Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility Orientation: From Gathering Information to Reporting Initiatives

ABSTRACT

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) strategies have become an important research topic in recent years as they can generate numerous benefits for organizations, especially when an adequate market orientation (MO) has been defined. In this sense, several research questions arise: do companies have enough CSR information to implement appropriate strategies? Does the information that they have gathered allow them to define a complete set of CSR activities (response) based on the triple bottom line approach? And, once they have carried out their initiatives, do these companies ensure adequate dissemination of the results to stakeholders?. In order to answer the above questions, this study sought to examine companies’ CSR orientation from a MO perspective. Working with data on a sample of 165 firms in Spain, during January 15th and February 15th, 2017, structural equation modeling was used to test a set of research hypotheses. The results reveal an important link between information, response, and diffusion and help extend the MO strategy concept. CSR information has a positive, direct influence on the development of initiatives covering three dimensions (economic, social and environmental). In addition, a direct relationship exists between the development of social and environmental initiatives and CSR disclosure. This research’s findings contribute to the literature on interest groups and business sustainability. Also, they confirm that the development of social and environmental initiatives contributes positively to CSR dissemination and to the generation of competitive advantages. This way, collecting CSR information constitutes a valuable asset. With respect to the limitations of the study, the answers reflected each SME leader’s subjective opinion, the variables’ measurement was dealt with through reflective models using the PLS technique based on variance and only Spanish companies already oriented toward CSR participated in the study.

Keywords: Corporate social responsibility, information, diffusion, market orientation, partial least squares (PLS).

JEL classification: M14, M41.

Orientación estratégica de la Responsabilidad Social Corporativa: de la recopilación de información a la difusión de las actuaciones

RESUMEN

Las estrategias de responsabilidad social corporativa (RSC) se han convertido en un tema de investigación importante en los últimos años, ya que pueden generar numerosos beneficios para las organizaciones, especialmente cuando se ha definido una orientación adecuada al mercado (OM). En este sentido, nos surgen varias preguntas de investigación: ¿disponen las empresas de suficiente información de RSC para implementar adecuadas estrategias? ¿la información que poseen les permite definir un conjunto de actividades de RSC (respuesta) basadas en el enfoque del triple bottom line? Y, una vez que han llevado a cabo sus iniciativas, ¿estas empresas aseguran una adecuada difusión de los resultados a los grupos de interés?. Con el fin de dar respuesta a las anteriores cuestiones, este estudio buscó examinar la orientación de la RSC de las empresas desde una perspectiva OM. Trabajando con datos de una muestra de 165 empresas en España, durante el período comprendido desde el 15 de enero al 15 de febrero de 2017, se utilizaron los modelos de ecuaciones estructurales para probar un conjunto de hipótesis de investigación. Los resultados revelan un vínculo importante entre la información, la respuesta y la difusión y ayudan a extender el concepto de estrategia de OM. La información de RSC tiene una influencia positiva y directa en el desarrollo de iniciativas que cubren las tres dimensiones (económica, social y medioambiental). Además, existe una relación directa entre el desarrollo de iniciativas sociales y ambientales y la divulgación de la RSC. Los hallazgos de esta investigación contribuyen a la literatura sobre grupos de interés y sostenibilidad empresarial. Además, confirman que el desarrollo de iniciativas sociales y ambientales contribuye positivamente a la difusión de la RSE y a la generación de ventajas competitivas. De esta manera, la recogida de información de RSE constituye un activo valioso. Con respecto a las limitaciones del estudio, las respuestas reflejaron la opinión subjetiva de cada líder de las Pymes, la medición de las variables se trató a través de modelos reflectivos utilizando la técnica PLS basada en la varianza y solo las empresas españolas ya orientadas hacia la RSE participaron en el estudio.

Palabras clave: Responsabilidad social corporativa, información, difusión, orientación al mercado, partial least squares (PLS).

Códigos JEL: M14, M41.

1. Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) has become an important research topic in recent decades (Gallardo-Vázquez & Sánchez-Hernández, 2014a, 2014b; Valdez-Juárez, Gallardo-Vázquez, & Ramos-Escobar, 2018). CSR is clearly a strategy of imperative interest to all organizations, especially to large and small firms (Blanc, Branco, & Patten, 2019; Martínez-Martínez, Herrera, Larrán, & Lechuga, 2017; Moneva-Abadía, Gallardo-Vázquez, & Sánchez-Hernández, 2018). An extensive literature already exists that discusses the benefits companies can receive from carrying out socially responsible initiatives. In CSR’s internal sphere, CSR promotes social consciousness in corporate culture, increasing employees’ involvement and commitment to their organization (e.g., Hao, Farooq, & Zhang, 2018; Jones, 2010; Turker, 2009a, 2009b). The literature also contains frequent mentions of reputation as a valuable, all-embracing resource strongly linked to socially responsible activities (Baldarelli & Gigli, 2014; Jo, Kim, & Park, 2015). In addition, CSR increases productivity, sales, and profits. Organizations’ CSR practices facilitate the achievement of better performance and financial results, thereby positively affecting productivity, competitiveness, and competitive success (Boulouta & Pitelis, 2014; Gallardo-Vázquez & Sánchez-Hernández, 2014a; Rodrigo, Durán, & Arenas, 2016). More recently, Hameed et al. (2016) have asserted that CSR initiatives can generate increased performance and value.

Thus, CSR is associated in the literature with numerous variables such as commitment, culture, image, reputation, competitive success, productivity, and performance. At the same time, the literature indicates that companies have little information, that is, they have little knowledge about what CSR is and how to put it into practice. Likewise, the disclosure of CSR carried out by companies is not very abundant. Therefore, it seems that the literature has delved into the actions carried out by companies, but not in the information possessed and in the disclosure made. So, a necessary starting point is to determine the level of CSR information that companies possess before they implement CSR strategies in the three dimensions (economic, social and environmental), because having some information about CSR makes companies to be engaged in CSR, and once they are involved, the next step is to communicate it. A gap was observed in the literature regarding the information possessed and the level of CSR diffusion. All these aspects are key in a market orientation (MO) strategy, which as we know consists of three steps: information, diffusion and response. Therefore, since the response is more elaborated in the previous literature, we wanted to delve into the less worked steps, information and diffusion. This underresearched topic was selected as the present research’s focus. The present study, therefore, sought to answer the following research questions (RQ):

RQ1: Do companies have enough CSR information to implement appropriate strategies?

RQ2: Does the information that they have gathered allow them to define a complete set of activities based on the triple dimension approach?

RQ3: Once they have carried out initiatives, do these companies ensure adequate dissemination of the results to stakeholders?

To address these questions, this study aimed, first, to achieve a better understanding of the relationships between CSR information’s effects and the development of CSR initiatives in three dimensions (i.e., economic, social, and environmental). This objective addressed the first two RQs raised (i.e., RQ1 and RQ2). Second, the research included analyzing the link between these initiatives’ development and their diffusion, thus focusing on the third research question (i.e., RQ3). This study relied on structural equation models (SEMs) and applied the PLS technique to analyze data on a sample of 165 Spanish companies headquartered in the Autonomous Community of Extremadura.

The results extend the existing knowledge—from a sustainability perspective—about the MO concept developed by Kholi & Jaworski (1990) and Narver & Slater (1990). Although previous research (Bello, Halim, & Alshuabi, 2018; Gallardo-Vázquez & Sánchez-Hernández, 2014b; Kiessling, Isaksson, & Yasar, 2016; Sánchez-Hernández, Carvalho, & Paiva, 2019) has linked MO with CSR, the present study went beyond the existing investigations to examine the relationship between information possession and dissemination, which are both dependent on the development of socially responsible initiatives in the triple dimension. In order to highlight the contribution of this paper with respect to the previous literature, we note that the defined conceptual model is broader, incorporating in the response, the three dimensions of CSR, economic, social and environmental, going beyond the study of Gallardo-Vázquez & Sánchez-Hernández (2014b). Also, this paper has focused on the dynamic capabilities and stakeholders theories, which are an extension of the theoretical approach used in Gallardo-Vázquez & Sánchez-Hernández´s study (2014b), and making a very up-to-date presentation of MO and its extension towards CSR and therefore going much further than previous authors. Moreover, in this paper, the market concept has been extended to include multiple interest groups (e.g., customers, shareholders, managers, and employers) (Gallardo-Vázquez & Sánchez-Hernández, 2014b; Sánchez-Hernández et al., 2019). Also, the authors have presented a broader conceptual model, incorporating in the response, the three dimensions of CSR, economic, social and environmental, going beyond the study of Gallardo-Vázquez & Sánchez-Hernández (2014b).

