Wages and family strategies in Spanish mining in the 1920s. Río Tinto

Eva María Trescastro-López, University of Alicante

Ángel Pascual Martínez Soto, University of Murcia

Miguel Á. Pérez de Perceval, University of Murcia

Abstract

This article studies family income and household consumption in a specific mining area in southwest Spain (Nerva, province of Huelva), dependent on the British company Rio Tinto Mining Co Ltd. (RTCL) The data from the 1924 Municipal Population Register has been used as the basis for the analysis, which, exceptionally, offers the novelty of the trades and wage income declared by the men and women who made up the households in the town. We have been able to strengthen the work of reconstructing monetary income and household consumption with the rich documentation available (social, labour and economic) from the RTCL, which gives greater robustness to the results presented. Finally, the results of household food consumption clarify the problems faced by families in the mining area to achieve a minimum of biological well-being.

Keywords: Family composition, occupations of the registered population, household wage income, family consumption capacity, biological well-being.

Salarios y estrategias familiares en la minería española en los años veinte: Río Tinto

Resumen

El artículo realiza un estudio sobre las rentas monetarias familiares y el consumo de los hogares de una zona específicamente minera del Suroeste de España (Nerva, provincia de Huelva), dependiente de la empresa británica Rio Tinto Mining Co. Ltd. (RTCL). Se ha utilizado como base del análisis los datos del Padrón Municipal de Población de 1924 que, excepcionalmente, ofrece la novedad de los oficios e ingresos salariales declarados por los hombres y mujeres que conformaban los hogares de la localidad. Hemos podido robustecer el trabajo de reconstrucción de renta monetaria y consumo familiar con la rica documentación disponible (social, laboral y económica) de RTCL lo que le da mayor robustez a los resultados que se presentan. Finalmente, los resultados del consumo alimentario de las familias clarifica la problemática a la que se enfrentaban las familias de la zona minera para lograr un mínimo de bienestar biológico.

Palabras clave: Composición de las familias, oficios de la población censada, ingresos salariales de las unidades familiares, capacidad de consumo familiar, bienestar biológico.

Original reception date: October 25, 2024; final version: December 15, 2024.

- Eva María Trescastro-López, University of Alicante. Departament of Nursing; Balmis Research Group in History of Science, Health Care and Food; Research Group on Applied Dietetics, Nutrition and Body Composition; ISABIAL, Group 23. E-mail: eva.trescastro@ua.es;

ORCID ID: https://orcid. org/0000-0001-8378-1612

- Ángel Pascual Martínez Soto, University of Murcia. Facultad de Economía y Empresa, Campus de Espinardo s/n, 30100. Murcia. E-mail: apascual@um.es; ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4257-454X.

- Miguel Á. Pérez de Perceval, University of Murcia. Facultad de Economía y Empresa, Campus de Espinardo s/n, 30100. Murcia. E-mail: perceval@um.es; ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7051-3387.

Wages and family strategies in Spanish mining in the 1920s. Río Tinto

Eva María Trescastro-López, University of Alicante

Ángel Pascual Martínez Soto, University of Murcia

Miguel Á. Pérez de Perceval, University of Murcia

1. Introduction

This study analyses a population nucleus related to traditional mining1. Therefore, its characteristics are determined by the specificities of this industry. Mining was the principal occupation and structured the whole of the economic activity, determining the configuration of the territory. As indicated in other texts, the use of underground resources has specific connotations, being subordinate to non-renewable resources and international markets characterised by a certain degree of instability. At that time, mining used an abundant workforce and depended on a labour market that usually had to develop and organise itself in accordance with a series of specific needs. This was evident in the evolution of the population nuclei existing or developing around the mines. Naturally, all of this was connected to many more variables related both to resource endowment and the business characteristics. In this case, the activity was concerned with the mining of deposits of the Iberian Pyrite Belt2 by a large company, the Rio Tinto Co. Ltd. (Hereafter, RTCL), the largest mining company in the peninsula of the period3. In 1873, it acquired the mines from the State with very special conditions4. The number of people employed directly grew to over sixteen thousand people at the beginning of the twentieth century and fluctuated depending on the economic situation, as we shall see later. The municipalities in the basin increased their population and new ones formed. Nerva particularly stands out. It was the largest and concentrated a considerable part of the workforce of RTCL.

This article is based on the municipal register of inhabitants of 1924, due to the unique information that it provides on wages and rents, which (despite its drawbacks, which we will analyse further on) enables us to learn about the family budgets. However, this source is a snapshot in time, which has the problem that it only provides the information on family incomes for that particular year. This hinders the view of the evolution over a period and does not allow us to correct the influence of the economic situation. In any case, in this mining area, there is a considerable amount of documentation available of the company itself that can help, at least partly, to mitigate these shortcomings. From 1919, RTCL conducted a detailed study of the family organisation of the company’s workers, calculating the average incomes, the necessary family consumption and the minimum expenditure for a family of five members. We have focused on the municipal register of Nerva due to its importance in the mining basin and the availability of the documentation, unlike the municipal funds of Minas de Riotinto, which, due to different reasons, have been lost for this period.

The study begins with a description of the evolution of the municipalities that make up the mining area, particularly Nerva, which was the town with the largest number of inhabitants. Second, we analyse the social and wage policy of the company, highlighting the economic climate in the basin in 1924. Third, we describe the family organisation and income, highlighting the problems of the municipal register of 1924. Next, the diet of the mining population is studied through the analysis of the consumption of different types of families obtained from the study of the municipal register of inhabitants of 1924 in relation to the family income of each of them. The final section presents the principal conclusions of the study.

2. Nerva as a mining town

Between 1857 and 1930, the mining basin of Río Tinto was formed by three municipalities, two of which had been disjoined from the town of Zalamea la Real. The first was Minas de Riotinto in 1841 and the second Nerva in 1885. In 1931, a new town was created, El Campillo.

The first reference to the population nucleus of Nerva can be found in the Gazetteer of 1873 where it appears as a hamlet belonging to the municipality of Zalamea la Real, under the name of “Aldea de Río Tinto”, located 8.3 kilometres away from Zalamea and with a total population of 685 inhabitants. In the population census of 1887, it appears as an independent municipality with 6,431 inhabitants (3,636 men and 2,795 women). Between the Gazetteer of 1873 and that of 1888, the new municipality had grown from 137 buildings to 1,221 and its population had increased almost tenfold. The enormous influx of migrants was noteworthy, as was the high percentage of male population and the existence of 1,896 transient (unregistered) males, accounting for 52% of the male population, and a total of 1,275 women who were not registered (45% of the female population):

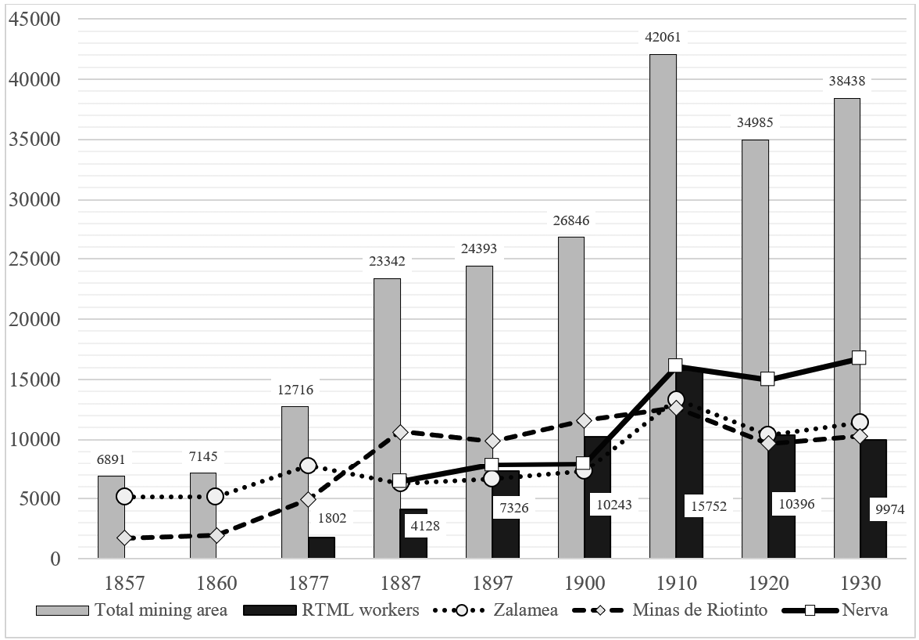

The nine population censuses that we have used show a rapid growth of the population, peaking in the basin in 1910 and in the municipality with the highest population, Nerva, in 1930, after which a decline in the population of the mining area as a whole began (Figure 1). The parallel movement of the population in all of the mining towns is noteworthy. They all grew and all shrank at the same time, although the level of population loss was not the same. Zalamea was the municipality that lost the most population, given that the rest of the towns of the mining district had been disjoined from it.

