Present and future of risk disclosure in Spanish non-financial listed companies

ABSTRACT

This paper researches the reasons and expected benefits of Spanish non-financial listed companies for disclosing risk information as well as the possible motivations for not doing so. It investigates the current situation of risk disclosure but also looks forward and studies what it will be like in the near future. In view of an increasingly information demanding environment, it looks for ideas for improving the risk disclosure practice.

With the objective of gathering insights from the parties involved (preparers and users of risk information) and getting an agreed view among them, we conducted a Delphi study. The group of experts was made up of twenty-two people, thirteen internal audit directors from Spanish non-financial listed companies, five financial analysts and four scholars. We ran three rounds of questions between the months of January and July of 2017.

The study concludes, among other findings, that the demand for risk disclosure will increase in coming years, that the benefits of disclosing offset any kind of associated costs, and that the policy maker should develop more legal provisions to ensure greater clarity and consistency of risk information and more comparability among companies.

Keywords: risk; disclosure; corporate governance; listed companies; Delphi.

JEL Classification: G380, G340, G180, M190, M480.

Presente y futuro de la divulgación de información sobre riesgos en las empresas españolas cotizadas no financieras

RESUMEN

Este trabajo investiga las razones y los beneficios esperados por las empresas españolas cotizadas no financieras para divulgar información sobre riesgos, así como las posibles motivaciones para no hacerlo. Investiga la situación actual de la divulgación de riesgos, pero también mira hacia adelante y estudia cómo será ésta en un futuro próximo. A la vista de un entorno cada vez más demandante de información, busca ideas que permitan mejorar esta práctica.

Con el objetivo de conseguir los puntos de vista de las partes implicadas (preparadores y usuarios de la información de riesgos) y obtener una opinión consensuada entre ellos, realizamos un estudio Delphi. El grupo de expertos estuvo formado por veintidós personas, trece directores de auditoría interna de empresas españolas cotizadas no financieras, cinco analistas financieros y cuatro académicos. Realizamos tres rondas de preguntas entre los meses de enero y julio de 2017.

El estudio concluye, entre otras cosas, que la demanda de información sobre riesgos aumentará en los próximos años, que los beneficios derivados de la divulgación compensan a las empresas de cualquier coste asociado a ella, y que el legislador debe desarrollar más disposiciones legales que aseguren mayor claridad y consistencia de la información, y mayor comparabilidad entre compañías.

Palabras clave: riesgos; divulgación; gobierno corporativo; compañías cotizadas; Delphi

Códigos JEL: G380, G340, G180, M190, M480.

1 Introduction

In recent years, most states, regulatory bodies, professional associations and interest groups have demanded more information from listed companies. After the financial scandals that took place at the beginning of this century, shareholders and investors required more transparency of corporations. All those cases were attributed to failures in corporate governance, and there was a strong movement asking for changes in the legislations to ensure that events of this kind did not happen again (Fernández de Araoz Gómez-Acebo, 2006). The Financial Stability Forum (2002), the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, 2002), the Presidency of the European Council (2002) or the United States Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs (2002), warned states of the need to improve transparency and corporate governance. At that time, the lack of risk disclosure was already a weak point of corporate financial information. This did not include the risks to which the companies were exposed, although such risks could affect their future benefits (Cabedo & Tirado, 2004). Gradually, most states developed new disclosure requirements for listed companies. The request for more information, especially in the non-financial part of the annual report, increased (Cole & Jones, 2005), and risk information was demanded not only for financial entities but also for non-financial companies (Dobler, 2008). After the Global Financial Crisis, risk management and risk disclosure practices received a strong thrust. The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, created by mandate of the Fraud Enforcement and Recovery Act (Public Law 111-21) in the United States, pointed out the deficient management of risks, especially in financial entities, as one of the main causes of the crisis. Likewise, the OECD indicated: “the process of risk management and the overall results of risk assessments should be appropriately disclosed in a transparent and understandable fashion. Disclosure of risk factors should identify those most relevant to the company’s strategy" (OECD, 2010). Because of that, and with the purpose of restoring investor confidence and providing greater shareholder protection, most countries added additional requirements for listed companies. For it, they use a combination of legal provisions, regulatory provisions and "good governance" codes based on the "comply or explain" principle (OECD, 2017). Those provisions establish the obligation to report on company exposure to certain financial risks and the mechanisms to manage them, the risks and uncertainties that the company faces, the existing risk management systems, and the assignment of risk management responsibilities within the board of directors.

In this context, a new area of research appeared in the corporate governance field: risk disclosure, which both academics and practitioners are developing. Literature reflects the existence of two main lines of work. The purpose of the first is analytical. Its aims are to assess the risk information disclosed by listed companies, analysing its quantity, quality and characteristics; to determine the factors that influence the level of disclosure; and to study the impact of such disclosure. To do this, researchers either analyse the risk information published in the annual reports of listed companies (using content analysis methods), or directly get the opinion of the parties (users and preparers of information) by means of surveys or interviews of one of both groups. The second line presents a more practical approach and develops recommendations for more effective risk disclosure.

This paper combines and enriches both lines of research. On the one hand, it researches the reasons why Spanish listed companies disclose risk information, the benefits they expect to achieve by doing so and whether there are reasons that justify not disclosing this type of information. On the other hand, it assesses the current quality of risk information provided by companies. Moreover, this work looks towards the future and anticipates how risk disclosure will evolve in coming years. The perspective of an increasingly demanding environment, the advantages that disclosure could generate for companies and the limited quality of current risk information, drove us to intensify the development of recommendations for more effective risk disclosure. This work generates useful insights for the policy maker, since it proposes some regulatory changes that would help to establish the basis for homogeneous and comparable risk disclosure among Spanish listed companies. For the regulator, since it raises the need for more monitoring of this matter. For companies, since it alerts them to future changes and the importance of boards of directors, management teams and risk management in this matter. And finally, for practitioners, since it generates some recommendations that can be part of best practices handbooks.

Another key contribution of this work is the consensus. This paper collects the opinion of the parties involved in risk disclosure and, unlike other works, we consulted three groups simultaneously: preparers of the information, users of it, and scholars. We asked them the same questions, looking for an agreed response to the issues raised. The objective was to get a convergent perspective of the matter and ensure that the developed recommendations satisfied all parties. To do this, we used the Delphi method.

The Delphi method, developed by Dalkey and Helmer in the 1950s for the Rand Corporation, is a widely used and accepted qualitative method to achieve the convergence of opinions of a group of experts (Hsu & Sandford, 2007). Based on successive rounds of questionnaires, its main characteristics are the anonymity of participants, the controlled feedback and the statistical analysis for the interpretation of results (Dalkey & Helmer, 1963). The successive iterations allow participants to reformulate their opinions based on the information received (Landeta, 2006). The anonymity reduces the influence of dominant individuals present in the group and limits the possible manipulation or coercion of the rest. The controlled feedback allows focusing on the discussion topic and avoids deviations from the initial purpose. Finally, the statistical analysis ensures that the opinions generated by all the participants are taken into account (Dalkey, 1972).