The findings can be considered a significant contribution to the literature because they can help managers control the information they generate during their firms’ implementation of CSR practices and determine the level of dissemination needed. We consider that the focus of this work under the MO is adequate since it analyzes in depth the three components of said orientation (information, response or actuation, and dissemination or diffusion (Kholi & Jaworski, 1990) under the CSR perspective. The results indicate the validity of the approach and the contribution of the study.

With respect to the novelty of the study, we have to say that given the current emphasis on sustainability, researchers have sought to define possible relationships between MO and socially responsible practices contributing to the achievement of sustainable performance. Prior literature have found a link between CSR and marketing, stating that MO significantly improves performance (Oduro & Haylemariam, 2019). At the same time, CSR improves stakeholders´s perceptions (Barone, Norman, & Miyazaki, 2007). Last contributions link MO and CSR from marketing perspective and performance, but we would like to extend to the CSR information and diffusion constructs. This way, we consider that this study is new and interesting relative to the prior literature. At the same time, this paper adds new empirical evidence to the study of stakeholders and dynamic capabilities theories.

The selected research topic’s importance and the advantages of CSR can bring to organizations have motivated on-going investigation over the years, leading to the incorporation of new visions and perspectives into the existing literature. The present study’s results contribute to the literature on CSR strategies establishing how the fact of having CSR information will determine the development of initiatives in the triple bottom line approach. More specifically, the findings focus on Spanish companies that show an orientation toward CSR, which is a current topic in this field. Also, they confirm that the development of social and environmental initiatives contributes positively to CSR dissemination and to the generation of competitive advantages. This way, collecting CSR information constitutes a valuable asset.

This paper is organized as follows. The next section presents the theoretical background focused on MO and its extension through CSR. The hypotheses are then defined, as well as how they were used to develop the proposed conceptual model. The methods are subsequently described including the sample and data, variables, and measurement scales. The results are detailed, and, finally, the discussion, conclusions, and limitations are presented, together with possible lines of future research.

2. Theoretical background and hypotheses’ rationale

2.1. Stakeholder and dynamic capabilities theories

The current globalized market has changed businesses’ perspective from a focus on maximizing owners and/or shareholders’ value (Martínez-Ferrero, 2014) to a vision that combines simultaneously complex and varied interactions between multiple stakeholders (Kiessling et al., 2016). This new perspective concentrates on the individuals or groups that benefit from or that are harmed by corporate actions (Freeman, 1998) and that contribute to the creation and distribution of economic value (Asher, Mahoney, & Mahoney, 2005). These groups need to be considered in management-level decision making (Freeman, 1999), including, among others, owners, employees, customers, suppliers, local communities, and governments. This set of relationships is formalized in contracts defining rights, objectives, expectations, and responsibilities and thereby configuring organizations’ current operational models (Fassin, de Colle, & Freeman, 2016; Walsh, 2005) so that their success depends on properly managing these relationships (Freeman & Philips, 2002).

Although the stakeholder theory has sometimes been criticized for having a weak empirical base and explanatory power (Frynas & Yamahaki, 2016), this theory has been incorporated into many studies on CSR. The latter business strategy has gained interest and topicality in response to increased pressure from interest groups (Martínez-Martínez et al., 2017; Öberseder, Schlegelmilch, & Gruber, 2011). In this context, experts need to take into account the importance of developing a comprehensive discourse with stakeholders and incorporating their responses into globalization scenarios (Richter & Dow, 2017). Very recently, Vaitoonkiat and Charoensukmongkol (2020) investigate stakeholder orientation´s influence on firm´s performance from a MO perspective.

Dynamic capabilities theory has its roots in resource-based theory, with this new approach seeking to take companies to a higher level of responsibility with a dual-benefit approach (i.e., company-society). In addition, this theory includes the detection and exploitation of opportunities in potential markets, helping organizations’ execute and apply internal and external resources to achieve sustainable results (Kachouie, Mavondo, & Sands, 2018; Teece, 2007). Strategic capabilities include MO and CSR, which have become pillars sustaining most organizations’ growth and competitiveness—whether they are small or large—over the last two decades (Ledesma-Chaves, Arenas-Gaitan, & García-Cruz, 2020; Teece, 2018).

A key dynamic capability for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) is the process of generating knowledge, which facilitates the execution of strategic plans (Sarkar, Coelho, & Maroco, 2016). Resources and knowledge, such as information, stimulate dynamic capabilities development (Bitencourt, Santini, Ladeira, Santos, & Teixeira, 2020). A crucial CSR practice is the dissemination of information about the CSR activities companies develop. Therefore, CSR plans not only obtain internal and external information about company practices in social and environmental initiatives but also detect social problems related to the companies in question (Dentoni, Bitzer, & Pascucci, 2016; Zbuchea & Pînzaru, 2017). These initiatives contribute to generating more accurate reports on responsible firms’ effects on their stakeholders (Galbreath, 2009; Ramachandran, 2011). However, many organizations have various internal limitations on their ability to develop CSR plans (Galbreath, 2009). After the two above-mentioned theories’ contributions were weighed, MO’s fundamental principles were examined, including how they extend into CSR practices, as discussed in the next subsection.

2.2. Market Orientation (MO)

Performance improvement is clearly an objective that all organizations seek to achieve, but the strategies implemented to achieve it have been extremely varied. In marketing (Jogaratnam, 2017; Kajalo & Lindblom, 2015), MO has been extensively studied, and this strategy has been extended to other organizational areas, reflecting the interdisciplinary approach that currently prevails. Kajalo & Lindblom (2015) and Zehir, Köle, & Yıldız (2015) point out that MO improves organizational performance and generates competitive advantages. Other authors have also found evidence of a significant positive link between MO and performance (Bhatia & Jain, 2015; Protcko & Dornberger, 2014). Wang, Zhang, & Song (2020) study the environmental conditions under which a MO strategy is more advantageous for firm´s performance. More specifically, researchers have reported a link between MO and profitability (Raju, Lonial, & Crum, 2011; Smirnova, Naudé, Henneberg, Mouzas, & Kouchtch, 2011) and MO and net sales and operating profit (Vega-Rodríguez & Rojas-Berrio, 2011).

MO is a business philosophy with a specific perspective on how organizations adapt to their customer environment in order to achieve competitive advantages (Kohli & Jaworski, 1990; Liao, Chang, Wu, & Katrichis, 2011; Slater & Narver, 2000). Kholi and Jaworski (1990, p. 6) define MO as “the organization wide generation of market intelligence pertaining to current and future customer needs, dissemination of the intelligence across departments, and organization wide responsiveness to it.” The cited authors based their conceptualization of MO on three subconstructs. The first is the generation of market intelligence, which includes an analysis of customers’ needs and preferences. The second is this intelligence’s dissemination or disclosure within firms, which is an important step because the information constitutes a shared company value. The last subconstruct is firms’ responsiveness to this market intelligence. In this context, companies obtain information on customers’ present and future needs, act on that knowledge, and offer better services (Slater & Narver, 2000). Efficient and effective services delivered to interested parties contribute to the satisfaction of changing market needs (Lechuga-Sancho, Martínez-Martínez, Larrán, & Herrera, 2018).

Narver & Slater (1990) further distinguished between three dimensions in MO: customer orientation, competitor orientation, and inter-functional coordination. Customer orientation focuses on knowing clients’ needs, which allows companies to meet these needs and provide customers with superior value. This orientation places clients at the center of organizations’ activities, helping firms achieve greater profitability and customer retention (Brady & Cronin Jr., 2001).

Competitor orientation implies that companies can analyze and understand their rivals by paying greater attention to their activities before making decisions (Narver & Slater, 1990). This approach focuses on creating differentiation in the market (Grinstein, 2008; Im & Workman Jr., 2004) and obtaining competitive advantages and sustainable performance. Finally, inter-functional coordination implies communication practices that can help firms improve their services (Grinstein, 2008). Offering better services to customers, identifying competitors’ strategies, and coordinating communication and interactions are signs of an adequate MO capable of generating benefits and achieving advantages over the competition (Narver & Slater, 1990).

