Labour, household budget and standard of living in urban Andalusia during the “Bolshevik Triennium”: Jaén, 1920

David Martínez López, Universidad de Granada

Manuel Martínez Martín, Universidad de Granada

Gracia Moya García, Universidad de Jaén

Abstract

A noteworthy element characteristic of the majority of the mining areas was the peculiar sex ratio at the initial stage of their establishment and at times of the highest growth in the demand for labour. In general, the predominance of men in the mining area increased between 1877 and 1910, when there was a strong contribution of men from different origins with an insufficient female contribution, due partly to the type of labour and its instability.

The evolution of the sex ratio in the area displayed a trend towards equilibrium in 1897, which reflects the first stabilisation of the population of the mining area with an equal proportion of men and women. From 1910, there was equilibrium in the three municipalities which show the stabilisation of the population.

Keywords: Labour history, household budget, inequality, gender, class.

Trabajo, presupuesto familiar y nivel de vida en la Andalucía urbana durante el “Trienio Bolchevique”: Jaén, 1920

Resumen

En este texto se propone estudiar la relación entre el presupuesto doméstico y las condiciones de vida y trabajo de la población de Jaén (Andalucía) en 1920. Con este objetivo se reconstruye el ingreso de todas las familias de la ciudad y los presupuestos domésticos de las familias nucleares con hijos menores. A partir de las declaraciones salariales registradas en las cédulas de empadronamiento usadas para la elaboración del padrón de ese año, que registran una proporción muy elevada de las ocupaciones y los ingresos de la población masculina de la ciudad, y de la reconstrucción de una cesta de la compra de respetabilidad, se determina la capacidad adquisitiva de este tipo de familia por clases sociales. Para ello se ha utilizado la clasificación ocupacional PSTi y la clasificación social HISCLASS.

Palabras clave: Historia del trabajo, presupuestos domésticos, desigualdad, género, clase.

Original reception date: November 1, 2024; final version: December 15, 2024.

- David Martínez López, Universidad de Granada. E-mail: davidmartin@ugr.es; ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6949-051X

- Manuel Martínez Martín, Universidad de Granada. E-mail: mmm@ugr.es; ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3010-0374

- Gracia Moya García, Universidad de Jaén. E-mail: gmmoya@ujaen.es; ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4147-3408

Labour, household budget and standard of living in urban Andalusia during the “Bolshevik Triennium”: Jaén, 19201

David Martínez López, Universidad de Granada

Manuel Martínez Martín, Universidad de Granada

Gracia Moya García, Universidad de Jaén

Introduction

This text refers to the living and working conditions of the population of Jaén in 1920 at the time of the “Bolshevik Triennium”, when the cycle of social conflict initiated in the years at the turn of the century reached its peak in Andalusia.

The interpretation of this cycle of conflict in the Andalusian cities (Otero Carvajal and Martínez López, 2022) has fluctuated between two perspectives: one of a materialist nature, evident in the studies of Antonio María Calero and Carlos Arenas on the workers movement in Andalusia, which, without underestimating the role of the construction of an organisational fabric and an emancipatory narration inspired by proletarian internationalism, highlighted how the workers’ mobilisation cycle was a decisive element in the exacerbation of the living conditions of the popular classes. The other, which has recently come into fashion, is of a cultural and institutional nature, underlining the role of the ideological and organisation aspects, relegating the influence of the material conditions to a secondary place.

The materialistic perspective has traditionally been based on the analysis of the wage level of adult manual workers (one of the many lines of research on the Andalusian cities in this period which goes beyond this traditional view is that of Carlos Arenas on the working class population affected by tuberculosis in the city of Seville (1992)). This occurred for two reasons.

First, the information sources that have traditionally been used (Institute of Social Reforms, Statistical Yearbook of Spain, reports, etc.) provide the wage income for a small number of occupations of the adult male population. This limitation is due to the under-reporting of the female activity, which is presented in aggregate form with no distinction between age groups. Second, the classical historiographic view based on the “breadwinner” model, sanctioned with nineteenth-century liberalism, has a radical gender bias.

This text seeks to study the relationship between the household budget and the living and working conditions of the population of Jaén in 1920. A line of research opened and developed in Spain by the studies of Cristina Borderías and Luisa Muñoz-Abeledo (2018 and 2022), which are at the forefront of studies on labour, gender and standards of living in the international literature.

This study is structured around three hypotheses, derived from the knowledge obtained on social history, labour and gender in the period. The first is that the income of the adult workers could not cover the household budget and, as a result, the contribution to the income from other family members, particularly the women, was fundamental.2 The second is that, despite the collective contribution to total family income and the household budget, the standard of living of most families was low and did not guarantee optimum reproduction conditions (diet, housing, etc.) for the majority of the population. The third hypothesis is that the severe shortages and the overall situation of poverty among the majority of the population of the city in 1920 largely explains the cycle of mobilisation and social conflict of the “Bolshevik Triennium”.

The text is structured into five parts. The first refers to the tools used (sources and methodology) in the study. The second describes the demographic and occupational structure of the population. The third section analyses individual and family income. The fourth part assesses the standard of living based on the balancing of the household budget (income and domestic expenditure) and discusses the “breadwinner” model. The final section presents the conclusions.

Sources and methodology

a) Sources

Income and occupation have been reconstructed using the information from the census certificates used to elaborate the Municipal Enumerator Book of 1920. This document, which is a primary source, reflects the information provided by the head of the family to the municipal clerk responsible for recording these data. The census certificates of 1920 record information about 31,871 inhabitants of the municipality (Table 1), that is, 95.2% of the 33,444 inhabitants registered in the Population Census of 1920. This difference of 1,573 inhabitants in the size of the population recorded in the two sources is due to the loss of some of the certificates or census sheets. The reconstruction of income and the shopping basket is exclusively focused on the urban population (28,412 inhabitants) of the municipality. This restricts the analysis of the living conditions to the urban population of Jaén, which depended on labour markets, services and products to survive and among which the role of self-consumption was marginal.

Table 1. Population and households. Total number and percentage (%)

|

Population |

|||

|

Total |

Men |

Women |

|

|

Municipality |

(100) 31,871 |

15,728 |

16,143 |

|

Urban centre (city) |

(89.1) 28,412 |

13,862 |

14,550 |

|

Disperse (farmhouses) |

(10.9) 3,459 |

1,867 |

1,592 |

|

Households |

|||

|

Total |

Head of household (male) |

Head of household (female) |

|

|

Municipality |

(100) 7,827 |

6,324 |

1,503 |

|

Urban centre (city) |

(90.4) 7,072 |

5,608 |

1,464 |

|

Disperse (farmhouses) |

(9.6) 755 |

716 |

39 |

Source: Census certificates of 1920.

The census certificates of 1920 provide information on the income and occupation of the male population (Tables 2 and 3). 58.4 per cent of the active male population3 and 65.5 per cent of active male heads of household recorded an income. 85.8 per cent of the active male population and 95.9 per cent of active male heads of household recorded an income. In contrast, there is a lower level of income and occupation recording among the female population. Only 6.4 per cent of the active female population and 14.2 per cent of active female heads of household recorded an income. And only 11.6 per cent of the active female population and 22.1 per cent of active female breadwinners recorded an occupation.

Table 2. Population and households of the city with recorded income. Total number and percentage (%)

|

Population |

|||

|

Total |

Men |

Women |

|

|

Population |

(100) 28,412 |

(100) 13,862 |

(100) 14,550 |

|

Population with income |

(21.0) 5,977 |

(38.3) 5,316 |

(4.5) 661 |

|

Active population (15-65 years) |

|||

|

Total |

Men |

Women |

|

|

Population |

(100) 17,338 |

(100) 8,304 |

(100) 9,034 |

|

Population with income |

(31.3) 5,436 |

(58.4) 4,853 |

(6.4) 583 |

|

Households |

|||

|

Total |

Head of household (male) |

Head of household (female) |

|

|

Households |

(100) 7,072 |

(100) 5,607 |

(100) 1,464 |

|

Households with income |

(60.1) 4,250 |

(66.1) 3,706 |

(37.1) 544 |

|

Households with income of head of household |

(53.3) 3,781 |

(64.0) 3,592 |

(12.7) 188 |

|

Households headed by active population (15-65 years) |

|||

|

Total |

Head of household (male) |

Head of household (female) |

|

|

Households |

(100) 6,332 |

(100) 5,167 |

(100) 1,165 |

|

Households with income |

(62.0) 3,927 |

(67.3) 3,476 |

(38.7) 451 |

|

Households with income of head of household |

(56.1) 3,554 |

(65.5) 3,387 |

(14.2) 167 |

Source: Census certificates of 1920.

The occupation rate was corrected by attributing domestic production or working for the family business to the male and female active population with no record of the occupation for the head of the household. In these activities the work by family members was essential. This correction has given rise to a small increase in the active male population from 85.6% to 86.6% and a more significant increase in the active female population, from 11.6% to 17.2%.4 Hereafter, we will use the corrected rate of activity.

