.5 | 2.6 |

| Philippines | 5.8 | 1.3 |

Source: Author’s own compilation, from Microfinances Barometer 2018.

Latin American countries comprise half the list in terms of volume of credit. Peru, with a total volume of US$10.8 billion, ranks first in Latin America and second after India. India and Bangladesh are top the list in terms of the number of beneficiaries.

Nevertheless, the number of poor entrepreneurs who access microcredits remains low (Ammar & Ahmed, 2016; Bateman & Chang, 2009; Banerjee & Duflo, 2007; Simanowitz & Walther, 2002). There is still a large population who are financially excluded for several reasons: they may not have access to MFIs, or are not creditworthy (Hulme & Mosley, 1996); they are excluded from group-lending projects by other group members or the requirements for granting the loan cannot be met, or the minimum amounts are too high (Kirkpatrick & Maimbo, 2002; Mosley, 2001). Also, many creditworthy micro-entrepreneurs have no interest in microcredit financing because they fear the sanctions for non-payment. These people are the most risk-averse, and they do not understand the concept of borrowing nor do they have a savings culture (Urquía-Grande & del Campo, 2017; Urquía-Grande & Rubio, 2015; Adusei, 2013; Van Rooyen et al., 2012; Ashraf et al., 2006; Duflo et al., 2006; Thaler & Benartzi, 2004).

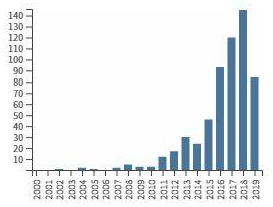

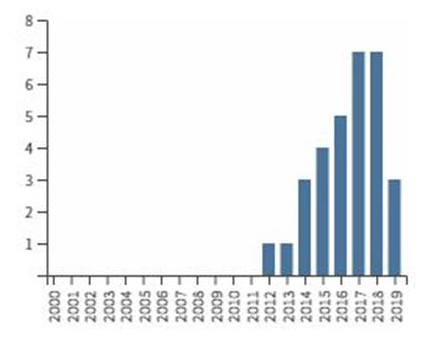

In the past few years, there has been an increase in joined research regarding financial inclusion and microfinance, as demonstrated by the number of articles found in the Web of Science (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Research in financial inclusion and microfinance (number of publications per year)

Source: Authors' own compilation using Web of Science data.

Gutierrez-Nieto & Serrano-Cinca (2019) reviewed 1,874 papers published from 1997 to 2017 to perform a scientometric analysis of the microfinance field. The study identified, the evolution of the trend topics in microfinance research: the most recent ones are financial inclusion, social entrepreneurship and Islamic microfinance. The classic topics remain, such as mission drift, as well as long-standing ones such as efficiency, outreach and sustainability.

Nevertheless, in recent years the efficiency, scope and effectiveness of microfinance have been questioned (Hermes & Hudon, 2018; Hudon et al., 2019, 2020, Gutierrez-Goiria et al., 2017; Mader, 2018; Banerjee et al., 2015; Daley-Harris, 2009; Ditcher, 2007; Cohen, 2003). Theory and evidence have revealed concerns about the real impact of microcredits on the alleviation or reduction of poverty (Cull et al., 2018). There are concerns that the microcredit market may be saturated and that intense competition between MFIs is pushing customers into over-indebtedness (Risal, 2018; Angelucci et al., 2015; Schicks, 2013, 2014). Some microcredits research experts point out the risks of high interest rates, high transaction costs and the risk of over-indebtedness (Hermes & Hudon, 2018; Cull & Morduch, 2018; Morduch, 2017, 2016; Roodman & Morduch, 2014; Angelucci et al., 2015; Hudon & Ashta, 2013; Hudon & Sandberg, 2013; Kappel et al., 2010). Smart campaign 2016 publication on Peruvian consumers reported that the average rural household spends 35 per cent of their monthly income on debt repayment and that 16% are late on their payments. On the other hand, supporters of microcredit argue that it helps to improve qualitative factors such as the empowerment of women (Sabharwal, 2002), access to education, and an improvement of other social aspects that transcends the immediate surroundings of the lenders (Simanowitz & Walther, 2002).

In addition, a new generation of more rigorous impact research studies using randomised control trials (RCT) have found no evidence that microcredits increase household income, but only that microfinance is helping the beneficiaries to deal with their circumstances (Banerjee et al., 2015; Tarozzi et al., 2015; Crèpon et al., 2011). The literature review of Cull et al. (2018) shows only modest average impacts on microcredits customers or zero impact on the poverty of clients (Roodman, 2012). In addition, Duvendack et al. (2011) performed a meta-study, revising 74 papers, and found that almost all of them used weak methodologies, inadequate data or lack of rigor. Given that donors and government want to ensure the social return of development aids, the investment in impact assessment in development programmes is no longer a marginal issue and has become a strategy. Financial inclusion is a complex field and unrealistic expectations will lead to misaligned priorities and disappointments. Decision-makers should check their positions on financial inclusion, if only to clarify better what benefits they expect it to bring to whom, and why (Mader, 2018).

In the case of microfinance, donors must judge whether providing the poor with access to financial services yields a sufficient social return compared to alternative poverty alleviation efforts. Between 2013 and 2016, investment in impact assessments of development aid programmes grew by 385 per cent: in 2016, it was US$22.1 billion (Global Impact Investing Network (GIN), 2018).

All these researches have allowed us to look at the problem from different angles. It is time to focus on the Microfinance Institutions challenges for the next decade, among others: how to increase social impact through financial education using mobile banking and Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs).

As the COVID-19 pandemic drags on, there is a growing concern about the impact on microfinance institutions (MFIs) and their clients. Many Latin-American governments responded quickly with recommendations for freezing interest, delaying loans repayments and economic subsidies for low-income population mainly provided via digital channels. The ability of borrowers to repay loans will determine the MFI's ability to survive the pandemic.