The growth of the population of the mining area was conditioned by the evolution of the workforce of RTCL. The greatest demographic expansion was recorded in the census of 1910 with the striking fact that Nerva significantly exceeded the other two municipalities, with all three having over 12,000 inhabitants. This situation is related to the opening of the so-called Corta Atalay in 1907, the largest open sky mine in the country, which attracted a large flow of labour. The workforce of RTCL reached 16,465 in 1908.

The evolution of the population of Nerva between 1873 and 1930 was, in general, similar to the rest of the municipalities making up the mining area, but specific characteristics that we will refer to later converted it into the municipality that became the social hub of this area. Nerva, behaved as a mining camp, where workers from different places around the country arrived in search of work. This situation was mediated by the evolution of the company’s recruitment process. In the whole period, it had a large floating population that entered and exited the municipality and which was difficult to control. In the census of 1910, the difference between the de facto and de jure population reached the figure of 4,260 inhabitants, the majority men (2,575). These data show that many of these men arrived in the municipality without a family and had the possibility of returning to their place of origin if they did not find work. Therefore, the difference between men and women in the de jure population was 1,059 in favour of the former, which shows the relevance of the number of men who were alone in 1910 residing in the town (Table 1). The population of Nerva continued to grow until it peaked in 1930 and from then it began a continuous decline.

Figure 1. Population of the mining district, 1857-1930

Source: Population censuses of Spain and the Historical Mining Archive of the Fundación Río Tinto (hereafter, AHMFRT), files 1805 and 1811.

The greatest growth in its population occurred between 1900 and 1910, an inter-census period in which the number of inhabitants grew from 1,908 to 16,087, which represents an increase of 103.4%, converting it into the most populated municipality of the mining area. This increase was due to different correlated factors5: the development of new mines known as Corta Atalaya and the three Cortas del Filón Norte, together with the activation of the Peña del Hierro mine in the municipality of Nerva; the large number of private homes existing in the town, which were not controlled by RTCL, generating a certain level of freedom among the miners; the abundance of services unconnected to RTCL (retail establishments, guest houses, brothels, etc.); the presence of the Minero-UGT Union, which, since the failed strike in 1913 abandoned its offices in Minas de Riotinto and established itself in Nerva in 1915 in order to distance itself from the surveillance of RTCL; and the subsidence in the village of Minas de Riotinto in 1908, which led some owners to sell their homes to the Company and move to Nerva where there was land and buildings available that were not controlled by RTCL. Workers who were dismissed or who retired also moved to Nerva as they had to leave the houses that RTCL had provided them. The strikes and labour conflicts between 1913 and 1921 gave rise to the dismissal of countless workers, who were immediately evicted from the houses that they occupied if they were owned by RTCL and were obliged to move to Nerva for the same reasons, together with the fact that Zalamea was very far from the mines and Minas de Riotinto was practically owned by the company.

Table 1. Difference in the growth of the three municipalities, 1920-1930.

|

Municipality |

Vegetative growth 1 |

Immigrants 2 |

(1 + 2) 3 |

Census difference 1930-1920 4 |

|

Zalamea |

696 |

912 |

1,608 |

1,074 |

|

Riotinto |

946 |

926 |

1,872 |

625 |

|

Nerva |

1,722 |

1,259 |

2,981 |

1,304 |

|

Total |

3,364 |

3,097 |

6,461 |

3,003 |

Source: Population censuses of Spain of 1920 and 1930. Province of Huelva.

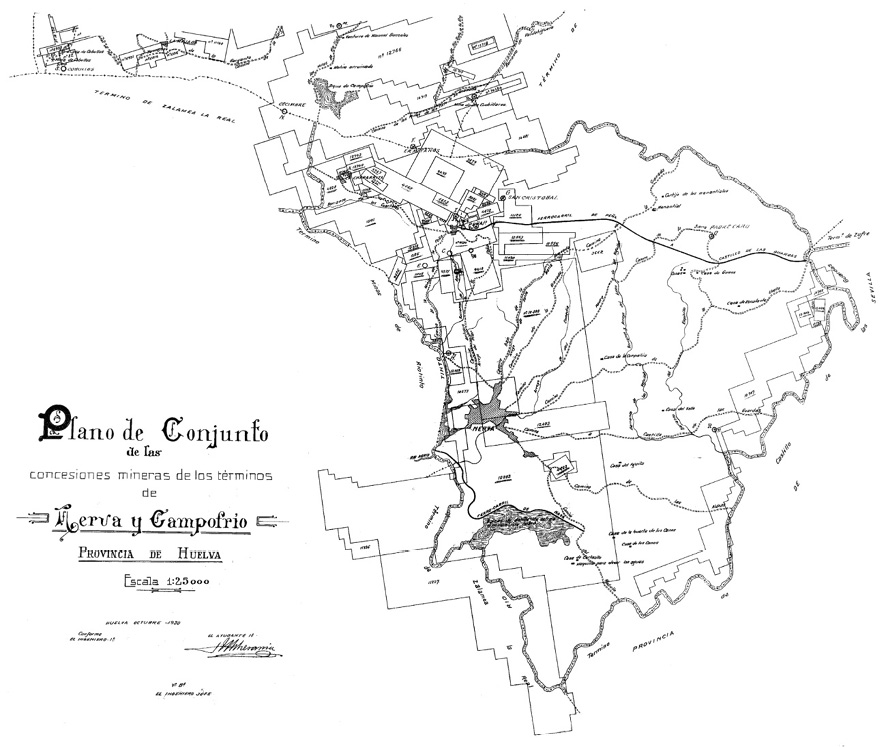

Map 2. Mining concessions of Nerva (the majority of the RTCL concessions were in the municipality of Minas de Riotinto)

Map 1. Map of the location of Nerva (Huelva)

In the municipal district of Nerva, there were two small population nuclei, Peña del Hierro and Los Ermitaños, inhabited almost exclusively by miners of the English company The Peña Copper Mines Company Limited, which had bought the mine in 1901 and built its own railway that connected the mine with the port of Seville (Pérez López, 2006). This nucleus had a population of 825 in 1910. In 1920, the company owned 201 houses (with 2 and 3 bedrooms), which they provided free of charge to the workers in order to stabilise the workforce and establish the population.6 Some workers of RTCL also lived in this nucleus.

The evolution of the population of the town in the decade1920-1929 was positive, except for the year 1921, due to the crisis after the general strike of 1920, which gave rise to a considerable reduction in the company’s workforce and the incentivised resignation of workers in the towns of the area due to a lack of work.7

Table 2. General demographic data for Nerva, 1920-1929

|

Year |

De facto population |

Year-on-year difference |

Mine workers |

Births |

Deceased |

Deceased < 5 years |

Vegetative growth |

|

1920 |

14,972 |

|

506 |

409 |

99 |

97 |

|

|

1921 |

14,501 |

- 471 |

2,565 |

487 |

362 |

82 |

125 |

|

1922 |

14,568 |

67 |

2,553 |

547 |

338 |

76 |

209 |

|

1923 |

14,676 |

108 |

2,363 |

457 |

293 |

52 |

164 |

|

1924 |

14,839 |

163 |

2,662 |

461 |

261 |

48 |

200 |

|

1925 |

15,293 |

454 |

2,839 |

401 |

304 |

58 |

97 |

|

1926 |

15,425 |

132 |

2,903 |

442 |

304 |

91 |

138 |

|

1927 |

15,838 |

413 |

3,100 |

432 |

263 |

45 |

169 |

|

1928 |

15,939 |

101 |

3,485 |

495 |

278 |

57 |

217 |

|

1929 |

16,121 |

182 |

3,590 |

488 |

256 |

56 |

232 |

Source: Elaborated using the data of AHMFRT, file 1815.

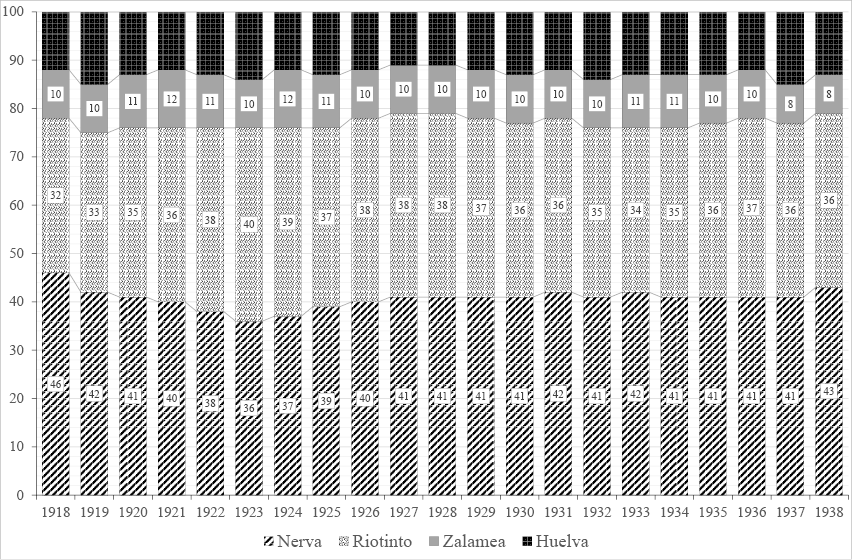

Figure 2. Residence of the workers of the labour force of the Mine Department of RTCL, 1918-1938 (%)

Source: AHMFRT. Personnel Registration Office and Report of the Deputation of the Board (annual report to the Governing Board Committee) 1918-1935, file 1805.