The information on income used, included in the census certificates under the heading “Daily wage or income” does not differ greatly from that drawn from the statistics elaborated by the Ministry of Labour or that published in the Statistical Yearbook of Spain (Annex A), although the census information displays a slight downward bias in terms of wages. This difference is probably due to the distortions caused by the synthetic and aggregated nature of the reports and statistics elaborated by the state bodies.5

Table 3. Population and households. of the city with recorded occupation. Total number and percentage (%)

|

Total |

Men |

Women |

|||||||

|

Population |

100 (28,412) |

100 (13,862) |

100 (14,550) |

||||||

|

Population with occupation |

32.0 (9,112) |

57.0 (7,900) |

8.3 (1,212) |

||||||

|

Active population (15-65 years) by sex |

|||||||||

|

Total |

Men |

Women |

|||||||

|

Population |

100 (17,338) |

100 (8,304) |

100 (9,034) |

||||||

|

Rate of activity |

47.1 (8,181) |

85.8 (7,132) |

11.6 (1,049) |

||||||

|

Corrected rate of activity |

50.5 (8,755) |

86.6 (7,196) |

17.2 (1,559) |

||||||

|

Households headed by active population (15-65 years) |

|||||||||

|

Households |

100 (6,332) |

100 (5,166) |

100 (1,166) |

||||||

|

Rate of activity of household heads |

82.3 (5,216) |

95.9 (4,957) |

22.1 (259) |

||||||

|

Active population (15-65 years) by sex Marital status |

|||||||||

|

Men |

Women |

||||||||

|

S |

C |

5 |

Without |

S |

C |

5 |

Without |

||

|

Population |

100 (3,208) |

100 (4,742) |

100 (347) |

100 ( 6) |

100 (2,953) |

100 (4,875) |

100 ( 1,191) |

100 (16) |

|

|

Rate of activity |

70.7 (2,269) |

95.9 ( 4,549) |

89.9 ( 314) |

0.0 ( 0) |

20.9 ( 619) |

2.9 ( 144) |

24.0 ( 286) |

0.0 ( 0) |

|

|

Corrected rate of activity |

72.6 ( 2,331) |

95.9 (4,550) |

90.2 ( 315) |

0.0 (0) |

25.9 ( 764) |

10.3 ( 504) |

24.4 ( 291) |

0.0 ( 0) |

|

Source: Census certificates of 1920.

The reconstruction of the household budget follows the model proposed by Cristina Borderías, Luisa Muñoz-Abeledo and Xavier Cussó (2022). This model contemplates the following expenditure items: food, heating and lighting, rent and other expenses. The cost of the food and lighting and heating expenses has been calculated with the information published in the Official Gazette of the Province of Jaén on the conditions stipulated in the supply of food and fuel to social welfare establishments in Jaén (Men’s Hospice, Women’s Hospice and Provincial Hospital) in the financial year 1920-21.6 Rent prices have been calculated with the information of the municipal census certificates of the municipality of Jaén (1920), which record information on the rent of 70.0 % of the households headed by active males. The amount for other expenses has been calculated using an estimated weighting proposed by Jordi Maluquer (2013).

Methodology

In the analysis of the occupational and social structure, two of the taxonomies traditionally used by the literature have been applied: the PSTi occupational classification (Wrigley) and the HISCLASS system (Van Leeuwen & Maas, 2011).7

The analysis of household budgets is confined to nuclear households, representative of the family system of Andalusia (Martínez López and Sánchez Montes, 2008) and forming the majority in the households in the city (Table 4). Specifically, the objective is to validate the degree to which the “breadwinner” model is applied to 3B households, according to Peter Laslett’s taxonomy8, with descendants (children) of twelve years or less ( 28.78 per cent of total households headed by active males (1,612 households)), a type of household typical of a critical period and family life course, when the children were dependent, the mother spent a large part of her time doing domestic work and caring for the children and, according to the institutional imaginary, the father’s income had to support the family.

Table 4. Family structure of the households in the urban centre

|

LASLETT type. |

Total |

Head of household (male) |

Head of household (female) |

|||||||||||

|

% |

Nº |

TMF |

TMH |

% |

Nº |

TMF |

TMH |

% |

Nº |

TMF |

TMH |

|||

|

1. Solitary |

9.9 |

697 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

4.8 |

267 |

1.0 |

1.1 |

29.4 |

430 |

1.0 |

1.05 |

||

|

2. No structure |

3.6 |

258 |

2.9 |

3.3 |

2.0 |

114 |

3.0 |

3.5 |

9.8 |

144 |

2.8 |

3.2 |

||

|

3. Nuclear |

78.0 |

5,517 |

4.2 |

4.3 |

84.7 |

4,749 |

4.3 |

4.4 |

52.5 |

768 |

3.2 |

3.3 |

||

|

3b. Spouses + children |

50.0 |

3,534 |

5.1 |

5.1 |

63.1 |

3,534 |

5.1 |

5.1 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

||

|

3b. Spouses + children < 13 years |

22.8 |

1,612 |

4.4 |

4.51 |

28.7 |

1,612 |

4.4 |

4.5 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

||

|

1 child < 13 |

6.5 |

464 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

8.3 |

464 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

||

|

2 children < 13 |

6.8 |

480 |

4.0 |

4.0 |

8.5 |

480 |

4.0 |

4.0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

||

|

3 children < 13 |

4.7 |

336 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

6.0 |

336 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

||

|

4 => children < 13 |

4.7 |

332 |

6.5 |

6.6 |

5.9 |

332 |

6.5 |

6.6 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

||

|

4. Extended |

7.9 |

559 |

5.0 |

5.2 |

8.0 |

448 |

5.2 |

5.5 |

7.6 |

111 |

4.1 |

4.2 |

||

|

5. Joint |

0.6 |

41 |

6.1 |

6.4 |

0.5 |

30 |

6.2 |

6.8 |

0.8 |

11 |

5.1 |

5.2 |

||

|

Total |

100 |

7,072 |

3.9 |

4.0 |

100 |

5,608 |

4.2 |

4.3 |

100 |

1,464 |

2.6 |

2.7 |

||

Source: Census certificates of 1920

- TMH= Number of members in the household.

- TMF = Number of members in the household - number of servants /live-in staff.

The reconstruction of income has been conducted with the declaration of the income recorded in the Municipal Enumerator Book under the “daily wage” (Annex B). In order to reconstruct the daily average income, the annual income was calculated based on the “daily wage” declared and contemplating an estimated number of working days. The assignment of this number of annual working days has been performed according to the estimates of the studies conducted at that time, the estimates indicated in the historiography and the characteristics of the occupation.

The non-manual active population [HSCLASS categories 1-2-3-4-5], who were mostly employed in stable and regular occupations, have been assigned 300 working days per year. The skilled manual active population [HISCLASS categories 6-10] (bricklayers, carpenters and shoemakers, seamstresses and dressmakers, bakers, etc.) considering that they were permanently available to work, have also been assigned 300 working days per year. The unskilled active manual population [HISCLASS categories 11-12], in the case of men, basically made up of day labourers and farmworkers, workers subject to a high degree of instability and risk of unemployment, have been assigned 240 working days, which is the average amount of days estimated by studies and reports.9 The servants, who were regularly hired by families - evident in the high percentage of monthly/annual income records, and who usually had one afternoon of rest per week (Albuera, 2006), have been assigned 317 working days per year.

The reconstruction of the family income has been carried out by adding the individual average income of the members of the household to the declared income. In the case of households with live-in servants with declared income this calculation has been performed negatively.

The household budget is based on a basic daily domestic expenditure to satisfy the vital needs to enable the population to produce and reproduce.

The daily domestic expenditure has been constructed with the items of food, heating and lighting, rent and other expenses (Annex C). The calculation of the food expenses follows the proposal of the cited authors (Borderías, Muñoz-Abeledo and Cussó, 2022), based on an apparent diet10 adapted to the characteristics of consumption and the food prices of the city at that time11. The foods making up the diet adapted to the city of Jaén covered the energy and nutrient requirements established in the apparent diet. This adaptation gives rise to an individual average diet that provides 2,574 kilocalories of energy, representing a slight reduction with respect to the 2,835 kilocalories calculated by these authors (2,835 Kcal.). However, this reduction does not prevent the average daily energy needs from being covered, which, according to these authors, are required for carrying out a moderately intense activity —2.288 kilocalories— or an intense activity—2,378 kilocalories—; a slight reduction in certain nutrients can also be observed (calcium, vitamin A and folic acid).12 When calculating the content and cost of food, the population has been segregated in terms of age and gender, differentiating the cost of food for adult males, adult women and boys and girls (under the age of 13), in accordance with the average nutritional and energy needs estimated for each of these groups (Borderías, Muñoz-Abeledo and Cussó, 2022). The prices assigned to the foods - per kilo, litre or unit - were established in the food supply auctions of the Men’s Hospice and Women’s Hospice and the Provincial Hospital of Jaén.13 The calculation of the cost of food was made by adding the consumption of each person in the family unit. The heading for heating and lighting, based on the consumption of coal and oil14, was calculated with the price of coal established in the specifications of the auction of the hospices and with the price of oil indicated in the data of the Statistical Yearbook of Spain for Jaén in 1920. The cost of rent (0.21 pesetas) is the average daily price recorded by the households of active unskilled manual workers in the Municipal Enumerator Book.15 The price for the heading of “Other expenses” (clothes, schooling, doctor, pub, barber’s, etc.) has been calculated by applying the weighting proposed by Jordi Maluquer, who estimated that these expenses amounted to 13.1 per cent of the total domestic expenditure.

