Family Budgets and Standards of Living in a Port City of Northern Spain: A Coruña, 1924

Luisa Muñoz-Abeledo, University of Santiago de Compostela

Abstract

The main goal of this article it to determine the reach of men’s wages within the purchasing power of working and fishing families in Galicia’s principal port city, A Coruña. I look at which occupations provided fathers, heads of the household, with sufficient income for the reproduction of the family unit, what the contributions of wives to the family income were, and whether or not wives’ contributions were essential for family subsistence. Through the reconstruction of family budgets, I establish, in short, whether the “male breadwinner model” was prevalent in A Coruña during the mid-1920s. I look at the main occupations of this urban economy, which, even in the first decades of the 20th century, was an important commercial and fishing center, second only to Vigo in the region.

Keywords: Household budgets, living standards, municipal population registers, A Coruña, port city

Presupuestos familiares y niveles de vida en una ciudad portuaria del norte de España: A Coruña, 1924

Resumen

El objetivo principal de este artículo es determinar la incidencia del salario masculino en el poder adquisitivo de las familias obreras y pescadoras de la principal ciudad portuaria de Galicia, A Coruña. En el mismo se analiza qué ocupaciones proporcionaban a los padres, cabezas de casa, con unos ingresos suficientes para la reproducción de la unidad familiar, cuál era la contribución de las esposas a los ingresos familiares y si la contribución de las esposas era o no esencial para la subsistencia familiar. A través de la reconstrucción de los presupuestos familiares, establezco, en definitiva, si el “modelo del varón ganador de pan” prevalecía en A Coruña a mediados de la década de 1920. Analizo las principales ocupaciones de esta economía urbana que, incluso en las primeras décadas del siglo XX, fue un importante centro comercial y pesquero, sólo superado por Vigo en la región.

Palabras clave: Presupuestos familiares, niveles de vida, padrones de población, A Coruña, ciudad portuaria

Original reception date: November 20, 2024; final version: December 23, 2024.

Luisa Muñoz-Abeledo, University of Santiago de Compostela. E-mail: luisamaria.munoz@usc.es; ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7970-3045

Family Budgets and Standards of Living in a Port City of Northern Spain: A Coruña, 1924

Luisa Muñoz-Abeledo, University of Santiago de Compostela

1. Introduction

The main goal of this article it to determine the reach of men’s wages within the purchasing power of working and fishing families in Galicia’s principal port city. I look at which occupations provided fathers with sufficient income for the reproduction of the family unit, what the contributions of wives were, and whether or not wives’ contributions were essential for family subsistence. Through the reconstruction of family budgets, I establish, in short, whether the “male breadwinner model” was prevalent in A Coruña during the mid-1920s. In earlier articles, colleagues and I have calculated labour force participation rates for rural and urban Galicia in the mid-19th and early 20th centuries (Muñoz-Abeledo et al., 2015, 2019). Also, by looking at business records and other statistical sources, we have corrected the undercounting of the primary and secondary sectors found in municipal enumerator books (Muñoz- Abeledo y Verdugo Matés, 2023). Our results revealed high participation rates, especially in industrial municipalities. We have also previously carried out research on family budgets, research that calls into question the spread of the male breadwinner model at the sector level (specifically, in textiles and food preservation) in Catalonia and Galicia (Borderías y Muñoz-Abeledo, ٢٠١٨). Nor was the model widespread in the capitals of Spanish provinces in the early 19th century (Borderías, Muñoz-Abeledo y Cussó, 2022).

Picking up the topic of family budgets again, in this article I take a “micro-historical perspective” to reconstruct standards of living for workers’ families in A Coruña in order to determine whether women’s income was necessary to cover potential deficits. I look at the main occupations of this urban economy, which, even in the first decades of the 20th century, was an important commercial and fishing center, second only to Vigo in the region. Critically, A Coruña’s industrial activity provided job opportunities in tobacco and clothes-making to many women, while domestic service remained women’s main economic activity. Although neither the census of 1920 nor the enumerator book of 1924 recorded the activity of all women, after correcting the figures of the latter for certain occupations in the secondary and tertiary sectors, colleagues and I have found that women’s participation rate was about 33 percent (Muñoz-Abeledo, Verdugo Matés y Taboada Mella, 2019).

In the first section of this article, I explain my methodology and sources. In the second, I examine how labour markets worked in early 20th-century A Coruña, including their occupational structure from a gender perspective, while identifying the main jobs for men and women. The third section reconstructs family incomes in the 1920s for different occupations, focusing on nuclear 3b families. In the fourth section, I enumerate the principal expense items so that, in the fifth, I can present family budgets for occupational groups, along with their deficits and surpluses.

2. Methodology and Sources

My main source is the municipal enumerator book (padrón) of 1924—unique for its wage information—which I use to reconstruct incomes for families whose heads worked in those occupations where most adult employment was concentrated. This source is generally available for all Spanish municipalities. It gathers detailed sociodemographic information for families, including members’ occupations, which allow participation rates to be calculated while taking account of different variables (for example, age, civil status, number of children). These rates were presented in an earlier article (Muñoz-Abeledo. Verdugo Matés y Taboada Mella, 2019)1. The 1924 enumerator book also includes wage data for family members, most notably for household heads, which allow me to investigate whether or not married women’s economic activity and their husbands’ wages were necessary to cover family expenses.

From the 66,720 (N) persons recorded in A Coruña in 1924, I constructed a random sample of 6,672 (n) individuals. To select residents from each of the city’s five districts, I used a random sample proportional to the number of pages in each of the five volumes of the enumerator book (one for each district). The initial page of each volume’s sample was randomly selected2. The resulting sample (6,672 people) represents 1,531 households.