A noteworthy element characteristic of the majority of the mining areas was the peculiar sex ratio at the initial stage of their establishment and at times of the highest growth in the demand for labour. In general, the predominance of men in the mining area increased between 1877 and 1910, when there was a strong contribution of men from different origins with an insufficient female contribution, due partly to the type of labour and its instability.

The evolution of the sex ratio in the area displayed a trend towards equilibrium in 1897, which reflects the first stabilisation of the population of the mining area with an equal proportion of men and women. From 1910, there was equilibrium in the three municipalities which show the stabilisation of the population.

3. Social and wage strategies of RTCL

This section is important because the actions taken by RTCL in terms wages had an impact on the mining area, determining the prices of basic products. The intervention in the diet of the workers constituted an essential pillar of the industrial welfare policy of the company from 1913. The first reference to the existence of a store for the sale of food to the workers dates back to 1878. It was called Store 2 and sold basic food products, although its supply gradually broadened to include other products and goods. At first the workers bought with “vouchers” that they received from the company in the form of a truck system. From 1890, purchases were made in cash or with cash advances made by the company. Only the workers on the “Fixed wages list”8 could buy on credit. In 1892, the store was extended due to the increase in demand from the workers and it opened small branches, including one in Nerva. In 1907, the central store of Minas de Riotinto opened a new facility, selling other products as well as food (clothing, footwear, tobacco, wine, linen, cloths, furniture and household goods )9. In this year branches of Store 2 were opened in other parts of the mining area (Atalaya, Dehesa, Naya, Mesa de los Pinos, El Valle, Estación de Río Tinto) including Nerva, and in 1920 it had expanded to Campillo, Berrocal, Manantiales and Niebla, covering practically the whole of the mining territory in which the company operated 10. The price of the articles were fixed by a Board formed by representatives of RTCL and the workers.

The supplies of the stores in the period 1900-1930 were provided by companies around the country. Therefore, the sales staff were authorised to travel on the mining railway. They also used internal resources from the company’s own orchards and fields, which, after being divided, were leased to workers of the company for an annual rent11. A company farm began operating in 1905. It supplied the store with pork, eggs, cow and goat’s milk, etc. In 1913, the company constructed an abattoir in the suburbs of Minas de Riotinto for small cattle and pigs, divided into two sections, one managed by RTCL in order to supply its stores and another that it leased to the local council12. In line with the cheap food supply policy, the company established a bakery with mechanical dough mixers driven by an electrical motor and four ovens. Eight bakers worked there in three shifts of eight hours, making between 5,000 and 6.000 kilos of bread each day.13

Table 3. Workers listed in the Payrolls and Consumption Passbooks provided during 1919.

|

Department |

Number of workers at work in 1919 |

Number of operators who have a consumption booklet |

Operators who do not have a consumption booklet |

Percentage of workers with passbook |

|

Counter mine |

969 |

871 |

98 |

89.9 |

|

San Dionisio |

876 |

819 |

57 |

93.5 |

|

Muelle San Dionisio |

71 |

65 |

6 |

91.6 |

|

Corta San Dionisio |

1,270 |

906 |

364 |

71.3 |

|

Corta Filón Norte |

418 |

350 |

68 |

83.7 |

|

Corta Filón Sur |

861 |

708 |

153 |

82.2 |

|

Foundry |

1,148 |

951 |

197 |

82.8 |

|

Cementación Cerda |

320 |

259 |

61 |

80.9 |

|

Cementación Naya |

514 |

433 |

81 |

84.2 |

|

Exterior Naya |

140 |

100 |

40 |

71.4 |

|

New Workshops |

558 |

383 |

175 |

68.6 |

|

Mine traffic |

249 |

230 |

19 |

92.4 |

|

Traction |

288 |

192 |

96 |

66.7 |

|

Mine rails |

425 |

363 |

62 |

85.4 |

|

Rails and works |

127 |

110 |

17 |

86.6 |

|

Electricity plant |

118 |

94 |

24 |

79.7 |

|

Sulphuric acid |

93 |

63 |

30 |

67.7 |

|

Conservation of houses |

463 |

316 |

147 |

68.3 |

|

Houses and mountain |

289 |

237 |

52 |

82.0 |

|

Laboratory |

18 |

7 |

11 |

38.9 |

|

Store nº. 2 |

233 |

101 |

132 |

43.4 |

|

Administration |

144 |

70 |

74 |

48.6 |

|

Guards |

273 |

269 |

4 |

98.5 |

|

Stables |

8 |

8 |

100.0 |

|

|

Medical services |

45 |

33 |

12 |

73.3 |

|

Water service |

178 |

167 |

11 |

93.8 |

|

Public hygiene |

34 |

27 |

7 |

79.4 |

|

Classification |

45 |

27 |

18 |

60.0 |

|

TOTAL |

10,175 |

8,159 |

2,016 |

80.2 |

Source: AHMFRT, file 1835.

The company sought to maintain the wages at pre-war levels. This inadequate income led to an insufficient diet and, therefore, clear symptoms of physical deterioration among the workers which, as indicated by R. Williams in his report of 192014 translated into poor performance and a loss of productivity for the company. A physical examination conducted among the workforce in 1918 revealed that of a total of 9,856 workers, excluding children, only 32.6% had an adequate level of physical fitness for the work that they carried out. Between 1921 and 1925, the company brought back its industrial welfare policy of maintaining the prices of basic foods low and the Chairman of the company, Lord Milner, supported the acquisition of new land and the recovery of calcinated land to increase the supply of food15. The company sought to lower its prices as much as possible and conducted exhaustive studies on the prices of the commissaries of the large mining and industrial companies of the country. the markets of the main cities and even of the “free” stores in the towns in the mining area, particularly Nerva, which was the town where there were most food shops, given the number of workers who did not have a consumption passbook. These studies enabled it to evaluate prices as a measure to lower wage costs.

In 1917, an attempt was made to restructure the functioning of the commissary (Store 2) and its stores. The company sought to control access and therefore anyone who was not on the company’s payroll could not have a card16. This measure penalised those workers who had been deregistered after the strike of 1913. However, this did not prevent the workers from resorting to alternatives and the cards circulated among them. The company’s reaction was based on a proposal by Gordon Douglas, of the British Staff to Mr. Low, chief of the Employment Agency, to create new booklets17. The workers had to return their booklets, which would be changed in the Employment Agency for other new “safer” ones and the only holder of the booklet would be the breadwinner. The agency requested information from the different departments of the company (name and surname of the booklet holder, serial number on the pay roll, civil status, number of people in the booklet as direct family members, etc.). These data were validated by the clerks of each department. In short, each family had a one passbook and the purchases that they made were noted in it.

Table 4. Comparative prices of some articles between the RTCL Stores and the average prices in the grocery’s store of Nerva (pesetas/kilo) in the year 1918.

|

Products |

Comparative prices |

Products |

Comparative prices |

||

|

Stores RTCL |

Food shops |

Stores RTCL |

Food shops |

||

|

Olive oil |

2.10 |

2.15 |

Chickpeas 1st |

1.00 |

1.10 |

|

Sugar |

1.90 |

2.00 |

Chickpeas 2nd |

0.90 |

0.90 |

|

Pork spicy sausage |

4.60 |

6.00 |

Hams |

7.00 |

7.50 |

|

Blood sausage |

2.70 |

5.00 |

Iberian spicy sausage |

10.00 |

12.00 |

|

Bacon |

4.50 |

5.00 |

Ewe’s milk cheese |

5.00 |

5.50 |

|

Red wine |

0.40 |

0.50 |

Regular coffee |

4.00 |

4.00 |

|

1st grade soap |

1.50 |

1.80 |

Sultanas |

1.00 |

1.10 |

|

Soap 2nd |

1.20 |

1.40 |

Tomatoes 12/can |

0.45 |

0.50 |

|

Beans |

0.85 |

1.00 |

Peppers 12/can |

0.85 |

0.90 |

|

Potatoes |

0.25 |

0.35 |

Rice 2nd |

0.75 |

0.80 |

Source: AHMFRT, File 1815.