With this methodology, the calculation of the cost of domestic expenses of a 3B family with three children under the age of 13 gives a result of 6.5 pesetas (Table 5 and Annex C). This monetary amount has been adapted to the rest of the 3B families with children under the age of 13 in accordance with the number of descendants (1, 2, 4, 5, etc. children), with only the expenditure on food increasing proportionately (Annex E).

The domestic expenses calculated for a 3B family with three children (6.5 pesetas) is practically identical to that estimated by J. Sagristá in 1920 (6.35 pesetas) for a 3B family in the city of Jaén with three children under the age of 13 (Annex F); the cost of the heading for food—5.09 and 5.1 pesetas— and its weight in domestic expenses is also similar —78.3 per cent and 80.3 per cent—, as is the case of the composition of Sagristá’s heading for food.16 In both cases, the cost of food of 5.09 and 5.1 pesetas, which was close to the estimate made by Luis Garrido (1990: 445) for the cost of food in 1920 of a working-class family in the province of Jaén (5.17 pesetas) made up of the spouses and two children under the age of 13.17

Table 5. Daily domestic expenditure of a 3B family with five members (two adults and three children under the age of 13). Jaén, 1920.

|

Pesetas |

% |

|

|

Food |

5.09 |

78.3 |

|

Fuels |

0.35 |

5.4 |

|

Rent |

0.21 |

3.2 |

|

Other expenditures |

0.85 |

13.1 |

|

Total |

6.50 |

100.0 |

Source: Annex C.

Occupation

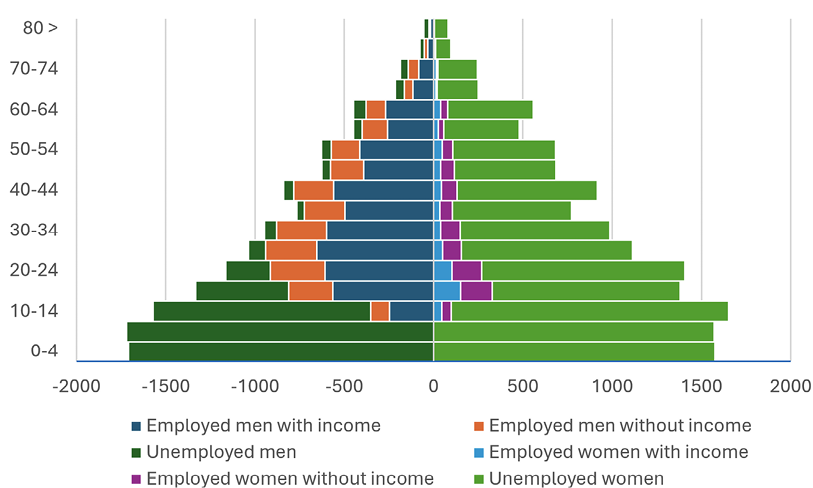

The activity of the male population was very high and these workers remained active throughout their lives (Table 3; Graphs 1 and 2). Men joined the workforce at an early age, during their youth and even childhood. By the time they were twenty most males were working, this was when they married and began to have children, and in adulthood they were practically all employed, as indicated by the high rate of activity of the male population of 15-65 years (86.6%) until old age. In contrast, according to the census information, the activity of the female population was very low —17.2 % of the total female population of 15-65 years old— and mainly restricted to young unmarried women and widows.

Graph 1. Urban population of Jaén in accordance with occupation and declared income, 1920

According to this description, the labour model prevailing in the city was structured around a radical sexual division. This model connected men to paid work and women to unpaid domestic work. In order for this model to be plausible and for the majority of women to not partake in paid work for all or most of their lives, the “breadwinner” and solvency of the male family wage was a necessary condition, requiring a critical level of male wage earnings. However, the average level of male earnings was very low.

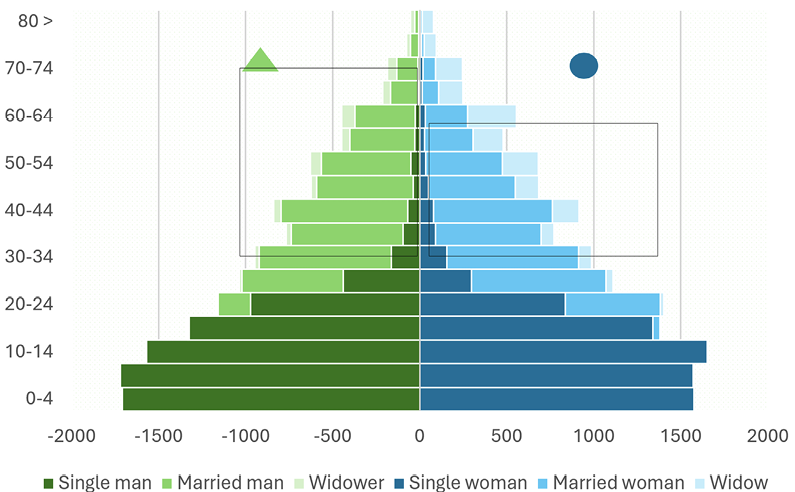

Graph 2. Population according to civil status. Jaén, 1920

The level of income was determined by the characteristics of the occupational structure of the city. The tertiary sector employed more male workers (Table 6). It was mainly based on trade, services and the transport demanded by a growing population; public services provided by the city as a provincial capital; and also the requirements of the population of the large rural hinterland of its district and bordering districts. The sector employed more than a quarter of the male active population and almost a third of the households with male breadwinners. This sector was heterogeneous and generated the majority of non-manual work. It was mainly made up of salesmen (traders and sales assistants), professionals, municipal and public administration workers, transport workers, commercial agents and administrative staff.

In terms of the proportion of active males employed, the tertiary sector was followed by the primary sector. The city, which was connected to a large agricultural environment (Hernández Armenteros, 2000), was home to a large group of agricultural workers accounting for 18.9 per cent of the male active population and more than a fifth of the households with male breadwinners. A small portion of these assets were market gardeners who farmed the irrigated lands surrounding the city. The majority were temporary agricultural workers, dependent on the demand for daily labour of the small and medium-sized farms and the large estates engaged in cereal and olive production in the large municipal area (426 hectares). The work of the agricultural labourers was seasonally distributed, concentrated in the peaks of labour demand (Garrido, 1990: 630-640), during the four summer months of cereal harvesting and during the almost five months of olive harvesting in winter. The duration of the labour season fluctuated between eight and nine months, which, however, could be shorter in years of drought or frosts and poor crops, and could be cut short when the labourers were taken ill (Garrido, 1990b: 548-525 and 630-655).18

The secondary sector employed a smaller proportion of workers, 16.7% of the active male population and 17.5% of households with active male breadwinners. The industrial fabric of the city was lean and traditional, confined to needs for housing and consumer durables of the urban population and the provision of implements to farming families in the rural area surrounding the city. Bricklayers and painters represented almost half of the workers in the sector, engaged in home construction and repair. The rest were employed in the mending and manufacture of shoes (shoe and espadrille makers) or tailoring. The majority were manual workers, who, as self-employed or wage-earning workers, formed small craft of domestic production units.

Finally, the day labourers carrying out several jobs constituted a group representing a quarter of the male active population and 27.5 per cent of the households with male breadwinners. These workers, who were poor and lacked a stable occupation, frequently suffered from job insecurity and unemployment. In order to survive, they took advantage of the seasonal, temporary or occasional work opportunities in the city and its rural surroundings (Martínez Martín, Martínez López and Moya García, 2014): peonage in construction, public works and urban reforms; working as temporary agricultural labourers at seasonal peaks of agricultural production; dockers in the bay of the railway station and as loaders in the central market, porters for hotels, inns and hostels in the city, errand runners for retail establishments and the businesses of the city, etc.

In short, the occupational structure of the male population was determined by the weight of the manual activity, generally in conditions of job insecurity. The temporary farmworkers and the day labourers accounted for 40 per cent of the male active population and represented 44.1 per cent of households with male breadwinners. The secondary sector, made up of self-employed manual workers and craft manufacturers or domestic workers accounted for a sizeable portion of the male active population.