Given the current emphasis on sustainability, researchers have sought to define possible relationships between MO and socially responsible practices contributing to the achievement of sustainable performance. Oduro and Haylemariam’s (2019) work found a link between CSR and marketing in manufacturing companies in Ghana and Ethiopia. The cited authors’ findings include that MO significantly improves performance, with different effects depending on the country in question and the level of CSR implemented. Concurrently, CSR generates more humanistic market-oriented activities (Barone, Norman, & Miyazaki, 2007; Du, Bhattacharya, & Sen, 2007), thereby improving stakeholders’ perceptions. Jiang, Rosati, Chai, & Feng´s paper (2020) applies the OM perspective in its connection with the creation of knowledge and environmental performance in Chinese companies. The authors conclude that the creation of knowledge (information in our case) mediates the influence of customer orientation on environmental performance. This highlights the importance of having information.

2.3. Extension of MO into CSR

Pressures from various interest groups have motivated organizations to pay more attention to CSR strategies (Öberseder et al., 2011). Companies now need to apply a broader market approach to achieve their objectives (Kang, 2009; Luo & Battacharya, 2009) due to better organized customers who have more information, which makes them more demanding and more interested in the implementation of socially responsible initiatives. CSR has thus become a vital strategy for companies (Bondy, Moon, & Matten, 2012; Carroll & Shabana, 2010), as well as a strategic marketing component of great importance to competitive success (Carroll & Shabana, 2010; Kiessling et al., 2016; Luo & Bhattacharya, 2009).

Luo and Bhattacharya (2009) suggest that the current prevalence of the MO perspective causes customers to prefer CSR-focused companies that, when they have the knowledge to do so, will implement CSR strategies. In short, the literature on MO and CSR suggests not only a direct effect on financial performance but also indirect—and sometimes difficult to quantify—impacts such as customer loyalty and stronger relationships with stakeholders (Du, Bhattacharya, & Sen, 2010; Kirca, Jayachandran, & Bearden, 2005). The present study used the MO perspective to gain a clearer, fuller understanding of firms’ CSR strategies (Kholi & Jaworski, 1990; Narver & Slater, 1990).

Given the current interest in the link between MO and CSR, Gallardo-Vázquez & Sánchez-Hernández (2014b) and Sánchez-Hernández et al. (2019) work relied on Kholi & Jaworski (1990) and Narver & Slater's (1990) conceptualization of MO to examine CSR more closely. More specifically, Gallardo-Vázquez & Sánchez-Hernández (2014b) and Sánchez-Hernández et al. (2019) adapted marketing concepts and strategic approaches to explain CSR orientation models more fully, as have other authors (Bello et al., 2018; Kiessling et al., 2016). As noted previously, the original understanding of MO included satisfying customers’ needs (Kholi & Jaworski, 1990; Narver & Slater, 1990). From this perspective, every organization must carry out initiatives that take into account the relevant stakeholders. To define the MO construct from a CSR perspective, the market concept has been extended (Gallardo-Vázquez & Sánchez-Hernández, 2014b) to include multiple interest groups (e.g., customers, shareholders, managers, and employers).

As mentioned previously, Gallardo-Vázquez & Sánchez-Hernández (2014b) addressed MO from the CSR perspective by expanding the stakeholder orientation and affirming that MO is related to the use of CSR information. The cited authors defined a conceptual model of causal relationships between three variables—information, dissemination, and environmental response—to evaluate CSR-related MO. Kiessling et al. (2016) also used the MO framework as a theoretical foundation in their exploration of CSR. The cited researchers postulate that firms gather knowledge about their customers’ needs because they are vital stakeholders, and this information allows companies to carry out new CSR activities and achieve competitive advantages.

Based on this theoretical framework, Bello et al. (2018) developed an analytical model of the direct relationships between MO dimensions and sustainability performance. Sánchez-Hernández et al. (2019) further defined a composite model of information, diffusion, and response for African firms. The cited authors argue that companies get CSR information from their markets and that firms coordinate their resources internally and offer responses to stakeholders’ needs. Through this process, companies become market-oriented and co-create value through CSR strategies.

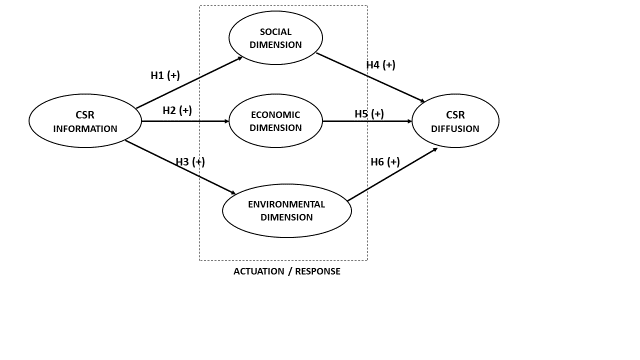

Thus, applying Kholi & Jaworski's (1990) approach to MO provides organizations with a unifying approach that contributes to improved performance and other potential benefits. The present study’s conceptualization of MO included this sustainable approach (Gallardo-Vázquez & Sánchez-Hernández, 2014b; Kiessling et al., 2016; Sánchez-Hernández et al., 2019). Within the CSR framework, MO can be contextualized in three dimensions: information, response or actuation, and dissemination or diffusion (Gallardo-Vázquez & Sánchez-Hernández, 2014b; Kholi & Jaworski, 1990). These formed the three pillars for the current research’s conceptual model (see Figure 1).

In this approach, MO is supported by the application of stakeholder theory, which seeks to define how multiple interest groups can be satisfied. Concurrently, the proper management of resources based on an application of dynamic capabilities theory generates value creation with multiple benefits for organizations. After developing the above theoretical framework, the hypotheses that support the conceptual model were formulated.

2.4. CSR information and CSR initiatives

Information is without question an important asset necessary to manage according to the dynamic capabilities theory. The European Commission (EC) highlights information’s importance to businesses in its report “European SMEs and Social and Environmental Responsibility” (EC, 2002). In addition, the study “CSR Communication: Talking to People Who Listen” published by APCO Worldwide (2004) also emphasizes the significance of CSR information to companies. Many authors have since focused on CSR information (Fisher, Geenen, Jurcevic, McClintock, & Davis, 2009; Hammann, Habisch, & Pechlaner, 2009; Nielsen & Thomsen, 2009; Patenaude, 2011; Vidal, Bull, & Kozak, 2010). According to Liu, Li, Quan, & Yang (2019), information has become a crucial commodity able to detect opportunities in potential markets, as indicated by the theory mentioned above.

In addition, information is a necessary asset for companies seeking to develop CSR activities among the different interest groups and for the benefit of them, as indicated by the stakeholders theory. Without information, firms encounter difficulties in carrying out these initiatives. Gallardo-Vázquez & Sánchez-Hernández (2014b) found evidence of a direct, positive relationship between the CSR information gathered by SMEs and their environmental initiatives. The cited authors were also able to corroborate a direct, positive relationship between CSR information and SMEs’ disclosure of their environmental initiatives. Thus, having CSR information facilitates the carrying out of initiatives based on this strategy, achieving the satisfaction of all stakeholders.

However, Liu et al. (2019) report that the privatization of the cost of gathering CSR information has had a negative impact on the sustainable development of this information’s supply chain. Nonetheless, according to Kholi & Jaworski (1990), companies need to carry out initiatives or develop responses based on the triple bottom line approach (Jeurissen, 2000), which takes into consideration three dimensions: economic, social, and environmental, oriented to achieve an adequate application of resources as indicated by the dynamic capabilities theory.

More recent studies have found the CSR information possessed by innovative companies whose leadership engage in behaviors focused on sustainability—as defined by interest groups—has become a key factor in generating greater confidence and legitimacy. These strategies have also generated more economic benefits (Duff, 2017; Ghouri, Akhtar, Shahbaz, & Shabbir, 2019). However, some SMEs (i.e., mostly family-owned) still do not have as much CSR information as large organizations, which prevents these SMEs from implementing CSR initiatives and puts these companies at a disadvantage (Cabeza-García, Sacristán-Navarro, & Gómez-Ansón, 2017; Steinhöfel, Galeitzke, Kohl, & Orth, 2019). Specific contexts have allowed different SMEs from regions with highly developed economies to collect CSR information that allows these firms to include CSR practices in their strategic plans from the generation of knowledge derived from that CSR information, as postulated by the aforementioned theory (Campos & Grangel, 2019; Cea, 2019).