During the years of the First World War, the company adopted the measure of subsidising the prices of basic food items in order to mitigate the loss of purchasing power of the families and avoid labour conflicts. Therefore, it was necessary to adjust the functioning of the “consumption passbooks” that the workers received (Table 3). At the end of the war, the company increased its control over the booklets and eliminated the subsidies for basic products, which, combined with the insufficient increase in wages gave rise to unrest in the population of the whole of the mining area, which culminated in the general strike of 1920.

Another analysis of 1920 conducted by Gordon and G.W. Gray for the chairman of the company18 indicated that the wage increases during the period 1915-1920 had not covered the increase in the cost of living and that the majority of the workforce was worse off than in 1914. They considered that the minimum wage had been too low for the married men and that there was a high percentage of men employed with this salary, which negatively affected the productivity and efficiency of the company. With respect to the company’s commissary and its local branches, they indicated that the low price policy should be maintained at such a level so that with the same wage the workers could live adequately and the local shops where some of workers bought their food would not have to close. The most plausible alternative that they proposed to the company was an adjustment of food prices to obtain a small profit to cover expenses and not incur large losses. These “benevolent” measures of the company in terms of the diet of the workers and their families formed part of its more general industrial welfare policies, aimed at improving the quality of work and lowering wage costs (Table 5). A collateral effect of these policies was the segmentation of the workers. On the one hand, the so-called “sons of the village” residing in Minas de Riotinto and its hamlets, established for generations and with greater access to better work positions and19, on the other hand, the less stable working population, mainly residing in Nerva and which only had the option of accessing the hardest and most dangerous jobs. A good part of these workers bought their food in the local shops at higher prices that those of the company commissary. With the mining crisis, this latter group was excluded from the benefits of the paternalist programme and without the possibility of emigrating they became the organisers of the protest against the company in 1920.

Table 5. Sales of some of the foodstuffs and hygiene products in the RTCL company shops in 1918.

|

Products |

Number of kilos sold |

Average cost price (ptas./kg) |

Average selling price (ptas./kg) |

Benefits for the company (ptas./kg) |

Annual sales benefits for the company (ptas.) |

|

Olive oil |

26,273 |

1.783 |

1,930 |

0.147 |

3,862.1 |

|

Sugar |

72,827 |

1.475 |

1.580 |

0.105 |

7,646.8 |

|

Beans 1st class |

11,959 |

0.829 |

0.900 |

0.071 |

849.0 |

|

Beans 2nd class |

10,506 |

0.757 |

0.850 |

0.093 |

977.1 |

|

Rice 2nd class |

22,278 |

0.678 |

0.700 |

0.022 |

490.1 |

|

Codfish |

17,161 |

1.920 |

2.000 |

0.080 |

1,372.8 |

|

Quince candy |

13,615 |

1.077 |

1.210 |

0.133 |

1,810.8 |

|

Premium soap |

30,939 |

1.347 |

1.450 |

0.103 |

3,186.7 |

|

Second-hand soap |

24,558 |

1,020 |

1.150 |

0.130 |

3,192.5 |

|

Potatoes |

132,422 |

0.205 |

0.180 |

-0.025 |

-3,310.5 |

|

Ewe’s milk cheese |

5,386 |

3.600 |

3.800 |

0.200 |

1,077.2 |

|

Salted pork shoulder |

2,144 |

3.708 |

4.000 |

0.292 |

626.0 |

|

Ham |

9,199 |

4.030 |

4.555 |

0.525 |

4,829.5 |

Source: AHMFRT, file 1815.

After 1925, the new chairman Mr. Geddes reapplied the restrictive policy, ordering the paralysis of the purchases, repopulating the land with trees in order to sell it. On the other hand, the company believed that it had found the solution to the supply of foodstuffs by resorting to the private initiative as it thought that this would moderate prices through competition. The effect was the opposite and food prices shot up in the authorised private shops and establishments with the resulting pressure on wages. In 1929, the company brought back subsidies for basic foodstuffs, extending its facilities and increasing the sale of meat.

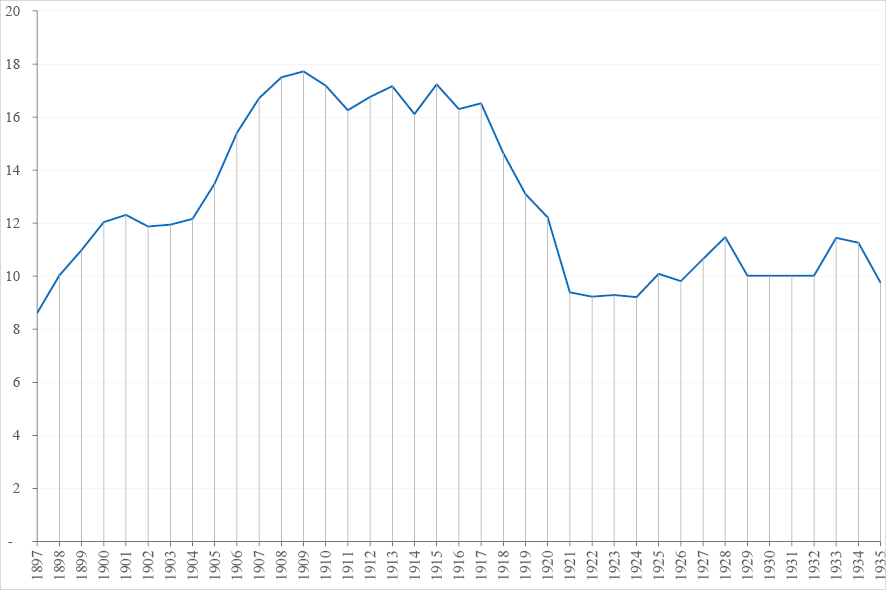

The interest of the company in its industrial welfare policies, particularly those referring to the diet of the workers and their families, was closely related to the control of the wage mass and the increase in productivity through the improvement in the nutritional status (Figure 3). This “paternalism” like others, was fairly discretionary and variable over time. It was not consolidable and was aimed at awarding the conduct of the workers of the company.

Figure 3. Number of food rations given to consumption passbook holders with an average of 4 rations per day, 1897-1935 (millions of rations)

Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from AHMFRT, File 1805.

4. The population of Nerva based on the municipal register of inhabitants 1924, general and employment characteristics and family composition

Below is a description of the principal elements of the population of Nerva in 1924 and its family structure.

4.1. General characteristics

The 1924 municipal register of Nerva recorded 13,969 people, with a fairly balanced distribution between men and women (6,981 and 6,988 respectively) and with a proportional distribution for the different age groups (Figure 4). This population was grouped into 3,362 households, whose distribution by size can be seen in Table 6. The largest number of households was the four-member household group and the group with the most population was that of the five-member households. 50.5 % of Nerva’s population resided in households with five or more members.

Figure 4. Population pyramid of Nerva in 1924.

Source: Own elaboration based on the data of the population register of Nerva 1924.

Table 6. Distribution of the number of households in the municipal register of Nerva of 1924 by the number of members (number of households and people included and percentages of the total)

|

Number of members |

Number of households |

% of households |

Number of people |

% of total population |

|

1 |

176 |

5.2 |

176 |

1.3 |

|

2 |

532 |

15.8 |

1,062 |

7.6 |

|

3 |

651 |

19.4 |

1,953 |

14.0 |

|

4 |

688 |

20.5 |

2,752 |

19.7 |

|

5 |

566 |

16.9 |

2,835 |

20.3 |

|

6 |

360 |

10.8 |

2,172 |

15.5 |

|

7 |

203 |

6.0 |

1,414 |

10.1 |

|

8 |

108 |

3.2 |

856 |

6.1 |

|

9 |

50 |

1.5 |

450 |

3.2 |

|

10 |

17 |

0.5 |

170 |

1.2 |

|

11 |

6 |

0.2 |

66 |

0.5 |

|

12 |

3 |

0.1 |

36 |

0.3 |

|

13 |

1 |

0.0 |

13 |

0.1 |

|

14 |

1 |

0.0 |

14 |

0.1 |

|

3,362 |

13,969 |

Source: Own elaboration based on the data of the population register of Nerva 1924.

The predominant type of family was the nuclear family. As we can see in Table 7, according to the Laslett classification, number 3 included the majority of the municipality’s population (78.1 % of the number of families20). Within them, 55.4% of all families were in type 3b and this is the group in which this study will focus the income analysis.

The number of people who lived alone was relatively small, 176. Its distribution by age varied depending on gender. Until the age of 60, there was a higher number of men and women predominated after this age21. We should take into account the difficulties suffered by the mining basin in the second decade of the twentieth century, with an enormous reduction in the workforce of RTCL from the more than seventeen-thousand workers in 1909 to less than eight thousand in 1924. This translated into an exodus of the population from these municipalities (helped by the company, as we have mentioned), with the subsequent reduction in its workforce. All of this must have distorted the organisation of the population in the towns under study.