2.3. Financial Education

Recent research shows that financial education is a key element for increasing financial inclusion. For example, authors such as De Mel et al. (2014), Bali & Varghese (2013), Verrest (2013), Berge et al. (2012), Karlan & Valdivia (2011), McIntosh et al. (2011) and Gubhert & Roubaud (2005), have studied the impact of different microfinance programs implemented with compulsory training in business and conclude that financial education improves financial outcomes. Even in developed economies, the level of financial literacy has a major impact on financial stability. The strong links between financial and accounting literacy and the levels of success in managing microcredits have attracted considerable attention from researchers in the field of cooperation programs. However, research on this issue remains scarce, as demonstrated by the number of articles written about financial inclusion, microfinance and financial education found on the Web of Science (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Research in Financial Inclusion, Microfinances and financial education (number of publications per year)

Source: Authors' own compilation from Web of Science data.

Most researchers agree that the impact of training programmes improves when tuition is adapted to the needs of micro-entrepreneurs. Bali & Varghese (2013) examined several variables to discover which of them had the greatest influence on training success. Infrastructure variables such as the distance to the village and communication problems are crucial. Other variables such as whether the training was voluntary or if it was linked to a credit were also very important. Authors as De Mel et al. (2014), have also conducted an RCT that analysed the impact of business-training courses in conjunction with different types of financial lending. There was no significant impact on women who already had a business, while training proved more effective on women starting up businesses. The lack of financial skills is one of the main problems for micro-entrepreneurs when managing a micro-business. Basic accounting is essential, as it provides information on which to base decisions, and to plan, forecast and control (López-Sánchez et al., 2020; Fernandes et al., 2014; Tang & LaChance, 2012).

For over a decade, Freedom from Hunger (FFH) in cooperation with different MFIs all around the world have offered an integrated financial and education product, called Credit with Education for population in the bottom of the pyramided. Credit with Education services focus on group lending for women because of their economic and domestic roles within the household. Credit with Education provides participants with small loans, and education in business management and other topics such as health and nutrition. Evidence from Credit with Education programs indicates that many of the desired impacts have been achieved. Field agents gave the training in sessions of 20 to 30 minute during the regular Credit Association meetings. Field agents are usually from the local area with some school education. Their role is to be a facilitator, not a teacher. This methodology is very interesting but is not scalable given that customers live in remote rural areas and field agents must cover long distances with poor infrastructure. The main training contents are health, food and basic business skills. Business education introduces women to the concepts of “profit and loss,” “adding value,” “managing money,” “selling strategies,” “market evaluation,” “inventory management” (Fiala, 2018). Vor der Bruegge et al. (1999) have done a cost analysis of three years of four different Credit with Education programs to estimate the cost of education in addition to the cost of village banking. They come out to the figure that the cost of education is between a 6 per cent and 10 per cent of the total cost of the programme. For example, the annual cost per client served in Bolivia was $63.82. The cost analysis suggests that eliminating the “extra education” could only save $3.51 per client per annum.

In the same line, Microfinance-Plus programs are becoming more popular among MFI’s. They also offer non-financial services (training in business, technical and social skills) in addition to financial services (credit, savings, insurance, transfer and payments). In this line, Garcia & Lensink (2019) analysed a sample of 478 MFIs in 77 countries. Twenty-five per cent of the MFIs offer business services together with microcredit to improve managerial process (accounting, finance, marketing, etc). The problem is that micro entrepreneurs in developing countries rarely use management skills as accounting or inventory control (McKenzie & Woodruff, 2014).

In other to evaluate the impact of financial education, authors such as Kalra et al. (2015) have developed a Microfinances Clients Awareness Index (MCAI) based in two pillars: Awareness and Skills. Awareness cover: loan basics and insurance basics, Skills sub-pillar include basic computing skills, financial skills and comparing products. All together there are 13 indicators. The MCAI could be useful to compare different MFI and could permit country rankings. It can also serve as a tool to drive governmental policies.

Therefore, financial education must be identified as a priority by the government and the different institutions involved. But raising financial education levels among the most vulnerable population is not easy, could be very expensive and takes time. Coordination and long-term planning among the different actors are needed.

2.4. Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs)

We are currently in a profound digital revolution, characterised by unstoppable technological advances (Ochoa et al., 2016). This digital revolution, that comprises mobile communications and new ICT solutions, also affects microfinance industry. Mobile phones, and more concrete smartphones, have increased exponentially in recent years, mainly due to the global investment on mobile network and the design of low-price devices. Seven out of ten homes belonging to the poorest 20 per cent of the population have a mobile phone (Perlman, 2017). Access to basic infrastructure and broadband connection has also been growing rapidly. GSMA (2019) estimates that more than 82 per cent of adults in high-income economies have access to the Internet but only 40 per cent in developing countries. This percentage goes down to 28 per cent for the poorest 40 per cent of the population.

SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure) is the goal that reveals the largest gap between developed and developing countries. This highlights the need to accelerate investments in technology and innovation globally and to boost capacities and skills.

Pérez-Estébanez et al. (2017) found that micro entrepreneurial total assets are connected with management accounting with ICT, ICT education level and ICT adoption.

McKinsey & Company (2016) confirms that Banks, telecoms companies, and other providers are already using mobile phones to offer basic financial services to customers. “Mobil Banking” will provide the unbanked with a wider and appropriate set of digital financial products and services that will help to accelerate social development without the need for major investment or additional infrastructure.

For example, “Mobile money” allow people to make payments using their mobile phones, even with simple text-based phones and without having a traditional bank account. Moving from cash-based to digital payments has many potential benefits, for both senders and receivers. It can improve the efficiency of making payments by increasing the speed of payments and by lowering the cost of disbursing and receiving them.