Our panel of experts consisted of twenty-two people. Thirteen internal audit directors of Spanish non-financial listed companies (four of them working in IBEX 35 entities), as preparers of information; five financial analysts from leading Spanish companies, as users of the information; and four academics, as scholars of risk disclosure. We ran three rounds of questionnaires.

Please note that, as the new regulation that emerged after the Global Financial Crisis imposed additional information requirements on the financial sector, we have restricted our work to non-financial companies.

This paper is structured as follows. The Literature section describes the main conclusions of other works that study the disclosure of risk information in companies in different parts of the world. It also includes the current Spanish legal, regulatory and good governance provisions for non-financial companies. The Methodology section briefly describes the characteristics and advantages of the qualitative methodology as well as of the Delphi method, and provides details of how we implemented it. The Results and discussion section describes the findings of our research and compares them with those of other researchers. Finally, the Conclusions and further research section summarizes conclusions and proposes further investigation.

2 Literature

2.1 Quality of the risk information provided by listed companies

Quality information is that which covers a wide spectrum of risk factors, informs of their potential impacts, especially in the future, whether positive or negative, and provides a quantitative measure of them (Beretta & Bozzolan, 2004). Based on this definition, most of the works analysed conclude that companies are far from disclosing risk information with the appropriate quality.

In relation to risk factors, most companies provide extensive risk lists, applicable to any company, making it difficult to identify the main ones (Association of Chartered Certified Accountants [ACCA], 2014; Financial Reporting Council [FRC], 2009). The risks identified are not very relevant, very few relate to growth or to the growth strategy of the company, even though this is the most significant concern of shareholders (KPMG, 2014). There is a general tendency to report financial risks more than non-financial risks. Most companies report financial risks and internal control risks, but few report business risks (Abraham & Cox, 2007; Cabedo & Tirado, 2009; Dobler, Lajili, & Zéghal, 2011; FRC, 2009; Rodríguez Domínguez & Nogera Gámez, 2014). Management mechanisms and mitigation instruments are also better described for financial risks than for non-financial (Cabedo & Tirado, 2009).

The information tends to be qualitative, with very few quantitative specifications of the probability of occurrence of a risk and its estimated impact, especially for non-financial risks (Ali, 2005; Beretta & Bozzolan, 2004; Berger & Gleißner, 2006; Cabedo & Tirado, 2009; Campbell, Chen, Dhaliwal, Lu, & Steele, 2010; Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants [CICA], 2012; Dobler et al., 2011; Graco, 2012; Hernández Madrigal, 2011; Lajili, 2009; Linsley & Shrives, 2006; Miihkinen, 2012; Oliveira, 2012; PricewaterhouseCoopers [PwC], 2014; Rodríguez Domínguez & Nogera Gámez, 2014).

In general, there are few indications about the economic impact of risk factors (KPMG, 2014; PwC, 2014) and, when they appear, they tend to be positive (Ali, 2005; ACCA, 2014; Beretta & Bozzolan, 2004; Linsley & Shrives, 2006).

There are more references to present or past events than to future ones and, in general, there is very little prospective information (Ali, 2005; Beretta & Bozzolan, 2004; Dobler et al., 2011; Graco, 2012; Oliveira, 2012; Rodríguez Domínguez & Nogera Gámez, 2014).

There are very few explanations about risk management, criteria used for risk assessment, tolerance levels, or mitigation strategies (CICA, 2012; FRC, 2009; KPMG, 2014).

In summary, the information is routine, predictable, ineffective and adds little value (PwC, 2014). Companies disclose information about their future strategies but avoid indicating their impact, not only in quantitative terms, but also in terms of the economic sign of the expected result (Beretta & Bozzolan, 2004). An idea of what might happen is given but without specifying whether the outcome will be positive or negative (Campbell et al., 2010). The level of clarity and comprehensibility of the information is very low (Linsley & Lawrence, 2007). There are many generic sentences about risk policies but the description of risks lacks coherence (Linsley & Shrives, 2006). The general tendency is to disclose incomplete information with few details (Hernández Madrigal, 2011). The information is descriptive and anecdotal, predominantly narrative and based on philosophical aspects (Hernández Madrigal, Blanco Dopico, & Aibar Guzmán, 2012). Companies disclose generic information focusing on risk management (policies, objectives, events, classification, control mechanisms, supervision), presented in a narrative way, and with few quantitative and prospective details (Hernández Madrigal, Blanco Dopico, & Aibar Guzmán, 2011). In general, the reporting framework tends to be formal but not substantial (Beretta & Bozzolan, 2004).

Considering the above, we raise the following research question:

Q1. What is the quality level of the risk information disclosed currently by Spanish non-financial listed companies?

2.2 Matters that influence risk disclosure

Companies disclose risk information fundamentally to comply with the requirements imposed by regulators and to satisfy the social demand for more transparency and corporate social responsibility. Moreover, they consider that risk disclosure is a sign of good corporate governance, which grants them social legitimacy (Hernández Madrigal et al., 2011).

However, companies have to deal with the conflict between the tendency to be positive in the annual report and the subjective and uncertain nature of risk information. An excess of information not properly explained can provide an unjustifiably negative image of the company (CICA, 2012). No one wants to give the impression that his outlook is worse than that of his competitors or to provide them with sensitive information (Abraham, Marston, & Darby, 2012; ACCA, 2014). Companies tend to limit the voluntary disclosure of any information that may have strategic value for them (Gállego Álvarez, García Sánchez, & Rodríguez Domínguez, 2008; Reverte Sánchez, 2015). They consider risk disclosure as a time consuming practice, they hesitate whether to disclose generic or specific risks and wonder how to treat commercially sensitive information, or what to do about client confidentiality (Abraham et al., 2012).

The predominance of financial risks versus non-financial risks in risk reporting is consistent with most regulatory frameworks, which, in general, are stricter with the disclosure of financial risks (Dobler et al., 2011). The bias towards the positive is explained because most managers are interested in showing their managerial skills (Ali, 2005) and only give negative information when the risk is caused by external agents outside the control of the company (Abraham et al., 2012). The lack of quantification takes place, either because companies do not have the required tools to quantify the impact of the risks, or because they prefer not to do so for fear of possible commercial consequences or legal action by shareholders (Ali, 2005; Dobler et al., 2011; Linsley & Shrives, 2006; Oliveira, 2012). Companies seem to follow the guidelines of their legal advisors instead of those of the boards of directors (ACCA, 2014; PwC, 2014). Moreover, very exhaustive information about mitigation strategies may suggest that there are no such risks, or that the likelihood of their occurrence is practically non-existent. This may become an issue if that risk materializes in the future (CICA, 2012).