Table 7. Distribution of the types of family according to the Laslett classification in the municipal register of Nerva of 1924*

|

a |

b |

c |

d |

Total |

|

|

1 |

176 |

||||

|

2 |

29 |

75 |

104 |

||

|

3 |

323 |

1,862 |

295 |

145 |

2,625 |

|

4 |

200 |

59 |

69 |

131 |

459 |

|

5 |

0 |

* In summary 1: solitary people; 2: non-family households (a: cohabiting siblings and b: other relatives); 3: simple families (a: married couple without children; b: with children; c: widowers with children; e; widows with children); 4: extended units with relatives (a: married couple with a parent; c: with siblings; d: combinations of the two).

The average age of marriage in 1924 in Nerva was 27.3 for men and 23.8 for women22. There had been few changes since 1901, when it was 27 for men and a slightly lower age in the case of women at 22 (there was a considerable gap between the two spouses). On a global level, it was a relatively young age if we compare it to the provincial averages of Huelva for 1920 and 1930: 28.4 and 28.7 for men, respectively and 26.3 and 26.6 for women (Cachinero, 1982: 92-93). The employment opportunities must have influenced this, together with the fact that the activity involved a high risk, so the family constituted a kind of insurance against any occurrence.

Compared with other mining nuclei, this average age of marriage was somewhat higher. We have calculated it for Linares in 1924: 25.9 for men and 23.2 for women. In the case of Mieres, in 1910, the age of marriage was 25.9 and 23.2, respectively23. The similarity in the average age of women in the three municipalities is striking.

With respect to the level of education, 63.6 % of men over the age of ten knew how to read and write as opposed to 46.8 of women24. This was a higher level than that of other mining basins. For example, for Linares in the same year, 56.3% and 37.0% of the men and women over the age of ten were illiterate. In any case, the level of education was below the Spanish average in these years (Carreras and Tafunell, 2005), despite the educational policy that RTCL had developed in the mining basin.

4.2. The professional structure of the population of Nerva

Determining the profession of the population through the municipal registers is a complex task and not exempt from imprecision, given that they are based on the declarations of the survey respondents and, therefore, depend on the personal concept that the individuals had of their occupation25. One example is the profession of miner, which is declared 45 times in the Municipal Register of Inhabitants of Nerva of 1924. However, in the same year, the Mines Department of RTCL employed 2,584 workers residing in Nerva (see Annex and Figure 3), of which 783 were strictly “miners”26. The diligence with which the interviewers recorded the data was also an influential factor. There was another department of RTCL, Traffic (rail), in which a total of 56 people residing in the town also worked but their professions are not reflected in the Register27. These elements call into question the information of the occupations declared by the inhabitants in the Register and have led us to use alternative sources, whenever possible, in order to refine the analysis of professions, occupations and income and avoid biases and deficiencies.

According to the Municipal Register of 1924, the population of Nerva was 13,967 inhabitants and using the professional HISPA_HISCO28 classifier, we have elaborated Table 8, which shows the difficulty in using the afore-mentioned source as the majority of the individuals declare an occupation that is difficult to define.

Table 8. Occupational classification of the population of Nerva in 1924 according to HISPA_HISCO categories.

|

Mayor Group Adaptado 1 |

Number |

Average declared salary (ptas./day) |

|

101 No profession recorded |

2,272 |

3.98 |

|

102 Students |

1,546 |

|

|

103 Household chores |

5,409 |

3.66 |

|

104 Pensioners and retired persons |

135 |

1.07 |

|

105 Owners and renters |

43 |

7.21 |

|

106 Beggars |

1 |

|

|

Total |

9,406 |

|

|

Mayor Group 00/01 Professionals and technicians |

||

|

121 Lawyers |

1 |

|

|

031 Draughtsmen |

2 |

4.50 |

|

071 Nurses |

9 |

6.83 |

|

067 Pharmacists |

2 |

|

|

065 Veterinarian |

1 |

|

|

037 Engineers |

2 |

|

|

133 Teachers |

26 |

5.50 |

|

061 Physician |

1 |

9.26 |

|

Total |

44 |

|

|

Major Group 02. Administrative and management workers |

||

|

219 Post Office Administrator |

1 |

15.00 |

|

226 Foremen and production managers |

2 |

6.75 |

|

300 Clerks and similar |

52 |

6.01 |

|

370 Postmen |

4 |

6.25 |

|

Total |

59 |

|

|

Major Group 04 Sales workers |

||

|

410 Trader-owners |

79 |

6.18 |

|

432 Travelling salesmen and the like |

2 |

5.75 |

|

451 Salespersons, trade employees |

62 |

3.61 |

|

Total |

143 |

|

|

Major Group 05 Service Workers |

||

|

540 Service staff: servants |

41 |

2.79 |

|

532 Waiters and similar |

3 |

2.00 |

|

570 Hairdressers and barbers |

34 |

3.92 |

|

551 Building guards |

8 |

6.39 |

|

Total |

86 |

|

|

Major Group 06 Agricultural workers… |

||

|

611 Agricultural operators |

11 |

4.75 |

|

627 Agricultural workers, gardeners… |

1 |

4.00 |

|

Total |

12 |

|

|

Major Group 07 Production workers… |

||

|

773 Slaughterers and butchers |

11 |

4.00 |

|

776 Bakers, confectioners and bakers’ workshops |

28 |

4.11 |

|

791 Tailors and dressmakers |

9 |

13.50 |

|

791 Dressmakers and seamstresses |

16 |

1.33 |

|

801 Shoemakers and cobblerss |

75 |

3.99 |

|

810 Carpenters |

38 |

6.33 |

|

830 Blacksmiths, mechanic fitters, machine operators… |

59 |

5.29 |

|

855 Electricians |

5 |

6.50 |

|

950 Bricklayers |

41 |

5.48 |

|

985 Drivers |

6 |

6.00 |

|

986 Carter |

14 |

4.00 |

|

Total |

270 |

|

|

Major Group Adaptado 10 Indefinite or ambiguous occupation |

||

|

Day labourers |

895 |

5.22 |

|

Miners |

45 |

5.33 |

|

Workers |

2,627 |

5.25 |

|

Military |

99 |

5.19 |

|

Industrialists |

141 |

8.18 |

|

Various trades |

139 |

4.77 |

|

Total |

3946 |

|

|

GRAND TOTAL |

13,967 |

Source: the data are from the Municipal Population Register of Nerva 1924. Municipal Archive of Nerva.

Of the total population, only 3,336 people declared their daily wage and, of these only 85 declared their annual salary. In order to determine wages, we used the comparative element of the wage slips that were paid in RTCL, in this case listing the occupations and professional levels (a total of 292)

Table 9. Summary of the wages expressed by the company RTCL (ptas./day)

|

Category |

Minimum |

Socio-economic |

Maximum |

|

Unskilled (1) |

5.22 |

5.84 |

6.46 |

|

Semi-skilled (2) |

6.30 |

7.30 |

8.30 |

|

skilled (3) |

7.61 |

9.18 |

10.75 |

|

Highly skilled (4) |

11.59 |

15.00 |

18.42 |

Source: AHMFRT, File 1805.

Note: The wages expressed in the municipal register of 1924 are average wages. The RTCL wages correspond to 6,706 workers of the Mines Department of whom 2,496 resided in Nerva and with a total of 228 occupations.

Table 10. Employment situation of the women in the municipal register of Nerva of 1924

|

Profession |

Number |

Number with wage |

Average wage |

Number with annual salary |

Average annual salary |

|

No data |

6 |

5 |

2.65 |

||

|

Carer |

1 |

||||

|

Embroiderer |

1 |

||||

|

Carpenters |

1 |

||||

|

Retailer |

5 |

1 |

30.00 |

||

|

Seamstress |

15 |

3 |

1.33 |

||

|

Maids |

21 |

2 |

0.66 |

||

|

Sales assistant |

4 |

||||

|

Employee |

2 |

2 |

3.00 |

||

|

Nurse |

3 |

1 |

2.50 |

1 |

500.00 |

|

Scribe |

1 |

1 |

4,380.00 |

||

|

Student |

691 |

||||

|

Industrial |

12 |

3 |

7.50 |

||

|

Day labourer |

17 |

7 |

4.36 |

||

|

Teacher |

12 |

1 |

5.00 |

5 |

2,200.00 |

|

Typist |

1 |

||||

|

Beggar |

1 |

||||

|

Miner |

1 |

1 |

5.75 |

||

|

Dressmaker |

3 |

||||

|

Nun |

7 |

||||

|

Labourer |

70 |

19 |

3.76 |

||

|

Pensioner |

2 |

1 |

0.75 |

1 |

275.00 |

|

Trade preparation |

1 |

||||

|

Landlady |

3 |

1 |

325.00 |

||

|

Servant |

20 |

2 |

10.00 |

||

|

Housewife |

4,962 |

57 |

3.19 |

3 |

1,196.67 |

|

Weaver |

1 |

||||

|

Shoemaker |

2 |

||||

|

Overall total |

6,987 |

109 |

3.79 |

12 |

1,672.50 |

Source: own elaboration based on the Historical Municipal Archive of Nerva, Municipal Register of Inhabitants of 1924.

