AREAS Revista Internacional de Ciencias Sociales, 47/2024 “Family Budgets and Living Standards in Spain in the 1920s”, pp. 67-94. DOI: https://doi.org/10.6018/areas.630511.

Budgets of Working Families in the Area of Bilbao Estuary (North of Spain) in 1924

Jose M. Beascoechea-Gangoiti, University of the Basque Country

Arantza Pareja-Alonso, University of Granada

Susana Serrano-Abad, University of the Basque Country

Abstract

The article reconstructs wages and expenses to estimate the budgets of urban working-class families with dependent minor children during the 1920s. The scope of the study is the metropolitan area of the Bilbao Estuary, considering its complex social and economic composition. Residential (Getxo) and industrial (Sestao) towns on both sides of the estuary were selected, as well as central and peripheral working-class district areas of the city of Bilbao. The primary source used is the registers of inhabitants corresponding to these municipalities for the year 1924.

Key words: Bilbao Estuary, budgets, salaries, expenses, working-class families

Presupuestos de las familias trabajadoras del área de la Ría de Bilbao (Norte de España) en 1924

Resumen

El artículo reconstruye los salarios y los gastos para estimar los presupuestos de las familias obreras urbanas con hijos menores dependientes durante la década de 1920. El estudio se centra en el área metropolitana de la Ría de Bilbao, considerando su compleja composición social y económica. Se seleccionaron núcleos residenciales (Getxo) e industriales (Sestao) en ambas márgenes de la ría, así como zonas centrales y periféricas de los barrios de clase obrera en la ciudad de Bilbao. La fuente principal son los padrones de habitantes de estos municipios correspondientes al año 1924.

Palabras clave: Ría de Bilbao, presupuestos, salarios, gastos, familias obreras

Date of receipt of the original: September 13, 2024: final version: December 10, 2024.

- Jose M. Beascoechea-Gangoiti, Universidad del País Vasco/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea. E-mail: jm.beascoechea@ehu.eus;

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1473-3948

- Arantza Pareja-Alonso, Universidad de Granada. E-mail: arantza.pareja@ugr.es; ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3141-624X

- Susana Serrano-Abad, Universidad del País Vasco/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea. E-mail: susana.serrano@ehu.eus; ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7626-0157

Budgets of Working Families in the Area of Bilbao Estuary (North of Spain) in 19241

Jose M. Beascoechea-Gangoiti, University of the Basque Country

Arantza Pareja-Alonso, University of Granada

Susana Serrano-Abad, University of the Basque Country

1. Introduction

The relationship between wages and the cost of living of the working class has been a constant concern in Basque contemporary historiography since a group of researchers began to study the bases of the industrialisation process, the formation of the working class and the new capitalist society in the Basque Country. Ignacio Olábarri (1978), pioneer in this research, in his study on work and workers’ organisations in Biscay during the Restoration, compiled relevant information on the working-class labour force, working hours and the nominal and real wage indexes2.

Meanwhile, Manuel González Portilla (1981) dedicated the last two chapters of the second volume of his study on the industrial boom and the new Basque capitalist society during the period 1876 to 1913 to two directly related issues: first, a demographic analysis (growth, age structure, mortality and migratory movements); and second, the situation of the working class in Biscay, including the evolution of the day labourers. For the latter, his principal source was the series of the labourers of the port of Bilbao, a very specific group, which he related to the prices of basic necessities and rents. In short, he concluded that this group of workers became weaker. They suffered from diseases and a high mortality rate but their standard of living did not improve, converting the defence of purchasing power into the principal cause of the social movements of that time.

One decade later, in response to the growing historiographic concern about the living standards of the working class, Fernández de Pinedo (1992) and, subsequently, Pérez Castroviejo (1992) addressed this issue using the documentation until the first third of the twentieth century of the company Altos Hornos de Vizcaya, located on the left bank of the Estuary. They both studied the evolution of nominal wages, the prices of consumer articles, the composition of the shopping basket and the cost budgets, calculating a real wage, the behaviour of which varied before and after the First World War. However, Pérez Castroviejo (2006) considered that the supplements to the daily wage, such as overtime payments, were difficult to determine in the nominal wage, which hindered the calculation of the real wage levels.

Also joining the debate in these years was the historiographer Pilar Pérez-Fuentes who, in 1993 published a pioneering study analysing aspects that until then had been absent from Basque historiography. This author presents the survival strategies of the mining community, a “very peculiar microcosmos” and argues that it was impossible for the day labourers who were the breadwinners of the family to guarantee survival, so the economic contribution of the women was necessary through providing lodging services and performing domestic work in other homes. The final chapter elaborates the family budgets of the miners of Trapagaran, according to the relationship between the cost of family consumption and the income contributed by all of the members, including women. Along the same lines, Rocío García Abad (1999; 2004) continued to research the mining basin of Biscay and the Bilbao Estuary, using a broader sample made up of this decisive contribution of the women to sustain the family. Subsequently, the living conditions of the mining population of Biscay were also studied from a more classical approach (Escudero and Barciela, 2012).

Recently, Stephan Houpt and Juan Carlos Rojo (2023), together with Houpt (2023), have resumed the study of the workers of the Bilbao Estuary, analysing their standards of living and family vulnerability between 1914 and 1935, using new sources and variables. They insist on the need to consider the income of all members of the family, not only of the male members, and to observe the family life cycle to measure the changes with precision. To do this, they have also used the nominal wage salaries of the middle-skilled workers of Altos Hornos de Vizcaya and have elaborated a new monthly family consumption basket. Their results highlight the vulnerability of working-class families of the Estuary to the frequent reduction in incomes during the inter-war period, often living on the line of subsistence.

This research is based on these theses but proposes a new approach to addressing both some of the issues that have attracted the attention of the historiography and new issues that have come to light and have gone unnoticed. The principal objective is a review of the working-class family budgets of the urban area of the Bilbao Estuary. We seek to verify the hypothesis of whether the working-class families in the critical inter-war period could afford the cost of living with the wages earned. However, it has been done by focusing on a specific date, the year 1924, for which we have a novel and original source of information. Furthermore, the study contemplates a complex urban geographical framework of great interest, namely the area of the Bilbao Estuary, which enriches the results and requires an adjustment of the analytical approach.