Starting with this population sample, I reconstruct the budgets of Laslett’s 3b families. I consider families whose household heads declared income and whose wives, occupied in the same sector, also declared income. In some cases, such as agricultural families, women did not declare income to enumerator officials, though we know they were working in the family productive unit the same as they had done throughout the modern era (Le Play, 1990).

I use the Institute of Social Reforms Bulletin (Boletín del Instituto de Reformas Sociales, BIRS) and the Municipal Statistical Bulletin of La Coruña (Boletín de la Estadística Municipal de La Coruña) to reconstruct working family expenses in the city. Not all of the family members’ income was recorded in the 1924 enumerator book since it was generally household heads who declared wages. To a much lesser extent, wives, children, and relatives did so. Nonetheless, this source lets us learn whether the wage of the husband/household head allowed for the subsistence of a type 3b family (Laslett classification), comprised of two adults and three children, which described the majority A Coruña’s families. To calculate income, I consider the most representative jobs of the city’s occupational structure, which have been coded according to PSTI3. For adult men (in the active population), these jobs were the following: military and other security forces, industrial dayworker, fisherman, metalworker, stevedore, and commercial clerk. For women, the main jobs were maid, cigarette worker, seamstress, match seller, food processer, and commercial clerk. Domestic service was the principal market niche for women; most women employed as domestic servants were single. Married women and widows predominated in the tobacco industry, where 1,932 women were employed4

The enumerator book recorded day wages of the working classes but, farther up the social scale, annual income. This is the case for upper-middle class families in the liberal professions (for example, doctors and lawyers), wholesale commerce, and industry. To reconstruct the income of family heads in different productive sectors, I multiply their declared daily income by 265 workdays per year. This is similar to what colleagues and I have done for workers’ budgets in other publications (Borderías y Muñoz-Abeledo, ٢٠١٨; Borderías, Muñoz-Abeledo y Cussó, 2022). The procedure is also similar to what other researchers have done (García-Zúñiga, 2011)5. For fishermen, I have maintained the 300-workday year since this activity was normally carried out during ten months of the year (Borderías y Muñoz-Abeledo ٢٠١٨). To make declared annual incomes comparable, I convert them to daily incomes and then consider only 265 days.

On the expense side, I take the following items: food, housing, household costs (lighting and heating), clothing, and other costs. I use the diet published by Borderías, Muñoz-Abeledo, and Cussó (2022) for a family composed of two adults and three children under 10 years of age, while adding the missing nutrients that would make this diet equivalent to Allen’s “respectability basket” (2015), the most widely employed standard in recent historiography. This will allow comparative standard-of-living studies to be carried out in the international arena (Allen, 2015; Boter, 2020; Horrel, Humphries y Weisdorf, 2021, 2022; Burnette, 2024). I assume that food expenses were 65 percent of total expenses, which is the weighting used by other economic historians to construct consumer price indices and family budgets (Maluquer, 2013). The cost of housing (rent), and certain household costs (lighting and fuel), as well as minimal social expenses (education, health, leisure) have been added to the main expense, food. Costs were calculated using average prices published by BIRS, which were checked against those found in the Statistical Yearbook of Spain (Anuario Estadístico de España) and against local prices from the commerce and supply section of A Coruña’s municipal historical archives. These local files provide prices for bread, meat, vegetables, and other foods for the study year (1924).

With this methodology and these sources, I set out to learn whether standards of living for A Coruña families had improved since the prewar years and whether this was a decade of consolidation for the “male breadwinner model”. To do this, I consider a wider range of occupations from that used in the article published by Borderías, Muñoz-Abeledo, and Cussó in Revista de Historia Industrial (2022).

To construct family budgets, I select from the initial sample (6,672 individuals; 1,531 households) those families whose heads declare an occupation and an income. This gives us a sub-sample of 590 families in which, as we will see in the next section, household heads have a range of occupations. In the next step, I look at 3b families (two adults and 3 children less than 10 years of age), which reduces the number of families to 389. Twenty-five percent of the wives in these families declare income.

3. Occupational Structure of A Coruña

Throughout the 19th century and early 20th century, A Coruña, with its dynamic economy and robust commercial activity, was the main urban center of Galicia. (By the 1930s, Vigo would take the lead, becoming Galicia’s principal industrial city.) During the first third of the 20th century, A Coruña’s population nearly doubled. See Table 1.

Table 1: Population Trends in Galicia, 1887–1940

|

1887 |

1900 |

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

|

|

A Coruña |

37,251 |

43,971 |

47,984 |

62,022 |

74,132 |

|

Vigo |

14,947 |

15,926 |

23,144 |

41,500 |

53,614 |

|

Galicia |

1,894,558 |

1,980,515 |

2,063,589 |

2,124,244 |

2,230,281 |

Source: Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Censos de Población.

The increase in A Coruña’s population was due in part to immigration from rural areas in the provinces of Lugo and A Coruña. This led to urban growth and greater demand for workers associated with construction, industry, and services. Since the second half of the 19th century, the city had been characterized by a diverse economic and work structure, which leaned mainly toward commerce and services. The tertiary sector consolidated itself during first third of the 20th century. Throughout this period, A Coruña’s position as port and provincial capital allowed its service sector to modernize. Benefitting from its location as a port, the city functioned as a thriving hub for intraregional, interregional, and foreign trade. But it was not just an axis for the trading sector—commercial activity also had a great impact on the wider urban economy, bringing A Coruña up to the level of Spain’s other medium-sized coastal cities. Trade thus constituted a way to canalize wealth, generating prosperity from its maritime businesses and also from its coastal and overseas commerce6.