Ontiveros et al. (2014) affirm that new technologies can improve financial inclusion with less expensive financial services models. The poorest in rural areas will benefit from more accessible and efficient financial services, such as branch-less banking models, mobiles payments and e-training methods, more dynamic, innovative and cost effective.

2.5. The COVID-19 and MFI

The COVID 19 Pandemic was first reported in December 19 and in March 20 the World Health Organization (WHO, 2020) declared a global pandemic. The coronavirus has not only created a sanitary crisis but also a deep economic crisis. In other to reduce the virus transmission, most countries imposed strict lockdowns. The mobility restrictions are affecting every company and person all around the world but more deeply the most vulnerable population. Covid-19 now threatens to increase extreme poverty in many countries (United Nations, 2019).

The pandemic knocked Latin America and the Caribbean very severely because of the region's structural vulnerabilities (e.g., more people working in informal markets and in sectors that require physical proximity, as tourism, insufficient health care systems and finally unequal access to digital tools. International Monetary Fund (IMF), estimated a 7,4% decrease of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the region. The social and human costs of the pandemic have been enormous. It is estimated that more than 18 million people have been infected, and about 17 million people have fallen into poverty. Peru is the worst country in the region with a 12% decrease in GDP (IMF Blog, 2021).

Employment remains below pre-crisis levels reaching an unemployment rate of 10,4% per cent in 2020. Inequality has also increased in most countries; the unemployment rate for women is estimated to reach 22.2% in 2020. The economic and social effects of the pandemic have significantly impacted women's autonomy. The female labour force participation rate in Latin America and the Caribbean fell by 6 percentage points in 2020, losing 10 years of progress (CEPAL, 2020b). More than 55% of women in the region work in the sectors most affected by the COVID-19 crisis, including accommodation and food service activities sector (associated with tourism). In Peru it is estimated that 76,4% of these jobs were held by women in 2019

Despite this situation, FMI is estimating a regional GDP growth forecast for 2021 of 4.1 per cent due to better-than-expected vaccination campaigns, growth prospects for the United States, and higher prices for some commodities. (FMI, 2021)

During the last few months the lockdowns have forced vulnerable population to embrace new digital technologies but this new situation presents opportunities and challenges. For example, part of the low-income population did not have or did not use banks accounts. World Bank, (2020) estimated that during 2018, 81% of retail purchased in Latin American was conducted with cash. Even if they have a bank account they withdraw the money as soon as their wages or subsidies are paid into the account. This situation is changing and Mastercard has reported that approximately 40 million people across Latin American have become banked over the past few months (MasterCard, 2020). The Governments subsidies and CCT has been critical in reducing the use of cash and encouraging the opening of new bank accounts and therefore increasing financial inclusion. Some of the programs that have been implemented recently in Latin America are:

Peru has just launched a National Identity Card Account. The government will open accounts using the National Identity Card (NID) numbers. The purpose of this new law is that every citizen will have a digital savings account at Banco de la Nación, in line with the objectives and guidelines of the National Financial Inclusion Policy. The accounts are being used for government payments, transfers and reimbursements, including those related to COVID-19 (El Peruano, 2021).

In Mexico, migrants in the United States will be able to open bank accounts remotely at Banco del Bienestar, while their families in Mexico will be able to open their own accounts and withdraw money in pesos. This new policy aims to attract both migrants and remittance recipients to the banking system and facilitate remittance transfers, which are the livelihood for many low-income households in the country.

New payment models are expanding throughout Latin America. Transactions are carried out with the help of resources such as the QR code, which can be used, for example, to identify the payer. Brazil, Mexico and Peru have recently moved forward with multi-bank payment projects. For example:

In Brazil, the instant payment system, PIX, will allow to send and receive amounts in real time from a variety of media, including mobile applications. When a payment or transfer is made, the money will immediately go to the recipient's account. The government has been using PIX to transfers subsidies related to COVID-19 causing a decreased a 73% the number of people with no bank account (CEPAL, 2020b).

Mexico's CoDi went live in early 2019. CoDi® is a platform developed by Banco de México to facilitate payment and collection transactions through electronic transfers, through cell phones. CoDi® uses QR code and NFC technology to facilitate cashless transactions for both merchants and users (Banco de Mexico, 2021).

In Argentina, despite the digital wave driven by the COVID-19 pandemic, there is still a strong preference for cash. Mercado Libre, the region's largest e-commerce platform, are offering in-store cash withdrawal services through its Mercado Pago digital wallet and QR code.

The current COVID-19 environment has created an unprecedented challenge for microfinance institutions (MFIs), especially small and medium-sized ones, at a moment when their financial services are needed more than ever by small businesses. In response to the pandemic most MFIs around the world have try to help their customers to cope with the new situation, easing loan conditions, postponing repayments, implementing a moratorium or loan restructuring to clients who request it. The ability of borrowers to repay loans will determine the MFI's ability to survive the pandemic. Other aspect is the reduction of lending levels. It can be caused by the reduction of client demand, increasing client risk or MFI reducing the levels of risk tolerance. This raises concerns about the impact on low-income clients who depend on microfinance for their livelihoods. For the moment, this flexibility allows MFIs to avoid worse outcomes as they try to adapt and work through the crisis. However, it raises a question: How long will these measures be sufficient?

The Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP) conducted a Global Pulse Survey of Microfinance Institutions during September to December 2020 (CGAP, 2021) with the purpose to identify the challenges that MFI are facing. More than 399 microfinance institutions participated in at least one part of the survey. The survey highlighted the risk of deterioration of loan portfolios and MFI liquidity levels. CGAP's global survey data show strong increases in the number of nonperforming and restructured loans, but also strong capitalization that mitigates the risk of insolvency in most MFIs.

Portfolio at risk greater than 30 days (CeR>30) i.e., loans more than 30 days past due has increased a 41%, compared to a pre-pandemic baseline of June 2019. The survey also noticed that the size of the MFI matters; small MFIs show levels of CeR>30 almost twice as high as larger institutions. If restructured loans are added to the level of CeR>30, the "distressed portfolio" by the end of May 2020 reached almost 50% among our respondents.