The article is structured into five sections. The first introduces the different documentary sources used and the methodology applied in each case; the second and third sections address the socio-economic and spatial context of the three municipalities selected - Bilbao, Getxo and Sestao-, together with a general characterisation of the socio-professional, population and wage structure derived from the municipal register of inhabitants of the period; the fourth section examines in depth a small database of day labourer families in their most critical and vulnerable phase (nuclear families with children under the age of fourteen), the structure of their income according to the life cycle of the breadwinners and the strategies employed to respond to the critical situation of the high family pressure (the maximum number of members vs the impossibility of increasing income); finally, the fifth section describes the costs associated with a basic consumption basket in accordance with the prices in Bilbao in 1925. The crossing of the results of these two final sections will allow us to respond to the initial hypothesis.

2. Methodology and sources

This article uses different information sources derived mainly from the municipal archives of the selected municipalities of Biscay (Bilbao, Getxo and Sestao), written documents and the press from the period. These sources offer relevant information on central aspects, such as the typical diet of the labourers, the type of working-class family, the declaration of day wages earned and the prices of the basic consumption items. They also provide testimonies regarding the overall situation of the day labourer population, with particular attention on housing in the Biscay context of the 1920s. This section describes in detail the principal documentary sources making up the nucleus of the novel results of the article, namely the municipal register of inhabitants of 1924, and the specific methodology used for calculating the daily wages that this documentation requires. To facilitate a more agile reading of the article, we have opted to describe this source and its methodology in this section, while the topics referring to diet; the prices of basic consumer products and costs and budgets of the working-class families are addressed in the fifth section.

2.1. The database of municipal registers of 1924

This study is based on the systematic analysis of three municipalities in the metropolitan area of the Bilbao Estuary in 1924; the capital, Bilbao, which was home to 140,722 inhabitants; Sestao, a characteristically working-class municipality on the left bank of the Estuary, with 15,243 inhabitants; and Getxo, located on the right bank where the families of the elite business class lived, with a total of 12,906 inhabitants. Altogether, the three municipalities represented 62% of the population of the metropolitan urban area, equal to 270,000 people.

The database generated for this research has been constructed through the computerisation and subsequent analysis of the family records of the municipal registers of Bilbao, Getxo and Sestao in 19243. For the case of Bilbao, a sample containing 34,954 inhabitants has been compiled, representing 24.8% of the total population. This Bilbao sample has two parts: one made up of residents in the working-class neighbourhoods4; and another that includes the inhabitants of other districts of the city, such as the suburbs and the old quarter5. In the case of Getxo, the data have been drawn from the complete population records in the municipal register of this year, accounting for a total of 12,893 inhabitants. For Sestao, a sample of 7,194 inhabitants has been used, representing 47.2% of the inhabitants of this municipality.

Finally, and with the purpose of verifying with greater precision our initial hypothesis, a new database has been elaborated, derived from the one described above for the three municipalities and restricted to a very specific sample: those families with a nuclear structure that only had children below the age of fourteen (the age prior to entering the labour market) and whose income, declared by the day labourer, did not exceed 13 pesetas per day6. These young families, with young children, lower daily wages and low-skilled jobs constituted the most vulnerable group of the urban spectrum on which this research is focused in order to analyse the extent to which they could have suffered from serious difficulties of subsistence.

The authors of this article have shown in their many publications both the virtues and weaknesses of using municipal registers as a single source7. On the one hand, in a positive sense, it allows the possibility of using individual and family socio-economic data and characteristics for the whole population, when this source is correctly elaborated by the municipal civil servants; and, on the other hand and in a less positive sense, there is a lack of uniformity derived from the self-declaration by each individual of their own data. In this specific case of the municipal registers of the year 1924, their use is justified by the particular feature of their overall quality with respect to other registers that we have been able to incorporate in our database, together with the inclusion of a new variable - the individually earned daily wages - which does not appear in any other census document. This new information allows us to draw novel conclusions in this article for the historiography regarding the professions and wages of all of the social groups that are not drawn from business sources of specific economic sectors, however representative they may be.

2.2. The calculation of the annual days worked in the declaration of annual salaries in the municipal registers

The principal unique feature of the 1924 population register is the inclusion of a field in which the breadwinner had to indicate the revenue or income received by each of the members residing in the household. This declaration is particularly valuable for historians as it is not usually included in the municipal registers and even less so with the almost universal coverage of Biscay.

The amounts declared are expressed in different formats: daily wage, weekly, monthly, quarterly or annual income. This has required the transformation and homogenisation of this information into the daily wage. In the case of weekly or monthly wages being declared, we have assumed the usual practice at the time in Spain of working six days per week, respecting the Sunday rest day8. The calculation becomes problematic when the data declared correspond to the annual wage, as there is no certainty as to the number of days worked per year in the different economic sectors and labour categories.

This issue has been subject to controversy, given that the differences between the periods, labour patterns, economic sectors and models and even meteorological factors have given rise to very diverse responses (Borderías and Muñoz-Abeledo, 2018: 98). In the case of the Basque Country, there is a certain level of consensus as to the consideration of a figure of 300 days worked per year. Ignacio Olábarri Gortázar (1978: 368) addresses this point in detail, highlighting the general compliance with the Sunday rest in Biscay from the beginning of the twentieth century, while the feast days were reduced to a minimum, resulting from a common request by the socialist unions as a strategy to increase the income of the workers. According to this author’s data for 1920, the majority of trades had achieved a reduction in feast days to between five and six per year, one on 1 May and the rest decided by the employers. This figures of 300 days per year is also sustained by Pérez Castroviejo (1992: 186) and, more recently, by Houpt and Rojo Cajigal (2023: 283) in their respective studies focused on industry in Biscay.

In order to confirm the previous figures and obtain new real data, we have compiled nominal and detailed information (day by day) of the pay checks of a sample of the workers of an iron and steel company in Bilbao, Santa Ana de Bolueta (STB) for the whole of the year 1924. This factory was the first in Bilbao to install a blast furnace (in 1841) and was located in the municipality of Begoña, an elizate (parish) adjacent to Bilbao in 1924 (Alonso Olea, Erro Gasca and Arana Pérez, 1998: 220-238). It was a medium-sized company among the industrial firms of Biscay, with a working-class labour force in the factory of between 150 and 160 people (Alonso Olea, 2001: 160-163).

According to the data extracted9, the company’s facilities were open all of the 366 days of that year (1924 was a leap year). The average number of days worked by the workers of the sample was 315, with a range fluctuating between 299 and 366 days, except for two people who were absent for between four and fifteen full weeks.

As a result, we consider that applying the average figure of 300 days worked per year is sufficiently justified for those workers who declare their annual daily wage in our database.