Before proceeding with the reconstruction of family budgets, I will outline A Coruña’s labour market, which will give us an idea of men and women’s principal occupations. Women’s occupations give a good indication of the importance of their contribution to family economies and standards of living.

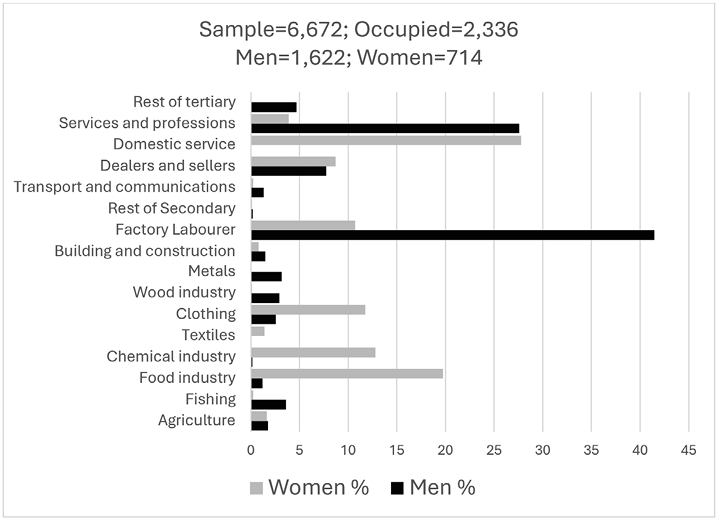

Graph 1: Occupational Structure of A Coruña, 1924

Source: Padrón de 1924 de A Coruña (Enumerator Book of Population in A Coruña)

Although my main source is the municipal enumerator book of 1924, I have compared its occupational data with those of the 1920 census. Even though the latter document under-reports women’s activity (Muñoz-Abeledo, Verdugo Matés y Cañal-Fernández, 2019), it is useful for identifying the main occupations of men and women7. According to the census, A Coruña’s most developed sector was the tertiary, with almost half the city’s occupied population, followed by the secondary and primary sectors. See Table 2.

As Table 2 and Graph 1 show, the primary sector was not very important in terms of occupied population, despite the city’s prominence as a commercial and fishing port. The port concentrated workers who unloaded and traded fresh fish, but not all fishermen lived in the capital. Many came from provincial fishing towns and sold their catch in A Coruña’s fish market (Carmona, 1997; Giráldez, 1996). According to census data, there were 918 fishermen in the city in 1924. This would constitute 4.3 percent of men’s total occupation, a figure similar to that derived from the population sample drawn from the 1924 enumerator book (Graph 1).

Table 2: Population Distribution by Sector, A Coruña, 1900–30

|

Year |

Primary Sector |

Secondary Sector |

Tertiary Sector |

|

1900 |

18.27 |

30.76 |

50.97 |

|

1910 |

18.16 |

29.89 |

51.94 |

|

1920 |

8.28 |

45.52 |

46.2 |

|

1930 |

2.74 |

47.23 |

50.03 |

Source: Spanish Institute of Estatistics, Censuses of 1900-1930.

Regarding the secondary sector, 43 percent of the men in my sample stated that they were factory day labourers (see Graph 1). Fish processing, a traditional industry of the city, followed an important development path and helped stimulate other industries, such as metallography, containers, wooden crates, and ice, all of which mainly employed men. Women were very important in the tobacco industry, which, according to data from BIRS, employed 1,933 women during the first half of the 1920s8. In our sample, 13.4 percent of the active population of women worked in the city’s tobacco factory. A similar number—13 percent of active women—worked in clothes-making, while 1.5 percent were occupied in local table linen factories. The food industry was made up of, among other things, several salting and canning factories, which employed 7.8 percent of the city’s occupied women.

Finally, with respect to the tertiary sector, A Coruña was an eminently commercial city by the first part of the 20th century. In fact, according to figures from Industrial and Commercial Taxation of 1924, 32 percent of businessmen were storekeepers while 24 percent were occupied in other services (Precedo Ledo and Sánchez Arévalo, ١٩٨٩). Data from the 1924 enumerator book show that commercial occupation was quite similar for men and women—8 percent and 9 percent, respectively (see Graph 1). However, gender segmentation occurred within commercial activities. While men situated themselves in the wholesale trades, women were found in retail commerce: grocery stores, haberdasheries, and shops selling fabrics for sewing clothes and textiles for the home. The city’s commercial dynamism increased the supply of services in the hospitality industry: cafés, restaurants, hostels, inns, and bars (Mirás, 2004; Lindoso and Mirás, 2001); where women’s presence was significant (Muñoz-Abeledo, Verdugo Matés y Cañal-Fernández, in press).

In the tertiary sector, after commerce, occupations linked to the armed forces stand out for men (10 percent), and occupations in domestic service for women (31 percent). Soldiers and maids filled A Coruña’s urban promenades in the 1920s. These are followed by the “liberal professions” and those related to public services (education and health), then private services, especially those associated with business activities, such as lawyers, notaries, commercial agents, and commission agents.

Now that we have a description of the city’s economic and occupational structure, we can look more closely at men and women’s remuneration in the principal occupations and sectors.

4. Family Incomes

In this section I examine family incomes according to the occupational groups used in PSTI coding (explained above, in Methodology and Sources). This allows me to determine whether the head of household was the main breadwinner, and the wife made an important monetary contribution to the family economy, especially critical in the case of 3b families, whose children were still not active. Recall that of the 1,531 households in the initial sample, I ended up with just 594 because only those families that declared incomes—at least by the head of household (38.9 percent of all households)—are taken into account.