Table 6. Distribution of the city’s population by sector of activity

|

PST type |

Total |

Men |

Women |

|||||||

|

% |

Nº |

% |

Nº |

% |

Nº |

|||||

|

Active population (15-65 years) |

||||||||||

|

Primary |

9.9 |

1,717 |

18.9 |

1,573 |

1.6 |

144 |

||||

|

Farmers and farm labourers |

1.5 |

268 |

1.8 |

150 |

1.3 |

118 |

||||

|

Temporary agricultural labourer |

7.4 |

1,283 |

15.3 |

1,269 |

0.3 |

25 |

||||

|

Others |

0.9 |

166 |

1.8 |

154 |

0.0 |

1 |

||||

|

Secondary |

8.9 |

1,548 |

16.7 |

1,389 |

1.8 |

159 |

||||

|

Building and construction |

3.5 |

611 |

7.3 |

610 |

0.0 |

1 |

||||

|

Construction |

2.3 |

397 |

4.8 |

397 |

0 |

0 |

||||

|

Clothing / Boots and Shoes / Textiles |

2.3 |

400 |

3.4 |

284 |

1.3 |

116 |

||||

|

Food industries |

0.7 |

133 |

0.1 |

10 |

0.0 |

10 |

||||

|

Others |

2.3 |

404 |

4.5 |

372 |

0.3 |

32 |

||||

|

Tertiary |

18.7 |

3,235 |

25.8 |

2,142 |

12.1 |

1,093 |

||||

|

Services and professions |

13.2 |

2,295 |

18.3 |

1,518 |

8.6 |

777 |

||||

|

Commercial and administrative services |

1.2 |

216 |

2.5 |

209 |

0.0 |

7 |

||||

|

Professions + Professions support |

2.2 |

383 |

4.2 |

349 |

0.3 |

34 |

||||

|

Local + National Government Services |

1.8 |

320 |

3.8 |

315 |

0.0 |

5 |

||||

|

Servants |

3.7 |

642 |

0.6 |

52 |

6.5 |

590 |

||||

|

Dealers + Sellers |

4.3 |

751 |

5.4 |

453 |

3.3 |

298 |

||||

|

Transport and Communications |

1.1 |

189 |

2.1 |

171 |

0.2 |

18 |

||||

|

Not specified |

12.2 |

2,113 |

24.9 |

2,065 |

0.5 |

48 |

||||

|

Day labourers |

11.6 |

2,017 |

24.8 |

2,061 |

0.5 |

46 |

||||

|

No job / not declared |

50.3 |

8,725 |

13.7 |

1,135 |

84.0 |

7,590 |

||||

|

Total |

100.0 |

17,338 |

100.0 |

8,304 |

100.0 |

9,034 |

||||

|

Households headed by active population (15-65 years) |

||||||||||

|

Primary |

17.1 |

1,080 |

20.8 |

1,074 |

0.5 |

6 |

||||

|

Farmers and farmworkers |

1.7 |

102 |

1.9 |

98 |

0.3 |

4 |

||||

|

Temporary farmworkers |

13.6 |

862 |

16.6 |

860 |

0.2 |

2 |

||||

|

Others |

1.8 |

116 |

2.2 |

116 |

0 |

0 |

||||

|

Secondary |

14.8 |

937 |

17.5 |

905 |

2.7 |

32 |

||||

|

Building and construction |

6.1 |

389 |

7.5 |

389 |

0 |

0 |

||||

|

Construction |

4.4 |

281 |

5.4 |

281 |

0 |

0 |

||||

|

Clothing / Boots and Shoes / Textiles |

3.4 |

217 |

3.7 |

194 |

1.9 |

23 |

||||

|

Food industries |

1.5 |

94 |

1.7 |

89 |

0.4 |

5 |

||||

|

Others |

3.7 |

237 |

4.5 |

233 |

0.3 |

4 |

||||

|

Tertiary |

27.9 |

1,764 |

30.1 |

1,555 |

17.9 |

209 |

||||

|

Services and professions |

20.4 |

1,295 |

21.7 |

1,122 |

14.8 |

173 |

||||

|

Commercial and administrative services |

2.3 |

145 |

2.8 |

144 |

0.0 |

1 |

||||

|

Professions + Professions support |

4.4 |

280 |

5.3 |

273 |

0.6 |

7 |

||||

|

Local + National Government Services |

4.1 |

260 |

5.0 |

257 |

0.2 |

3 |

||||

|

Servants |

1.8 |

114 |

0.3 |

15 |

8.5 |

99 |

||||

|

Dealers + Sellers |

5.2 |

333 |

5.8 |

301 |

2.7 |

32 |

||||

|

Transport and Communications |

2.1 |

136 |

2.7 |

142 |

0.3 |

4 |

||||

|

Not specified |

22.6 |

1,432 |

27.5 |

1,422 |

0.9 |

10 |

||||

|

Day labourers |

22.6 |

1,432 |

27.5 |

1,422 |

0.9 |

10 |

||||

|

No job / not declared |

17.7 |

1,119 |

4.1 |

211 |

77.9 |

908 |

||||

|

Total |

100.0 |

6,332 |

100.0 |

5,167 |

100.0 |

1,165 |

||||

Source: Census certificates of 1920.

The occupational structure of the female active population also determined the level of income of the female workers. The census information, subject to the under-recording of the activity of women, showed a very low female activity rate (Table 3).

The low female activity rate recorded reflects part of the labour reality of the city, given that the opportunities of formal and paid employment for women were curtailed by supply and demand. The women exclusively carried out domestic work and for no payment, basically sustaining the production of the population and the reproduction of the city’s workforce. This was a tremendous amount of work that consumed a large part of their energy and time, particularly in the case of married or widowed women or in the case of single women caring for dependent people, reducing their opportunities for being employed in paid jobs. On the other hand, in a labour market segmented by gender, the most stable and best paid occupations were masculinized. In addition, the industrial production that traditionally employed female labour, such as the textile industry, had a low presence in the city.

Nevertheless, the low female activity rate was principally the result of the under-recording of women’s jobs, particularly of those carried out by married women. Therefore, the reduced female activity reported in the census information prevented the full reconstruction of its volume, although this information does offer clues about the paid jobs that were offered to women and, as a result, it is possible to study the occupational structure of the female population.

According to the census information, the female workers in the city were mainly employed in services and trade, with the two sectors jointly accounting for 12.1% of the female active population and 17.9 per cent of female household heads. Among these workers, those in the home (“servants”) made up the most numerous occupation by far. The 590 servants registered represented 6.8 per cent of the total female active population. They were mainly single women and widows with no family responsibilities, who had time to engage themselves in such taxing work. Other women, mainly married women, carried out domestic services from their own homes (ironing, laundry, etc.). Sales and services in small retail establishments and family businesses and street sales also accounted for a sizeable group of female workers (3.3%).

The secondary and primary activities employed a very low number and proportion of female workers. Textile production (dressmakers and seamstresses), often carried out from their own homes, was the principal secondary activity. The active female workers in the primary sector were mainly farm owners, normally widows and temporary female farmworkers in the maximum peaks of the cereal harvest period or olive harvesting, when the male workforce was insufficient.

Domestic work and services, together with sales in retail establishments and in the street, were the activities that regularly employed the most women. These were jobs at the bottom of the income scale of the city’s population.

Income

The prevalence of manual male active workers and the abundance of unskilled workers (day labourers, temporary farmworkers, etc.), employed in activities with low productivity, pushed down the income of the population (Table 7).

The average daily income of manual workers (3.38), who represented more than two-thirds of the active male population and almost three-quarters of the male heads of household, drove down the average income of the whole of the male population /4.15 pesetas per day). The income of the few women with a recorded wage was even lower (1.24 pesetas per day) —almost three times less than the male wage—, a difference that was most acute among the manual female workers, whose income was one fifth of that of the male manual workers.

Table 7. Individual income and class. Daily average wage (in current pesetas) of the active population (15-65 years)

|

HISCLASS Social structure of the population |

Men |

Women |

||||||||

|

Social structure of the population |

Population with income |

Social structure of the population |

Population with income |

|||||||

|

% |

Nº |

Nº |

Income |

% |

Nº |

Nº |

Income |

|||

|

Non-manual occupations |

19.5 |

1,627 |

904 |

7.57 |

4.4 |

401 |

46 |

4.83 |

||

|

Manual occupations |

67.1 |

5,570 |

3,900 |

3.38 |

12.8 |

1,158 |

460 |

0.69 |

||

|

Skilled occupations (6 to 10) |

25.7 |

2,133 |

1,412 |

3.67 |

5.1 |

463 |

123 |

1.19 |

||

|

Unskilled (11-12) |

41.4 |

3,437 |

2,488 |

3.21 |

7.7 |

695 |

337 |

0.51 |

||

|

Male and female day labourers |

24.6 |

2,045 |

1,424 |

3.30 |

0.5 |

49 |

10 |

1.90 |

||

|

Field workers |

15.3 |

1,269 |

1,002 |

3.17 |

0.2 |

25 |

8 |

2.38 |

||

|

Servants |

0.6 |

52 |

27 |

0.87 |

6.5 |

594 |

318 |

0.42 |

||

|

Others |

0.8 |

71 |

35 |

2.19 |

0.2 |

27 |

1 |

1.64 |

||

|

No occupation / inactive |

13.3 |

1,107 |

49 |

3.01 |

82.8 |

7,476 |

77 |

2.38 |

||

|

Total |

100.0 |

8,304 |

4,853 |

4.15 |

100.0 |

9,034 |

583 |

1.24 |

||

Source: Census certificates of 1920

The individual income, in turn, reduced the family income (Table 8). The households with non-manual breadwinners had a low level of income (4.66 pesetas) which pushed down the family revenue of all of households with male breadwinners (5.54 pesetas). In turn, the income of households headed by male active workers was much higher than that of women (2.83 pesetas), although in this case the gender gap was lower than for individual income - the income of households with female breadwinners was half that of the male income-. The predominance of a single male income in households with male breadwinners, which represented 79.4% of the family income, as opposed to the greater frequency of double or more individual incomes recorded in female-headed households (Annexes G, H and I), explains this reduction in the gender gap between male-headed and female-headed households.