Recently, the digital transformation process has had a further positive effect, and companies that avoid stagnation and fight to be more innovative through their initiatives can gather more information in different ways and use it to help implement CSR initiatives, looking for a better application of resources (dynamic capabilities theory). More specifically, big data is of great value to companies that need to penetrate communities and groups of interest quickly, generating satisfaction for stakeholders and maximizing value for all (stakeholders theory) (Corazza, 2019; Sivarajah, Irani, Gupta, & Mahroof, 2019). Based on the existing research, the present study proposed the following hypotheses:

H1: CSR information has a direct, positive influence on the development of social dimension initiatives.

H2: CSR information has a direct, positive influence on the development of economic dimension initiatives.

H3: CSR information has a direct, positive influence on the development of environmental dimension initiatives.

As we can deduce, this first three hypotheses lead to achieve a better understanding of the relationships between CSR information’s effects and the development of CSR initiatives in three dimensions (i.e., economic, social, and environmental). This way, the first two RQs raised (i.e., RQ1 and RQ2) are addressed. That is to say, companies that have enough CSR information to implement strategies will be able to define a set of actions based on the triple dimension approach.

2.5. CSR initiatives and CSR disclosure

Companies disseminate information about their social, economic, and environmental impacts inside and outside of their organization, namely, as CSR disclosure (Brunton, Eweje, & Taskin, 2017; Thijssens, Bollen, & Hassink, 2015), which has been extensively researched. The CSR disclosure process is voluntary, and it is based on the guidelines of existing standards (Bhaduri & Selarka, 2016) and supported by the Global Reporting Initiative.1 These standards help companies to implement and manage information about their CSR practices, thereby offering responses to their stakeholders’ questions about firms’ impacts on society and allowing companies to provide proof of their legitimacy, seeking the satisfaction of all stakeholders, as indicated by the stakeholders theory (Brunsson, Rasche, & Seidl, 2012; Vigneau, Humphreys, & Moon, 2015). The dissemination of CSR practices is carried out via sustainability reports.

Companies’ reporting strategy is determined by numerous factors, such as their sector, market, firm size, and corporate ownership (e.g., Reverte, 2009; Thanasanborrisude & Phadoongsitthi, 2015). The existing literature further reports that CSR disclosure is directly and positively related to profitability (Gamerschlag, Möller, & Verbeeten, 2011). Siueia, Wang, & Deladem (2019) found a significant positive relationship between financial performance and CSR disclosure, suggesting that CSR behaviors help improve banks’ performance. Kouloukoui et al. (2019) also contend that corporate disclosure has a significant positive relationship with firm size, financial performance, and country of origin. However, CSR disclosure has a negative association with level of indebtedness.

Recent studies have shown that disclosure currently is not transparent enough and that it provides inadequate information about companies’ CSR practices, which weakens these firms’ image and reputation (Gangi, Meles, Monferrà, & Mustilli, 2018; Johnstone, 2019). In general, strategic decisions about disclosure are made by shareholders because most SMEs rely on a more robust business model of CSR initiatives. This approach motivates organizations to gather and disseminate information on CSR’s social, economic, and environmental impacts on stakeholders, applying resources on the one hand (dynamic capabilities theory) and generating satisfaction on the other (stakeholder theory) (Ramón-Llorens, García-Meca, & Pucheta-Martínez, 2018; Tsalis, Stylianou, & Nikolaou, 2018).

Although more developed countries have regulations that mandate the full, transparent dissemination of CSR results through reports, many SMEs have not yet complied with these laws (Andrades & Larrán, 2019; Andrades, Martínez-Martínez, Larrán, & Herrera, 2019). In addition, in times of crisis and economic recession, companies tend to focus on promoting internal CSR initiatives and solidifying their corporate governance while neglecting social initiatives. These firms give little importance to employee assets and invest few of their financial resources in environmental initiatives, which results in a loss of interest in reporting and disseminating CSR results (Larrán, Andrades, & Herrera, 2019; Sakunasingha, Jiraporn, & Uyar, 2018).

The present study thus proposed these hypotheses:

H4: A direct, positive relationship exists between the development of social dimension initiatives and CSR diffusion.

H5: A direct, positive relationship exists between the development of economic dimension initiatives and CSR diffusion.

H6: A direct, positive relationship exists between the development of environmental dimension initiatives and CSR diffusion.

This three hypothesis lead to analyze the link between these initiatives’ development and their diffusion, thus focusing on the third research question (i.e., RQ3). In this sense, once companies have carried out their initiatives, they should ensure adequate dissemination of the results.

Figure 1 presents the hypothesized relationships tested in this research.

Figure 1. Conceptual model and hypotheses

Source: Authors

3. Methods

3.1. SEMs

SEMs were used to test the conceptual model proposed. To this end, the partial least squares (PLS) statistical technique was applied with the help of SmartPLS 3.2.8 Professional Full Version software (Ringle, Wende, & Becker, 2014). The present study’s models were based on an econometric perspective oriented toward prediction and focused on latent or unobserved variables, which were inferred from indicators (Chin, 1998b). These models are considered second generation multivariate models that allow, first, the incorporation of abstract constructs not directly observable. Second, the models facilitate the determination of the degree to which measurable variables describe latent variables, and, third, SEMs incorporate relationships between multiple predictor variables and criteria. Last, the models combine and test hypotheses emanating from previous theoretical knowledge based on data collected empirically (Chin, 1998a).

Numerous investigations have used this technique in the social sciences and, more specifically, addressed the study of CSR in SMEs, as the current research did. Of particular note are the studies by Gallardo-Vázquez & Sánchez-Hernández (2014a); Gallardo-Vázquez et al. (2013); Herrera-Madueño et al. (2016); López-Pérez, Melero, & Sese (2017), and Valdez-Juárez (2017). In addition, SEM methodology has been applied to the relationships between CSR and other variables in SME contexts, such as performance (Herrera-Madueño et al., 2016, Reverte, Gómez-Melero, & Cegarra-Navarro, 2016), competitiveness (Marín, Rubio, & Ruiz, 2012, Yu, Kuo, & Kao, 2017), and innovation (Martínez-Conesa, Soto-Acosta, & Palacios-Manzano, 2017; Rexhepi, Kurtishi, & Bexheti, 2013). The extensive application of the PLS technique gives these studies’ empirical foundations more credibility, guaranteeing researchers have obtained optimal results. This body of literature thus supports the validity of the present study’s approach and contribution to the existing knowledge in this field.

3.2. Sample and data

This study focused on companies in the first Spanish region (i.e., Extremadura) to approve an act promoting CSR practices (i.e., Law 15/2010 of December 9 on Corporate Social Responsibility in Extremadura). This region thus offers specific conditions regarding CSR, and Extremadura companies can formulate distinctive responses. The law defines a constructive, nonpunitive framework that gives value to these firms’ efforts to follow socially responsible strategies. In addition, at the regional, national, and international level, the government uses laws to provide companies with opportunities, allowing these firms to take on responsible roles in the market and to become examples for other companies by monitoring their own behaviors.

The data were collected with a structured Google questionnaire distributed via email to companies´ managers. The companies chosen to be part of the sample were selected taking into account that they were previously sensitized to CSR, even though they had a weak CSR strategy. This method was selected for two reasons. First, the database’s definition was conditioned because messages could only be sent to those firms that have published their address in the relevant networks and thus have greater visibility. Second, the sample could only include those companies that chose to fill out the survey.

The questionnaire was delivered between January 15th and February 15th, 2017. Emails were sent to 1,882 companies. A total of 165 questionnaires were completed, yielding a response rate of 11.41% (see Table 1). The questionnaires were sent to managers of companies sensitized to CSR issues, who showed great interest in sharing their perceptions on the topic under study. However, the answer does not always come from managers. Thus, although at first it was directed to presidents, general directors or other directors, later this possibility was opened, giving the option to have it answered by personnel who, without holding the aforementioned positions, but did know the CSR actions carried out by the company. The questionnaire was sent and collected via e-mail, with a maximum of five reminder emails sent to each company if no previous response was obtained. The answers to the initial email covered a variety of responses ranging from “thank you for including us” to “I am not interested in participating” or “my time is money, so I do nothing for free.”