In addition to the above, other factors, such as company size, risk level, quoting in international markets or type of external auditor, may influence the level of risk disclosure of listed companies. One factor frequently analysed in the literature is the composition of the board of directors. Looking for possible relationships between this and the level of risk disclosure by companies, several features are analysed, although results are not always homogeneous. Abraham and Cox (2007), Cabedo and Tirado (2009), Carmona, de Fuentes, and Ruiz (2016), Elshandidy, Fraser, and Hussainey (2013), Lajili (2009) and Oliveira (2012) find that the number of independent directors on the board influences disclosure positively, whereas Buckby, Gallery, and Ma (2015), Cordazzo, Papa, and Rossi (2017) and Hernández Madrigal (2011) do not find any sort of relationship. Buckby et al. (2015) find that the presence of a Risk Committee and the experience of the Audit Committee members exert a positive influence. Carmona et al. (2016) and Elshandidy et al. (2013) find a positive relationship with the number of independent directors in the Audit Committee, whereas Buckby et al. (2015) do not find such a relationship. Other characteristics, such as board size, gender diversity, number of meetings, number of executive and non-executive directors, director compensation and level of commitment, are analysed but with unequal conclusions.

Considering the above, we raise the following research questions:

Q2: What and who drives or curbs Spanish non-financial listed companies when disclosing risk information?

Q3: What requirements for risk disclosure can Spanish non-financial listed companies expect for the future?

2.3 Spanish regulatory provisions for risk disclosure

There are two types of obligations for Spanish non-financial listed companies. On the one hand, the mandatory provisions of the “Ley de Sociedades de Capital” (RDL 1/2010) and the “Código de Comercio”, developed by means of specific regulations; and, on the other hand, the recommendations of the “Código de buen gobierno de las sociedades cotizadas” (Comisión Nacional del Mercado de Valores [CNMV], 2015) subject to the "comply or explain" principle.

Articles 260, 262 and 540 of the “Ley de Sociedades de Capital” contain the obligations to report on risks and on the related management systems. Article 260, developed by means of Order JUS/319/2018, states the obligation to describe the risks associated to financial instruments in the annual report, providing both qualitative and quantitative information. Based on article 262, the management report must include a description of the main risks and uncertainties to which the company is exposed, and must reflect specific information related to the risks associated to financial instruments. In addition, it establishes specific requirements to large companies for reporting non-financial information (environmental, social, personnel, respect for human rights, fight against corruption and bribery) and includes the obligation to report on the related risks. Article 49 of the “Código de Comercio” includes these same requirements for the consolidated management report. As per article 540 of the “Ley de Sociedades de Capital”, Spanish companies must inform about their risk control and management systems in the corporate governance annual report (Section E. Risk control and management system), following the guidelines dictated in the Order ECC/461/2013 and detailed in the Circular 2/2018 of the CNMV. Articles 529 ter and 529 quaterdecies of the “Ley de Sociedades de Capital” refer to the responsibility of the board of directors for risk control and management function. 529 ter establishes the non-delegable responsibility of the board of directors for determining the risk management policy of the company. 529 quaterdecies states the responsibility of the Audit Committee for supervising the effectiveness of the company's internal control, internal audit and risk management systems.

On the other hand, the “Código de buen gobierno de las sociedades cotizadas” contains several recommendations related to risk disclosure. Recommendation 39 establishes that the Audit Committee members must be selected considering their accounting, auditing or risk management experience. Recommendation 45 states that the risk management policy of the company must describe the different types of risks, level of tolerance, mitigation strategies and control and management systems. Recommendation 46 develops the risk control and management function. Recommendation 53 assigns the supervision of non-financial risks to the same committee that is responsible for corporate social responsibility matters. Recommendation 54 states that the corporate social responsibility policy must include the existing mechanisms for supervising the non-financial risks of the company.

In addition, regardless of this being outside the scope of this work, article 5c of the “Ley de Auditoria de Cuentas” 22/2015 indicates that the audit report must describe the risks of material misstatements of the financial statements; a summary of the auditor's responses to such risks and, where appropriate, the essential observations derived from them.

2.4 Impact of new regulations

In Germany, the implementation of GAS 5 in 2001 improved the description of risks and their classification; however, five years later, the information remained vague and barely effective (Berger & Gleißner, 2006). In Australia, the implementation of Principle 7 of the ASX Corporate Governance Code, "Recognize and Manage Risk", in 2007, showed uneven compliance in 2010, but with a general trend of low implementation. Half of the Top 300 companies were not disclosing all their material risks, either due to the board’s ignorance or because, deliberately, they were withholding sensitive information (Buckby et al., 2015). In Spain, the publication of the “Código unificado de buen gobierno de las sociedades cotizadas” in 2006 meant a significant change in the amount of information disclosed. However, the companies just limited disclosure to the information needed to comply with the minimum requirements of the regulation, without considering the needs of the stakeholders, or even the advantages that certain disclosures could have for them (Hernández Madrigal, 2011; Hernández Madrigal et al., 2012). In Finland, the implementation of a new IFRS standard generated more risk information, a wider spectrum of risks, more qualitative data and more detail on actions taken and risk management systems, but the lack of quantitative information continued being an issue (Miihkinen, 2012). In Italy, companies opted for the slightest form of compliance, increasing the narrative but withholding all the relevant information. Before and after new rules, the only concern of companies is to defend themselves against possible lawsuits and to avoid losses in the value of the company (Graco, 2012). In Portugal, the implementation of IFRS standards did not improve the quality of risk information, characterized by the lack of comparability and of transparency (Oliveira, 2012). In the United States, the SEC's mandate to disclose the "Risk Factors" as of 2005 was positive; now the information is specific, not generic and useful for investors, although it also presents a quantification problem (Campbell et al., 2010).

Some studies suggest that the information available on risks has increased because of regulatory initiatives (Abraham et al., 2012). However, others warn that new regulations encourage attitudes of mere compliance, turning risk information into a mere bureaucratic exercise that does not provide any value (ACCA, 2014). Besides that, the requirements of governments (and professional associations) exceed what companies are willing to disclose (Hernández Madrigal et al., 2011).

2.5 Recommendations for more effective risk disclosure

Most authors agree that it is equally important to explain the risks to which the company is exposed as the mechanisms to manage them. The ACCA (2014), the Association of Insurance and Risk Managers in Industry and Commerce (AIRMIC, 2013), the CICA (2012), the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW, 2011), the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC, 2013) in its International <IR> Framework, KPMG (2014) and PwC (2013, 2014), have developed several recommendations that can be summarised as follows. Identify the most relevant risks for the company and prioritise them; evaluate their impact and apply the materiality principle. Reflect the opinion of the management team and of the board and integrate risk information in all sections of the annual report. Explain mitigation strategies and show risk management ability. Be clear and concise. Explain changes that happened during the fiscal year, inform as frequently as necessary and keep a reporting model consistent through time.

Given the above, we raise the following research question:

Q4: Which type of regulatory change would enhance the quality of risk information disclosed by Spanish non-financial listed companies?