Table 8. Individual income and class. Daily average income (in current pesetas)

|

HISCLASS Social structure of household heads |

Households headed by men |

Households headed by women |

Households |

||||||||||||||

|

Social structure of household heads |

Breadwinners with income + other income |

Social structure of household heads |

Breadwinners with income + other income |

Social structure of household heads |

Breadwinners with income + other income |

||||||||||||

|

% |

Nº |

Nº |

Income |

I / PH |

% |

Nº |

Nº |

Income |

I / PH |

% |

Nº |

Nº |

Income |

I / PH |

|||

|

Non-manual occupations |

24.5 |

1,375 |

765 |

8.66 |

2.55 |

6.7 |

98 |

25 |

5.50 |

2.38 |

20.8 |

1,473 |

790 |

8.66 |

2.54 |

||

|

Manual occupations |

70.4 |

3,947 |

2,782 |

4.66 |

1.25 |

13.6 |

200 |

114 |

2.14 |

0.67 |

58.6 |

4,147 |

2,896 |

4.56 |

1.22 |

||

|

Skilled |

25.2 |

1,413 |

946 |

5.00 |

1.34 |

4.5 |

66 |

32 |

3.59 |

1.04 |

20.9 |

1,479 |

978 |

4.95 |

1.33 |

||

|

Unskilled |

45.2 |

2,534 |

1,836 |

4.48 |

1.20 |

9.1 |

133 |

82 |

1.57 |

0.53 |

37.7 |

2,667 |

1,918 |

4.36 |

1.17 |

||

|

Male and female day labourers |

27.1 |

1,521 |

1,040 |

4.57 |

1.25 |

0.6 |

9 |

2 |

3.94 |

0.93 |

21.6 |

1,529 |

1,042 |

4.57 |

1.24 |

||

|

Field workers |

16.7 |

935 |

756 |

4.34 |

1.14 |

0.2 |

3 |

1 |

0.95 |

0.47 |

13.2 |

938 |

757 |

4.34 |

1.14 |

||

|

Servants |

0.3 |

18 |

10 |

1.24 |

0.48 |

7.7 |

114 |

78 |

1.52 |

0.52 |

1.8 |

132 |

88 |

1.48 |

0.51 |

||

|

Others |

1.0 |

58 |

30 |

6.55 |

1.44 |

0.5 |

7 |

1 |

1.64 |

0.82 |

0.9 |

68 |

31 |

6.37 |

1.42 |

||

|

No occupation / inactive |

5.1 |

286 |

45 |

5.47 |

1.55 |

79.5 |

1,167 |

49 |

3.09 |

1.45 |

20.6 |

1,453 |

94 |

4.23 |

1.50 |

||

|

Total |

100.0 |

5,608 |

3,592 |

5.54 |

1.53 |

100.0 |

1,464 |

188 |

2.83 |

1.10 |

100.0 |

7,072 |

3,780 |

5.41 |

1.51 |

||

Source: Census certificates of 1920.

- The average family income of households with live-in servants is the result of adding together the income of all members of the family (without counting the live-in servants) and subtracting the income of the live-in servants.

- I / PH = Income by number of people in the household.

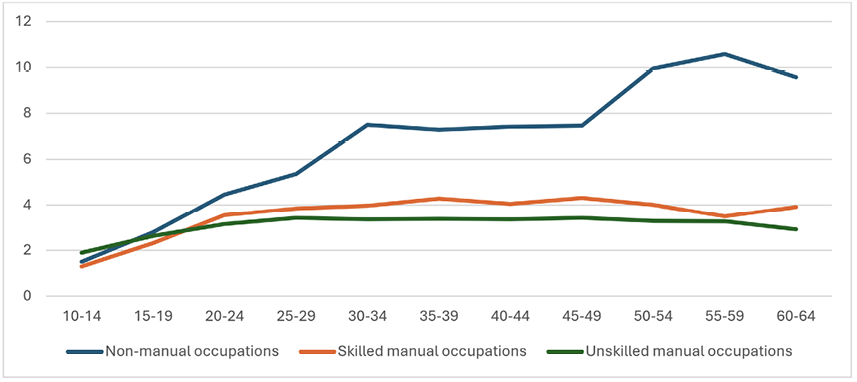

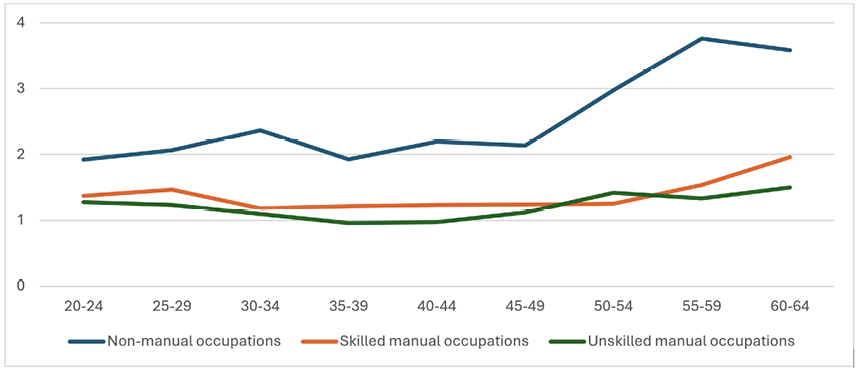

A very important characteristic of the income of manual active workers, who conditioned the level of income of the majority of the families in the city, was that it hardly fluctuated during their life course (Graph 3).

The income earned by non-manual workers evolved positively over their individual and family life courses: when they reached their twenties and got married and started to form a family with the birth of their first children, their income increased sharply; between their thirties and forties, as the families became complete, their income consolidated; between their fifties and sixties, at the end of their professional or business career, they earned their highest revenues, once again increasing their income considerably. In contrast, the evolution of the income of manual workers was almost flat; they began with a slight increase, coinciding with their incorporation into the labour market in their early twenties; from this age, when they got married and started to form a family, their income froze until their retirement.

Graph 3. Male income and life course

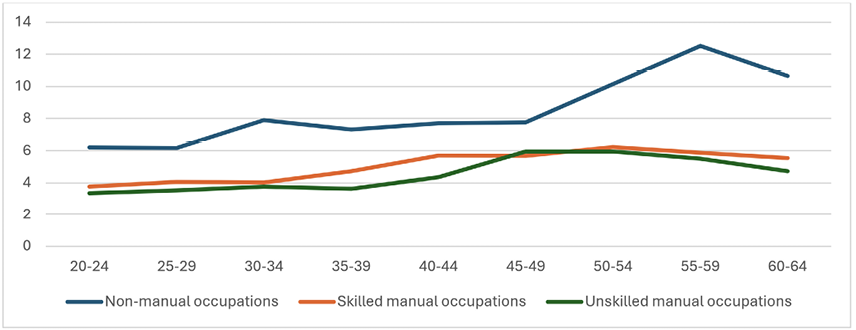

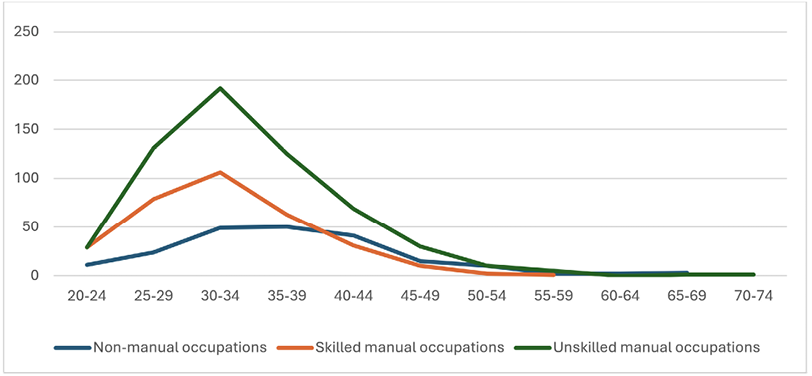

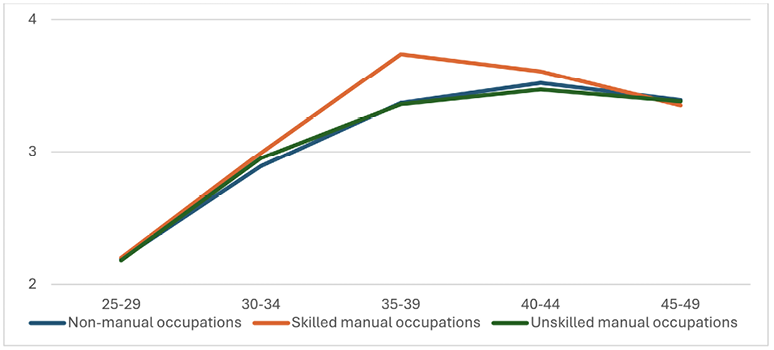

The evolution of the family income during the life course varied according to social class (Graphs 3 and 4). The evolution of the family income of households with non-manual breadwinners basically depended on the income of the head of the household (Annex G) and, therefore, it was similar to the evolution of the individual income of these workers: an increasing phase during their twenties, coinciding with the time they got married, a stage of stabilisation between their thirties and forties as they completed their families and a final phase of a sharp increase in income from their fifties, when the increase of the breadwinner’s income was complemented by the income of one or more of their adult children.