Table 3 shows average daily income for heads of family and their wives by occupational group. It should be noted that working class families recorded day wages in the enumerator book and, within these families, not all wives declared incomes. This is the case of the first group of farm labourers and cattle workers (primary sector). Here, wives were in charge of the house, kitchen garden, and animals, and distributed products (such as vegetables, cheese, milk, chickens, eggs, and rabbits) to nearby markets, but did not declare incomes to enumerator officials (Muñoz-Abeledo and Verdugo Matés, 2023). The same is true for women responsible for commercial and hostelry activities, who appeared in industrial registration records and commercial guides but who also did not declare income in the enumerator book.

Table 3: Income of Family Heads and their Wives by Occupational Group, A Coruña, 1924

|

Professional Group |

PSTI Code |

Average Daily Income FH |

Average Daily Income W |

Income of the Two Adults |

FH Contribution % |

W Contribution % |

|

PRIMARY SECTOR |

||||||

|

Farm Labourer, Cattle Worker |

1,1,0,1,1,1 |

4.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

Fishermen, Assistant to fishing |

1,4,0,0,1,2 |

4.9 |

2.0 |

6.9 |

71.0 |

28.9 |

|

SECONDARY SECTOR |

||||||

|

Industrialist, Entrepreneur |

2,2,0,0,7,0 |

12.5 |

1.9 |

14.5 |

86.4 |

13.5 |

|

Industrial Day Labourer |

2,2,0,0,5,0 |

5.4 |

2.8 |

8.3 |

65.6 |

34.3 |

|

Clothing |

2,210,1,0,1 |

5.5 |

2.0 |

7.5 |

73.3 |

26.6 |

|

Tobacco Industry |

2,2,3,0,2,1 |

6.0 |

5.0 |

11.0 |

54.5 |

45.4 |

|

Glass Industry |

2,2,46,1,0,2 |

7.3 |

|

|

||

|

Building |

2,3,80,1,30,1 |

6.3 |

|

|

|

|

|

Traditional Trades |

2,0,0,0,2,0 |

5.7 |

2.7 |

8.4 |

67.9 |

31.9 |

|

TERTIARY SECTOR |

||||||

|

Liberal Professions |

3,5,35,0,0,0 |

11.4 |

6.8 |

18.3 |

62.5 |

37.4 |

|

Commerce |

3,4,0,0,0,0 |

12.6 |

|

|

|

|

|

Hostelry |

3,5,1,0,0,1 |

3.4 |

4.0 |

7.4 |

46.0 |

53.9 |

|

Skilled Merchant Marine |

3,6,4,0,2,3 |

12.7 |

2.0 |

14.8 |

85.9 |

14.0 |

|

Military and Security Forces, Official |

3,5,50,0,0,1 |

16.6 |

||||

|

Military and Security Forces, Soldier |

3,5,50.1.1.5 |

6.9 |

2.5 |

9.4 |

73.4 |

26.6 |

|

Transport and Communications |

3,6,0,0,1,0 |

8.4 |

|

|

|

|

|

Other Services |

3,8,0,0,0 |

5.7 |

|

|

|

|

|

Total families = 594 |

||||||

Source: Padrón de 1924 de A Coruña.

As Table 3 shows, the families with the greatest income were those whose household heads were industrialists, storekeepers, one of the liberal professions, or skilled merchant marines (for example, ship captain). If the wives in these groups reported some type of activity, then family incomes increased, nearing or even surpassing those reported by entrepreneurs and industrialists. This is the case of the spouses of workers in the liberal professions who were associated with education (teachers) and healthcare (doctors and nurses). When the wages of both spouses are added, family income rises considerably.

In any case, there was a clear income ladder for men heads of households in which the highest steps corresponded to occupational groups mentioned above while the lowest steps were reserved for occupations in the primary sector (agriculture and fishing), together with hostelry services. However, it must be noted that family heads in the latter occupations would have received in-kind payments that were not taken into consideration in their statements to enumerator officials.

For skilled workers as well as storekeepers, and industrialists, the household head was the main or, in some cases, sole breadwinner, as women’s participation rates were low or null in these groups (Muñoz-Abeledo, Verdugo Matés and Taboada Mella, 2019). Section 6 will examine which occupations provided fathers with sufficient income for reproduction of the family unit.

It is also interesting to look at women’s income. For some occupations, there was a wage gap of up to 50 percent, accompanied by the effects of labor segmentation. Take, for example, the occupations related to the city’s maritime activities. While, according to enumerator data, fishermen’s average daily income was 4.9 pesetas, women who worked in auxiliary activities (making and repairing nets, cleaning boats, loading and unloading boxes of fish), as port workers, or in salting and canning factories were remunerated an average of 2 pesetas per day, which meant a wage gap of more than 50 percent compared to their fishermen husbands. These data have been checked against other sources, such as BIRS (Number 208, October 1921), and reports from Rodríguez Santamaría, a specialist in the field.

These day wages or salaries rise to the following: for steam trawling, from 5 to 6 pesetas; for those catching sardines in the lower estuaries of Galicia about 5 pesetas a day . . . The rest of Spain’s fishermen received a day wage of 3 or 4 pesetas . . . About 40,000 people are employed in canning in Spain, with a minimum wage of 1.5 pesetas and a maximum of 3.5 for women and 8 pesetas for men. (Rodríguez Santamaria, 1923: 16)

If we focus on the main labor categories of the secondary sector—craftspeople and factory dayworkers—we see that the gender wage gap is maintained within each category and that average incomes are similar for men in the trades and factories—and also for craftswomen and women workers (see Table 3). Looking ahead (to the next section), we can now guess that these families will have similar standards of living, assuming that they have the same family expenses. Gender segmentation also occurred in the clothes-making industry, which was essentially composed of tailors and seamstresses. The highest wages in this sector went to workers in tobacco and glass, with women cigarette workers earning the highest incomes among women occupied in industry. Finally, glassworkers were the best paid, which had been true since the industry established itself in the city in the 19th century (Muñoz-Abeledo, Taboada Mella and Verdugo Matés, 2015).