3 Methodology

3.1 Qualitative methodology

The research methodology can be qualitative or quantitative, depending on the phenomenon being studied or the objectives to be achieved (Losada López & López-Feal Ramil, 2003). We approached this work from a qualitative perspective since it allows existing variables and relationships in complex phenomena to be discovered and helps the influence of social context and of human behaviour to be better understood (Andriopoulos & Slater, 2013; Cohen, 1999). Qualitative methods allow details of some phenomena to be obtained, such as feelings, thought processes and emotions, which are difficult to achieve by other methods (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). They are utilized to respond, not only to the "how" a phenomenon behaves, but also to the "why" it behaves like this (Losada López & López-Feal Ramil, 2003). They are especially indicated for investigations related to the inner world of people, experiences, behaviours, emotions and feelings (Hernández Sampieri, Fernández Collado, & Baptista Lucio, 2003; Strauss & Corbin, 1990), as well as to the functioning of organizations, social or cultural movements, and interactions among nations (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Likewise, they are indicated for phenomena related to opinions, beliefs, representations, motivations, intentions, symbolic contents and strategies (Verd & Lozares, 2016). On the contrary, quantitative research is indicated to study the objective and external reality, independently of the beliefs or opinions about it (Hernández Sampieri et al., 2003).

The qualitative method produces findings that cannot be achieved through statistical procedures or by other means of quantification (Strauss & Corbin, 1990), but only through intellectual efforts that rely on qualitative techniques of data collection and analysis (Mucchielli, 2001). It is about collecting the information from the words of the people, giving them an explanation and a meaning (Losada López & López-Feal Ramil, 2003), and thus understanding and interpreting the reality as it is understood by the subjects participating in the study (Flores, Gómez, & Jiménez, 1999).

Unlike quantitative methods, that use large random samples, the qualitative method uses smaller ones, but selected in such a way that they include individuals with different experiences. This allows a broader perspective of the problem to be obtained (Campoy Aranda & Gomes Araújo, 2015).

The qualitative method is dynamic, flexible and can be modified throughout the research process (Losada López & López-Feal Ramil, 2003). The initial approach does not need to be as specific as in the quantitative method and research questions can be modelled throughout the process (Hernández Sampieri et al., 2003).

Whereas the quantitative method proves theories (formulated by means of a theoretical approach) or hypotheses, the qualitative method allows researchers to develop their own ideas about the phenomenon being studied, and thus the hypotheses are obtained as a result of the study (Hernández Sampieri et al., 2003).

Campoy Aranda and Gomes Araújo (2015) also indicate that the qualitative methods are usually simple, without complicated statistical trials and with low economic cost.

3.2 Delphi Method

The Delphi method is a qualitative method oriented to achieving the convergence of opinions of a group of experts (Dalkey & Helmer, 1963). Recent applications of the Delphi method define it also as "a social research technique whose objective is to obtain the informed opinion of a group of experts" (Landeta, 2006). It is also defined as “the compilation of opinions and comments of one or several groups of people who have a close relationship to the issue, sector, technology ... object of the investigation” (Landeta, 1999). Or as “a method to structure a process of group communication that results effective when a group of individuals, as a whole, must solve a complex problem” (Linstone & Turoff, 1975). Based on successive rounds of questions, it is characterized by the anonymity of the participants, the iteration, the controlled feedback and the statistical analysis for the interpretation of results (Dalkey & Helmer, 1963; Landeta, 2006). However, the Delphi method is often questioned due to the simplicity of its statistical methods and many authors consider that its results should be interpreted with caution (Campos Climent, Melián Navarro, & Sanchís Palacio, 2014).

In our case, we chose the Delphi method from among other qualitative techniques, since the following circumstances occurred: the problem could benefit from the subjective judgments of a group of people; the people who had to contribute to the analysis of the problem did not have a history of relationship between them and might have different backgrounds and experiences; the required number of participants was greater than the number that could interact in person effectively; the time and costs required for face-to-face meetings was unacceptable; differences of opinion among the participants could be so strong, or so difficult to accept, that the process had to be arbitrated and / or anonymous; finally, the heterogeneity of the participants was a requirement to ensure the quality of the results. As per Linston and Turoff (1975), the concurrence of all these circumstances makes the Delphi method especially recommendable.

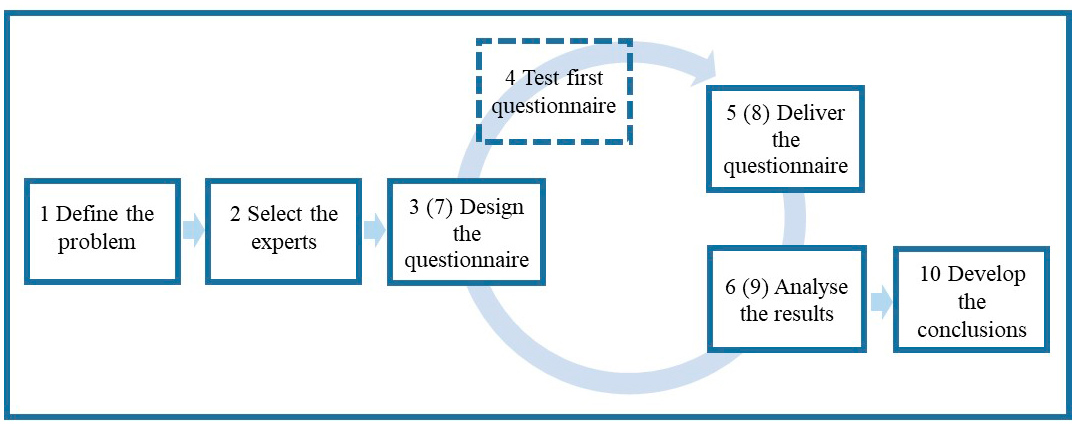

According to Landeta (1999), the Delphi method provides a flexible methodological framework that allows modifications depending on the objectives to be achieved (if the basic characteristics are maintained), and allows the researcher to act with relative autonomy. However, some basic steps are present in all studies that utilize the Delphi method. Descriptions of those steps appear in Astigarraga (2003), Campoy Aranda and Gomes Araújo (2015), Dalkey and Helmer (1963), Landeta (1999), Pill (1971) and others. We used the description provided by Ortega Mohedano (2008), which includes the steps shown in Figure 1: 1) Define the problem to address. 2) Select the group of experts that will participate in the study. 3) Design the questionnaire for the first round of questions. 4) Test the first questionnaire. 5) Deliver the questionnaire to the panellists. 6) Analyse the answers to the first round of questions 7) Prepare the second round of questions, using the results of the first one to refine the questions, whenever appropriate. 8) Deliver the second questionnaire to the panellists. 9) Analyse the answers to the second round of questions (Steps 5 to 9 must be repeated iteratively until a consensus or certain stability in the answers is reached). 10) Prepare a final report with the conclusions of the exercise. We implemented these steps as shown in the diagram below.

Figure 1: Delphi method

Source: Authors´ develpoment(2019) based on Ortega Mohedano(2008)

3.3 Select the experts

We established three starting points for selecting our panel of experts. The first was to guarantee that the participants had an adequate knowledge of the subject (Anderson, 1993; Campoy Aranda & Gomes Araújo, 2015; Cantrill, Sibbald, & Buetow, 1996; Landeta, 2006; Ortega Mohedano, 2008; Pill, 1971). The second was to ensure the variety of their experiences (Heras, Cilleruelo, & Iradi, 2008; Hsu & Sandford, 2007; Linstone, 1978; Ortega Mohedano, 2008). The third was to count on between 20 and 30 panellists (Astigarraga, 2003; Campoy Aranda & Gomes Araújo, 2015; Delbecq, Van de Ven, Andrew, & Gustafson, 1975; Malla & Zabala, 1978; Ortega Mohedano, 2008). Keeping these principles in mind, we set up a panel of 28 people who were selected as follows.