Declining portfolio quality is not the only risk that threatens the solvency of MFIs. If there is a decline in loan demand or lenders' risk appetite eventually reduces portfolios, MFIs may not be able to generate sufficient income to cover expenses.

Finally, due to the lockdown most MFIs employees work from home or have reduced working hours forcing MFIs expanding the use of remote channels to reach clients. About one-third of MFIs participating in the survey have increased their call center operations or their digital channels. The pandemic has highlighted the digital gap that still exists in Latin America. Bearing all these in context, we define the following research question:

RQ1: What do Microfinance actors claim are the key factors for improving financial inclusion?

3. Methodology and context

3.1. Methodology

Our research methodology followed qualitative, descriptive and interpretative case research (Vaivio & Sirén, 2010; Lacalle & Rico, 2007). The research is based on data analysis, a review of the literature and semi-structured interviews and discussions with key microfinance actors in Peru. We selected Peru for our fieldwork because it has a dynamic and well-regulated microfinance sector. The fieldwork done in Peru consisted of 29 semi-structured interviews and discussions done face to-face with different microfinance agents: MFIs, NPOs, microfinance associations and microfinances customers. We analysed three MFIs, that were selected due to the differences in size and organizational models. Finally, to better understand the country context, we also visited some microfinance customers in the area of Lima. The summary of these interviews is in section 4. Several types of data have been used. We have gathered information directly from the interviewees and observation in an exploratory and inductive manner (Rautiainen et al., 2017; Taylor & Bogdan, 1984). To offset any subjectivity and support our analysis, we analysed multiple recent reports and research studies such as Global Microscope on Financial Inclusion 2018, Microfinance Barometer, 2018, Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2019 and Global Findex 2017. Though statistical generalizability is not possible, in-depth interview data provided rich and contextual evidence which is often missing from a quantitative research approach (Yong, 2019). Differences in training practices at MFIs may reveal differences in the underlying financial inclusion and impact of microfinance. The possible interviewees bias is reduced after two hours of face to face interviews with the researcher.

Furthermore, our analysis is based on understanding the behaviour of organisational actors, which was gained by observations during the interviews and through discussions, meetings, emails, phone calls and qualitative analysis of follow-up interviews about training and microfinance. We focused on four areas: financial inclusion; financial education; selection and monitoring of beneficiaries and strategies for addressing technological innovations.

3.2. Peru context

We chose Peru because it has a dynamic and well-regulated microfinance sector. The microfinance industry in Peru has contributed to the development of the Peruvian economy and benefited the general population. Over the past decade, Peru has been one of the fastest-growing economies in South America, with an average annual GDP growth rate of 5.9 per cent (World Bank). Currently, there are over 70 entities specialised in microfinance. At the end 2017 Peru has an outstanding loan portfolio of US$ 12.7 billion and more than 5 million borrowers (Table 1). It ranks first in Latin America and second after India worldwide (Microfinance Barometer 2018). In relation to Government and Policy Support for Financial Inclusion, Colombia and Peru hold the top two spots in the overall rankings of the 2018 Global Microscope on Financial Inclusion. This index analysed the working environment for microfinance, the regulatory system, the competitive and innovative market, and client protection. Much of Peru’s success in microfinance can be attributed to prudent regulation, strict supervision, balanced with limited government intervention (Chen, 2017). The Peruvian economy, the seventh largest in Latin America, has experienced a structural change in the past three decades. Currently, the services sector is the main contributor to the country’s GDP driven by telecommunications and financial services, which together account for nearly 40 per cent of GDP. In addition, Peru ranks on the top countries in terms of entrepreneurship (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2019). However, the country still has a long way to go towards modernisation and competitiveness. In addition, competition has increased significantly in recent years, pushing MFIs to improve efficiency and sustainability. Although the rate of non-performing loans and write-offs has decreased there is still a 10 per cent of non-performing loans.

The use of cash is extensive throughout the region, owing to the high level of informal business in Peru. Half of the population receive their wages in cash and, in terms of transactions, 96 per cent pay for services and invoices with cash. In addition, people with an account do not use it frequently: only 17 per cent make regular transactions throughout the month, while this percentage rises to 65 per cent in more developed countries. Peru accounts for one of the most successful collaborative initiatives between financial institutions, government and telecommunication companies, the design and construction of a shared infrastructure for mobile payments. BIM is a digital app for making payments via mobile phones that aims to reach the unbanked in remote areas.

Microfinance institutions are present at the national level, with a growing number of new agencies, correspondent’s agents and the ‘shared window’ network run by the Banco de la Nación. These new initiatives have allowed MFIs to reach people living in rural and remote areas who were previously excluded from financial services.

At the end of 2018, total loan proceeds reached 45.308 million soles, representing an increase of 8,7 per cent from the previous year. The non-performing loans were 5,83 per cent. Microcredits to small businesses and micro-enterprise comprised 42.88 per cent of the total loan proceeds. In terms of customers, MFIs provided 36,27 per cent of credit to small businesses followed by Cajas Municipales with 34,56 per cent and MiBanco with 19,68 per cent (ASOMIF, 2019).

4. Case-study fieldwork research

4.1. Microfinance institutions

We visited three MFI in Peru: MiBanco, which is the largest MFI in Peru; Financiera Confianza (FC), and ADRA. Three microfinance associations were also interviewed and finally, five NPOs working in the sector of microfinances (See Annex 1 for the technical sheet of interviewers). Our findings are analysed and discussed in this section. Finally, recommendations for the future are defined.

4.1.1. MiBanco

MiBanco, with a 25 per cent market share, is one of the leading microfinance institutions in Peru. It is the result of the merger of Financiera Edyficar and MiBanco in 2014 and its mission is to transform the lives of customers through financial inclusion, thus contributing to the economic growth of Peru.