3. The Basque urban society: the Bilbao Estuary

The urban population in the Basque Country was traditionally small, accounting for only 10% at the end of the eighteenth century, compared to the 24% in Spain and 50% in regions such as Murcia and Andalusia (Reher, 1994: 25). This situation experienced a radical change with the industrialisation process in Biscay and Gipuzkoa from the mid-nineteenth century. In 1900, the Basque urban population represented almost 50% and in 1930 it was 66%, while the Spanish average remained at 37%.

The greatest growth occurred in Biscay, specifically in the urban agglomeration surrounding the Bilbao Estuary10. Between 1860 and 1930, this area experienced an economic, demographic and social transformation, consolidating into the principal industrial and urban centre of the north of Spain. This demographic boom was mainly driven by emigration. In 1930, the population of the area of the Estuary reached 304,364 inhabitants, as opposed to the 44,681 of 1860, converting it into one of the urban areas with the highest growth in mainland Spain (González Portilla and Beascoechea, 2000: 34-44).

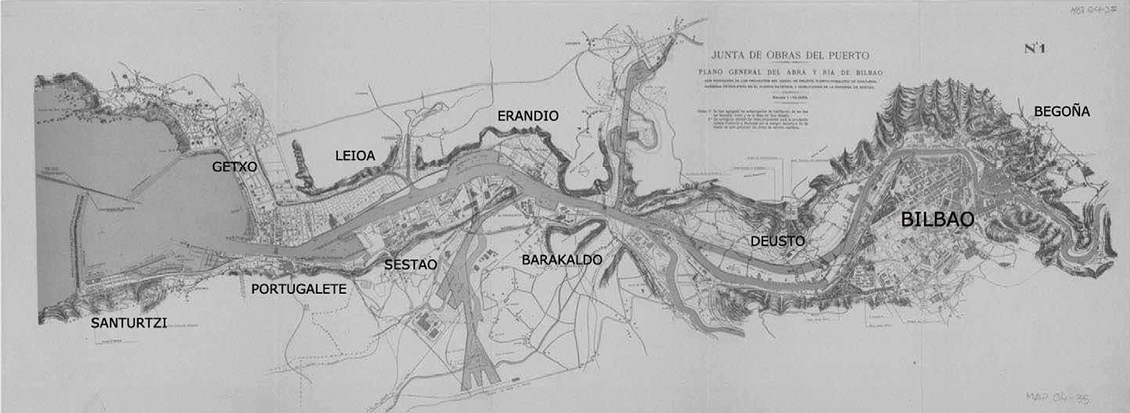

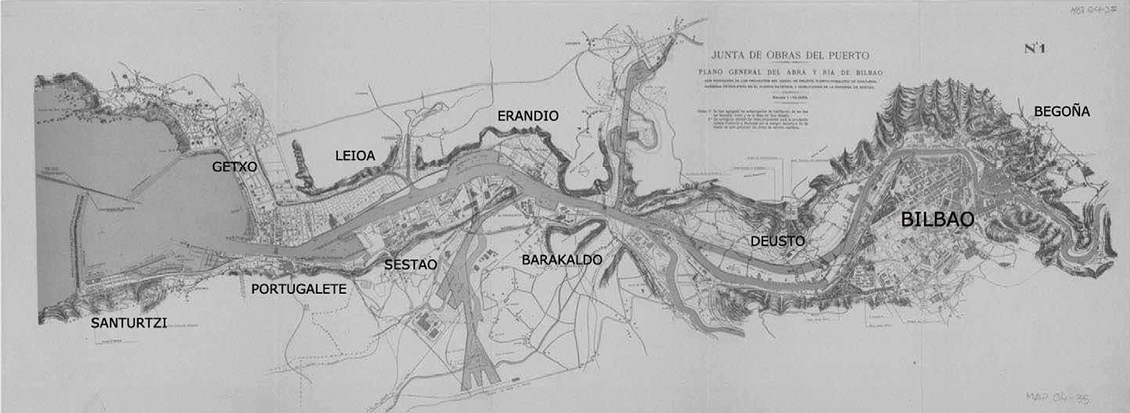

Figure 1: General map of the lower course of the Bilbao Estuary with the principal municipalities in the 1920s

Source: Own elaboration based on the Annual Report of the Works Council of the Port of Bilbao 1929.

The industry growth, based on heavy industry, mining and banking, consolidated the Estuary as a dynamic centre. Except for certain cyclical crises, this process expanded during the early decades of the twentieth century. The First World War boosted the industrial activity even further, particularly in iron and steel and naval construction, generating considerable economic profits and consolidating a powerful financial sector (González Portilla et al., 2001). The economic needs and business interests motivated the reorganisation of the metropolitan space, with the construction of infrastructures and factories throughout the Nervión Estuary. This urban space, whose central nucleus was Bilbao, expanded, incorporating several industrial nuclei that grew in accordance with the workforce required along the final fifteen kilometres of the Estuary.

The left bank experienced a rapid transformation towards an industrial landscape, with factory towns that expanded with no planning, dominated by improvisation and business interests. Sestao consolidated as the authentic “factory” of Biscay, housing large establishments such as La Vizcaya and the dockyards of La Naval. The working-class homes were built up the hill, interlacing with railway lines and mine loading docks, forming a dense and anarchical residential fabric. In 1930, the population of Sestao reached 18,335 inhabitants (González Portilla et al., 2001: II, 58-141).

On the right bank, industrial areas such as Erandio and Leioa also experienced growth, while Getxo, which initially began as a spa resort, from 1900, became the residential area of the business elite, with residential estates such as Neguri or Zugatzarte. The growing demand for personnel for services and construction in this town gave rise to the emergence of different groups of modest and medium-sized dwellings distributed throughout Algorta and Las Arenas. As a result, Getxo reached a population of 16,859 inhabitants in 1930 (Beascoechea and Zarraga, 2011).

As the principal population and services nucleus of the agglomeration, Bilbao led the development of infrastructures and marked the logic of social stratification in the urban area (González Portilla, dir., 1995). In 1900, the city had developed a strict social ranking of the urban space. In this way, Bilbao was divided into three areas: the working-class neighbourhoods, a residential suburb for highly skilled workers and a mixed historical centre. During the early decades of the twentieth century, this uneven structure was maintained, although with significant changes: the suburbs expanded, becoming the home to a growing middle class and the new services district, while a new working-class periphery emerged throughout the whole of the southern part of the city and the municipalities of Begoña and Deusto, which were annexed in 1925 (Beascoechea, Pareja and Serrano, 2017; Beascoechea Gangoiti, 2024).