Firstly, we identified the non-financial companies listed on the Spanish Continuous Market on January 9, 2017. Then, we had to decide who would represent these companies in our study and we opted for the internal audit directors due to their knowledge of the matter (Instituto de Auditores Internos de España, 2017). Therefore, we invited the internal audit directors of ninety-three Spanish non-financial companies to participate in our Delphi study. Fourteen of them (five of whom worked in IBEX 35 companies at that time) accepted.

Secondly, we wanted to count on the opinion of users of risk information. As the behaviour of analysts may provide insights into the activities and beliefs of investors (Nichols, 1989; Schipper, 1991), and to the extent that analysts may represent or influence investors’ beliefs (Lang and Lundholm, 1996), we decided to include financial analysts in our panel of experts. Out of the ninety-three companies included in the study, thirty-six (nineteen of them belonging to the IBEX 35) publish the name of the financial analysts who regularly monitor their share value. We thus composed a list of ninety-two financial analysts and invited them to participate in our study. Nine of them, from leading Spanish companies, agreed.

Finally, during the phase of literature review of the present work, we had identified twelve Spanish risk disclosure scholars who have published articles in specialized journals and also written or directed doctoral theses, so we invited them to participate in the Delphi study. Five of them accepted and became part of our panel of experts.

However, as in most Delphi studies (Campoy Aranda & Gomes Araújo, 2015; Gupta & Clarke, 1996; Landeta, 2006; Mullen, 2003; Ortega Mohedano, 2008), there were some withdrawals during the process. The first round of the Delphi consisted of twenty-eight participants, the second one, twenty-three, and the third and final one, twenty-two people: thirteen internal audit directors, five financial analysts and four scholars.

3.4 Design the questionnaire

The design of the questionnaires followed the recommendations of the experts. The questionnaires must facilitate the response of the participants (Astigarraga, 2003; Landeta, 2006). The questions must be precise and such that they allow the answers to be quantified and weighted (Astigarraga, 2003; Ortega Mohedano, 2008) by means of quantitative criteria (Campos Climent et al., 2014). They should encourage the experts to provide qualitative comments and additional explanations (Landeta, 2006); and they must be accompanied by a cover letter (Campoy Aranda & Gomes Araújo, 2015).

The first Delphi questionnaire was prepared based on a thorough review of the existing literature, and the following ones depending on the answers obtained in the previous rounds. The issues agreed in one round did not pass to the following one, but in absence of consensus, we reformulated the question and included it in the questionnaire of the following round, together with new issues raised by the participants. Given that the Delphi method allows the researcher to define the acceptable level of consensus (Landeta, 1999), we set it at 70%.

3.5 Test first questionnaire

Additionally, as Landeta (2006), Mucchielli (2001) and Ortega Mohedano (2008) recommend, a small group of experts reviewed the questionnaire for the first round in advance. This group was made up of the Business Risks Director of an IBEX 35 company belonging to the Basic Materials, Industry and Construction sector; the Internal Audit Director of a company in the Technology and Telecommunications sector; and a Fund Manager of a financial entity.

3.6 Deliver the questionnaire

Lately, most Delphi processes are carried out electronically because of the multiple advantages of this approach (Díaz de Rada, 2012; Fox, Murray, & Warm, 2003; Ilieva, Baron, & Healey, 2002; Wright, 2005). Until a few years ago, the development of online surveys was a complicated task that required specific programming skills. However, today there are software packages and web applications that have solved this problem. We opted for one of these platforms, which is called EncuestaFácil.com.

3.7 Analyse the results

The present Delphi took place in three rounds between the months of January and July of 2017. As experts recommend, the analysis of results was carried out in two stages. First, we collected the data of the structured parts of the questionnaires, ordered them and distributed the frequencies of the answers. Secondly, we integrated the quantitative and qualitative responses of the participants with our own perception (Landeta, 1999; Losada López & López-Feal Ramil, 2003; Patton, 1987) and generated the results of the study.

4 Results and discussion

The usefulness of risk information is sometimes questioned because it is intrinsically subjective and it is not possible to verify or audit it (ICAEW, 2011). However, our group of experts consider it very important that companies report on the risks to which they are exposed and on the systems that they have to control and manage them.

Understandably, if companies do not see a clear benefit from the disclosure of risks, or if the benefit is lower than the cost of such disclosure, they will just comply with the regulatory requirements at a minimum level (ICAEW, 2011). According to Hernández Madrigal et al. (2011), compliance with regulations is the first reason given by Spanish listed companies for disclosing information, while satisfying the social demands of transparency and corporate social responsibility is the second one. However, our group of experts sets mere compliance in fourth place and considers that demonstrating the company’s commitment to transparency and good corporate governance is the first. They consider that satisfying the information needs of the capital providers is the second reason. Moreover, they identify others in the following order of importance: satisfy the information needs of the stakeholders; comply with the requirements of the regulator; demonstrate management ability to accomplish the company's business plan; avoid possible future lawsuits for concealing information; be a leader in disclosure; emulate competitors and, finally, justify possible bad results.

Our panellists consider that risk disclosure is beneficial for the company. Firstly, because the company increases its social legitimacy by satisfying the requirements of transparency and good governance required by society. Secondly, because it builds trust among investors, as uncertainty about the future performance of the company decreases. Besides that, our experts identify other benefits of risk disclosure, ordering them by importance in the following sequence: improve the relationship between the company and its stakeholders; allow investors to get better knowledge of the management of the company; demonstrate the effectiveness of a robust risk and opportunity management system; increase the company's access to the capital market, increase the liquidity of the shares and reduce the cost of capital; generate greater consensus among financial analysts, increasing investor confidence and, finally, increase the value of the company by demonstrating that the risks do not materialise.

These results are in line with most theories of corporate information disclosure. The theory of Legitimacy states that companies need to permanently reconfirm their legitimacy by demonstrating to society that it needs their services, and that the groups that benefit from their activity are socially accepted (Shocker & Sethi, 1973). Therefore, companies use communication, symbolic actions and transparency to show a suitable public image (Cormier & Gordon, 2001; Dowling & Pfeffer, 1975). According to Signalling theory (Spence, 1973), companies that consider themselves better than the rest, highlight it by disclosing more information than what is strictly necessary and thus improve their reputation and attract investorsʼ interest (Campbell, Shrives, & Bohmbach-Saager, 2001). Stakeholdersʼ theory (Freeman, 1984) considers it essential to take into account the relationships between the company and the groups or individuals which it affects, and numerous studies find several links between the disclosure of voluntary information and the demands of stakeholders (Parmar et al., 2010). In an agency relationship (Ross, 1973), the agency costs, materialised in form of performance bonus or incentives for the management teams, ensure that the agent makes the best decisions for the principal (Jensen & Meckling, 1976). Information disclosure reduces these costs by ensuring that the actions of the management teams are well visible and can be controlled by the shareholders (Gallego Álvarez et al., 2008; Reverte Sánchez, 2015). In addition, companies that are able to reduce the asymmetry of information generate the confidence of investors, who will interpret that the purchase of shares is done at a fair price. This will increase the liquidity of the shares (Diamond & Verrecchia, 1991). Moreover, given that a part of the cost of capital corresponds to the uncertainties of the corporate information, reducing this uncertainty will also reduce the cost of capital (Financial Accounting Standards Board [FASB], 2001). Lang and Lundholm (1996) find that companies with a solid disclosure regime have greater monitoring from analysts and generate greater consensus among them. This suggests that they will potentially have more investors, who will have fewer doubts about the future performance of the company. Besides that, the need for capital is one of the main reasons for corporate information disclosure, and companies compete for capital. Therefore, when in order to satisfy the demands of investors, one company begins to report on a certain matter, the rest follow suit and also start to report on that matter (FASB, 2001). Moreover, not doing so will be seen as a sign of concealing information (Lopes & Rodrigues, 2007).