In general, workers in the tertiary sector were the most highly remunerated. Average incomes for family heads were quite similar in the liberal professions and commerce, with the highest incomes going to skilled merchant marines and military officials.

In the working classes, the father and mother’s contributions were most equal in hostelry, given that, as mentioned earlier, women themselves managed businesses in this industry (inns, taverns, cafés), or did so with their husbands, which is why women’s contributions were even greater than their husbands’ (54 percent). Excluding the tobacco industry, men’s contributions ranged from 65 to 86 percent of family income, while women’s ranged from 14 to 34 percent. These percentages are practically identical to those derived from an analysis of incomes in the capital of Zaragoza (Marco, Gracia y Delgado, 1924). Among industrial activities, women cigarette workers stand out for they had the highest wages (45.5 percent). Next come women dayworkers in other industries (34.97 percent), craftswomen (31.9 percent), women canners (28.9 percent), women dressmakers (26.6 percent), and the wives low-ranking military personnel (26.6 percent).

Incomes of Laslett’s 3b Nuclear Families

In this study, I have wanted to delve more deeply into families in the first section of the family cycle, that is, those with inactive children. The 3b nuclear family of Laslett’s classification is significant in quantitative terms—25.40 percent of the households in our sample for A Coruña in 1924. Table 4 shows the occupations of adult members of these families, together with their declared incomes in the enumerator book. For agricultural day labourers (from the city’s periphery), fishermen, and factory dayworkers, this income was a daily wage. For families whose fathers worked in one of the liberal professions or in commerce, the recorded incomes were annual, which I have reduced to day wages by dividing by 365.

Table 4: Occupations and Day Wages (pesetas) of Adult Members of 3b Families (Laslett) with Children < 10 years, 1924

|

Professional Group |

Family Head % of Occupation |

Average Day Wage |

Wife % of Occupation |

Average Day Wage of Wife |

|

PRIMARY SECTOR |

||||

|

Farm Labourer, Cattle Worker |

0.8 |

3.00 |

3.7 |

|

|

Fishermen |

6.7 |

5.00 |

||

|

SECONDARY SECTOR |

||||

|

Food Industry |

1.3 |

3.7 |

||

|

Fish Canning |

23.4 |

2.00 |

||

|

Tobacco Industry |

11.2 |

2.40 |

||

|

Clothing |

5.50 |

18.7 |

1.75 |

|

|

Metal |

3.6 |

7.00 |

||

|

Construction |

5.1 |

6.30 |

||

|

Industrial Dayworkers |

50.4 |

5.60 |

13.1 |

2.80 |

|

TERTIARY SECTOR |

||||

|

Transport and Communications |

1.5 |

8.44 |

1.9 |

|

|

Commerce |

5.1 |

12.65 |

12.1 |

4.94 |

|

Domestic Service |

5.6 |

1.50 |

||

|

Liberal Professions |

25.5 |

11.48 |

6.6 |

6.86 |

|

Total Families = 389 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

||

Source: Padrón de Población de 1924, A Coruña

5. Family Expenses

In this section, I consider the main expense items gathered by Family Budget Surveys (Encuestas de Presupuestos Familiares) since they were first published in Spain in 1958: food, housing, household expenses (lighting and fuel), clothing, and other costs. Starting here, and taking incomes into account, I will construct family budgets that allow us to better understand standards of living in A Coruña, with a special focus on families that achieved the conditions of the “male breadwinner model”. I will also examine how the families of workers and fishermen lived in this port city, as well as the purchasing power of middle-class families (liberal professions, military officials, shopkeepers).

To reconstruct the main expense item, food, I chose a basket that provides the quantities needed for family reproduction in conditions of good nutrition, similar to Allen’s “respectability basket (Borderías, Muñoz-Abeledo and Cussó, 2022) and consisting of 20 products that align with those recorded by the BIRS for La Coruña (1920, 1924) and by the Municipal Statistical Bulletin of La Coruña (1920). I have checked the data on local prices against those recorded in the Statistical Yearbook of Spain (ANE) for the city. I have also used ANE’s prices for 1929, thus providing a general picture of the evolution of the cost of living in the 1920s. Housing rent data have been taken from BIRS (1921–22), and the annual costs of light and heating were also taken from these bulletins and yearbooks. See Table 5.

As can be seen in Table 5, the cost of a working family’s food basket—and of the family’s annual expenses—were quite constant. Given the stability of consumer prices during the decade, this is not surprising (Maluquer, 2006, 2013). Spending on food sets the course of family expenses (65.70 percent). Rental expenses are assumed to be stable because rental agreements were generally for indefinite periods and had fixed payments (Maluquer, 2006). Now that annual expenses have been calculated, I can do the same with incomes.

Table 5: Annual Expenses of a 3b Working Family in A Coruña (1920–1929)

|

Food (65,7%) |

Rent (10%)* |

Household Expenses (11.2%) |

Other Expenses (13.1%) |

Annual Expense (100%) |

|

|

1920 |

1,629.54 |

150 |

127.75 |

270.22 |

2,177.50 |

|

1924 |

1691.00, |

150 |

80.30 |

279.10 |

2,200.40 |

|

1929 |

1,499,24 |

150 |

76.75 |

274.88 |

2,000.87 |

Sources: Boletín del Instituto de Reformas Sociales (1920, 1924), Anuario Estadístico de España (1929).