If we examine the employment situation of women in the municipal register of 1924 (Table 10), from 6,978 declarations, we obtain a total of 4,692 (67.2% of the total) who declare that their work is “at home” although 80 of them declared that they obtained income from employment. In Nerva, the employment options of women were very limited, the production activities related to agricultural work were practically non-existent due largely to the pollution of the soil. There were only the allotments of RTCL which leased them to its workers at low prices. The most frequently declared professions were: labourers and day labourers (87), servants and maids (41), seamstresses (15), teachers (12) and industrial personnel (12). All of them declared their wages.

Table 11. Wages of the cleaners working for RTCL 1922-1924

|

Section or Department |

1922 |

1923 |

1924 |

1925 |

1926 |

|

ptas./day |

ptas./day |

ptas./day |

ptas./day |

ptas./day |

|

|

Counter mine |

2.90 |

2.90 |

2.90 |

2.90 |

3.10 |

|

Corta San Dionisio |

3.00 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

3.40 |

|

Corta Filón Sur |

2.75 |

2.75 |

2.75 |

2.75 |

3.20 |

|

Filón Planes |

2.75 |

2.75 |

2.75 |

2.75 |

3.00 |

|

Tunnel nº 5 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

|

Precipitación Naya |

2.40 |

2.40 |

2.40 |

2.40 |

2.45 |

|

Terreros Cerda |

2.40 |

2.40 |

2.40 |

2.40 |

2.45 |

|

Sulphuric acid |

3.30 |

3.30 |

3.30 |

3.30 |

3.50 |

|

Muelle S. Dionisio |

2.40 |

2.40 |

2.40 |

2.40 |

2.20 |

|

Mine traffic |

3.00 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

2.95 |

|

Electricity plant |

2.60 |

2.60 |

2.60 |

2.60 |

2.65 |

|

Water supply |

2.65 |

2.65 |

2.65 |

2.65 |

2.55 |

|

Geology |

3.10 |

3.10 |

3.10 |

3.10 |

3.20 |

|

Laboratory |

3.10 |

3.10 |

3.10 |

3.10 |

3.20 |

|

Doctor |

3.10 |

3.10 |

3.10 |

3.10 |

3.20 |

|

Naya sievers |

3.10 |

3.10 |

3.10 |

3.10 |

3.20 |

|

Conservation of houses |

2.95 |

2.95 |

2.95 |

2.95 |

3.00 |

|

Public hygiene |

2.95 |

2.95 |

2.95 |

2.95 |

3.00 |

|

Store nº. 2 |

2.95 |

2.95 |

2.95 |

2.95 |

3.00 |

|

Mine Workshops |

2.95 |

2.95 |

2.95 |

2.95 |

3.00 |

|

Management |

1.95 |

1.95 |

1.95 |

1.95 |

1.95 |

|

Schools |

1.95 |

1.95 |

1.95 |

1.95 |

1.95 |

|

Employment agency |

1.95 |

1.95 |

1.95 |

1.95 |

1.95 |

|

Average wage |

2.73 |

2.73 |

2.73 |

2.73 |

2.81 |

|

Average wage of maids in Nerva Register |

0.66 |

||||

|

Average wage of servants in Nerva Register |

10.00 |

Source: AHMFRT, File 1805.

In this case, RTCL also employed women in different occupations and we have wages to compare them with those declared by the women in the register of 1924. There are four wages declared in the Register for 41 cases of maids and servants (2 + 2) which is a very small number to establish an average daily wage. The use of the wages of the RTCL cleaners enables us to evaluate and estimate more precisely the average wage of these categories as the tasks were very similar (cleaning of the offices and their furniture, washing of household items and clothes, etc.). Again, the Register of Nerva includes a very low number of wages in this occupation.

Other categories for which we have business data are teachers, nurses, cleaning personnel and unspecified carers of the RTCL Mining Hospital and in this case there are also declarations in the Register of 1924. The wages reflected in the company’s payroll are higher than those declared by the teachers, nurses and seamstresses in the Register (Table 7).

Table 12. Wages of the employees of the RTCL Hospital and schools 1922-1925 and those declared in the Municipal Register of 1924.

|

1922 |

1923 |

1924 |

1925 |

|||||

|

Hospital professions |

Hours worked |

Wage (pts./day) |

Hours worked |

Wage (pts./day) |

Hours worked |

Wage (pts./day) |

Hours worked |

Wage (pts./day) |

|

Nurses |

10 |

2.25 |

10 |

2.50 |

9 |

2.81 |

9 |

3.00 |

|

Maids |

10 |

1.88 |

10 |

2.25 |

9 |

2.50 |

9 |

2.75 |

|

Cooks |

10 |

1.88 |

10 |

2.25 |

9 |

2.50 |

9 |

2.75 |

|

Seamstresses |

10 |

2.25 |

10 |

2.50 |

9 |

2.81 |

9 |

3.00 |

|

Nurse in Register |

2.50 |

|||||||

|

Seamstress in Register |

1.33 |

|||||||

|

Days worked |

Days worked |

Days worked |

Days worked |

|||||

|

Teachers |

6 |

4.25 |

6 |

4.25 |

6 |

4.75 |

6 |

5.00 |

|

Teaching assistants |

6 |

3.64 |

6 |

3.64 |

6 |

3.80 |

6 |

4.00 |

|

Teacher in Register |

3.00 |

|||||||

Source: AHMFRT, File 1813; Municipal Register of Inhabitants of 1924.

Employment opportunities for women in Nerva were fairly limited, which was a common scenario in many mining areas. The practical non-existence of agricultural activities, the absence of rural industries of consumer goods, the limitation of local services and the consolidation of the labour market in the area reduced the possibilities of paid work for women. As previously indicated, the presence of women as workers in the mines was relatively high in the final decade of the nineteenth century in “barcaleo” tasks (transporting the ore) at the crests and cementations with a 958 women in 1890, making up 10.6% of RTCL’s workforce, reaching a maximum in 1894 with 11.1% of the workforce (1,146 women). It was cheap labour as their wage was half of that of the men in the same job, and it was abundant and readily available29. The first reduction in RTCL’s workforce in 1895 led to the disappearance of women in the ore transporting tasks and their only presence was reduced to “subordinate tasks”, such as cleaners, cooks, hospital hands, commissary assistants, typists, secretaries, nurses and teachers. In 1923, the number of women employed by the company fell to its minimum level, representing just 0.94% of the workforce.

Another option for women to obtain income was that of “host”, which consisted in taking a recently arrived miner into their homes as a tenant to whom they also provided laundry and cooking services. This was relevant at times when the workforce was growing, with the mass arrival of single emigrant miners and the limited accommodation infrastructure in Nerva (houses, guest houses, bunk houses, etc.). With the maturing of the labour market and the decrease in the number of employees in RTCL’s workforce from 1916 and, particularly from 1921, the influx of immigrants to the town practically disappeared, giving rise to a predominantly local labour market. Within this context, this hosting activity became a very limited option for women. In the Municipal Register of Inhabitants of Nerva of 1924, we can find 65 guests distributed in the following way:

Table 13. Distribution of guests in Nerva in 1924

|

Houses |

Guests |

Number of guests |

|

1 |

1 |

41 |

|

8 |

2 |

16 |

|

1 |

3 |

3 |

|

1 |

5 |

5 |

|

11 |

65 |

Source: Municipal Register of Inhabitants of Nerva of 1924

As we can see, this option for earning an income for women almost disappeared. Finally, we should highlight the existence of 57 women who declared their “house” as their activity while also declaring wages. These situations probably refer to the provision of “host” services and part-time cleaning, laundry, etc. In short, the opportunities for women in Nerva and, in general, in the mining area of Río Tinto to obtain a wage were very limited, which undoubtedly affected the dietary situation of the families, as we shall see later.

4.3. Analysis of families with four and five members

We have selected families with four or five members with a father, mother and two or three children. In total, there were 489 and 420 families in each group (909 in total, representing 72.4 % of families of 4 and 5 members and 27.0 % of total households in Nerva)30. We have considered the five-member families as this was the usual trend of nuclear families. It is the model of family used by RTCL when calculating consumption and income and to an analyse the deficit.

In order to calculate the family income, we have taken what is declared in the register as a base. There are families that did not declare any occupation or income. For those who declared an occupation but did not indicate any income, we have assigned the average wage of their occupation, except in the case where we do not have any daily wages as a reference31. We have multiplied this wage by 1.3 in order to counter the underestimation of their income and to correct the differences in the value that labourers really earned for overtime or for producing more than the stipulated amount.