Despite the opinions gathered in other works (Abraham et al., 2012; ACCA, 2014; CICA, 2012; ICAEW, 2011), our group of experts confirms that risk disclosure is not a mere bureaucratic exercise but adds value. It does not jeopardize the value of the company nor project a negative image. It does not weaken the competitive position of the company nor the negotiating position with customers, suppliers or employees. It is not an expensive exercise, since, although the initial costs of preparing information are high, they decrease in subsequent years, and in any case, the benefits obtained offset such costs. All this clashes with the theory of the Proprietary Costs, which states that the disclosure of any information, either favourable or unfavourable, that is useful for competitors, employees, or any other group, will have a cost for the company (Verrecchia, 1983). Based on this theory, companies will tend to limit the voluntary disclosure of any information that may have strategic value for them (Gállego Álvarez et al., 2008; Reverte Sánchez, 2015).

However, like Graham, Harvey, & Rajgopal (2005), our group of experts considers that the disclosure of information establishes a precedent, and in accordance with Campbell et al. (2001), they think that a subsequent decrease in the quality or quantity of information provided will look negative. Similarly to Skinner (1994) and Healy and Palepu (2001), our panellists consider that the materialization of unanticipated risks, or the failure of the mitigation strategies, may be attributed to the lack of ability of the management teams, and may jeopardize their credibility, and potentially their continuity.

Nevertheless, despite the benefits expected from a good risk disclosure practice, our panellists coincide with the conclusions of other works, Cabedo and Tirado (2009), Hernández Madrigal (2011), Rodríguez Domínguez and Nogera Gámez (2014), and consider that the quality of the risk information provided by Spanish listed companies is only at a medium or low level. The quantity and quality of information on financial and non-financial risks is unbalanced, and they request more information on non-financial risks, on the prioritization of risks, probability of occurrence and potential economic impact.

However, this situation will have to change in the near term. The demand for corporate information has increased in recent years, and although it emerged as an antidote against corruption (Lizcano Alvarez, 2013), the phenomenon of globalization, the internalization of capital markets, the development of information technologies (Comisión Aldama, 2003), and the increasing complexity of organizations, strategies and operations (Rodríguez Domínguez & Nogera Gámez, 2014) have been its main drivers. In this regard, our group of experts considers that risk disclosure is at an early stage and that in the coming years it will undergo important changes due to said general demand for more information. These changes will take place in two to five years, most likely because of the implementation of an international or European regulation requested by international market agents.

Provided that the competitive advantage of companies resides in their capacity to leverage new opportunities by means of careful management of the risks taken (Bromiley, McShane, Nair, & Rustambekov, 2014), our group of experts considers that reporting on the ability to manage risks is more important than to do so on the risks themselves. Therefore, the spotlight of the information will move from the risks to the risk management systems.

Abraham et al. (2012), Hernández Madrigal et al. (2011) and PwC (2016) identify shareholders, financial analysts and investors as the main users of risk information, but they also mention customers, corporate governance rating agencies and social and environmental organizations. In this regard, our group of experts considers that, in the future, not reporting risks properly will affect analysts’ recommendations and credit position. There will be more questions about risks in the meetings between analysts and management teams. Proxy advisors will include risk disclosure level in their guidelines for voting recommendations. The quality of risk information will be a factor when considering sustainable investments (Environment, Social and Governance). But customers and suppliers are not expected to request risk information to make decisions to award or participate in contract tenders.

In relation to the degree of preparation of companies for this new scenario, our experts agree that it is not realistic to expect the same level of compliance among companies with high visibility and availability of resources, and small ones with more limited resources. The theories of corporate information disclosure explain this. Based on the theory of Stakeholders, the larger the company, the more stakeholders have to be informed, the information required is more diverse and the level of information of the company has to increase (Rodríguez Domínguez & Noguera Gámez, 2014). Large companies generally have a large part of their assets financed with debt, so they must be more transparent in order to meet the information needs of their creditors (Jensen & Meckling, 1976). Likewise, the disclosure of information requires counting on qualified personnel that normally only large companies are able to employ (Cooke, 1989). They also have greater exposure to political costs, so they are more sensitive to regulatory requirements, including those related to disclosure of information (Watts & Zimmerman, 1978). Large companies have more resources to generate information, and the cost for them is usually relatively lower than for small companies; in addition, the latter tend to be more sensitive to the disadvantages that information disclosure could bring. (Cordazzo et al., 2017; Elshandidy et al., 2013). According to the Signalling theory, large companies will try to show that they are better than others are by disclosing more information than what is strictly necessary (Campbell et al., 2001). Besides that, in accordance with Agency theory, they need to disclose more information to reduce information asymmetry and agency costs (Watts & Zimmerman, 1983).

The described outlook makes certain changes necessary. Our group of experts consider unanimously that the provisions included in Spanish legislation, or dictated by the CNMV, are insufficient, especially those related to strategic and operational risks. They also consider that the current format and requirements of section "E. Risk control and management systems" of the corporate governance annual report are insufficient and do not provide an adequate view of the company’s risk management system.

Therefore, they recommend a change in regulation. Although the issuance of new regulations does not always entail a clear enhancement of the disclosure level (Berger & Gleißner, 2006; Buckby et al., 2015; Graco, 2012; Hernández Madrigal, 2011; Miihkinen, 2012; Oliveira, 2012), our group of experts considers that the Spanish regulator should develop provisions for greater clarity and consistency of information among companies. The panellists agree that the regulator should initially develop these guidelines as recommendations of the “Código de buen gobierno de las sociedades cotizadas”, and incorporate them into the legislation later on, as has happened with other recommendations of prior codes (Olivencia, Aldama and “Código unificado de buen gobierno de las sociedades cotizadas”).

However, similarly to ACCA (2014), they also mention that an excess of regulation could encourage attitudes of mere compliance, reducing disclosure to a bureaucratic exercise and depriving it of all interest. In any case, our group of panellists agree on the following possible provisions.