Note: Weightings are taken from Maluquer (2013). Rent data come from BIRS for the first years of the 1920s. Rental prices are assumed to remain stable through the second half of the decade.

Table 6: Annual Family Income and Expenses, A Coruña, 1924. Taking into account only the income of the family head

|

Occupational Category |

Income FH |

Total Expense |

Deficit/Surplus |

|

PRIMARY SECTOR |

|||

|

Farm Labourers/Cattle Workers |

900.00 |

1,478.06 |

-578.06 |

|

Fishermen |

1,500.00 |

2,081.70 |

-581.70 |

|

SECONDARY SECTOR |

|||

|

Industrialist |

3,328.40 |

2,132.34 |

1,196.06 |

|

Industrial Day Labourer |

1,484.00 |

2,132.34 |

-647.00 |

|

Clothing |

1,457.50 |

2,132.34 |

-674.84 |

|

Tobacco Industry |

1,590.00 |

2,132.34 |

-542.34 |

|

Glass Industry |

1,945.10 |

2,132.34 |

-187.24 |

|

Construction |

1,669.50 |

2,132.34 |

-462.84 |

|

Traditional Trades |

1,529.05 |

2,132.34 |

-603.29 |

|

TERTIARY SECTOR |

|||

|

Liberal Professions |

3,042.20 |

2,132.34 |

909.86 |

|

Commerce |

3,352.25 |

2,132.34 |

1,219.91 |

|

Hostelry |

903.65 |

2,132.34 |

-1,228.69 |

|

Skilled Marine |

3,381.40 |

2,132.34 |

1,249.06 |

|

Military and Security Forces |

3,134.95 |

2,132.34 |

1,002.61 |

|

Transport and Communications |

2,236,60 |

2,132.34 |

104.26 |

|

Other Services |

1,534.35 |

2,132.34 |

-597.99 |

Sources: Padrón de Población de 1924, A Coruña, Boletín del Instituto de Reformas Sociales (1924), Anuario Estadístico de España (1924)

6. Family Budgets

With incomes and expenses calculated (in earlier sections), family budgets can be reconstructed. I carry out two exercises. On the one hand, I want to establish which occupational categories fulfilled the “male breadwinner model”. On the other, I confirm that families with two incomes (from adult members) would have a budgetary surplus. Also, the household production of agricultural and fishing families must be taken into account, since these families would not need to turn to the marketplace to acquire some of the food items in their consumption basket9.

Table 6 shows the main results of this family budget analysis. First, it establishes which of men’s occupations in A Coruña fulfilled the “male breadwinner model” in the 1920s. The city’s middle and upper classes—liberal professions, industrialist, storekeepers, skilled workers in the local fleet, and soldiers from the middle and upper ranks—covered this standard budget very well. The same can be said about other Spanish cities where family budgets based on the enumerator book of 1924 have been analyzed, such as Zaragoza (Gracia and Delgado, 2024) and Barcelona (Borderías and Cussó, 2023). The other occupational categories incurred deficits, failing to attain the conditions for the “family wage model”. Primary sector workers—fishermen and farmers—did not reach the model, even though I have given them lower food expenses due to household production. With the exception of workers in transportation and communications, the rest of the secondary and tertiary sectors did not either. To sum up, assuming people worked 265 days each year in industry and services, they would need a wage of 8 pesetas per day in order to meet essential expenses. Therefore, workers in these categories either had to work more days or extra hours. Another alternative was having more than one job. Any of these possibilities could have assured a balanced family budget in 1924. Admittedly, wages rose slightly in the second half of the decade, while prices remained stable, so standards of living tended to improve. As colleagues and I have shown in an earlier article, some of the construction trades (bricklayers, stonemasons attained a family wage at the end of the 1920s (Borderías, Muñoz-Abeledo, and Cussó, 2022).

What happens when both adult members of the family unit work, and their incomes are added together?

Table 7: Family Incomes and Expenses, A Coruña, 1924

|

Families by Occupation of FH |

Husband’s Inc. |

Wife’s Inc. |

Couple’s Inc. |

Total Expense |

% FH Expense |

% Wife Expense |

Deficit/Surplus |

|

PRIMARY SECTOR |

|||||||

|

Fishermen |

1,500.0 |

530.00 |

2,030.00 |

2,081.7 |

73.89 |

26.10 |

-51.7 |

|

SECONDARY SECTOR |

|||||||

|

Industrial Day Labourer |

1,484.0 |

757.90 |

2,241.90 |

2,132.3 |

69.62 |

35.55 |

109.2 |

|

Clothing |

1,457.5 |

530.00 |

1,987.50 |

2,132.3 |

68.35 |

24.85 |

-144.8 |

|

Tobacco Industry |

1,590.0 |

1,325.00 |

29150 |

2,132.3 |

74.56 |

62.14 |

782.6 |

|

Glass Industry |

1,945.1 |

707.50 |

2,652.65 |

2,132.3 |

91.22 |

33.18 |

520.2 |

|

Traditional Trades |

1,529.1 |

718.15 |

2,247.20 |

2,132.3 |

71.70 |

33.67 |

114.8 |

|

TERTIARY SECTOR |

|||||||

|

Liberal Professions |

3,042.2 |

1,817.90 |

4,860.10 |

2,132.3 |

142.66 |

85.25 |

2,727.7 |

|

Hostelry |

903.6 |

1,060.00 |

1,963.65 |

2,132.3 |

42.37 |

49.71 |

-168.6 |

Sources: Padrón de Población de 1924, A Coruña, Boletín del Instituto de Reformas Sociales (1924), Anuario Estadístico de España (1924).