4. Social structure and wage levels in 1924

Before examining the labour and wage conditions of the working-class families in greater depth, it is necessary to establish a general framework of the social, labour and wage characteristics of the group of towns in the area of the Bilbao Estuary on which our study is focused: Bilbao, Getxo and Sestao.

We seek to examine a series of fundamental conditions for understanding the internal concordances and differences between these urban nuclei. Specifically, we are referring to demographic aspects, such as the type of family and economic factors, including the sectoral distribution of the active population. Finally, we will analyse the social and professional composition and wage situation linked to this structure in the year 1924.

4.1. Types of families, origin and sectoral distribution

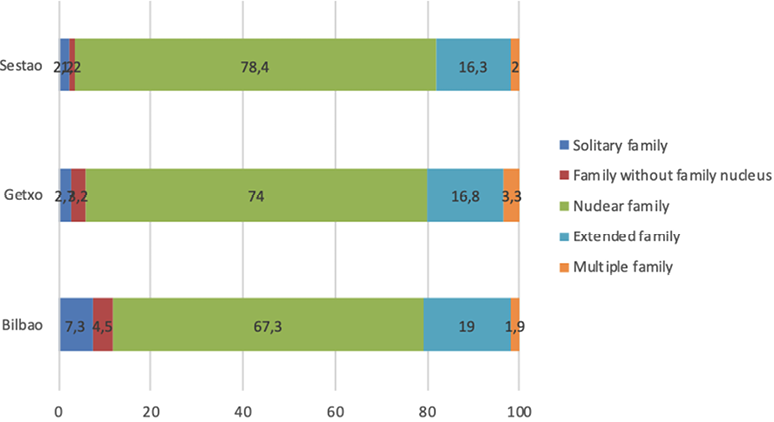

With respect to the forms of co-residence in the historical populations, the historiography has described a gradual evolution from a high predominance of complex family structures towards a greater relevance of nuclear families, a phenomenon that accompanied the transition from traditional agricultural economies to modern societies (Laslett, 1972). As we can observe in Figure 2, the nuclear families, formed only by parents and their children, that is, direct ties, were in the majority and accounted for between 67% and 78.4% in the municipalities of Bilbao, Getxo and Sestao in 1924.

However, the capital (Bilbao) had a slightly lower proportion of this type of family in comparison with Getxo and Sestao, with a greater weight of extended families (19%), which included other relatives in the residential unit11. It should be noted that in pre-industrial urban societies of the Basque Country, the way of living was, on the whole, nuclear12 and that the evolution from the Old Regime to the first third of the twentieth century in these urban societies consisted precisely in a slight loss of this nuclear nature in favour of extended families. Finally, in light of the results of the 1924 municipal register, there is no doubt that the study should focus the analysis of standards of living on the classic or nuclear type of family.

Figure 2: Structure of families (%) by household head (both sexes and all ages)

Source: Own elaboration based on samples from the Municipal Registers of Inhabitants of Bilbao (AMB-BUA), Getxo (AMG) and Sestao (AMS).

A second indicator with a high explanatory value is the sectoral structure of the active population. In this respect, the data of the register of inhabitants (see Table 1) confirm two issues indicated in previous studies. The first is the low rate of female activity: around 15% in Sestao, 27% in Getxo and 31% in Bilbao)13. In Biscay during the first third of the twentieth century, this was due both to problems of concealing the source and of the productive structure, which prioritised highly masculinized industrial sectors and greatly limited the employment possibilities of women. Furthermore, this type of employment was concentrated in the services sector, closely related to the weight of domestic service in Bilbao and Getxo (Pareja Alonso and García Abad, 2002: 316; Beascoechea, 2015: 162-165). The second indicator is the fully urban component of the three towns studied. Only in Getxo was a noteworthy percentage of the primary sector maintained, concentrated in the still rural part of the municipality (Andramari).

Table 1: Percentage of distribution of the active population (15-64) by economic sector and sex in Bilbao, Getxo and Sestao in 1924

|

Economic sectors |

Bilbao |

Getxo |

Sestao |

|||

|

% men |

% women |

% men |

% women |

% men |

% women |

|

|

Primary sector |

1.7 |

0.1 |

4.9 |

6.4 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

|

Secondary sector |

60.9 |

17.6 |

47.9 |

10.2 |

84.1 |

33.2 |

|

Tertiary sector |

37.4 |

82.3 |

47.1 |

15.7 |

66.8 |

|

|

Total active population |

8,951 |

4,278 |

3,054 |

1,299 |

2,110 |

331 |

|

Rate of activity |

87.1 |

31.0 |

85.5 |

23.7 |

92.7 |

15.7 |

|

Inactive and without profession |

1,331 |

9,535 |

517 |

3,267 |

167 |

1,777 |

Source: Own elaboration based on samples from the Municipal Registers of Inhabitants of Bilbao (AMB- BUA), Getxo (AMG) and Sestao (AMS).

Otherwise, the dominance of the secondary sector among the male individuals is evident, particularly pronounced in the case of Sestao. On the other hand, Bilbao, and particularly Getxo, displays more balanced rates between the secondary and tertiary sectors, which coincides with the results of other studies and indicates a clear change of trend which consolidated over the following years (Pareja, García-Abad and Zarraga, 2014: 153-154).

4.2. Socio-professional hierarchy and the wages of men and women

The central role of industry in the urban world of the Bilbao Estuary during the 1920s is directly reflected in the socio-professional structure of the population, classified according to the HISCLASS system (Table 2). However, beyond this, the specific features of its composition stand out, differentiated between the three nuclei analysed and the disparities between the activities declared by men and women.

Sestao is the paradigmatic case of a factory town connected to the large iron and steel and metallurgic companies. This means that almost 90% of the male human assets in manual work belonged to the low-skilled groups. Although the municipal register on the whole classes them as day labourers, as we shall see later in the article, this apparent low level of skills did not prevent this group from earning wages that were equal to or even higher than those of many qualified professions. This phenomenon reflects the specific labour characteristics of the epicentre of Biscay’s business immenseness (Ibáñez Ortega, 2011).