There should be a reference framework for risk management systems. It could be Enterprise Risk Management – Integrated Framework (2004) or Enterprise Risk Management – Integrating with Strategy and Performance (2017), developed by the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission [COSO]. The standard ISO 31000:2009 could also be useful. Risk Management Standard, developed in 2002 by the three British risk management associations: the Institute of Risk Management [IRM], the Association of Insurance and Risk Managers in Industry and Commerce [AIRMIC] and ALARM (National Forum for Risk Management in the Public Sector), and adopted by the Federation of European Risk Management Associations [FERMA], could serve too. In any case, companies should have at their disposal a guideline that indicates what matters to disclose, and that sets the basis for homogeneous and comparable disclosure among companies. In addition, our panellists consider that the certification of the risk management systems, based on an official standard, could improve the quality of the information disclosed. However, they also warn of the risk that the ultimate goal of certification is the certification itself instead of proper use of the system.

Spanish listed companies should describe appropriately the key elements of their risk management system. Our panellists consider that these element are, by order of importance: 1) the general policy of risk management of the company; 2) the bodies responsible for the supervision of the risk management system; 3) the mechanisms for controlling and handling each type of risk; 4) the criteria to evaluate the importance of each type of risk; 5) the new risks that have appeared during the year and how they have been incorporated into the management system; 6) the types of risks included in the system; 7) the scope of the risk management system; and, finally, 8) other specific policies for risk management. However, current Section E – Risk control and management systems of the corporate governance annual report, only requests information about: the scope of the risk management system, the bodies responsible for its supervision, the main risks that might affect achievement of the company’s objectives, whether the company has a risk tolerance level, the response and supervision plan for the main risks, and the risks materialized during the fiscal year.

With the goal of making information disclosed clear, homogeneous and comparable among companies, our group of experts consider that the regulator should provide a guide for risk classification, and all companies should use it when categorizing and describing their risks. Currently, Spanish companies only have at their disposal the “Guía para la elaboración del informe de gestión de las entidades cotizadas” (CNMV, 2013) but it is not mandatory.

The policy maker should also establish specific provisions that include the obligation to report on different types of risks, and not only on financial risks. Currently, the provisions included in article 49 of the “Código de Comercio” and in article 262 of the “Ley de Sociedades de Capital”, refer only to environmental, social, personnel, respect for human rights, fight against corruption and bribery matters. A broader view of non-financial risks (operational, technological, social, environmental, political and reputational) appears only in recommendations 45 and 53 of the “Código de buen gobierno de las sociedades cotizadas”, and in the “Guía para la elaboración del informe de gestión de las entidades cotizadas” (CNMV, 2013).

The policy maker should develop a provision whereby the companies should report on the following issues: 1) specific risks of the company, relevant at present and in the near future; 2) prioritization of the main risks, explaining the reasons for such prioritization; 3) control and treatment mechanisms for the main risks; 4) mitigation strategies in case of materialization of the main risks; 5) probability of occurrence of the main risks described; 6) potential economic impact of the main risks; 7) level of risk accepted. Additionally, disclosure of the economic impact and the mitigation mechanisms applied to the risks materialized in the fiscal year should be mandatory.

These recommendations are in line with the Beretta and Bozzolan (2004) definition of quality information, as well as with the recommendations for more efficient risk disclosure developed in other works (ACCA, 2014; AIRMIC, 2013; CICA, 2012; ICAEW, 2011; IIRC, 2013; KPMG, 2014; PwC (2013, 2014)). Current Section E of the corporate governance annual report, and the requirements for financial risks in the annual report and in the management report, partially cover these recommendations. However, the prioritization of risks, probability of occurrence and impact, especially for non-financial risks, are not required in any of the three mandatory reports.

An entire view of the risks of the company is important; therefore, all risks, regardless of their type, should appear in the same report. In this regard, we also analysed the possibility of having a new report solely for risk information. Our group of experts assessed this recommendation positively, but the level of consensus was insufficient. However, this recommendation clashes with the opinion of other authors. For CICA (2012), risks should not be explained in isolation. Although most legislations establish a specific section for risks in annual reports, the information must be integrated in all sections. Risks affect many aspects of a company's operations; therefore, they cannot be ignored or relegated to a single section. For ICAEW (2011), the risk information must accompany especially the information related to the business model, and to all types of prospective information concerning plans, expected results and future expectations.

Apart from the changes in legislation, we discussed with our experts who could drive the required changes. They consider that the three elements that most influence the risk disclosure framework of listed companies are, in order of importance: the commitment of the board of directors; the commitment of the management team; and to have a specific risk management function within the organization. Additionally, they consider the following important: pressure from institutional investors; being quoted on international markets; CNMV control, through its review of compliance with the recommendations of the Code of Good Governance; accounting, auditing or risk management skills of the Audit Committee members; pressure from proxy advisors; pressure from external auditor; pressure from financial analysts; and, finally, the sector in which the company operates (apart from the financial sector).

Other authors also point out the importance of the board of directors, management teams and risk managers commitment in risk disclosure, because users of information want to know their views and concerns (ACCA, 2014; PwC, 2014).

Gul and Leung (2004) indicate that corporate disclosure policy emanates from the board, and Abraham and Cox (2007) remark that, as the board prepares the annual report, its governance arrangements can be expected to influence disclosure policy. Our group of experts agrees that, in general, the members of the Audit Committee of the board of directors of Spanish companies have an adequate level of commitment with risk disclosure, but not so the rest of the directors. This can be explained because companies follow Recommendation 39 of the “Código de buen gobierno de las sociedades cotizadas” and Audit Committee members have accounting, auditing or risk management experience. Moreover, the “Ley de Sociedades de Capital” states that the Audit Committee is responsible for supervising the effectiveness of internal control, internal audit and risk management systems in the company.

In this regard, our group of experts considers that assigning the supervision of each type of risks to one or another committee of the board can make a difference in the level of disclosure of the company. Interestingly, whereas Recommendations 53 and 54 of the current “Código de buen gobierno de las sociedades cotizadas” places the supervision of non-financial risks under the scope of corporate social responsibility, our panel of experts recommends that one single board committee, preferably the Audit Committee, is responsible for supervising all type of risks.

As mentioned before, management teams have a fundamental role in risk disclosure. Boards of directors and investors consider management teams responsible for the value of the company. The undervaluing of the company can endanger the continuity of the manager, either because the company is taken over, given its low price, or as a punishment for mismanagement. Therefore, the management teams use voluntary disclosure of information to avoid underestimation, as well as to justify poor results (Healy & Palepu, 2001). In addition, stock-based compensation systems mean managers have a personal interest in increasing the liquidity and value of shares, so CEOs tend to disclose information in a way that maximizes their compensation in stock options (Aboody & Kasznik, 2000). Managers tend to report bad news quickly. If shareholders are surprised with an unexpected fall in the stock price due to poor results, they will blame managers for not having communicated this on time. Managers will then be exposed to possible legal suits and will lose the confidence of the market and financial analysts (Skinner, 1994). On the other hand, the market value of a company depends on how investors perceive the ability of managers to anticipate future changes in the economic environment and to adjust their plans accordingly. Therefore, the management teams will inform of these circumstances to demonstrate that they have the information and the ability to obtain it (Trueman, 1986). Besides that, managers explain risk causes and describe how they are managing them to demonstrate their managerial skills (Linsley & Shrives, 2006). However, the management teams will also avoid disclosing prospective information; an error in forecasts can be interpreted as a malicious manipulation instead of as a simple error, and consequently, attract unwanted legal consequences (Healy & Palepu, 2001).