Table 1. Study technical sheet

| Data sheet of sample information | |

|---|---|

| Universe of study | Extremadura companies: 65,484 companies of all sizes† |

| Geographical scope | Extremadura |

| Method of gathering information | Structured Google questionnaire sent by email |

| Number of companies to which emails were sent | 1,882 |

| Sample | 165 |

| Response collection period | Between January 15th and February 15th, 2017 |

| Participation rate | 11.41% |

| Sample error | 7.3% |

| Confidence level | 95% |

Note: † Source: Directorio Central de Empresas (2016)

Source: Authors

Among the companies that did not answer the questionnaire, the reasons included 11 companies who indicated that they could not fill in the questionnaire because they did not have a Google account. A further 6 companies reported that for various reasons they could not access the questionnaire, while 4 companies replied that they were not interested in participating and 2 companies requested more information before completing the questionnaire. Two other companies indicated that they were in bankruptcy proceedings and that they did not have the personnel needed to answer the questionnaire. One company said it had been closed down, and another company said it would not participate in the survey because no one had any idea what corporate responsibility meant. The two companies that requested further information ended up answering the questionnaire. Therefore, of the 1,717 companies that did not participate, 25 provided the reason why they did not participate, which left 1,692 companies that did not participate or acknowledge being contacted for unknown reasons.

A preliminary analysis revealed that 73.33% of the companies surveyed belong to the tertiary or services sector, 18.18% to the secondary sector, and 8.48% to the primary sector. Within the primary sector companies, 64.29% are engaged in agricultural livestock activities and 35.71% in extractive activities. Of the secondary sector firms, 46.7% belong to the food industry, while 23.3% are involved in metalworking, 20% in other manufacturing activities, and 10% in wood, cork, paper, and furniture production. Regarding the tertiary sector companies, 33.1% offer other services, 26.4% are in commerce and 17.4% in construction.

In terms of company size, most firms surveyed had between 10 and 49 employees (53.33%), followed by companies with less than 10 employees (38.79%). The remaining 8% was businesses with between 50 and 249 workers (6.06%) and companies with more than 250 workers (1.82%). With regard to the respondents’ position within their company, the majority were presidents and/or general managers (36.4%), followed by those in administrative positions (27.9%). The respondents who checked “Other” (16.4%) and thus were not administrators reported having a variety of positions. These included, among others, communication director; human resources (HR) manager; quality manager; research, development, and innovation manager; marketing technician; purchasing manager; and accountant.

3.3. Measurement scales

CSR information and CSR diffusion. The scales focused on these two constructs were based on Gallardo-Vázquez and Sánchez-Hernández's (2014b) work. CSR information was measured using 4 items and CSR diffusion with 5 items. More recently, these scales have also been used by Sánchez-Hernández et al. (2019).

CSR’s social, economic, and environmental dimensions. The scales concentrating on these three CSR dimensions were based on Gallardo-Vázquez and Sánchez-Hernández's (2014a) research. The social dimension was measured using 15 items, the economic dimension with 11 items, and the environmental dimension with 9 items. Subsequently, these scales were used in Moneva-Abadía et al. (2018) study.

Responses to all items used a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = “Strongly disagree”; 5 = “Strongly agree”). The questionnaire with all items is provided in Appendix 1, and those items that were validated in the model are marked with a superscript letter a.

4. Data analysis and results

4.1. Descriptive statistics

Table 2 shows the mean and standard deviation of all the items used to measure the model’s constructs. Regarding Extremadura companies’ CSR information, the results reveal that this is limited, which indicates the firms surveyed need to adopt new information acquisition mechanisms. The respondents gave these items mean values of 3.121, 3.000, 3.679, and 3.061 on a scale of 0 to 5. With regard to CSR’s social dimension, in general, the values are higher, ranging from 2.794 to 4.309. In this case, companies’ managers should work on strengthening their perception of the importance of having employee pension plans and encouraging employees to participate in volunteer activities or in collaboration projects with non-governmental organizations.

Table 2. Mean and standard deviation

| Construct | Item | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSR information | I1 | 3.121 | 1.094 |

| I2 | 3.000 | 1.128 | |

| I3 | 3.679 | 0.985 | |

| I4 | 3.061 | 1.099 | |

| Social dimension of CSR | SD1 | 3.284 | 0.860 |

| SD2 | 4.188 | 0.767 | |

| SD3 | 4.236 | 0.695 | |

| SD4 | 3.636 | 0.888 | |

| SD5 | 3.727 | 0.956 | |

| SD6 | 3.848 | 0.806 | |

| SD7 | 3.988 | 0.901 | |

| SD8 | 4.145 | 0.780 | |

| SD9 | 3.903 | 0.889 | |

| SD10 | 3.970 | 0.870 | |

| SD11 | 4.309 | 0.657 | |

| SD12 | 3.321 | 0.991 | |

| SD13 | 2.794 | 1.053 | |

| SD14 | 4.042 | 0.812 | |

| SD15 | 2.855 | 1.091 | |

| Economic dimension of CSR | ED1 | 4.594 | 0.631 |

| ED2 | 4.533 | 0.638 | |

| ED3 | 4.358 | 0.713 | |

| ED4 | 4.042 | 0.841 | |

| ED5 | 4.424 | 0.662 | |

| ED6 | 4.218 | 0.731 | |

| ED7 | 4.424 | 0.653 | |

| ED8 | 4.315 | 0.745 | |

| ED9 | 4.176 | 0.927 | |

| ED10 | 3.879 | 1.002 | |

| ED11 | 3.939 | 0.983 | |

| Environmental dimension of CSR | AD1 | 3.909 | 0.800 |

| AD2 | 3.745 | 0.806 | |

| AD3 | 4.188 | 0.701 | |

| AD4 | 4.145 | 0.788 | |

| AD5 | 3.473 | 1.006 | |

| AD6 | 4.042 | 0.708 | |

| AD7 | 4.418 | 0.614 | |

| AD8 | 3.836 | 0.910 | |

| AD9 | 3.867 | 0.950 | |

| CSR diffusion | D1 | 3.321 | 1.128 |

| D2 | 2.715 | 1.127 | |

| D3 | 2.988 | 1.139 | |

| D4 | 3.267 | 1.091 | |

| D5 | 2.552 | 1.228 |

Source: Authors

For CSR’s economic dimension, mean values range from 3.879 to 4.594, which indicates that managers understand the importance of implementing CSR initiatives and their financial repercussions within the company. Nonetheless, improvements need to be made to ensure effective procedures for handling complaints and more positive perceptions of firms’ financial management as deserving regional or national public support. Regarding CSR’s environmental dimension, the mean values are also good, ranging from 3.473 to 4.418. However, companies still have to give greater importance to their participation in activities related to the protection and enhancement of the natural environment and the use of consumables, goods-in-process, and/or processed goods with a low environmental impact.

Finally, with regard to CSR diffusion, the average values are again lower, ranging from 2.552 to 3.321. These results indicate companies need to disseminate information on socially responsible initiatives using all the instruments available (e.g., sustainability reports, codes of conduct, internal reports, and websites). The firms also should become active members of organizations, businesses, or professional association or discussion forums that promote the implementation of social responsibility.

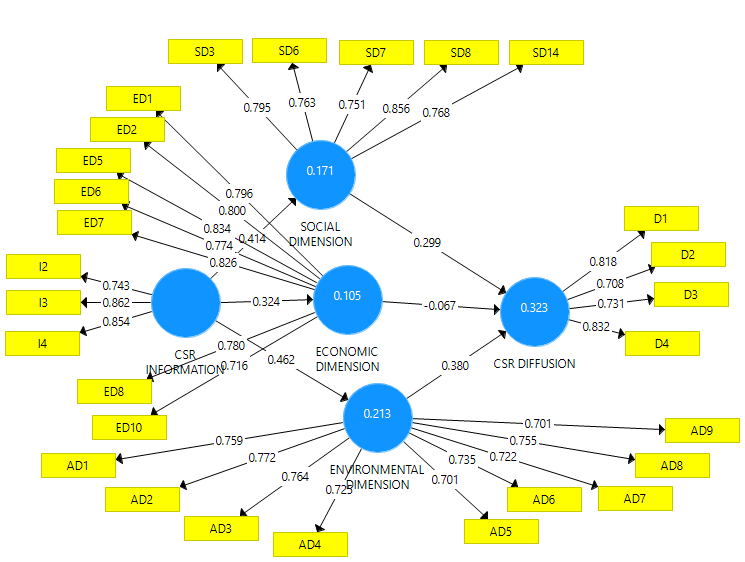

4.2. Inner model assessment

To assess the measurement instrument’s reliability, each item’s individual reliability was calculated, as well as the scales’ reliability and average variance extracted (AVE). When measuring items’ (\(\lambda\)) relationship and individual reliability, factor loadings need to be greater than 0.707 (\(\lambda\) > 0.707) (e.g., Chin & Dibbern, 2010; Roberts, Priest, & Traynor, 2006). The values obtained in the present research range from 0.701 to 0.862. Of the initial 48 items, a total of 27 indicators were retained for further analysis (see Table 3).