Table 2: Socio-professional structure of the active population (15-64) classified with HISCLASS by sex in Bilbao, Getxo and Sestao in 1924 (%)

|

HISCLASS groups |

Bilbao |

Getxo |

Sestao |

|||

|

% men |

% women |

% men |

% women |

% men |

% women |

|

|

Higher management and professionals (1-2) |

7.0 |

3.3 |

7.1 |

1.2 |

0.9 |

0.0 |

|

Lower managers and professionals, administrative and sales personnel (3-4-5) |

30.8 |

7.2 |

24.3 |

13.0 |

12.4 |

23.8 |

|

Foremen and skilled workers (6-7) |

11.4 |

4.3 |

16.7 |

2.6 |

3.5 |

5.4 |

|

Farmers and fishermen (8) |

0.4 |

0.1 |

2.4 |

2.4 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

|

Lower-skilled workers (9) |

7.6 |

8.8 |

10.5 |

6.4 |

5.7 |

11.4 |

|

Unskilled workers (11) |

42.8 |

76.5 |

35.6 |

70.5 |

77.3 |

59.3 |

|

Lower-skilled and unskilled farmworkers (10-12) |

0.1 |

0.0 |

3.5 |

4.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Total active population |

8,951 |

4,278 |

3,087 |

1,315 |

2,112 |

332 |

|

Inactive and without a profession |

1,332 |

9,535 |

484 |

3,251 |

165 |

1,776 |

Source: Own elaboration based on the Municipal Registers of Inhabitants of Bilbao (AMB-BUA), Getxo (AMG) and Sestao (AMS).

In contrast with this extreme model, Bilbao and Getxo enjoyed a more balanced situation, with a pronounced presence of highly qualified men and a large group of medium-level professionals, administrative and sales personnel. Although the manual workers continued to be dominant, the proportion of qualified workers was significant and those with no qualifications or a low level of education accounted for around half of the active male population. The only relevant exception is that of Getxo, where a considerable number of workers were connected to the agricultural world, as previously mentioned.

With respect to the female employment activities, the high percentage of unqualified workers is noteworthy. This reveals two different realities between the cities studied. In Bilbao and Getxo, where more than 70% of working women were employed in unskilled jobs, this was principally due to the high demand for female personnel for domestic service. The case of Getxo is extreme, as 97% of the women in this group worked as servants.

In Sestao, the unskilled female workers also constituted the largest group but far behind the levels of the previous cases; in the same group, the servants represented only a little over half of the total. On the other hand, a third declared themselves to be day labourers, although half of them were, significantly, single or widows. This factory town was also different due to its relatively high percentage of non-manual female workers, as many worked in small retail establishments or as teachers.

These results of the socio-professional structure take on a new dimension as they are complemented with the analysis of the average wage levels of the different socio-labour groups, both male and female, presented in Table 3. First, it is important to note that despite the differences existing between the three municipalities, the average wages of the male non-manual workers with a medium level of education were fairly homogeneous. This suggests a greater uniformity in the remuneration of administrative and sales workers. However, the wage differences were substantial between the higher management and professionals, particularly in Getxo, where the presence of Biscay’s business elite drove the wages of this group considerably higher.

Table 3: Average wage of the active population (15-64) by HISCLASS groups according to sex in Bilbao, Getxo and Sestao (pesetas/day)

|

HISCLASS groups |

Bilbao |

Getxo |

Sestao |

|||

|

men |

women |

men |

women |

men |

women |

|

|

Higher management and professionals (1-2) |

27.1 |

7.8 |

68.5 |

152 |

13 |

n/c |

|

Lower managers and professionals, administrative and sales personnel (3-4-5) |

13.5 |

4.8 |

12.2 |

5 |

12 |

7.4 |

|

Foremen and skilled workers (6-7) |

7.7 |

3.3 |

9 |

2.5 |

9.1 |

2.8 |

|

Farmers and fishermen (8) |

5.2 |

n/c |

8.2 |

n/c |

n/c |

n/c |

|

Lower-skilled workers (9) |

7.6 |

2.6 |

7.2 |

2.6 |

11.9 |

3.2 |

|

Unskilled workers (11) |

6.1 |

1.5 |

6.1 |

1.4 |

8.2 |

5.4 |

|

Lower-skilled and unskilled farmworkers (10-12) |

7.3 |

n/c |

5.5 |

2.9 |

n/c |

n/c |

Source: Own elaboration based on the Municipal Registers of Inhabitants of Bilbao (AMB-BUA), Getxo (AMG) and Sestao (AMS).

Note: n/c: no cases

In the case of the remunerations of the manual workers, the uniqueness of the labour market on the industrial left bank (principally Sestao and Barakaldo) can be clearly seen, where the nominal wages were much higher than those of the workers of similar categories of other areas. Comparing only the average data of Bilbao and Sestao, we can see that in the factory town the differences fluctuated between 18% (in the skilled workers group) and no less than 56% (in the low-skilled group).

Therefore, we analysed in detail the composition of HISCLASS group 9 (lower-skilled manual workers) in Sestao. This group is dominated by a large number of workers accounting for more than half of the total who declare themselves as “day labourers” and acknowledged a wage of 13 pesetas per day. The most congruent hypothesis is that the majority of these workers formed part of the workforces of the large iron and steel and naval factories, where the extreme demands for a high level of physical force and the ability to adapt to conditions of extreme heat and the danger of factory work were more important than qualifications (Ibáñez Ortega, 2011: 138-141). This situation can also be observed in other previous studies, such as those by González Portilla (1984), Fernández de Pinedo (1992), Pérez Castroviejo (1992 and 2006) and more recently in the studies by Houpt and Rojo (2023), which focus on the wages of workers with a medium level of qualifications in the large company Altos Hornos de Vizcaya.

Another exception related to the specific features of the local labour market is the high average wage recorded among the skilled manual workers in Getxo, very close to Sestao and clearly higher than that of Bilbao, with which it coincides in the rest of the categories. In this case, it was determined by the enormous weight of trades related to construction, principally bricklayers, carpenters and stonemasons. The residential construction was the principal economic activity of Getxo, which underwent a meteoric residential expansion to satisfy the demand for housing of the business and professional elite classes. This phenomenon can explain that the average daily wage of these trades was as much as 10 pesetas, similar to that of Sestao and much higher than that of Bilbao14.

On the other hand, in most of the socio-professional categories, female wages represented around a third of the male wages15. Furthermore, the low number of cases available makes their interpretation complex. The most relevant point is that of the low wages declared by the group of unskilled female workers, both in Getxo and in Bilbao, derived from the afore-mentioned weight of domestic service. Sestao was a relative exception, as the percentage of servants was much lower and the wages of the female day labourers were considerably higher.

Finally, we conducted a new analysis of the occupational structure, this time identifying the most frequent Minor Groups of the HISCO classification among the active male population. To do this, exclusively for this point of the study, we merged the declarations of the three municipalities of the study and reflected the groups for which there are more than one hundred cases. In this way, we have been able to obtain an overall view of the weight of the different occupations, the direct comparison of the different wage ranges and the diversity of the degrees of dispersion.