MiBanco has more than 714,400 customers, who are mainly micro and small entrepreneurs. It is the largest institution offering loans in the 0-150 thousand soles range, with a market share of 26.07 per cent in this segment. It has the biggest branch network in Peru, with 328 branches across the country and 5,713 credit officers. It also accounts for the largest network of collaborators (10,130) in Peru.

They informed us that, in order to increase the impact of microcredits, they also offer a wide range of non-financial services, including financial education. Some examples of recent initiatives in this area are; First, the university exchange programme MiConsultor, which provides consultancy services for micro-entrepreneurs; virtual education through the ‘Campus Virtual Romero’. Second, financial education workshops developed jointly with the German Foundation focused on improving the use of cash and budgeting process of credit beneficiaries. Third, a program developed together with the Inter-American Development Bank’s Multilateral Investment Fund (MIF) that will make a US$3 million grant to a project that will provide training to more than 100,000 women microentrepreneurs and small business owners in Peru. Half of Peru's GDP is generated by small and microenterprises, and women head over 40 percent of these companies. Investing in these women makes good business sense for the Peruvian economy and for the microfinance industry (Interviewee 1).

We are also worried by the increase of competition that is causing high customer rotation and over indebtedness. Banking agents, who have direct contact with the customers, are key figures in MiBanco and training programmes focused on retention of these agents, are also being developed (Interviewee 1).

4.1.2 Financiera Confianza (FC)

Financiera Confianza (FC), that belongs to “Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria Microfinanzas Fundation” (BBVAMF) , is one of the leading microfinance entities in Peru. It has 149 branches across the whole of Peru and serves around half a million customers. FC provides a wide range of financial products and services, including financial education. They primarily focus on women and young people under 30, which are the populations with the highest poverty rates.

BBVAMF has developed a new methodology called Productive Finance that allows loan officers to reach the entrepreneurs with all the information; it is like carrying the branch office in a mobile device. They share a cloud technology solution, a banking hub with multi-device mobile that allows them to provide online services, document digitalization and collect data. The platform helps them to do the follow up and measure impact assessment (Interviewees 2 and 3).

During the interviews they shared with us their customer profile and strategy.

The characteristics of our customer base are: 60 per cent are women, 45 per cent have primary education, 32 per cent live in rural areas and only 19 per cent are under 30 years old. We focus on women because they are more vulnerable, are considered better administrators than men and are more concerned about their families. We believe that supporting women means supporting the following generations. Although women account for 60 per cent of the group’s customers, they only represent 54 per cent of the total credit amount (Interviewee 4).

They also described the important role and challenges of the frontline officers.

Frontline officers or banking agents are key figures in MFIs, because they have direct contact with the customers. They have variety of functions: identify and provide information to potential customers, develop together with the customer the loan applications, and provide financial education to customers. Financiera Confianza (FC) focused its efforts in 2017 on retention and training programmes for banking agents. One of these programs was developed by Food for Hunger (FFH). It was an integrated education program within the MFIs to improve skills to frontline officers in several regions. The courses cover consumer protection, group facilitation techniques for delivering non-formal education and microcredit product management on line. In addition, to improve the capacities of supervisors and branch offices coordinators, the Foundation has developed a “School for Managers” program certified by ESAN University, in Peru that teach part of the content and validate skills in risk management, personnel management, sustainability, commercial strategy, client experience and new technology trends (Interviewee 5).

They highlighted the importance of financial education. FMBBVA believe that education is the only mechanism that can help improve micro-finances impact and reduce vulnerability; therefore, they have developed different education programmes. Some examples of lending with training programmes are shown below:

’Palabra de Mujer programme’ is a group-lending product designed for vulnerable women, includes financial training given at each monthly payment meeting. These trainings are run by branch managers and banking officials trained in conducting financial education (Interviewee 5).

’Ahorro para todos programme’ (APT) is a group-saving product with a financial education component, which is also designed for women in rural areas who want to improve their standard of living. Since launched, APT has gained more than 2,850 clients and trained more than 13,700 people in financial issues. The education programme uses puppets and theatre games to teach savings culture through gamification, and are also held in Quechua, which is the women’s native language (Interviewee 5).

’Echemos Números programme’ operated by Bancamía (Colombia). This programme provides the necessary skills for better money-management and to make better financial decisions. The programme includes financial assessment and/or face-to-face workshops given by the field agents (Interviewee 6).

One of the issues that arose in the interviews was the long process to assess the credit rating of customers given that they do not have any accounting records and work in the informal economy.

Front-line officers work with customers trying to produce pro-forma financial statements and complete the credit application form (Interviewee 5).

Finally, they are also concerned about the low customer retention rate that most MFIs are facing, which has been partially caused by increasing competition and lack of financial education.

This is a common problem for MFIs. The retention rate of micro-entrepreneurs is very low. It has been proven that in order to increase the microcredit impact customers should stay with the institution longer periods. Clients, who were poor when they joined Financiera Confianza, crossed the poverty threshold after two years of working with the institution (Interviewee 4).

4.1.3. Microfinance Customers. San Juan Próceres FC Branch, Lima, Perú

We visited three customers of Financiera Confianza (FC) in their premises and followed a semi-structured interview, see Annex 2. They all have a long relationship with FC and agree that the financial education provided with the credit by FC has been a key element in management their finance and their business.

Customer 1. Motor Bike Taxi

We have a long relationship with FC and agree that thanks to the support and credits provided by FC we have been able to make our business grow in a sustainable way (Interviewee 7).

Customer 2. Retail Shop and taylor made clothes

We appreciate mostly the support given by the credit officers, helping us to make the credit application and provided business and financial training (Interviewee 8).