Graph 4. Household income and life cycle of breadwinner

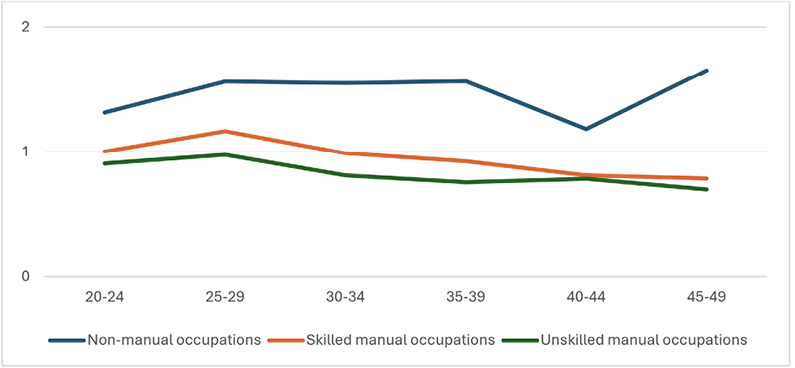

The evolution of the family income of the manual workers was different to that of the individual income (Graphs 3 and 4), because the contribution of other family members was fundamental for maintaining a minimum critical income. Therefore, when the breadwinners were in their late thirties and their families had been completed, the number of dependent people increased and the income per capita decreased (Graph 5), the older children, still in their youth, worked and contributed their wage to the family income, which increased and remained stable until the end of the family life course. This contribution to the composition of the family income came at a critical stage of the family life course, when the family had been completed and the number of dependent children increased, which, in fact, must have been greater than that reflected in the census records which should also have included the work and wages of the mothers and older daughters.

Graph 5. Income (per capita) of members of the household and life cycle of breadwinner

The evolution of the income of the 3B families with children under the age of 13, whose household budgets will be analysed in the following section, clearly shows the critical nature of this stage of the family life course of the manual workers’ households. These households, which, according to the census information, exclusively depended on the income of the adult male, experienced a sharp fall in income when the breadwinners reached their thirties and their families had been completed (Graphs 6, 7 and 8). As we shall see, this decrease placed great stress on the household budgets of the majority of the families.

Graph 6. Life cycle of heads of 3B households with children < 13 years old (total numbers)

Graph 7. Mean number of children and life cycle of heads of 3B households with children < 13 years old

Graph 8. Income (per capita) of members of the household and life cycle of the heads of 3B families with children < 13 years old

The household budget and the unlikely “breadwinner”

The balance of the household budgets constructed using the census information indicates that the income of nuclear families with dependent children, based almost exclusively on the income of the adult male, was insufficient (Tables 9 and 10).

87.2 per cent of the households of the city did not cover their domestic expenses (Table 9). Only families headed by non-manual workers, representing a quarter of all of the households in the city, had sufficient income to cover the domestic expenses; but even in this case, one third of them were far from being able to do so. Almost none of the families headed by manual workers, representing three quarters of the families, were able to balance the household budget; a situation that was particularly severe among the unskilled workers (day labourers, temporary agricultural labourers) and from which only 14.3 per cent of skilled manual workers (“working-class aristocracy”) were able to escape.

A very high proportion of the families of manual workers had a very low coverage of their domestic expenses (Tables 9 and 10) (half of that of families headed by skilled workers and 58.8 per cent of those with unskilled breadwinners did not reach a coverage of 60 per cent) and were unable to cover food expenses, which represented 78.3% of household expenses. As a result, they were unable to maintain a minimum standard of living. The acute budget stress of these families with dependent children could only be covered with the contribution of the income of other family members, basically the women.19 According to our estimates, without these contributions, which were not visible in the census information, the family budgets would have been insufficient. However, the opportunities for earning income, in kind or cash, of women in the city were limited.

Table 9. Coverage of domestic expenses of 3B households with children < 13 years (%)

|

HISCLASS |

> 60 |

60 – 79.9 |

80 – 99.9 |

=/>100 |

Total |

|||||||

|

% |

Nº |

% |

Nº |

% |

Nº |

% |

Nº |

% |

Total |

|||

|

Income of breadwinners |

||||||||||||

|

Non-manual occupations |

35.7 |

74 |

9.2 |

19 |

11.6 |

24 |

43.5 |

90 |

100 |

207 |

||

|

Manual occupations |

56.2 |

515 |

18.5 |

170 |

19.6 |

180 |

5.6 |

51 |

100 |

916 |

||

|

Skilled |

51.2 |

165 |

10.2 |

33 |

25.1 |

81 |

13.3 |

43 |

100 |

322 |

||

|

Unskilled |

58.8 |

350 |

23.1 |

137 |

16.6 |

99 |

1.3 |

8 |

100 |

594 |

||

|

Male and female day labourers |

63.2 |

203 |

20.5 |

66 |

15.2 |

49 |

0.9 |

3 |

100 |

321 |

||

|

Field workers |

60.7 |

159 |

18.3 |

48 |

19.1 |

50 |

1.9 |

5 |

100 |

262 |

||

|

Servants |

50.0 |

2 |

25.0 |

1 |

25.0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

100 |

4 |

||

|

Others |

57.1 |

4 |

14.3 |

1 |

28.5 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

100 |

7 |

||

|

No occupation / inactive |

50.0 |

2 |

25.0 |

1 |

25.0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

100 |

4 |

||

|

Total |

52.6 |

593 |

16.8 |

189 |

18.1 |

204 |

12.5 |

141 |

100 |

1,127 |

||

|

Family income (breadwinner’s income + other incomes) |

||||||||||||

|

Non-manual occupations |

32.8 |

68 |

12.5 |

26 |

11.6 |

24 |

43.0 |

89 |

100 |

207 |

||

|

Manual occupations |

56.1 |

514 |

18.6 |

171 |

19.1 |

175 |

6.1 |

56 |

100 |

916 |

||

|

Skilled |

50.6 |

163 |

17.7 |

57 |

17.4 |

56 |

14.0 |

46 |

100 |

322 |

||

|

Unskilled |

58.4 |

347 |

16.1 |

96 |

23.7 |

141 |

1.7 |

10 |

100 |

594 |

||

|

Male and female day labourers |

58.7 |

189 |

16.4 |

53 |

23.6 |

76 |

1.8 |

4 |

100 |

321 |

||

|

Field workers |

54.2 |

142 |

18.7 |

49 |

24.8 |

65 |

2.3 |

6 |

100 |

262 |

||

|

Servants |

50.0 |

2 |

25.0 |

1 |

25.0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

100 |

4 |

||

|

Others |

71.4 |

5 |

14.3 |

1 |

14.3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

100 |

7 |

||

|

No occupation / inactive |

50.0 |

2 |

25.0 |

1 |

25.0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

100 |

4 |

||

|

Total |

51.8 |

584 |

17.5 |

198 |

17.7 |

200 |

12.8 |

145 |

100 |

1,127 |

||

Source: Census certificates of 1920

Domestic production and the communal economy were non-commercial ways of provisioning and domestic self-consumption. They were characteristic of the rural populations in Andalusia until the end of the nineteenth century and fundamentally based on female and child labour. However, they played a marginal role in the subsistence of the urban population. Only a small proportion of the agricultural workers of the city, the market gardeners who worked the land surrounding it to the west, were able to achieve this through the self-consumption of proteins and vitamins in the form of the meat, milk and fruit and vegetables that they produced. The mountains to the south of the city, which were privatised, could not be communally exploited and this practice was not viable (except during the brief regulated periods of foraging) in the large agricultural area of the municipality dedicated to cereal and olive crops.

The majority of the manual workers, with no property or capital, could only earn income in the labour market, generally in informal activities at the bottom rungs of the wage ladder. Working as a servant or sales assistant in local retail establishments, which were some of the principal occupations that were registered in the census, was incompatible with the domestic work and caring for dependent children that married women carried out in their homes. These women were mainly employed in activities that they could do in their homes, such as domestic services (ironing, laundry, etc.) and sewing and clothes repair (dressmakers and seamstresses); or in activities such as street sales, compatible with being accompanied by their children. And at times of peak demand for agricultural labour, during the reaping of the cereal or harvest of the olives, they could also be employed as temporary farmworkers (Benítez Porral, 1904), although this meant taking their children to the fields or leaving the elder daughters to take care of the rest of their siblings, leading to a high rate of school absenteeism, which particularly affected the girls (Borrás Llop, 1996).

The description that Luis Bello (2007) made at the end of the 1920s of the situation of the children in the schools of the city of Jaén is highly illustrative:

“(Original citation in italics) —What is your father? What does he work as? - He’s a bricklayer, a miller. Today he has gone to the fields. To work. In the olive groves. To the shop. He is unemployed… All of them are poor. Very rarely are they the sons of property owners, they are day labourers (...). The schools may be different but the children sitting on their benches have a common denominator: poverty. —Public school, school for the poor!— (…) They are poor, they are humbly dressed! (…). They work hard, God and the teacher know. They have their pages, their notebooks, their slates; their timetables and regime... Like everywhere. The result...their parents take the children away very early... It is best to enrol them before they do in other places. When they leave school, the majority of these kids have hardly begun to awaken. Being a village of agricultural labourers, the soil will soon call them, which, as you will see, buries them twice.”