In the case of Spanish management teams, our group of experts considers that their current commitment with risk disclosure is insufficient and difficult to achieve. Our experts provide some suggestions. For instance, that the regulatory requirements affect not only the members of boards of directors, but also management teams; or, that public contracting includes requirements for this type of information. However, the consensus was not sufficient.

Our group of experts places the risk control and management function as the third element that most influences risk disclosure. This function appeared in the mid-1990s as a new concept of corporate risk management, and is now an integral component of business management (Dickinson, 2001; Shenkir & Walker, 2011). The function of risk management changed from being dispersed in various peripheral functions to being placed at the corporate level, with a comprehensive view of all company risks. Although this function exists in most Spanish companies (following Recommedation 46 of the “Código de buen gobierno de las sociedades cotizadas”), our panellists consider that it is nominal in many of them and there is still a long way to go.

Additionally, our group of experts consider that the CNMV, despite the lack of clear and comprehensive guidelines on this matter, could be more demanding and should review the information provided, requesting additional details via "Specific information requirements" if needed. The panellists also recommend that the regulator controls the level of compliance of companies in this matter, and that it includes its findings and assessment in its annual corporate governance report, as it does now for other corporate governance matters.

Currently, it is considered beneficial that the external auditors audit the Internal Control System over Financial Reporting of companies (CNMV, 2010), and that they review the management reports and their conformity to regulation (Article 5f of “Ley de Auditoria de Cuentas”). Therefore, we decided to discuss with our panellists what the role of the external auditor should be in reviewing the risk control and management systems of companies, and with compliance to risk disclosure regulatory provisions. However, they did not reach a sufficient consensus. The possibility that the external auditor audits the risk management system is accepted, but only if there is an official standard or reference framework, and even in this case, the scope of the review is not clear. Likewise, some kind of external audit of the risk information is valued, but there is no agreement on whether, in addition to verifying that the mandatory reports contain the required risk information, the auditor should make some kind of assessment of such information.

5 Conclusions and further research

This document researches the reasons of Spanish non-financial listed companies for disclosing or not disclosing risk information, and identifies the expected benefits of such disclosure. It also investigates the current situation of risk disclosure within this group and develops recommendations for the policy maker, companies and the regulator, so that growing future information needs can be met. For it, we conducted qualitative research using the Delphi method. We counted on a panel of experts made up of twenty-two people, thirteen internal audit directors of Spanish non-financial listed companies, five financial analysts and four scholars. They answered three rounds of questions and the level of consensus reached in the answers was 70%.

The panel of experts considers, unanimously, that it is important that Spanish non-financial listed companies disclose information about the risks that they face and about the systems that they have to control and manage them. The main reason for doing so is to demonstrate the company's commitment to transparency and good corporate governance, thereby legitimizing the company before a society that currently demands these values. Our group of experts considers that risk disclosure does not jeopardize the value of the company nor project a negative image of it. Likewise, it does not weaken its competitive position nor the negotiating position with customers, suppliers or employees. Asked about the current quality of the information provided by companies, the opinion of our panel of experts coincides with the results of other works, and there is a generalized demand for more information about the prioritization of risks, the probability of occurrence, or the potential economic impact of the risks.

Our group of experts foresees that the demand for risk information will increase in coming years and considers that a change in legislation is necessary. They consider that the current lack of clear guidelines limits the quality and quantity of the information provided. They are practically unanimous in considering that the current provisions in Spanish legislation, or dictated by the CNMV, are insufficient. Likewise, they state that the current format of section "E. Risk control and management systems" of the corporate governance annual report does not provide an adequate understanding of the risk management system of a company.

Therefore, they consider that the policy maker should develop provisions that ensure greater clarity and consistency of risk information. These provisions should compel reporting on all types of risks and not just on financial ones, should impose description of the most relevant aspects of risk management systems, and specify the prioritization, probability, impact and mitigation strategies of the different risks. In addition, the regulator should provide Spanish companies with a reference framework for risk management systems and with a guide for risk classification that all companies should use when categorizing and describing their risks. Companies would thus have clear guidelines about what should be disclosed, and the basis for homogeneous and comparable disclosure among companies would be established.

As per our experts, the commitment of the board of directors and management teams are the factors that most influence the disclosure level of companies. They agree that the members of the Audit Committee of the board of directors have an adequate level of commitment to this issue, but not thus other board members or management teams. The group of experts considers that assigning the supervision of each type of risks to one or another committee of the board of directors can make a difference in the level of disclosure of the company, and recommends that one single committee of the board, preferably the Audit Committee, is responsible for supervising all type of risks. Besides that, they highlight the importance of the risk control and management function and advise that it still needs further development in medium and small organizations. In addition, the panellists recommend that the regulator controls the compliance of each company in this matter and that it includes the findings and assessment in its annual corporate governance report.

From a theoretical point of view, this study contributes to the literature by compiling both the reasons for Spanish listed companies to disclose risk information and the possible benefits expected from such disclosure. Besides that, it ranks them by order of importance, thus making it possible to distinguish the most relevant. It also provides certain arguments against risk disclosure while refuting others identified by other authors.

This work also has important practical implications. On the one hand, it is useful for the policy maker since it proposes some regulatory changes that would help to meet the growing demand for risk information, and that would establish the basis for homogeneous and comparable risk disclosure among Spanish listed companies. It brings to light the need for companies to have clear and precise instructions on what issues to disclose, and to have reference models available for this purpose. Likewise, it urges the regulator (CNMV) to take a more active role in monitoring the compliance of companies with current and future requirements. On the other hand, it warns companies about a future increase in the demand for risk information, and it anticipates how this will affect their relationship with the users of such information. It reminds them of the importance of the board of directors and management teams in this matter, and of the need to have a truly effective risk control and management function. In addition, it provides interesting details for practitioners. It identifies the main elements of the risk control and management systems that should be disclosed and the contents of the risk information, thus contributing to the development of best practices guides and handbooks.

This work presents certain limitations. In addition to those related to the criticisms of the Delphi method, it must be taken into account that our study gathers the opinion of the internal audit directors as representatives of the opinion of Spanish listed companies. Due to the nature of their responsibilities, it is conceivable that this group is especially sensitive to the matter, and therefore their opinions do not represent the rest of the management team. As we have seen, the level of commitment of management teams and of the board of directors are the most determining factors of the disclosure level of the company, and their attitude has a decisive influence on the quality and quantity of the information provided. For all these reasons, we consider it important to know the specific opinion of these groups, and we see that a future line of research should focus on gathering the opinions of the C-Levels and board members of Spanish non-financial listed companies. A better understanding of their perspective is essential to develop measures that increase their level of commitment, and therefore the quality of the risk information of Spanish non-financial listed companies.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest: None

Annexes

Annex I: Questionnaire round one (only available in Spanish)

Annex II: Questionnaire round two (only available in Spanish)

Annex III: Questionnaire round three (only available in Spanish)

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.