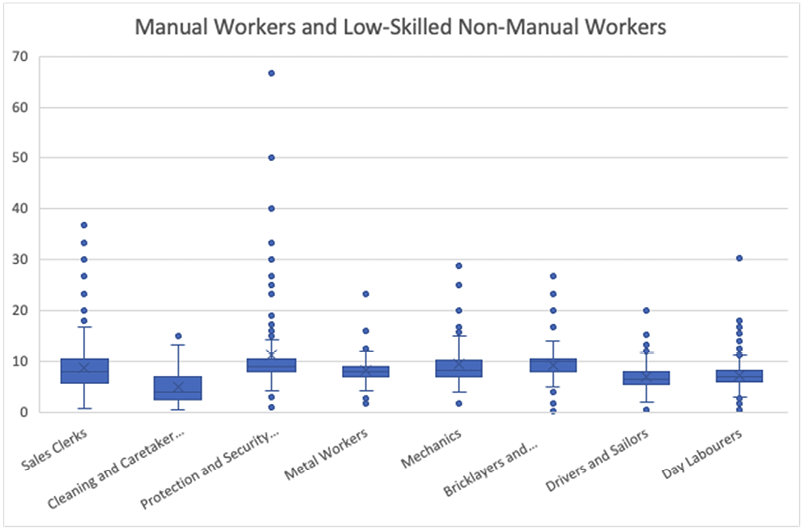

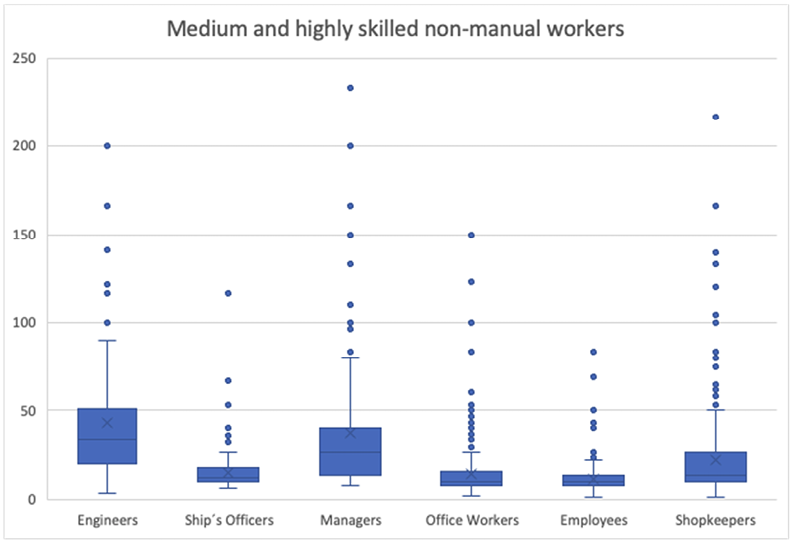

The data in Figure 3, which reflect this information, enable us to qualify certain situations previously mentioned. One of the most evident is that among the manual workers, the dominance of the day labourers was overwhelming. They accounted for 82.9% of the total declarations of the five most frequent groups, with more than 4,000 cases. Far behind, with 7.5%, were the construction-related trades, particularly represented in Getxo and Bilbao. On the other hand, among the groups of non-manual workers of over one hundred cases, we can observe wide variations with up to nine different groups. Among the first nine groups, the employees and office workers represented 35%, followed by traders and sales clerks with 30%, while the highly skilled group (managers, engineers and ship’s offices) represented almost 20%.

The figure also provides a first view of the wage ranges and their dispersion within the most frequent trades. Due to the large differences between these two components, depending on the skill level, we divided them into two groups; manual workers and low-skilled non-manual workers, and medium and highly skilled non-manual workers.

The first group displays a high level of equality in the wage ranges. They fluctuate between a little under 5 pesetas for cleaning and caretaker services, to around 7 pesetas per day for sales clerks and drivers / sailors, and between 8 and 10 pesetas for the rest. On the other hand, the wage dispersion displays some differences: it was lower in the manual trades (with standard deviations of between 1.8 and 3.9) than in the low-skilled non-manual occupations, where the standard deviations fluctuated between 1.7 and 5.

In the case of the non-manual workers, there were also large differences between those with a medium skill level such as office workers with daily wages of around 10 pesetas and standard deviations higher than 5; and shopkeepers and marines, whose average wages were higher than 14 pesetas with high standard deviations of between 6 and 12. The two most highly skilled groups, engineers and entrepreneurs/managers were a different case, with average remunerations of 32/33 pesetas and very high deviations.

Figure 3: Wage range and dispersion of the principal groups of male occupations according to HISCO Classification (sum of Bilbao, Getxo and Sestao) in 1924

Source: Own elaboration based on samples from the Municipal Registers of Inhabitants of Bilbao (AMB-BUA), Getxo (AMG) and Sestao (AMS).

5. The working-class families of the Estuary, socio-professional characterisation and wage situation

As already explained in the methodology section, based on the use the source of the municipal register, we have created a new sample with more selective criteria in the search for a less professionally qualified “type of working-class family” with very low incomes and in the critical stage of their life cycle in which the maximum number of adults and minors lived in the same family unit. This sample of young families displays a high level of homogeneity in terms of occupation (they mostly declared themselves as day labourers), they had a nuclear and large family structure (with children under the age of fourteen) and had an income of no more than 13 pesetas per day16. Hereafter, we will work with a purely working-class database made up of a total of 13,427 people and 2,851 families. The breadwinners were mostly men in the municipalities of Getxo and Sestao. Only in Bilbao can we find a significant number of widows with dependent children who worked to sustain their families (6.3%).

As could be expected, Table 4 shows that the group of families of unskilled workers were in the majority. Those with an undefined occupation and recorded only as earning a “daily wage” are difficult to classify and have lower wages in the three municipalities. However, the distribution seems to be uneven in terms of the type of municipality: the proportion is the highest in Sestao, a purely working-class town (84.6%), slightly lower in Bilbao (62.9%) and lowest in Getxo (40.7%). On the other hand, when we observe the groups on the higher part of the social scale, the high presence of administrative and sales personnel and skilled manual workers in Getxo is noteworthy (together accounting for 43%). This group is slightly more relevant than the unskilled population. A large number of retail and administrations workers also resided in Bilbao, typical of a regional capital with centralised services provided to the whole metropolitan area (16.9%).