As can be seen in Table 7, when the incomes of family heads and their wives are added together, either the family’s budgetary deficit is greatly reduced, as in the case of fishermen and women canners, or a balance is reached, as occurred with industrial day labourers and with families linked to specific industries, such as tobacco, a large employer of women in the city. Of course, within the ranks of the liberal professions, couples in the teaching or healthcare sectors already had respectable standards of living.

In general, the working classes’ normal practice was to add spouses’ incomes since men’s wages did not cover the survival needs of families in the first part of the 20th century (Arbaiza, 2000).

7. Conclusion

During the first third of the 20th century, the working classes of urban Spain generally did not achieve the conditions of the “male breadwinner model” (Borderías, Muñoz-Abeledo y Cussó, 2022). Recent publications for the cases of Barcelona and Zaragoza confirm this (Borderías y Cussó, 2023; Marco Gracia y Delgado, 2024). My results for the city of A Coruña corroborate this hypothesis and deepen our understanding with a micro-historic analysis based on statistical sources (Municipal Statistical Bulletin of La Coruña, Institute of Social Reforms Bulletin, Statistical Yearbook of Spain) and social reports. The goal has been to determine standards of living for a greater number of socioeconomic sectors and occupational categories, always from a gender perspective, while taking into account men and women’s contributions to family incomes. Using the “welfare ratios” proposed by Allen (2015), and adapting his diet to the consumption norms of residents of A Coruña, I have reconstructed the essential expenses of nuclear families composed of two adults with three children less than 10 years of age. I have reconstructed a diet that, according to FAO standards, provided the nutrients needed to ensure healthy living conditions. I have also reconstructed the cost of renting working-class housing, household expenses (lighting and fuel), and other expenses, so that I could devise a standard budget for a representative type of family (3b nuclear) for A Coruña in the middle of the 1920s.

According to my calculations, a head of household needed to earn 8 pesetas each day in order to take on the main expense items in 1924. Who reached this “male breadwinner model”? In reality, none of the occupations of the primary or secondary sectors did. Of the workers in the secondary sector, only glass industry workers—who had enjoyed high wages since the middle of the 19th century—came close to the model yet still incurred small budget deficits in 1924. The “family wage” was attained by skilled workers in the service sector (liberal professions, commerce, marine, soldiers) and workers in transportation and communications.

If the incomes of men and women are added together—wives’ incomes were half the wages of heads of family—the standards of living of industrial workers and craftsmen are substantially improved. Among families with two incomes in the secondary sector, only those in the clothing subsector had a deficit. In the tertiary sector, families in hostelry had deficits. In these cases, declared incomes, which were mainly from family businesses, might be underestimated since they varied according to sales and/or production volumes. Such data are not as precise as those coming from wages. Regarding families who were dependent on the primary sector (agricultural and fishing) it is important to emphasize that they incurred deficits even though we accounted for household production while reconstructing their expenses. We know that agricultural families produced for the market but also for domestic consumption and that fishermen received in-kind payments (a percentage of the fish sold at market). Thus, families in the primary sector did not have to turn to the market in order to supply themselves with certain products (for example, bread, fish, potatoes, vegetables).

In short, if only the income of the head of household is taken into account, 33 percent of the families in my population sample would have achieved the “family wage model”. Such families worked mainly in the tertiary sector. If wives’ contributions to family incomes are considered, this percentage rises to 87 percent of the families in the sample.

References

ALLEN, Robert (2015): “The high wage economy and the industrial revolution: a restatement”, Economic History Review, 68 (1), pp. 1-22.

ARBAIZA VILALLONGA, Mercedes (2000): “La cuestión social como cuestión de género: Feminidad y Trabajo en España (1860-1930)”, Historia Contemporánea, 21, pp. 395-458.

BORDERÍAS, Cristina and MUÑOZ-ABELEDO, Luisa (2018): “¿Quién llevaba el pan a casa en la España de 1924? Trabajo y economías familiares de jornaleros y pescadores en Cataluña y Galicia”, Revista de Historia Industrial, 74, pp. 77-106.

BORDERÍAS, Cristina; MUÑOZ-ABELEDO, Luisa and CUSSO, Xavier (2022): “Male breadwinners in Spanish cities (1914-1930)”, Revista de Historia Industrial, 84, pp. 59-98.

BORDERÍAS, Cristina and CUSSÓ, Xavier (2023): “Male Wages, Household Budgets and Living Standards of Barcelona’s Working Class (1856-1917)”, Investigaciones de Historia Económica, 19, pp. 3-21.

BOTER, Corinne (2020): “Living standards and the life cycle: reconstructing household income and consumption in the early twentieth-century Netherlands”, Economic History Review, 73, pp. 1050–1073.

BURNETTE, Joyce (2024): “How not to measure the standard of living: Male wages, non-market production and household income in nineteenth-century Europe”, Economic History Review, DOI: 10.1111/ehr.13339.

GARCÍA-ZÚÑIGA, Mario (2011): “La evolución de los días de trabajo en España, 1250-1918” Comunicación, X Congreso Internacional de la Asociación Española de Historia Económica, Sevilla.

HORRELL, Sara; HUMPHRIES, Jane and WEISDORF, Jacob (2021): “Family standards of living over the long run, England 1280-1850”, Past and Present, 250, pp. 87–134.

HORRELL, Sara, HUMPHRIES, Jane and WEISDORF, Jacob (2022): “Beyond the male breadwinner: life-cycle living standards of intact and disrupted English working families, 1260-1850”, Economic History Review, 75, pp. 530–560.