Customer 3. Shoe repair Shop

Regarding accounting, the formal accounting is done by an external firm, but we keep control of records by hand. We agreed that an accounting app could be helpful, but we are afraid to lose control of our information (Interviewee 9).

4.1.4. ADRA Peru

The third institution we visited was the Adventist Development and Relief Agency (ADRA). This is one of the largest non-governmental aid organisations in the world, with a presence in more than 120 countries. It has worked in Peru since 1965 and focuses on projects that benefit people in poverty.

Our microfinance project uses community-banking methodology that focuses on female entrepreneurs. This model combines communal loans with education. The educational component focuses on all areas of client development, including the family, the community and business. Currently ADRA has more than 17,000 female customers, of whom 12 per cent live in rural areas and the rest in peri-rural areas (Interviewee 10).

4.1.5. Banco de la Nación, Perú

Banco de la Nación is a stated own bank with the largest branch network in Peru with the mission to provide financial services to citizens even living in rural remote areas and to promote financial inclusion through modern technology and self-sustaining management.

Within of the state's social inclusion policy, the bank plays an important role in vulnerable populations. Thanks to its important infrastructure with multiple channels throughout the national level. Most MFI’s used this wide network to reach their customers. In addition “the share window network” plays an important role in money transfers granted by the government in relation to Social Programs (CCT): Pension 65 and Contigo (Interviewee 11).

4.2. Microfinance associations

4.2.1 CEFI-ASBANK

CEFI is a non-profit educational organisation, belonging to ASBANC, the Peruvian Banking association. It provides financial education, specialisation, research and other services that enhance financial skills. It also promotes government specialisation and modernisation in areas that can impact financial inclusion and competitiveness of the country.

CEFI collaborate in designing and providing different education programs depending of the level of poverty, location, gender and special situations but is difficult to value the level of the financial skills acquired (Interviewee 12). Some examples of these programs are:

1- “CUNA más” is a program developed by the Ministry of Development and Social inclusion (MIDIS) whose objective is to improve the health of children under 3-year-old in extremely poor areas. They gave information regarding, health, nutrition, early learning skills.

2- “Programa Juntos” is one of the most important Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) government program launched in Peru in 2005. The program was targeted to the most vulnerable population in rural areas. The condition to get the CCT was that parents of children of less than five years must take their children to regular health checks. The training was done in schools, social places or private houses and the objective was to get a minimum education to be able to set up a business and graduate from CCT programs. The problem is that there is not enough professors. Recently in 2017 CEFI developed a training programme targeted to graduates of the CCT "Programa Juntos" focused on basic accounting, and cash-flow managment. The first experiment took place in Piura, Peru in collaboration with the University of Piura and the results were very challenging. They considered that most of the people that attended the training program was prepared to set up their own business and apply for a micro-loan (Interviewees 12 and 13).

They also provided us financial education training material: “Aprendiendo a cuadrar cuentas”, “Finanzas en mi colegio”, “Historietas de Educación financiera” & “Plan de Negocio”. All these materials covered the following issues: Differentiate family and business accounts, how to use a saving account, improving trust in financial institutions, basic accounting (recording transactions, cash-flows and budgeting process) and selling and marketing.

4.2.2 COPEME

COPEME, founded in Peru in 1991, is a decentralised network of NGOs that aims to strengthen micro and small enterprises through business development services and inclusive microfinance. Institutions associated with COPEME are NPOs located across the country and are dynamic agents in their local economies. COPEME channels international cooperation development projects.

COPEME’s long experience in public policy allows them to suggest best practice intervention models but they are not happy with the achievements in financial inclusion although there is a National plan where most players are involved. Financial education and MFI Institutional sustainability are the main pillars of the National plan (Interviewee 14).

Over the past few years, COPEME has run cooperative projects for managing risks in small and medium-sized MFIs and for developing technologies for financial inclusion (TEC-IN). The purpose of this programme is to increase financial inclusion using mobile phones and computer technology. These programmes aim to lower the costs of access to financial services in the rural population through mobile devices, including phones and computer systems. The project incorporates databases from COPEME’s strategic partner EQUIFAX regarding non-conventional customers, including records to credit providers and services in rural areas. This makes it easier to make risk assessments of potential customers (Interviewees 14 and 15).

4.2.3. ASOMIF

ASOMIF Peru is the national association of regulated non-bank financial institutions and has been a key figure in the definition and implementation of e-money in the Peruvian microfinance sector. ASOMIF’s member organisations serve over 3.5 million clients with a loan portfolio of over US$10.3 billion. ASOMIF also assists its members with client education initiatives. Its mission is to help their associates achieve sustainable growth, represent them in national and international institutions and provide members with a portfolio of services.

One of the most successful collaborative initiatives between financial institutions, government and telecommunication companies has been the construction of a shared infrastructure for mobile payments. The design and implementation of the BIM project ’billetera móvil’ aims to reach the unbanked in remote areas. BIM is a digital app for making payments via mobile phones. Although moving from cash to digital payments is difficult in developing countries it must be promoted because of the potential benefits for both senders and recipients. In addition, it can improve efficiency and security of the transactions. The platform also aims to promote savings.

Other initiatives of the Peruvian Government's superintendent of Banking, Insurance and Pension Funds (SBS) to prevent over-indebtedness is an online tool that allows users to monitor the status of their debts. This includes five-year of credit information: rating, total debt, interest paid from different institutions. Although the tool is freely available only a 10% of borrowers in 2017 checked their information (Interviewee 16).

4.3. Other Non-profit Organisations (NPOs)

4.3.1. BBVA Microfinance Foundation (BBVAMF)

BBVA Microfinance Foundation (FMBBVA), is a non-profit entity belonging to the Spanish bank “Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria, S.A”. (BBVA). BBVAMF operates in five countries in Latin America, though six MFIs. In 2018 the group signed off USD 1.44 billion in credits to 2 million vulnerable entrepreneurs. It is the biggest philanthropic organization in the region (BBVAMF, 2019).