Table 4: Socio-professional structure of the working-class families classified by HISCLASS in 1924 (household heads aged over 25 years, both sexes)

|

HISCLASS groups |

Bilbao |

Getxo |

Sestao |

||||||

|

Num |

% |

Average daily wage |

Num |

% |

Average daily wage |

Num |

% |

Average daily wage |

|

|

Administration and sales personnel (4-5) |

291 |

16.9 |

7.8 |

100 |

15.9 |

8.3 |

21 |

5.1 |

8.4 |

|

Skilled workers (7) |

221 |

12.8 |

7.7 |

170 |

27.1 |

9.2 |

15 |

3.7 |

9.4 |

|

Farmers and fishermen (8) |

10 |

0.6 |

4.1 |

19 |

3.0 |

6.2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Lower-skilled workers (9) |

119 |

6.9 |

6.5 |

83 |

13.2 |

8.2 |

27 |

6.6 |

11.6 |

|

Unskilled workers (11) |

1,084 |

62.8 |

6.5 |

255 |

40.7 |

6.9 |

347 |

84.6 |

8.6 |

|

Total active population |

1,725 |

627 |

410 |

||||||

|

% women household head |

6.3 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

||||||

Source: Own elaboration based on samples from the Municipal Registers of Inhabitants of Bilbao (AMB-BUA), Getxo (AMG) and Sestao (AMS).

It is noteworthy that the average wage level displays a highly variable arc depending on the different socio-economic and residential specialisation of each municipality, even within the same socio-labour groups. It is necessary to consider that in the municipal registers, the subjects themselves are those who name their profession (the majority declare themselves to be “day labourers”), which does not allow us to differentiate the specialisation and category within the firms, the size of the company or the economic sector (mines, metallurgy, craft professions, etc.). For example, the unskilled workers in Sestao declared that they earned two pesetas more per day on average with respect to the same categories of the Bilbao day labourers. The case of the low-skilled workers is similar, who, although accounting for only a small percentage, were earning around 5 pesetas more per day in Sestao than in Bilbao and 3 pesetas more than in Getxo. These wage differences within the same professional groups depending on the municipality of residence, corresponding to a very different economic activity, constitute a novelty in the Biscay historiography, which, to date only acknowledges substantial wage differences in accordance with the professional category and seniority. However, these data show us another view whereby the place of residence of the day labourers could mark the difference between families who were on the poverty line and those who could have a certain savings capacity. This was true even for those living in towns just a few kilometres away from each other.

5.1. Working-class families and their life cycle and daily wage by age

It is a well-known fact that examining the life cycle by age in families facilitates the identification of the most critical moment in which they must strike the maximum balance between the daily wage earned and the maximum number of minors in the household. There are moments of maximum pressure when there are more mouths to feed and less possibilities to increase income, particularly if the wives had serious difficulties to become employed in anything other than domestic work and raising the children until they finished school (between 12 and 14 years of age), after which they could join the labour market, although not always with paid work (apprentices, assistants, etc.).

Table 5: Average number of children, type of family and average daily wage according to the age groups of the household heads (both sexes, over the age of 25).

|

Average number of children |

|||

|

Age groups |

Bilbao |

Getxo |

Sestao |

|

25-29,9 |

1.6 |

1.8 |

1.9 |

|

30-34.9 |

2.1 |

2.4 |

2.5 |

|

35-39.9 |

2.8 |

3.2 |

3.1 |

|

over 40 |

2.8 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

|

Average |

2.4 |

2.6 |

2.7 |

|

Average daily wage |

|||

|

Age groups |

Bilbao |

Getxo |

Sestao |

|

25-29.9 |

6.8 |

7.8 |

8.6 |

|

30-34.9 |

6.9 |

7.9 |

9.0 |

|

35-39.9 |

6.9 |

8.0 |

8.8 |

|

over 40 |

6.7 |

7.8 |

8.7 |

|

Average |

6.8 |

7.9 |

8.8 |

|

Proportion of nuclear families |

|||

|

Age groups |

Bilbao |

Getxo |

Sestao |

|

25-29.9 |

85.5 |

73.0 |

81.8 |

|

30-34.9 |

79.9 |

87.1 |

80.7 |

|

35-39.9 |

78.8 |

79.2 |

81.3 |

|

over 40 |

83.6 |

85.3 |

83.1 |

|

Average |

84.4 |

81.5 |

81.6 |

Source: Own elaboration based on samples from the Municipal Registers of Inhabitants of Bilbao (AMB-BUA), Getxo (AMG) and Sestao (AMS).

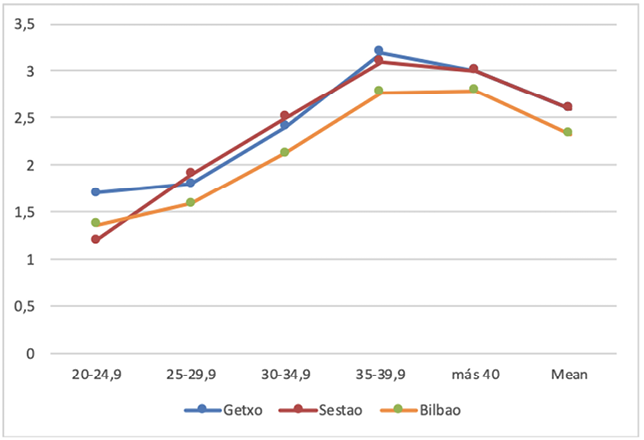

Figure 4: Average number of children and average daily wage according to the age groups of the household heads (both sexes, over the age of 25)

Average number of children

Daily wage

Source: Own elaboration based on samples from the Municipal Registers of Inhabitants of Bilbao (AMB-BUA), Getxo (AMG) and Sestao (AMS).

Once again, we should indicate the differences in the reality of the working-class families depending on the place of residence within the metropolitan area. The average number of children in general of the families of the three municipalities was close to three children, being lower in Bilbao (2.4) and higher in Sestao (2.7) and Getxo (2.6). Therefore, the fact that the daily wages were more precarious in Bilbao than in Sestao is not surprising, with Getxo holding an intermediate position between the two. We could establish the hypothesis that a lower wage would lead to patterns that show a greater awareness of birth control, for example, in Bilbao with respect to the other two municipalities. However, we should also consider other variables that influenced these decisions, such as fertility cultures of the places of origin and the possible difficulties to find and pay for accommodation.