LE PLAY, Fréderic; SIERRA ÁLVAREZ, José; DOMÍNGUEZ MARTÍN, Rafael (1990): Campesinos y pescadores del norte de España: tres monografías de familias trabajadoras a mediados del siglo XIX. Madrid: Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente.

LINDOSO TATO, Elvira and MIRÁS ARAUJO, Jesús (2001): “La trayectoria de una economía urbana. A Coruña (1868-1936)”, in El republicanismo coruñés en la historia. A Coruña, Ayuntamiento (ed. lit.), pp. 31-38.

MALUQUER DE MOTES, Jordi (2006): “La paradisiaca estabilidad de la anteguerra. Elaboración de un índice de precios de consumo en España”, Revista de Historia económica, 24 (2), pp. 333-382

MALUQUER DE MOTES, Jordi (2013): “La inflación en España. Un índice de precios de consumo, 1830-2012”. Estudios de historia económica, 64, pp.1-147.

MARCO-GRACIA, Javier and DELGADO, Pablo (2024): “So rich, so poor. Household income and consumption in urban Spain in the early twentieth century (Zaragoza, 1924)” Documento de Trabajo 2024-01 Facultad de Economía y Empresa Universidad de Zaragoza.

MIRAS ARAUJO, Jesús (2004): “El puerto y la actividad económica en la ciudad de A Coruña, 1914-1935” Scripta Nova: Revista electrónica de geografía y ciencias sociales, 8, pp. 157-180.

MIRAS ARAUJO, Jesús (2009): Un proyecto de historia urbana centrada en una ciudad media: A Coruña y su evolución económica. En Delgado Viñas, C., Rueda Hernanz, G. e Sazatornil Ruiz, L., Historiografía sobre tipos y características históricas, artísticas y geográficas de las ciudades y pueblos de España, Santander, pp. 201-206.

MUÑOZ-ABELEDO, Luisa, TABOADA-MELLA, Salomé and VERDUGO-MATÉS, R.M. (2015). “Condicionantes de la actividad femenina en la Galicia de mediados del siglo XIX”. Historia Agraria 79, pp. 39-80.

MUÑOZ-ABELEDO, Luisa, TABOADA-MELLA, Salomé, and VERDUGO-MATÉS, Rosa.M. (2019): “Determinantes de la participación femenina en el mercado de trabajo en la Galicia rural y urbana de 1924”. Revista de Historia Industrial, 24, pp. 161-186.

MUÑOZ-ABELEDO, Luisa and VERDUGO-MATÉS, Rosa (2023). “New Evidence for Women’s Labor Participation and Occupational Structure in Northwest Spain, 1877-1930”. Journal of Interdisciplinary History LIII (4), pp. 571-598.

PRECEDO LEDO, Andrés and SÁNCHEZ ARÉVALO Juan (1989): “Los cambios en la estructura demográfica familiar y su difusión en el sistema de asentamientos humanos en la provincia de la Coruña”, Semata: Ciencias sociais e humanidades, 2, (Issue dedicated to: Parentesco, familia y matrimonio en la historia de Galicia, José Carlos Bermejo Barrera (cord.)), pp. 205-216.

RODRÍGUEZ SANTAMARIA, Benigno (1923): Diccionario de artes de pesca de España y sus posesiones Madrid, Sucesores de Rivadeneyra.

1 For each family member, the following information is gathered: 1) name, 2) sex, 3) date and place of birth, 4) nationality, 5) civil status, 6) relationship to head of household or reason for living there, 7) whether the person can read or write, 8) main job or way of making a living, 9) legal residence, 10) time living in the town/district where the person is registered, 11) location where absent family members can be found, 12) classification of neighborhood residents, 13) annual or daily income.

2 The population/sample size coefficient (N/n) is calculated. Then a number between 1 and the coefficient is drawn. This will be the initial page selected. The coefficient is then added successively to the sum to obtain the rest of the pages for each district.

3 PSTI coding has been followed for occupational structure because it better situates occupations at the sectoral level. Cambridge Group for the History of Population and Social Structure (https://www.campop.geog.cam.ac.uk/research/occupations)

4 According to the 1924 enumerator book, 44 percent of women cigarette workers were married, 37 percent were widows, and 19 percent were single.

5 According to García-Zúñiga, subtracting only the holidays from the ecclesiastical calendar, there were an average of 296 theoretical workdays in 1900 Spain (García Zúñiga, 2011 p. 67). If we then subtract days for sickness, normal crises, and unexpected events, we would arrive at 262 workdays.

6 Muñoz-Abeledo, Taboada Mella, Verdugo Matés. (2015); Miras Araujo, J. (2009)

7 The 1920 census classifies workers into 80 industrial and professional groups: agriculture, industry, and commerce (groups 1–47); military and police (48–50); administration (51–52); religion and clergy (53–56); liberal professions (57–65); people who live from rent (66–67); retired and pensioners of the state and other public and private administrations (68); domestic servants (69); individuals temporarily without occupation (70–79). To find numbers of occupied people, I have looked at all of the groups in this census except the last ones (from 68 onward).

8 Boletín del Instituto de Reformas Sociales, nº 208, p. 504.

9 I have reduced food expenses for agricultural families by assuming that they would acquire 60 percent of food items in the market; the rest would come from home production. This seems realistic because Family Budget Surveys from the 1960s still assumed 40 percent home production in the countryside. For fishing families, I have eliminated the expense for fish since this food item would be obtained as an in-kind payment that was not recorded in the enumerator book. See Encuestas de Presupuestos Familiares de 1963 and Borderías y Muñoz-Abeledo (2018).