Table 10. Balance of the household budget (in current pesetas) of the 3B households with children < 13 years

|

HISCLASS |

With the breadwinner’s income |

With the family income |

||||||

|

Income |

Expenditure |

Balance |

Income |

Expenditure |

Balance |

|||

|

Non-manual occupations |

6.83 |

6.11 |

+ 0.72 |

6.89 |

6.11 |

+ 0.78 |

||

|

Manual occupations |

3.58 |

5.99 |

- 2.40 |

3.62 |

5.99 |

- 2.36 |

||

|

Skilled |

3.98 |

5.97 |

- 1.98 |

4.02 |

5.97 |

- 1.94 |

||

|

Unskilled |

3.37 |

6.00 |

- 2.63 |

3.41 |

6.00 |

- 2.59 |

||

|

Male and female day labourers |

3.45 |

5.99 |

- 2.54 |

3.49 |

5.99 |

- 2.50 |

||

|

Field workers |

3.32 |

6.00 |

- 2.68 |

3.37 |

6.00 |

- 2.63 |

||

|

Servants |

1.46 |

5.84 |

- 4.38 |

1.46 |

5.84 |

- 4.38 |

||

|

Others |

2.16 |

6.02 |

- 3.85 |

2.16 |

6.02 |

- 3.85 |

||

|

No occupation / inactive |

3.37 |

6.10 |

- 2.72 |

3.53 |

6.10 |

- 2.57 |

||

|

Total |

4.18 |

6.01 |

- 1.83 |

4.22 |

6.01 |

- 1.79 |

||

|

Mean coverage of the household budget of 3B households with children < 13 years (%) |

||||||||

|

HISCLASS |

With the breadwinner’s income |

With the family income |

||||||

|

Non-manual occupations |

111.78 |

112.76 |

||||||

|

Manual occupations |

59.76 |

60.43 |

||||||

|

Skilled |

66.66 |

67.33 |

||||||

|

Unskilled |

56.16 |

56.83 |

||||||

|

Male and female day labourers |

57.59 |

58.26 |

||||||

|

Field workers |

55.33 |

56.16 |

||||||

|

Servants |

25.00 |

25.00 |

||||||

|

Others |

35.88 |

35.88 |

||||||

|

No occupation / inactive |

55.24 |

57.86 |

||||||

|

Total |

69.55 |

70.21 |

||||||

Source: Census certificates of 1920; Annex E.

Without the contribution of the income derived from the women’s work, the household budgets of the manual workers’ families with dependent children would have been unviable. Therefore, as shown in the balance of the simulated household budgets (Table 11) with the mean income of a worker in the active age bracket (Table 7), even with the contribution of the women to the family income, the household budgets continued to be deficient, particularly those of the families of unskilled manual workers.

In these conditions, at least among the poorest families, child labour or the search for income through marginal activities must have been commonplace. In order to combat food poverty, women could resort to family solidarity or, in desperate situations, public or private charities and begging; and men to petty theft and other forms of minor delinquency to compensate food and energy poverty. Also frequent was the non-payment of rent, which took second place to food in the household budget priorities, with the resulting risk of eviction. The pawning of valuable objects or the accumulation of debt also formed part of this repertoire of strategies used to face critical situations.

TABLE 11. Simulation (with a universal income of the women) of the balance of the household budget (in current pesetas) of the 3B households with children < 13 years

Conclusions

At the beginning of the twentieth century, subsistence in the city of Jaén depended on the markets. The consumption of food, energy (firewood, coal, etc.), goods (clothes, medicines, etc.) and services (housing, healthcare, etc.) necessary for the reproduction of the population was mainly derived from the markets of the city and surrounding area. Income, in the form of wages or rent, was also derived mainly from the sale of labour, products and services.

Therefore, the limited employment and income opportunities in the city negatively conditioned the subsistence of the majority of the population. With a lean and traditional production fabric and a discreet demographic growth, the weak economy of the city was based on its functions as a provincial capital and the trade, business and production that responded to the demands of its population and that of its rural hinterland.

The population was employed in the sales and services activities of the small shops and family businesses, in the production generated by craft workshops, the construction and repair of housing, domestic service and seasonally in agricultural work. The weak production fabric, the traditional nature of trade and services and the predominance of labour-intensive activities, such as bricklaying or agricultural work, subject to a high degree of seasonality, together with an abundant and flexible labour supply, pushed down the wage level and the income of the majority of the population.

The inflationary spiral and the shortage of supplies during the years of the First World War severely damaged the purchasing power of families. The wage increase achieved by the workers’ mobilisation (Garrido, 2022) tempered the impact of inflation on the city, although in 1920, the majority of the population were immersed in poverty.

An analysis of the household budgets of the nuclear families with dependent children shows that in 1920 “the male family wage” was the reality of only a very small minority of families, those headed by non-manual workers with a higher level of wealth (capital and/or rent), the families of the large farm owners and businessmen and the families of liberal professionals and high ranking officials of the administration. The single income of the adult male was insufficient to maintain a large proportion of the families of non-manual workers, those of the lower middle class, which had deficit balances in their household budgets. The majority of families headed by manual workers, even those of the “working-class aristocracy” (skilled manual workers), not only had negative balances but also a very low level of coverage of their household budget, which was incompatible with the living conditions necessary for production and social reproduction.

The results of our research are much more severe than those obtained by Luis Garrido based on the analysis of food expenditure, who maintains that the “breadwinner” model could prevail among the middle classes and even among the “working-class aristocracy”20; our results indicate that the skilled workers could not generally sustain their families alone and that even a segment of the non-manual workers encountered serious difficulties to do so. They coincide greatly with the conclusions obtained by Carlos Arenas (1992), based on the study of working-class families of the city of Seville, who maintains that poverty not only affected the families of the day labourers but also those of many skilled manual workers.

In these circumstances, the contribution to the family income of paid work by the adult women and even that of some of the older children (10, 11 or 12 years) played a complementary role in the formation of the household budget. These contributions that were not generally recorded in the census documents but are testified by the qualitative studies on women’s labour and the child population (Garrido, 1990; Borrás Llop, 2015) and suggested by the photographic images and journalistic descriptions and literary stories of the period (Benítez, 1904; Albuera, 2006; Bello, 2007).

The budget deficit of the majority of families reached such a high level that even with the female income (as shown in the simulation exercise of constructing budgets with the universal contribution of both spouses (Table 11)), the budgets of the unskilled manual workers’ families (day labourers and temporary farmworkers) continued to be insufficient. In these conditions, many of these families, which formed the majority part of the popular classes of Jaén, often resorted to alternative or marginal survival strategies.

The family, friend and neighbour support networks were the first point to which families in critical situations of poverty turned to source food or other basic necessity goods. Another common recourse was the relief of the public institutions (local government, schools, etc.) in the form of the provision of bread or breakfast in schools. Private charity, through testamentary dispositions of the richest classes (bourgeoisie and upper middle class), also distributed bread or small money donations. The accumulation of debt in shops, the late payment or the non-payment of rent were also practices in this repertoire of minimum subsistence. In the most extreme cases, people resorted to begging or delinquency, such as the theft of food or clothes.

However, the analysis of the formation of household budgets reveals that the inequality prevailing in Jaén society was not only conditioned by the class position of individuals and family and was not only related to the contrast between the wealth and power of owners, businessmen and professionals and the poverty of manual labour or the hardships of the lower middle class, but also affected the gender relations that organised reproduction from the family and production from the market. These relations were eminently uneven, rooted in the sexual division of labour, which foisted a double load of work onto the women, the unpaid domestic work and paid work. Without this double labour effort or this double working day, the subsistence of the working-class families would have been unfeasible.

The analysis of the household budgets of nuclear families with children under the age of thirteen indicates that the standard of living of the population of the city in 1920, similarly to the case of other Andalusian cities (Arenas, 1992; Calero Amor, 1973), was extraordinarily low, lower than at the end of the 1800s or the first decade of the 1900s.

In light of this reality, it is difficult to ignore that the popular mobilisation of the so-called “Bolshevik Triennium” in defending the restoration of a minimum standard of living and fundamentally manifested in the demand for bread and work and the control of the shortages and prices of food and rent and aimed against the corruption and negligent spending of the municipal and central authorities, was based on objective material motivations. The structural problems of the urban society of Jaén, Andalusia and Spain (Otero Carvajal and Martínez López, 2022), such as the scourge of unemployment, the shortage of essential goods and housing, which were aggravated with the inflationary crisis caused by the First World War, condemned the majority of the families in the city to poverty.

Undoubtedly, the construction by the republican and socialist avant-garde of an egalitarian and democratic vindictive imaginary was based on the impetus that proletarian internationalism gave to the creation of resistance, mutual aid and union workers’ organisations, the creation of an emancipating and egalitarian reality and to the refining of an experience of cooperation and collective action. However, and analogous to what came to pass in other situations of emancipating and democratic collective mobilisation in European societies in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the structure of opportunity of the collective action of the “Bolshevik Triennium” was framed within a situation of collective material suffering caused by a recurring crisis as a result of capitalism.