The purpose of the Foundation is “to promote sustainable and inclusive economic and social development for disadvantaged people through Responsible Productive Finance”. We have been awarded for our contribution to [SDG5 “Gender Equality”] during the “SDG Awards”, for designing a specific and innovative strategy for the 1.2 million women in Latin America (Interviewee 17).

Another of the Foundation’s initiatives is to promote good corporate governance and we have designed Code of Corporate good practices. This Code provides a set of standards and principles for board members and management of MFI’s with are fundamental to translate principles of good corporate governance into practical action (Interviewee 17).

The Foundation has developed a cloud technology solution with multi-device mobile system that allows us to collect data in order to generate social impact indicators and realize impact assessment. Every year we publish the “Social Performance Report 2018” with complete information of the actions and results of the six institutions belong to the group (BBVAMF, 2019) (Interviewees 18 and 19).

4.3.2. CODESPA

CODESPA is a Development NPO with more than 30 years of experience. Formed by a group of professionals and experts in different disciplines committed to the development of all areas of life (economic, social and human) of the poorest people.

In Peru, CODESPA is mainly working with the tourism sector helping art-craft entrepreneurs in extremely poor areas to understand their business and their value proposition. They were also involved in an entrepreneurship project consisted in a $1.000 grant together with education. The training was done by CEFI using a new gamming methodology, it was given was individually and covered the development of business plans. More than 1.200 people attended, and the experience was very promising given than in a few years a high percentage becomes a medium size company (Interviewee 20).

One of the projects they were running in Guatemala in 2017 was “ENTRE TODOS”. Groups of people that save and contribute a quantity of money periodically to the group to form a common fund that will give loans among their own members. Given that most of the population is illiterate, the primary objective of the project was to help these groups improve their financial skills to understand the fundamentals of how cooperatives work, as well as gaining a basic knowledge of budgeting and operational control. This allows them to generate profits for themselves and have access to liquidity to cover their basic survival needs, as well as enable members to access micro-loans for investment provided by the group (Interviewees 20 and 21).

4.3.3. Fundación AFI, Madrid

Fundación AFI is a NPO created by Analistas Financieros Internacionales (AFI) in 1999. Its mission is to promote financial education, innovation and inclusion in Spain and developing countries.

In 2014 AFI published a very interesting book with Fundación Telefónica called “Microfinanzas y TIC. Experiencias Innovadoras en Latinoamérica” that cover the future challenges of MFIs and TICs (Interviewee 22).

4.3.4. Inversión and Cooperación" (I&C)

“Inversión and Cooperación” (I&C), is a private foundation born from a Spanish family business group, Expert Timing Systems (ETS)1 specialized in financial advisory and TechRules2 a financial technology company.

It is our goal since the beginning to leverage on these 30 years expertise through our foundation to promote social inclusion through financial education and technology at the base of the pyramid (Interviewee 23).

They believe that trust among families and friends are a commonly underestimated key human value on which strong self-sustainable cooperation projects can be developed. However, most cooperation projects today fail to respect this critical principle of respect, thus harming sustainability self-sufficient persons, families, communities and countries. Lending money without previous education and savings habits or giving goods for free generate dependency and bad habits.

I&C designed a program called “Saving for Learning” based on the community lending groups model with the purpose of start a trend of self-sustainable improvement in the quality of life of families leaving in poverty. It is a way to provide an alternative financing to the oppressive regime of traditional moneylenders, that was the only source of credit available (Interviewee 23).

Educating to generate long-term saving habits and management skills is our challenge. We have designed a practical financial education program based on a safe flexible, transparent, inexpensive and profitable way to save. Targeting groups of 10 to 50 people linked by strong bonds of trust. I&C applies a Self-finance and self-managed socio-economic inclusion model which doesn't begin by external credit, but by promoting community savings. A solution based on four pillars: financial education, self-financing through savings, self-management and technology (Interviewee 23).

I&C decided to apply new ICT technologies to make financial services more accessible, convenient and safe and developed an advanced cloud-mobile technology. The main purpose of the platform is to help group members to manage their weekly meetings more efficiently (savings, paid-in capital, loans, interest received and due) and to improve financial education by new innovative cost-effective teaching methods. In addition, the Qmobile online platform is used to train program coaches (Interviewee 24).

The "Saving for Learning" program is implemented in Peru and Ecuador. Ecuador is the largest one with has more than 400 savings groups and 9.000 members. All without the intervention of any credit officers. Managed by the groups themselves with the advice of our coaches. The main beneficiaries of these savings groups are vulnerable woman (Interviewee 25).

4.3.5. Acción Emprendedora, Perú

“Acción Emprendedora” () is a team of volunteer professionals committed to the development of Peru. Their mission is to transmit knowledge in business management to entrepreneurs by necessity, so that they have more opportunities to success. Their vision is to transform the lives of Peruvian micro-entrepreneurs through a business development program which links the best of their talent with the knowledge and experience of volunteer professionals. Entrepreneurs can access specialized training programs given by experience volunteers, they share their talent by joining the professional team of advisors, teachers and mentors (Interviewee 26).

4.4. Other institutions

4.4.1 ESAN University Peru

This university has an important role in Higher Education and collaborate in several educational projects targeted to woman in rural areas like "Project Pro-Mujer". Pro-Mujer is a women’s development program with counselling sessions related to health, food and basic education. They use mobile clinics to reach clients and their families living in remote areas. We believe that if we help woman it can transform the lives of their families that become healthier and more educated (Interviewee 27).

Individuals are increasingly using mobile to access many different services, but half of the Peruvian population are still unable to take full advantage of the services potentially available. The Internet coverage in Peru rural areas has increased in the past few years thanks to the high investment and government support. I believe that ICTs will help improving financial inclusion with less expensive financial services. ICTs revolution will help rural population accessing education, public services and digital payments (Interviewee 28).