Table 3. Measurement model

| Construct | Indicator | Factor loading (λ) | Cronbach’s alpha | Composite reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR information | I2 | 0.743 | 0.765 | 0.861 | 0.675 |

| I3 | 0.862 | ||||

| I4 | 0.854 | ||||

| CSR diffusion | D1 | 0.818 | 0.780 | 0.856 | 0.599 |

| D2 | 0.708 | ||||

| D3 | 0.731 | ||||

| D4 | 0.832 | ||||

| Social dimension of CSR | SD3 | 0.795 | 0,846 | 0.891 | 0.620 |

| SD6 | 0.763 | ||||

| SD7 | 0.751 | ||||

| SD8 | 0.856 | ||||

| SD14 | 0.768 | ||||

| Economic dimension of CSR | ED1 | 0.796 | 0.899 | 0.921 | 0.624 |

| ED2 | 0.800 | ||||

| ED5 | 0.834 | ||||

| ED6 | 0.774 | ||||

| ED7 | 0.826 | ||||

| ED8 | 0.780 | ||||

| ED10 | 0.716 | ||||

| Environmental dimension of CSR | AD1 | 0.759 | 0.896 | 0.915 | 0.544 |

| AD2 | 0.772 | ||||

| AD3 | 0.764 | ||||

| AD4 | 0.725 | ||||

| AD5 | 0.701 | ||||

| AD6 | 0.735 | ||||

| AD7 | 0.722 | ||||

| AD8 | 0.755 | ||||

| AD9 | 0.701 |

Source: Authors

Next, the measurement model was evaluated by reviewing the instrument’s overall reliability. Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability were used since they indicate how well a set of items measures a latent variable. The Cronbach’s alpha values in the current study were also considered satisfactory because they are over 0.70 (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham, 2006), falling between 0.765 and 0.899. That is, a value of 0.765 was obtained for CSR information, 0.780 for CSR diffusion, 0.846 for CSR’s social dimension, 0.896 for the environmental dimension, and 0.899 for the economic dimension. These results confirm the scales’ high reliability (see Table 1 above).

The composite reliability analysis also produced acceptable values ranging from 0.856 to 0.921. Namely, a value of 0.856 was obtained for CSR diffusion, 0.861 for CSR information, 0.891 for CSR’s social dimension, 0.915 for the environmental dimension, and 0.921 for the economic dimension. Nunnally (1978) and Vandenberg & Lance (2000) recommend scores above 0.80 for advanced research (see Table 3 above). Therefore, the constructs’ internal consistency was confirmed.

To assess the model’s validity, the constructs’ convergent and discriminant validity were checked. Convergent validity shows the degree to which distinct approaches to construct measurement can lead to the same outcomes. This type of validity was analyzed by calculating the AVE (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hair, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2011). The AVE values range from 0.544 to 0.675. More specifically, a value of 0.544 was obtained for CSR’s environmental dimension, 0.599 for CSR diffusion, 0.620 for CSR’s social dimension, 0.624 for the economic dimension, and 0.675 for CSR information. These results are satisfactory because the values need to be higher than 0.500 (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham, 2010). Table 3 above shows that the conditions of the recommended minimum are met, so the model constructs’ convergent validity can be considered satisfactory.

Finally, the constructs’ discriminant validity reveals the existence of differences between each construct and its items with respect to the other constructs and their items. According to Fornell & Larcker's (1981) criterion, this form of validity can be verified by analyzing the square root of AVE. The values—shown in diagonal and bold in Table 4—for vertical and horizontal AVE are below the correlations between constructs (Henseler, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2015; Roldán & Sánchez-Franco, 2012) (i.e., 0.774 > 0.336, 0.526, 0.486, and 0.756; 0.790 > 0.336, 0.535, 0.664, and 0.324; 0.738 > 0.526, 0.535, 0.607, and 0.462; 0.787 > 0.486, 0.664, 0.607, and 0.414; 0.822 > 0.756, 0.324, 0.462, and 4.414). These results confirm the model’s discriminant validity.

Table 4. Constructs’ discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker’s criterion)

| Construct | CSR diffusion | Economic dimension | Environmental dimension | Social dimension | CSR information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR diffusion | 0.774 | ||||

| Economic dimension | 0.336 | 0.790 | |||

| Environmental dimension | 0.526 | 0.535 | 0.738 | ||

| Social dimension | 0.486 | 0.664 | 0.607 | 0.787 | |

| CSR information | 0.756 | 0.324 | 0.462 | 0.414 | 0.822 |

Source: Authors

Concurrently, discriminant validity was calculated based on the heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) (see Table 5). Henseler, Ringle, & Sarstedt (2015) and Roldán and Sánchez-Franco (2012) indicate a maximum threshold of 0.90 is acceptable. The values in Table 4 above are all below that value. According to this criterion, all the model’s variables also achieved discriminant validity. The results, therefore, confirm that all constructs in the present study meet the established discriminant validity criteria. The model’s nomogram could be constructed next (see Figure 2).

Table 5. Construct discriminant validity (HTMT)

| Construct | CSR diffusion | Economic dimension | Environmental dimension | Social dimension | CSR information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR diffusion | |||||

| Economic dimension | 0.374 | ||||

| Environmental dimension | 0.585 | 0.606 | |||

| Social dimension | 0.568 | 0.756 | 0.701 | ||

| CSR information | 0.581 | 0.358 | 0.536 | 0.482 |

Source: Authors

Figure 2. Explanatory nomogram

Source: Authors

4.3. Outer model assessment

The structural model was used to evaluate the weight and magnitude of the relationships between the model’s different variables taken from the research hypotheses (Wright, Campbell, Thatcher, & Robert, 2012). Thus, the model’s predictive power had to be assessed first. The predictor variables’ contribution to the explained variance of the endogenous variables was evaluated by analyzing the path coefficients (\(\beta\)) or standardized regression weights obtained. Chin (1998b) proposes that these weights need to present values exceeding 0.2 but ideally greater than 0.3. However, are less demanding, suggesting that, in empirical research, one variable has a predictive effect on another when the first variable explains at least 1.5% of the endogenous variable’s variance (see Table 6). In the present study, the \(\beta\) values were 0.299, 0.324, 0.324, 0.380, 0.414, and -0.067, with only one value not meeting Chin's (1998b) recommended minimum (i.e., H5). If Falk & Miller's (1992) criteria are applied, the variance explained can be seen to vary between 10.50%, 14.53%, 14.97%, 17.25%, and 19.99%, resulting in a value of 2.25% that, although it exceeds the recommended minimum of 1.5%, is quite low but that suggests the results do not support all the hypotheses.

Table 6. Hypotheses contrasted (correlation and variance explained)

| Hypothesis | Path coefficient (β) | P-value | Correlation | T-value (bootstrap) | Variance explained (%) | Supported (yes/no) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: CSR information → Social dimension initiatives | 0.414*** | 0.000 | 0.414 | 7.643 | 17.14% | Yes |

| H2: CSR information → Economic dimension initiatives | 0.324*** | 0.000 | 0.324 | 6.097 | 10.50% | Yes |

| H3: CSR information → Environmental dimension initiatives | 0.324*** | 0.000 | 0.462 | 7.008 | 14.97% | Yes |

| H4: Social dimension initiatives → CSR diffusion | 0.299*** | 0.001 | 0.486 | 3.716 | 14.53% | Yes |

| H5: Economic dimension initiatives → CSR diffusion | -0.067 | 0.504 | 0.336 | 0.728 | 2.25% | No |

| H6: Environmental dimension initiatives → CSR diffusion | 0.380*** | 0.000 | 0.526 | 3.295 | 19.99% | Yes |

Note: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; based on a Student’s t (4999) one-tailed distribution; t (0,05, 4999) = 1.645; t (0,01, 4999) = 2.327; t (0,001, 4999) = 3.092

Source: Authors

Analysis of the paths’ significance can also be used to verify if empirical support exists for the set of hypotheses formulated. If the path coefficients (i.e., \(\beta\)) are significant, the hypotheses are supported. To carry out this analysis, a nonparametric resampling technique (i.e., a bootstrapping procedure) was applied, which provided both the standard error and values of the Student’s t-statistic for the parameters. The analysis required a bootstrap test of 5,000 subsamples and used a Student’s t-distribution. The latter was based on a tail with n - 1 degrees of freedom, in which n is the number of subsamples (Chin, 1998a; Hair et al., 2011). The present test was conducted with the sample data, producing quite satisfactory results, although a confirmation of all the hypotheses posited in this research would have been preferable.