We have made all of these calculations by using different information on income of the workers who appear in the company lists for 1924 or the closest year. The task of reconstructing the payrolls of the inhabitants of Nerva is complex. It is true that a high percentage were employed by RTCL, which should have influenced what was earned in other mines (we are principally referring to Peña del Hierro) or other activities. In the RTCL lists that we have worked with, we have found the full name, which in many cases is not sufficient to find with certainty a person in the municipal register. Sometimes, the place of residence and address appear, which is relevant, and other times the age, which can be significant for our case. We find it strange that we were unable to find people in the municipal register for whom we had a lot of information and knew that they lived in Nerva. This could be due to the fact that they were not included in the register. We can confirm that the record of people who had moved away could be deficient. For example, there are hardly any people registered in the nucleus of Peña del Hierro, although we know that a considerable population of mine workers resided there.

Table 14. Expenditure of a family of four and five members in Nerva according to the consumption estimated by RTCL and the company’s commissary prices (Store 2) and those of the shops in Nerva. Values in pesetas

|

Family of 5 members |

Family of 4 members |

|||

|

Cost Store 2 |

Nerva shops |

Cost Store 2 |

Nerva shops |

|

|

Food |

5.12 |

5.51 |

4.22 |

4.52 |

|

House, lighting, coal |

0.60 |

0.60 |

0.55 |

0.55 |

|

Clothes and footwear |

0.50 |

0.50 |

0.45 |

0.45 |

|

Other expenses |

0.50 |

0.50 |

0.40 |

0.40 |

|

Total |

6.72 |

7.11 |

5.62 |

5.92 |

Source: AHMRT, File 1815. Detailed budget in Annex 4.

In the case of the young population, at that time, they began to work for RTCL at the age of 14 (in accordance with the labour law of mining). The company paid a specific wage for each age bracket of minors, considering them as such until the age of 21 (they were called “zagalones”). From then, they began to earn an adult wage, which was stipulated in accordance with the type of work that they carried out. Specifically, the general wages formalised in 192432 for minors in accordance with age are shown in Table 15.

Table 15. Daily wages of “children” established by RTCL for each of the age brackets in 1924, in pesetas

|

Age |

Daily wage |

|

14 |

1.95 |

|

14 ½ |

2.2 |

|

15 |

2.65 |

|

16 |

2.75 |

|

17 |

3.2 |

|

18 |

3.25 |

|

19 to 21 |

3.75 |

Source: AHMFRT, file 1805.

For this study, we have consulted the lists of minors employed by the company that indicated their age and income33. We know for certain that RTCL kept a record of the minors (both children of the company’s workers and the total inhabitants of the towns in the basin) and that it planned the recruitment of those who were approaching the minimum age to work. We have checked the names of these young people on the RTCL lists and the Register of Nerva, finding a few of them. In some cases they appear as labourers and in others they are not recorded as carrying out any activity or earning any income. This seems to corroborate that there was a certain kind of sub-registration of the minors employed.

Table 16 shows the percentages of minors between the ages of 10 and 16 who declared an occupation34. In order to correct some of these biases, we have considered all males from the age of 14 as being employed (although we believe that the general age of earning some kind of payment must have been lower). If no occupation or wage is included, we have assigned that corresponding to their age, corrected with the information on real income of the “zagalones” in RTCL.

Table 16. Percentage of men and women who declared that they had a job between the age of 10 and 16 in Nerva in the 1924 Municipal Register of Inhabitants.

|

Men |

Women |

|||||||||||||||

|

Age |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

Total |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

Total |

|

Nº |

10 |

7 |

19 |

22 |

52 |

72 |

106 |

291 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

4 |

7 |

11 |

32 |

|

% |

6.6 |

4.5 |

11.7 |

13.5 |

31.0 |

60.0 |

75.2 |

21.7 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

0.6 |

1.2 |

2.7 |

4.8 |

6.6 |

2.4 |

Source: Own elaboration with figures form the municipal register of inhabitants of Nerva of 1924.

We have calculated the annual amount of labouring tasks using the number of days worked appearing in the list of the company for different departments. The source used lists the tasks carried out by the men and women employed over the different months, which allows us to counteract any seasonal variations. We have obtained an average of 315 days of activity per year.

When calculating the number of days worked, we must take into account the specific leaves (illness, accident, etc.) or interruptions that could have occurred due to different circumstances in the company’s activity. Obviously, these elements are also visible in the accounting method used. However, in order to include other types of exceptional vicissitudes that may have occurred, we have taken the decision, always with a high level of randomness typical of these types of estimate, to round the number of days worked to 300 for the case of the municipality of Nerva.

This figure has been used in other cases, although there are also other estimates that considerably reduce the number of productive days. Our objective is not to undertake a general estimation but to adapt to the information with which we have for this basin. We should indicate that, given the difficulties to complement the family needs in this period, strategies had to be devised to make the most of the opportunities available for increasing income. In our case, we have multiplied the daily wage (adjusted with the afore-mentioned correction) by 300 and divided it by 366 (1924 was a leap year) in order to calculate the daily amount earned.

In the case of the women, the usual sub-recording in the historical municipal registers and censuses can be observed. It is true that the opportunities were very limited, given the fundamentally masculine nature of the principal economic activity, mining.

According to our calculations, taking as a base the wages that were declared in the municipal register of 1924 and all the afore-mentioned corrections, the average daily income for a family with four members (spouses and two children) was 7.39 pesetas and that of a five-member family (with three children) 8.77 pesetas. The contribution made by the breadwinner to the household income would be 6.06 pesetas and 6.06 pesetas per day on average for each of the families considered, representing 79.9% and 67.6 % of total income, respectively. We have calculated the average income of the head of the family for those with four and five members and where only the parents work. There are hardly any differences with the previous ones (they are only slightly higher). Specifically, they were 6.04 and 6.32 pesetas respectively35.

With respect to the analysis of professions, of the 909 families, 723 breadwinners indicated labourer as their occupation (529) and day labourer (194), representing 79.5 %36. We consider that a professional analysis using the HISPA-HISCO classification would contribute very little.

5. The dietary intake of the population of Nerva

As already mentioned, one of the strategies of the company was to control the food prices of Store Nº 2. In this respect, in the section on food, the company provided a list of basic foods with which to calculate the total expenditure per week in order to estimate family consumption (Table 17). In the data provided by the company, the calculation of the family budget was made for five members (father, mother and three children) but, as already mentioned in this article, there was a high number of four-member families (father, mother and two children), so we have made the calculations for both cases in order to determine the dietary intake of these families with the greatest precision possible.

Table 17. Weekly family budget for food alone in 1923. RTCL. Family composed of a father, mother and three small children.

|

Article. |

Monday |

Tuesday |

Wednesday |

Thursday |

Friday |

Saturday |

Sunday |

Weekly average |

|

Bread |

2000 g |

2000 g |

2000 g |

2000 g |

2000 g |

2000 g |

2000 g |

2000 g |

|

Sugar |

100 g |

100 g |

100 g |

100 g |

100 g |

100 g |

150 g |

107.14 g |

|

Coffee |

20 g |

20 g |

20 g |

20 g |

20 g |

20 g |

35 g |

22.14 g |

|

Pork fat |

180 g |

180 g |

180 g |

180 g |

180 g |

180 g |

154.28 g |

|

|

Sardines |

500 g |

500 g |

500 g |

500 g |

285.71 g |

|||

|

Cod |

100 g |

250 g |

250 g |

85.71 g |

||||

|

Meat |

125 g |

125 g |

250 g |

71.42 g |

||||

|

Black pudding |

60 g |

40 g |

100 g |

60 g |

60 g |

45.71 g |

||

|

Chickpeas |

150 g |

150 g |

125 g |

150 g |

150 g |

150 g |

125 g |

|

|

Milk |

250 ml |

250 ml |

250 ml |

107.14 ml |

||||

|

Potatoes |

625 g |

500 g |

625 g |

500 g |

500 g |

625 g |

625 g |

571.43 g |

|

Rice |

140 g |

210 g |

210 g |

80 g |

||||

|

Oil |

125 g |

125 g |

125 g |

80 g |

125 g |

80 g |

125 g |

112.14 |

|

Wine |

500 ml |

500 ml |

500 ml |

500 ml |

500 ml |

500 ml |

500 ml |

500 ml |

Source: AHMRT, File 1815

From these data provided by the company and the average weekly consumption, we have calculated the individual consumption of all the members of the family. In this case, due to a lack of other estimation methods as there is not enough individual anthropometric data, it has been assumed that all of the members of the family ate the same foodstuffs. This has been done on a macro level for dietary intake in Spain and, in turn, enables comparisons to be made with other studies37.