The university is also involved in entrepreneurship programs delivered by university students as part of their social responsibility program (Interviewee 29).

5. Findings Discussion, Recommendations and Conclusions

5.1. Findings discussion

The main findings from these interviews with local MFIs and other microfinance institutions making a traceability of each result with the issues arisen in the interviews which are the following:

Firstly, they all agree that, the MFIs relational model is very expensive given the number and size of loans, and that many customers live in remote rural areas. Banking agents or front-line officers are the sales force, the revenue generators and the MFI’s interface with clients, therefore training and retaining them should a priority (Interviewees 1,4,5,9,10 and 11).

Secondly, the low customers retention rate reported by FC, only 20 per cent of their customers remain with the MFI for more than 2 years (Interviewees 1,4,5 and 6). Clarity of the underlying factors of drop out is essential in order to re-address the MFI efforts in terms of customer experience, product flexibility, financial education. Some of the reasons for drop out are health problems, business failure, group problems and that banking officials move to another MFI and take their customers with them (Burgon et al., 2012). Given that client contact relies heavily on the banking agents, retention and training programmes of these agents are vital.

Thirdly, intense competition in Peru is causing over-indebtedness and a high customer rotation (Interviewees 1,4,11 and 16). A 2010 report carried out by the Centre of Microfinance at the University of Zurich, highlighted the risk of over-indebtedness in Peru in line with Kappel et al. (2010) and McIntosh & Wydick (2005). In 2016, Smart Campaign published a report on Peruvian consumers showing that rural consumers spend 35 per cent of their monthly income on debt repayment and 16 per cent are late on their payments.

Fourth, people in rural areas resist opening accounts because of the lack of trust in the financial system and other reasons. Becoming part of the financial system requires customers to change their habits and increase trust on institutions which can take time (Interviewees 2,8,14 and 17).

Fifth, all interviewees agree that education is the only tool that can improve situations of vulnerability and improve the microcredit impact, in line with Kaiser & Menkhoff (2017) and Karlan & Valdivia (2011). Educational materials should cover the following issues: Differentiate family and business accounts, how to use a saving account, improving trust in financial institutions, basic accounting (recording transactions, cash-flows and budgeting process) and selling and marketing (Interviewees 12 and 13).

In addition, training methodology should be adapted to local cultures and be provided at relevant moments, for example with credit. Given that front-line officers work with customers trying to produce pro-forma financial statements and complete the credit application form is an excellent moment to train them in accounting and financial products (Interviewees 5 and 8). Another interesting finding is that most MFIs had developed different types of training programmes with high involvement of university students and lecturers, this is a way to bridge the gap between Higher Education Institutions and the real world in line with Yunus (2003).

If training is well designed, it will have a positive impact (Fiala, 2018; Masino & Niño-Zarazúa, 2016; Drexler et al., 2014). Its primary role is to provide essential information on financial products and how to manage cash-flow (Interviewees 1,4,10,12,14,20,23,26,27 and 29).

The interviewees pointed out that governments should be responsible for providing an appropriate institutional framework (Interviewees 12,14 and 22), in line with Acemoglu & Robinson (2012). Trust in the institutions, regulatory environment, modern infrastructure and communications, are among the conditions that play a key role in improving financial inclusion. Corporate governance is another important issue (Interviewee 17). MFIs must consider whether the whole organisation is achieving their mission efficiently and sustainably (Gutierrez-Goiria et al., 2017). Government and banking institutions should work together to increase digital financial inclusion within an appropriate framework. A good example of cooperation is the “Billetera Móvil” (BIM) project (Interviewees 12,14 and 15), a digital payment product that has recently been launched in Peru. They aim to improve the use of digital and mobile technologies as a tool to increase financial inclusion.

One recent example of public-private collaboration in Latin-American is the Locfund Next: the first permanent regional vehicle, managed by local managers, dedicated to provide local funding and digital transformation support to MFIs. Google funded $8 million through the Inter-American Development Bank's Innovation Lab (IDB Lab) that additionally provided $4.5 million. This increases the capital available for SMEs to access formal microcredit and, as a result, strengthen their economic recovery and accelerate the post-COVID-19 economic recovery process (IDB Lab News, 2021).

5.2. Recommendations

Based on the interviews, results discussion, research reports and fieldwork in Peru, we define some broad recommendations in relation to financial inclusive products and financial education programmes. We will differentiate our target population by the level of poverty: extreme poverty (less than US$1.9 a day), poor population (less than US$3 a day) and vulnerable (between US$3 and US$10 a day) (Interviewees 12 and 13). Each group will receive a different type of education. Traditional financial education can impact some financial behaviours, but it is very expensive and not very effective (Kaiser & Menkhoff, 2017). The impact of training programmes improves when tuition is adapted to the micro-entrepreneur’s needs (Bali & Varghese, 2013). However, the cost of providing individual financial education can be prohibitively high. In addition, it is difficult to persuade many people to attend these programmes. Therefore, it is necessary to design cost-effective training programmes using ICTs (Interviewees 11,15,22,23,24 and 28) (Ontiveros et al., 2014, Kauffman, & Riggins, 2012).

Our first recommendation is to establish differentiated strategies for different levels of poverty (Interviewees 8 and 9). Depending the level of poverty, different approaches in terms of products and financial and accounting education should be offered in order to optimise financial inclusion. In addition, education programmes should be simple and attractive, personalised to individual’s needs, and, ideally, in line with their specific financial decisions. The following table shows the type of education that should be offered depending the level of poverty (Table 2).

Table 2. Financial inclusive Education per level of poverty

| Education Program | Extremely Poor | Poor | Vulnerable |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic training on skills |  | ||

| Introduction to financial products |  |  | |

| Basic accounting and financial education |  |

Source: Author’s own.