Table 6 reveals that all but one of the structural paths proposed in the model are significant, although with different levels of significance. Thus, 5 out of 6 of the model’s hypotheses are supported by the results. Despite the lack of a significant direct link between CSR economic initiatives with CSR diffusion (i.e., a \(\beta\) value of -0.067 and a p-value of 0.504), the other 5 relationships were validated by the data, confirming SMEs’ strong contribution to CSR. For H1, H2, H3, H4, and H6, the variables’ significant positive effects were confirmed with \(\beta\) values of 0.299, 0.324, 0.324, 0.380, and 0.414, respectively, and a p-value of less than 0.001.

The bootstrapping procedure was used to analyze the percentile confidence intervals (CI), as well as the bias corrected. These values exceed a zero value, as recommended by Chin (1998a) (see Table 7).

Table 7. Percentile CI and/or bias corrected CI

| Hypothesis | Path coefficient (β) | Percentile CI 5.0% | Percentile CI 95.0% | Bias corrected CI 5.0% | Bias corrected CI 95.0% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: CSR information → Social dimension initiatives | 0.414*** | 0.317 | 0.527 | 0.317 | 0.528 |

| H2: CSR information → Economic dimension initiatives | 0.324*** | 0.224 | 0.450 | 0.219 | 0.446 |

| H3: CSR information → Environmental dimension initiatives | 0.324*** | 0.371 | 0.575 | 0.373 | 0.578 |

| H4: Social dimension initiatives → CSR diffusion | 0.299*** | 0.130 | 0.458 | 0.125 | 0.467 |

| H5: Economic dimension initiatives → CSR diffusion | -0.067 | -0.219 | 0.105 | -0.231 | 0.103 |

| H6: Environmental dimension initiatives → CSR diffusion | 0.380*** | 0.256 | 0.532 | 0.251 | 0.534 |

Note: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; based on a Student’s t (4999) one-tailed distribution; t (0,05, 4999) = 1.645; t (0,01, 4999) = 2.327; t (0,001, 4999) = 3.092

Source: Authors

In addition, the models’ predictive power and goodness of fit were checked. According to Chin (2010), a model’s goodness of fit is determined based on each structural path’s strength and analyzed by calculating the value of R2, namely, the variance explained by the latent dependent variables. For each path or relationship between constructs, the R2 values must be at least equal to or greater than 0.1 (Falk & Miller, 1992). This condition was met, thereby confirming that the proposed and analyzed model has adequate predictive power. Table 8 shows the R2 values calculated for the dependent constructs included in the structural model. According to Falk & Miller's (1992) guidelines, all the dependent constructs should have appropriate R2 values exceeding the minimum value of 0.1.

To measure the significance of the dependent constructs’ predictive power, PLS uses Stone-Geisser’s Q2 as a criterion. This index is calculated based on the redundancies that result from the product of communalities (\(\lambda^2\)) with the AVE, which is obtained through cross-loading analysis. According to Chin (2010) and Hair et al. (2011), the Q2 value is calculated by following the blindfolding procedure, a technique that reuses the sample by omitting part of it and using the estimated result to predict the omitted part. The results need to be interpreted as follows (Chin, 2010; Hair et al., 2011). If Q2 > 0, the model has predictive capability, but, if Q2 < 0, the model has no predictive capability. This analysis’s results are presented in Table 8. Based on Chin's (1998a) recommendations, the present results can be said to confirm that the constructs’ predictive power is significant because positive Q2 values were obtained.

Regarding the model’s goodness of fit, various indices available for PLS can be used (Henseler, 2017; Henseler, Hubona & Ray, 2016). Henseler et al. (2014) developed and empirically validated a global measure that can be applied in conjunction with PLS, namely, the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). The indices d_ULS and d_G can also be utilized. Henseler et al. (2014) suggest that this measure’s value should not exceed a maximum value of 0.08.

In the present study, the SRMR was found to have a value of 0.08, so the model’s overall fit is satisfactory. In relation to the d_ULS and d_G fitness tests, values of 2.624 and 0.929, respectively, were obtained (i.e., lower than the 95% percentile), confirming that any existing discrepancy is not significant (see Table 8). Finally, the correlation value of the mean square error (i.e., RMStheta) was analyzed (Henseler, Hubona, & Ray, 2016). In the current research, this indicator achieved a value of 0.124. This indicator must be quite close to 0 and less than 0.12. The value obtained is, nonetheless, considered to be within the required margins (Henseler, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2016) (see Table 7 above). The tests carried out confirmed that the global model is a good fit for the data and well aligned with the existing theory. Table 8 lists the results of the different fitness tests.

Table 8. Predictive power and model fit

| Constructs | R2 (explained variance) | Q² (1-SSE/SSO) | SRMR | d_ULS | d_G | RMStheta |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR diffusion | 0.323 | 0.169 | 0.080 | 2.624 | 0.929 | 0.124 |

| Social dimension | 0.171 | 0.094 | ||||

| Economic dimension | 0.105 | 0.056 | ||||

| Environmental dimension | 0.213 | 0.098 |

Note: R2 = coefficient of determination; SSE/SSO: sum of squared prediction errors/sum of the squared observations

Source: Authors

5. Discussion

We consider that to carry out this research is relevant given the importance for any company of having information on the actions it undertakes. In this case, it is important that every company that implements a CSR strategy is perfectly informed of what this entails, of the advantages but also of the costs that may be incurred. Likewise, once the initiatives have been undertaken, it is essential to carry out a diffusion of the actions carried out. This contributes to improving the competitive advantage of the company while giving it legitimacy. Therefore, both the information on CSR and the disclosure made are necessary and essential aspects of CSR. This has allowed us to analyze it from the perspective of MO, linking it with the response offered by the company, following the model of Kholi & Jaworski (1990) and Slater & Narver (2000).

In the present study, the majority of the hypotheses were validated (i.e., except for H5). CSR information contributes to the development of CSR initiatives in three dimensions: social, economic, and environmental. Managers who gather CSR information can implement initiatives that benefit all stakeholders (Kiessling et al., 2016; Martínez-Martínez et al., 2017; Öberseder et al., 2011), as posited by the stakeholders theory. These managers also properly manage resources, thereby contributing to the creation of value (Asher et al., 2005) and offering appropriate responses to the globalized market to which their companies belong (Richter & Dow, 2017). When the dynamic capabilities theory is supported by information use and the generation of initiatives, firms can develop a higher level of CSR by defining and exploring opportunities for action, applying available resources, and achieving sustainable performance (Kachouie et al., 2018; Teece, 2007), as posited by dynamic capabilities theory. Therefore, the development of social and environmental initiatives leads to CSR diffusion through reports offering significant contributions to stakeholder value (Galbreath, 2009; Ramachandran, 2011).

The current findings confirm that collecting CSR information contributes to CSR initiatives and constitutes a valuable asset (Gallardo-Vázquez & Sánchez-Hernández, 2014b), including the beneficial results that this strategy produces (Duff, 2017; Ghouri et al., 2019). Concurrently, the present findings confirm that the development of social and environmental initiatives contributes positively to CSR dissemination, which agrees with numerous authors’ results (e.g., Brunton et al., 2017; Thijssens et al., 2015). This relationship can further contribute to the generation of competitive advantages (Gamerschlag et al., 2011; Siueia et al., 2019).

The paper contributes to define a possible relationship between MO and socially responsible practices, improving the emphasis on sustainability (Barone et al., 2007; Oduro & Haylemariam, 2019). This way, this new perspective offers a better and current understanding of firms’ CSR strategies (Kholi & Jaworski, 1990; Narver & Slater, 1990). We consider that the literature on MO and CSR have improved with this paper, adding to previous research (Luo & Bhattacharya, 2009). The application of the two theories considered in the theoretical framework, stakeholders and dynamic capabilities theories, make a valuable contribution, adding new empirical evidence on the applications of these theories.