Table 18. Dietary intake of families with four and five members.

|

Food |

g/day |

5 members all eating the same (g) |

4 members all eating the same (g) |

|

Bread (g) |

2000 |

500.00 |

400.00 |

|

Sugar (g) |

107.14 |

26.79 |

21.43 |

|

Coffee (g) |

22.14 |

5.54 |

4.43 |

|

Pork fat (g) |

154.28 |

38.57 |

30.86 |

|

Sardines (g) |

285.71 |

71.43 |

57.14 |

|

Cod (g) |

85.71 |

21.43 |

17.14 |

|

Meat (g) |

71.42 |

17.86 |

14.28 |

|

Black pudding (g) |

45.71 |

11.43 |

9.14 |

|

Chickpeas (g) |

125 |

31.25 |

25.00 |

|

Milk (ml) |

107.14 |

26.79 |

21.43 |

|

Potatoes (g) |

571.43 |

142.86 |

114.29 |

|

Rice (g) |

80 |

20.00 |

16.00 |

|

Oil (ml) |

112.14 |

28.04 |

22.43 |

|

Wine (ml) |

500 |

125.00 |

100.00 |

In order to reconstruct this typical consumption estimated by the company, we have transformed the food amounts into nutrients (calories, proteins, fats and carbohydrates) and we have calculated micronutrients using the dietary measurement program EasyDiet© 38, which is a management program for diet-nutrition consultants designed together with Bicentury and AEDN (Spanish Association of Dieticians-Nutritionists) (Table 19). In order to calculate the amounts of nutrients, the coefficient of the edible portion of each food is applied, provided by the database 39. To carry out the estimate, raw foods have been considered as the data referring to their sale refers to kilogrammes of food in this state. However, we do not know how the food was prepared and cooked, which could substantially modify the nutritive properties and, therefore, this has not been taken into account.

Table 19. Nutrients per person for a family of 4 and 5 members

|

Elements |

Total nutrients (5 members all eating the same) |

Total nutrients (4 members all eating the same) |

|

Calories |

2,188.9 |

1,750.6 |

|

Proteins (s) |

81.6 |

65.3 |

|

Carbohydrates (grs.) |

305.9 |

244.9 |

|

Fats (grs.) |

62.4 |

49.6 |

|

Animal proteins (grs.) |

31.8 |

25.6 |

|

Calcium (mg) |

449.3 |

358.6 |

|

Iron (mg) |

15.2 |

12.1 |

|

Zinc (mg) |

6.1 |

4.9 |

|

Vit. A (µg) |

43.6 |

34.8 |

|

Folic acid (µg) |

180.9 |

144.8 |

|

Vitamin D (µg) |

7.8 |

6.3 |

Table 19 shows that the dietary intake could be very different for four and five-member families, so we have compared the consumption of the diet depending on the type of family with the needs for the Spanish population during the period studied (Table 20)40.

Table 20. Individual nutrient needs of the Spanish population, consumption and requirements

|

Elements |

Total nutrients (4 members all eating the same) |

Total nutrients (5 members all eating the same) |

Average daily needs of the Spanish population 1910 |

Average daily needs of the Spanish population 1930 |

|

Calories |

2188.9 |

1750.6 |

2,266 |

2,286 |

|

proteins (grs) |

81.6 |

65.3 |

||

|

Carbohydrates (grs) |

305.9 |

244.9 |

||

|

Fats (grs) |

62.4 |

49.6 |

||

|

Animal proteins (grs) |

31.8 |

25.6 |

42.8 |

43.1 |

|

Calcium (mg) |

449.3 |

358.6 |

1,051 |

1,052 |

|

Iron (mg) |

15.2 |

12.1 |

12.5 |

12.6 |

|

Zinc (mg) |

6.1 |

4.9 |

13.8 |

13.9 |

|

Vit. A (µg) |

43.6 |

34.8 |

778 |

785 |

|

Folic acid (µg) |

180.9 |

144.8 |

349 |

352 |

|

Vitamin D (µg) |

7.8 |

6.3 |

15.5 |

15.5 |

In the light of these results, we can see how the company failed in its attempt to cover the needs of the population in order to be able to adjust as much as possible to the wages, as only the calorie needs could be covered in some cases, but not the rest of the micronutrients. In the data displayed in Table 20 we can observe how the nutrients consumed by the male population of Río Tinto were lower in terms of animal proteins, calcium, zinc, vitamin A, folic acid and vitamin D, when compared with the data of the needs of the Spanish population for the same period. Only in the case of a four-member family was the average consumption of calories close to the daily needs, but that of the rest of the macro and micronutrients was deficient. This would partly explain the physical deterioration of the workers mentioned in this study and the constant desire of the company to analyse these deficiencies as shown by its interest in the consumption of the workers and the reports that highlight the problems in the population and the attempts to compensate the diet by providing allotments to its workers to complement their diet.

Moreover, when interpreting the dietary data, we have considered it relevant to emphasise the minimum protein needs that the body needs to ensure growth and sustenance, the value of which fluctuated between 0.8 and 1 grs of protein/kg of adult body weight41. In this case, between 48 and 60 grs of protein would be needed to cover the basic needs. However, this metabolic usage is only possible if the body’s basic energy needs are covered at the same time, as, otherwise, the proteins would be used as cellular fuel. Therefore, if we compare the data referring to nutrient needs in Table 20 with dietary intake, we can observe how the protein requirements were covered but they were not used correctly until the calorie needs had been covered. With respect to the consumption of micronutrients, the data show the existence of deficiency diseases, also known as hidden hunger42. The considerable calcium deficit gave rise to osteoarticular diseases, such as fractures. Furthermore, a vitamin A deficit could lead to difficulties to adapt to the dark and even blindness, together with growth disorders in children. The large vitamin D deficit, in addition to the low level of sunlight that they received, led to situations of rickets among children and fractures or bone weakness in adults, among other diseases43.

Taking all of the above into account, it is difficult to establish a family expenditure that covers the nutritional needs, given that we lack the necessary information and consumption was determined by socio-demographic elements of the period. In any case, in order to assess the capacity of the household income, we will use as a base the minimum consumption that the company calculated for a family of five members. For a family of four members, we have subtracted 20% of expenditure of food following the indications in the previous paragraphs of assuming that all members ate the same. We have updated the prices of the diet of 1923 with the prices of the RTCL commissary 44and the shops in Nerva. The results show that for a five-member family, the average cost was 6.73 pesetas/day with the commissary prices and 7.11 with the prices of the shops in Nerva (table breaking down the expenses in Annex 4). The average income of the breadwinner in Nerva (6.06 pesetas) was a little lower than these amounts. In the case of a four-member family, the income of the breadwinner (5.91 pesetas) was almost the same as the cost of the above-described diet (5.62 and 5.92 pesetas depending on the place of purchase). Taking into account the total income (8.77 pesetas for a family of five members and 7.39 pesetas for a four-member family), the minimum level of consumption indicated by the company was covered. If we only take into account the households whose breadwinner declared the occupation of labourer or day labourer, the majority of the families 45 barely exhibited differences with the previous calculations46.

In summary, according to the data in the municipal register of Nerva and our calculations, it may be observed that for the households of four and five members, the family incomes sufficiently covered the minimum consumption indicated by RTCL. The wage of the breadwinner was close to this minimum. It was a population nucleus connected to the mining activity, completely masculinised in this basin and with few possibilities for alternative employment for women. Families complemented their income principally through the employment of children, who had many possibilities to be recruited by RTCL from the age of 14. We should bear in mind that in the year analysed there was a good economic climate in the basin and the number of employees in the mines increased47. Employment opportunities also increased the possibilities of increasing the wage with overtime and with a more continuous activity throughout the year48.

5. Other analysis possibilities

We have seen the difficulties in characterising the population with the information provided by the municipal registers, particularly due to the lack of specification of the jobs and the inclusion of the majority of them in fuzzy categories, such as labourer or day labourer. Furthermore, there are other elements that are not taken into account and are related to the standards of living, such as the type of household, the services in the place in which they lived, localisation problems, etc.

To respond to this, we propose the use of geographic information systems, which enable us to analyse these aspects and determine other characteristics of the population. These types of programme have improved considerably. They are freely available and have an enormous processing capacity. In addition, it enables us to access geographical information that is continuously expanding and that provides information on the national and regional institutions.

6. Conclusions

The large-scale development of mining by RTCL from the end of the nineteenth century led to a huge increase in the population of the area. So much so that several hamlets were detached from the largest municipality Zalamea la Real and became independent municipalities. This was the case of the new municipality of Nerva, created in 1885, which became the principal population nucleus of the area. One of the characteristics of this town is that the properties of RTCL were inferior to those of other municipalities in the area and the number of privately-owned dwellings was higher than those owned by the company. Services were also private: shops, guest houses, bars and taverns, casinos, etc. This feature made the town an alternative refuge for the miners, given that here the company had limited power. This fact facilitated the growth of its population and its transformation from a mining camp to a solid municipality, with a large number of its residents working for the mining company and in other occupations related to alternative services.