Sources

Anuario Estadístico de España, 1920.

Cédulas del padrón de habitantes de Jaén, 1920. Archivo Histórico Municipal de Jaén.

“Pliego de condiciones para optar a la subasta de suministros de víveres y combustibles necesarios para el abasto, durante el año económico de 1920 a 1921 de los tres establecimientos de beneficencia de la capital de Jaén”, Boletín Oficial de la Provincia de Jaén, 27 March 1920.

Estadística de salarios y jornadas de trabajo referida al período 1914-1925, Madrid, Ministerio de Trabajo, 1927.

Bibliography

ALBUERA, A. (2006): El mundo del trabajo en Andalucía visto por los escritores (1875-1931). Málaga: University of Malaga.

ARENAS POSADAS, C. (1992): La Sevilla inerme: un estudio sobre las condiciones de vida de las clases populares sevillanas a comienzos del siglo XX (1883-1923). Écija, Gráficas Sol.

BELLO, L. (2007): Viaje por las escuelas de Andalucía (1926-1929). Sevilla, Centro de Estudios Andaluces y Editorial Renacimiento.

BORRÁS LLOP, J, M. (1996): “Zagales, pinches y gamenes… Aproximaciones al trabajo infantil”, in J. M. Borrás Llop (dir.), Historia de la infancia en la España contemporánea, 1834-1936. Madrid, Ministerio de Asuntos Sociales, pp. 229-346.

BORRÁS LLOP, J. M. (2015): “El trabajo infantil en España. Las aportaciones de la infancia a la subsistencia familiar”, in J. M. Borrás Llop, El trabajo infantil en España, 1700-1950. Barcelona, Icaria y Publicacions i edicions de la Universitat de Barcelona.

BENÍTEZ PORRAL, C. (1904): “El problema agrario en el Mediodía de España: conclusiones para armonizar los intereses de propietarios y obreros: medios de aumentar la producción del suelo”, A report that was runner-up in a competition opened by His Majesty the King and the Institute of Social Reforms.

BENÍTEZ PORRAL, C. (1911): Trabajos realizados por la Granja-Escuela Práctica de Agricultura Regional de Jaén, Dirección General de Agricultura. Minas y Montes, Madrid, Ministerio de Fomento.

BORDERÍAS, C. and MUÑOZ-ABELEDO, L. (2018): “¿Quién llevaba el pan a casa en la España de 1924? ¿Trabajo y economías familiares de jornaleros y pescadores en Cataluña y Galicia?”, Revista de Industria Industrial, 74, Año XXVII, pp. 77-106.

BORDERÍAS MONDÉJAR, C., MUÑOZ ABELEDO, L. and CUSSÓ i SEGURA, X. (2022): “Ganadores de pan en las ciudades españolas (1914-1930)”, Revista de Historia Industrial, 31, pp. 59-98.

CALERO AMOR (1973): Historia del movimiento obrero de Granada (1909-1923). Madrid, Editorial Tecnos.

CAMPOS LUQUE, C. (2012): “Teorías y realidad laboral de las mujeres en Andalucía”, in M.D. Ramos Palomo (coord.), Andalucía en la historia. Reflexiones sobre política, trabajo y acción colectiva. Centro de Estudios Andaluces, Consejería de la Presidencia e Igualdad, Junta de Andalucía.

GÁLVEZ MUÑOZ, L. (2008): Estadísticas Históricas del Mercado de Trabajo en Andalucía, Siglo XX. Sevilla, Instituto de Estadística de Andalucía.

GARRIDO GONZÁLEZ, L. (1990a): Riqueza y tragedia social. Historia de la clase obrera en la provincia de Jaén (1820-1939). Jaén, Diputación Provincial de Jaén, Tomo I.

GARRIDO GONZÁLEZ, L. (1990b): Riqueza y tragedia social. Historia de la clase obrera en la provincia de Jaén (1820-1939). Jaén, Diputación Provincial de Jaén, Tomo II.

GARRIDO-GONZÁLEZ, L. (2022): “Espacio urbano, movilización política democratizadora y conflicto social en el Jaén del primer tercio del siglo XX”, in L. E. Otero Carvajal and D. Martínez López, Entre huelgas y motines. Sociedad urbana y conflicto social en España, 1890-1936. Granada, Editorial Comares, pp. 283-306.

HERNÁNDEZ ARMENTEROS, S. (2000): “Jaén (1875-1930). Una sociedad en cambio”, in Jaén entre dos siglos (1875-1931). Catálogo 135 de la Colección Artistas Plásticos.

JANSSENS, A. (2004): “Transformación económica, trabajo femenino y vida familiar”, in D. I. Kertzer and M- Barbagli (comps.), La vida familiar en el siglo XX. Barcelona, Ediciones Paidós, pp. 115.179.

MALUQUER, J. (2013): “La inflación en España. Un índice de precios de consumo, 1830-2012”, Estudios de Historia Económica, 64.

MARTÍNEZ LÓPEZ, D., MARTÍNEZ MARTÍN, M. and MOYA GARCÍA, G. (2022): “Clase, género y capital educativo. La transición de la alfabetización en la Andalucía urbana, 1900-1930”, in L. E. Otero Carvajal and S. de Miguel Salanova (ed.), La educación en España. El salto adelante, 1900-1936. Madrid, Los Libros de La Catarata, 2022, pp. 215-227.

MARTÍNEZ MARTÍN, M., MARTÍNEZ LÓPEZ, D. and MOYA GARCÍA, G. (2014): “Estructura ocupacional y cambio urbano en la Andalucía oriental del primer tercio del siglo XX”, Revista de Demografía Histórica, XXXII-1, pp. 77-101.

MARTÍNEZ LÓPEZ, D. and SÁNCHEZ-MONTES GONZÁLEZ, F. (2008): “Familias y hogares en Andalucía”, in F. García González (coord.), Historia de la familia en la Península Ibérica: balance regional y perspectivas: Homenaje a Peter Laslett, Editorial , pp. 233-260.

MOYA GARCÍA, G. and MARTÍNEZ MARTÍN, M. (2013): “El trabajo femenino en la ciudad de Granada en 1921. Una reconstrucción desde los padrones municipales y desde los presupuestos de vida”, in M.A. del Arco, A. Ortega and M. Martínez (eds.), Ciudad y modernización en España y México, Universidad de Granada, pp. 495-509.

OTERO CARVAJAL, L. E. and MARTÍNEZ LÓPEZ, D. (2022): Entre huelgas y motines. Sociedad urbana y conflicto social en España, 1890-1936. Granada, Editorial Comares.

SAGRISTÁ, J. (1920): “La Internacional” el 27 de agosto de 1920. Cited by M. Tuñón de Lara (1978), Luchas obreras y campesinas en la Andalucía del siglo XX.

TIANA FERRER, A. (1987): “Educación obligatoria, asistencia escolar y trabajo infantil en España en el primer tercio del siglo XX”, in Historia de la educación: revista interuniversitaria, 6, pp. 43-59.

TUÑÓN DE LARA, M. (1978): Luchas obreras y campesinas en la Andalucía del siglo XX. Jaén (1917-20) y Sevilla (1930-1932). Madrid, Editorial Siglo XXI.

VIÑAO FRAGO, A. (2002): “Tiempos Familiares, Tiempos Escolares (Trabajo Infantil y Asistencia Escolar en España durante la segunda mitad del Siglo XIX y el primer tercio del siglo XX)”, in J. L. Guereña (ed.), Famille et éducation en Espagne et en Amerique Latine. Tours, Publications de l´Université de Tous, pp. 83-97.

VAN LEEUWEN, M. H. D. & MAAS, I. (2011): A historical international social class scheme. Leuven, Leuven University Press.

WRIGLEY, E. A., The PST system of classifying occupations.

Annex A. Price of the daily wage of some occupations in the city of Jaén (1920). In current pesetas/day

|

Census certificates |

Wage and working days statistics |

Statistical Yearbook of Spain |

|

|

(Number of cases) Mean daily wage |

Daily wage per working day of 8 hours |

Minimum daily wage |

|

|

Bricklayers |

(355) 5.0 |

5.3 |

7.5 |

|

Temporary farmworker |

(1,144) 4.6 |

-- |

6.0 |

|

Carpenters |

(163) 4.1 |

8.0 |

6.0 |

|

Seamstresses and dressmakers |

(61) 1.5 |

1.6 |

1.5 |

|

1.7 |

|||

|

Day labourers |

(1,580) 4.8 |

-- |

6.0 |

|

Shoemakers |

(117) 3.3 |

3.5 |

3.0 |

Source: Census certificates drawn from the Municipal Enumerator Books of Jaén, 1920; Ministerio de Trabajo, Estadística de salarios y jornadas de trabajo referida al período 1914-1925, Madrid, 1927; Anuario Estadístico de España, 1920.

Annex B. Income registration (in current pesetas) among the population of 15-65 years

|

HISCLASS |

Men |

Women |

||||||

|

Daily wage |

Monthly |

Annual |

Daily wage |

Monthly |

Annual |

|||

|

Non-manual occupations |

28.9 |

4.2 |

66.9 |

34.8 |

-- |

56.5 |

||

|