6. Conclusions, limitations, and future lines of research

The present study sought to discover whether companies gather enough CSR information to facilitate the implementation of CSR initiatives. Therefore, this research had two objectives. The first was to achieve a better understanding of how companies’ CSR information influences their development of CSR initiatives based on the triple bottom line perspective. Three hypotheses were defined, which all received support. This objective’s fulfillment provided answers to the first two RQs (i.e., RQ1 and RQ2), confirming that companies collect enough CSR information to implement appropriate strategies. The information gathered allows companies to define a complete set of activities based on the triple dimension approach.

The second objective was to analyze the relationship between the development of CSR initiatives and CSR diffusion. Three further hypotheses were formulated, of which two were supported. No empirical support was found for a direct, positive relationship between the development of economic initiatives and companies’ dissemination of CSR information. This result answered the third research question (i.e., RQ3), verifying that, once companies have carried out social and environmental CSR initiatives, these firms can disseminate the relevant information to stakeholders. However, this link cannot be confirmed for companies’ implementation of economic initiatives.

Overall, the results confirm an important link exists between information, response, and diffusion, which constitutes an extension of Kholi & Jaworski (1990) and Narver and Slater's (1990) conceptualization of the MO strategy. The findings thus provide a vision of CSR in line with previous authors but also differing from their perspectives. For example, Gallardo-Vázquez & Sánchez-Hernández (2014b) only analyzed companies’ response in terms of environmental concerns. Sánchez-Hernández et al. (2019) used a smaller sample in a business context that discourages socially responsible behaviors linked to CSR legislation. The present research contributes to the literature by uniting the two cited studies’ visions, analyzing firms’ response in all three areas of the triple bottom line—economic, social, and environmental—and collecting data on companies in a region actively promulgating a CSR law.

Most organizations and SMEs are fighting to obtain more valuable information that will allow them to improve their social, economic, and environmental CSR initiatives. Thus, this study’s findings have theoretical and practical implications. First, the results contribute to CSR research’s expansion from a holistic point of view, namely, from the triple bottom line perspective. The research’s results contribute to defining the steps that companies must follow in their CSR practices, including the moment information can be gathered about these. The findings contribute to and facilitate the continuous development of different theoretical trends in analyses of CSR practices, more specifically, from a collaborative angle that considers employees, investors, customers, suppliers, and communities. This study thus confirmed the viability of extending the MO perspective to include social responsibility strategies, in conjunction with a multi-stakeholder approach.

From a practical perspective, the results have the following implications. First, SMEs need to continue any internal practices that help these firms to capture information, as well as encouraging a corporate culture that includes developing CSR initiatives that benefit all stakeholders. Second, SMEs’ managers are clearly committed to adopting CSR practices as a way to help their companies improve their internal processes and use the correct mechanisms to communicate their most beneficial social and environmental initiatives. Third, to strengthen their dissemination of economic initiatives, SMEs should adopt new forms of communication based on innovative technologies in order to improve their organizational practices.

Last, the present results contribute to developing a more interdisciplinary perspective by successfully linking MO (Kholi & Jaworski, 1990; Narver & Slater, 1990) with a sustainable perspective. Thus, the current study added to the previous work done by Gallardo-Vázquez & Sánchez-Hernández (2014b), Bello et al. (2018), Kiessling et al. (2016), and Sánchez-Hernández et al. (2019), presenting a perspective that broadens the existing research and explains how managers can control the information they have by managing, applying, and disseminating it.

Regardless of the above contributions, the present study had some limitations. The first limitation was that the answers reflected each SME leader’s subjective opinion, so the data collected may have retained their bias. The second limitation was that the variables’ measurement was dealt with through reflective models using the PLS technique based on variance. Future extensions of this research could thus benefit from including analyses based on covariance. The last limitation is that only Spanish companies already oriented toward CSR participated in the study.

Given the above results and limitations, this study’s approach may be worth developing further by including new constructs that expand the existing knowledge about this topic. Future research could also analyze the proposed model from different angles at various regional and global levels. More specifically, the present approach could be applied to examine CSR further by incorporating issues related to the circular economy and eco-innovation.

APPENDIX

Appendix 1. Items measuring model constructs

| CSR measurement scale |

|---|

| CSR information Based on Gallardo-Vázquez and Sánchez-Hernández (2014b) |

| I1: We are well informed about business initiatives related to SR. |

| I2a: If possible, we always go to meetings on sustainable development and SR. |

| I3a: We consider the time and resources we spend on SR initiatives and their disclosure vital to our success. |

| I4a: We have implemented specific initiatives to raise awareness, educate, and inform employees on SR principles and actions. |

| Social dimension Based on Gallardo-Vázquez and Sánchez-Hernández (2014a) |

| SD1: We seek to employ more people at risk of social exclusion. |

| SD2: We value disabled people’s contributions to the business world. |

| SD3a: We are aware of employees’ quality of life. |

| SD4: We pay wages above the industry average. |

| SD5: Employees’ compensation is related to their skills and results. |

| SD6a: We maintain standards of health and safety beyond the legal minimum. |

| SD7a: We are committed to job creation (e.g., fellowships and the generation of job opportunities within the firm). |

| SD8a: We seek to promote our employees’ training and development. |

| SD9: We have human resource policies in place that facilitate a balance between employees’ professional and personal lives. |

| SD10: Employees’ initiatives are extensively taken into account in management decisions. |

| SD11: Equal opportunities exist for all employees. |

| SD12: We participate in social projects that benefit the surrounding community. |

| SD13: We encourage employees to participate in volunteer activities or in collaborative projects with non-governmental organizations. |

| SD14a: We have dynamic mechanisms in place to encourage dialogues with employees. |

| SD15: Our company is aware of the importance of having employee pension plans. |

| Economic dimension Based on Gallardo-Vázquez and Sánchez-Hernández (2014a) |

| ED1a: We take particular care to offer only high-quality products and/or services to our customers. |

| >ED2a: Our products and/or services comply with national and international quality standards. |

| ED3: We distinguish ourselves from competitors by maintaining the best price levels in relation to the quality offered. |

| ED4: The guarantee offered with our products and/or services is broader than the market average. |

| ED5a: We provide our customers with accurate, complete information about our products and/or services. |

| ED6a: Respect for consumer rights is a management priority. |

| ED7a: We strive to enhance stable relationships that include collaboration with and mutual benefits for our suppliers. |

| ED8a: We understand the importance of incorporating responsible purchasing practices (i.e., we prefer responsible suppliers). |

| ED9: We foster business relationships with companies in this region. |

| ED10a: We have effective procedures for handling complaints. |

| ED11: Our economic management deserves to receive regional or national public support. |

| Environmental dimension Based on Gallardo-Vázquez and Sánchez-Hernández (2014a) |

| AD1: We have been able to minimize our environmental impacts. |

| AD2a: We use consumables, goods-in-process, and/or processed goods with a low environmental impact. |

| AD3a: We take energy savings into account when seeking to improve our level of energy efficiency. |

| AD4a: We attach high value to the introduction of alternative sources of energy. |

| AD5a: We participate in activities related to the protection and enhancement of our natural environment. |

| AD6a: We are aware of investment planning’s importance as a way to reduce firms’ environmental impacts. |

| AD7a: We are in favor of reductions in gas emissions and waste production, including recycling materials. |

| AD8a: We have a positive predisposition to the use, purchase, or production of environmentally friendly goods. |

| AD9a: We value the use of recyclable containers and packaging. |

| CSR diffusion Based on Gallardo-Vázquez and Sánchez-Hernández (2014b) |

| D1a: SR-related values are present in our firm’s vision and strategies. |

| D2a: We are active members of organizations, businesses, and professional association or discussion forums that promote the implementation of SR. |

| D3a: Our company has developed collaborative projects with other organizations to promote SR. |

| D4a: Our firm discloses information about our activities that goes beyond purely business objectives and benefits both the company and society at large. |

| D5: We are aware of the relative convenience of informing the public about our socially responsible initiatives via all the instruments available (e.g., sustainability reports, codes of conduct, internal reports, and websites). |

Note: SR = social responsibility; a indicators that were validated in the model

Source: Adapted from Gallardo-Vázquez and Sánchez-Hernández (2014a, 2014b)