In the light of our data, there is no doubt that the most problematic moment during life is when the breadwinners were aged between 35 and 40 years old. It is during this period when the maximum number of young children was in the family unit coinciding with a slight increase in the income earned by the breadwinners at that age. However, this increase was not sufficiently relevant to alleviate this difficult family situation as the increase in the daily wage was not even one peseta, while the number of members in the family unit had doubled (see Table 5 and Figure 3).

This is probably one of the decisive reasons why, in this specific age group, families became less nuclear than at any other moment in their life cycle, modifying their structure to extended families. This family adaptation would enable the incorporation of guests or other relatives as a strategy to increase income temporarily to respond to the misalignment between income and the number of individuals in the family, particularly around the age of 35-40 years old.

Table 6: Breadwinners forming extended families (Gr 4) by age group (%)

|

Age groups |

Bilbao |

Getxo |

Sestao |

|

25 -29.9 |

14.8 |

32.2 |

16.0 |

|

30 -34.9 |

32.6 |

22.6 |

30.7 |

|

35 -39.9 |

28.4 |

30.4 |

32.0 |

|

Over 40 |

21.5 |

13.9 |

18.7 |

|

% average |

18.4 |

18.5 |

18.4 |

Source: Own elaboration based on samples from the Municipal Registers of Inhabitants of Bilbao (AMB-BUA), Getxo (AMG) and Sestao (AMS).

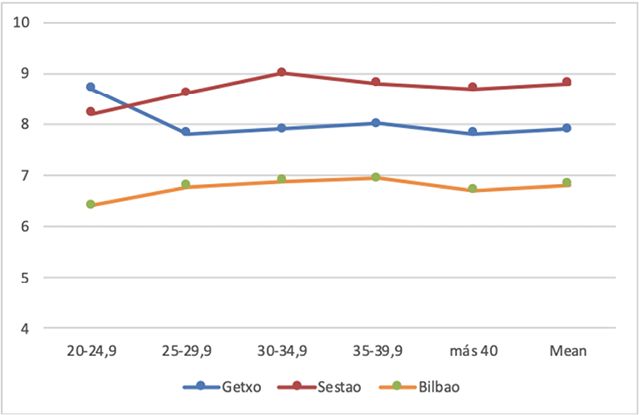

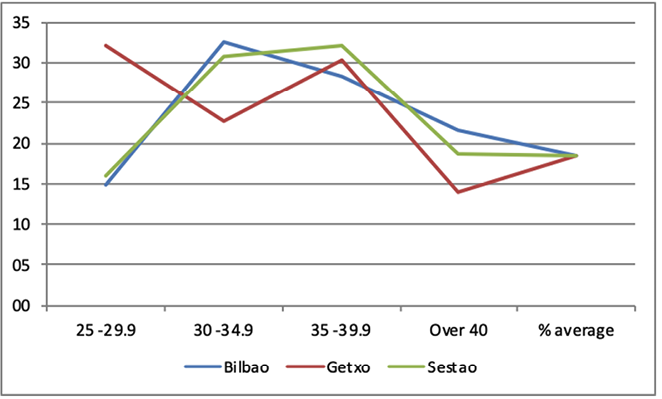

Figure 5: Breadwinners forming extended families (Gr 4) by age group (%)

Source: Own elaboration based on samples from the Municipal Registers of Inhabitants of Bilbao (AMB-BUA), Getxo (AMG) and Sestao (AMS).

As we can observe in the figure, in the three municipalities, the proportion of extended families, which, on average was 18% of total families, precisely between the ages of 30 and 39, was above the average (more than 30% in the three municipalities). The fact that at the beginning and end of the life cycle of the families, the presence of relatives was below the average indicates that this strategy was circumstantial for the families and due to need. This strategy was abandoned when the pressure between the number of people and resources allowed. This situation was beneficial for both the host families who received additional help and income and for the recently arrived relatives, who could not afford accommodation despite having a job.

5.2. Responding to the impossibility of a double income in the regular market: strategies and alternatives

The wives of these types of working-class families in the three municipalities analysed mostly declared their occupation as “housewife”. It is well known that the census and municipal register sources systematically concealed the work of married women (Pérez-Fuentes, 1995; Borderías, 2006; Humphries and Sarasúa, 2012). The percentage of married women who declared their wages in our sample was 1.3% in Bilbao, 0.5% in Getxo and 0.3% in Sestao, very low numbers although this is not surprising. Due to the difficulty to conduct an additional exercise in this research to attempt to reconstruct the hidden work carried out by married women, which was probably seasonal, by hours and in the informal services market, we are inclined to believe that the possibility of a double income of the two spouses in the regular market was very low. This was even more the case when the women in our sample had young dependent children at that time of their lives. This was the contrary to other European industrial contexts in which the installation of factories with a mostly female workforce, mainly in the textile sector, gave rise to the possibility of married women being employed as workers and, therefore, contribute an income to the family. This has been shown to be the case in Catalonia (Borderías and Ferrer, 2015) and the Basque Country, mainly in Errenteria –Gipuzkoa-, and in municipalities of Biscay, such as Balmaseda (Moya and Pareja, 2018). However, in labour contexts related to mining and steel and metallurgic production, factory work options for women were practically non-existent.

The difficulties for wives to contribute monetary income to the family, due to the problematic stage of the life cycle as they were raising small children, led them to resort to two alternatives that were also feasible to guarantee the survival of the group at critical moments. The first consisted in introducing relatives and guests into the home to live with the family; the second, sharing the rented dwelling with other families to reduce expenditure on this budget item, which could be very costly taking into account the shortage of working-class housing in these years, particularly in the case of Bilbao.

Table 7: Percentage of residents in the working-class households, related or otherwise (both sexes)

|

Residents |

Bilbao |

Getxo |

Sestao |

|||

|

Num |

% with a wage |

Num |

% with a wage |

Num |

% with a wage |

|

|

Relatives* |

451 |

23.1 |

141 |

20.6 |

105 |

22.9 |

|

Guests |

142 |

53.5 |

39 |

51.3 |

62 |

72.6 |

*Close and distant relatives.

Source: Own elaboration based on samples from the Municipal Registers of Inhabitants of Bilbao (AMB-BUA), Getxo (AMG) and Sestao (AMS).

The first alternative mentioned the incorporation of the relatives of the spouses and guests, seemed to be a commonly used strategy. As we can observe in Table 7, the relative option was preferred over guests, hence the frequency of the presence of extended families in the family structures. Among the relatives, there was a predominance of single women, which is an interesting option for the wives even though their mothers/mothers-in law and sisters/sisters-in-law did not contribute any income. Their presence helped ease the heavy domestic workload, allowed the wives to carry out occasional or hourly jobs outside of the home and the relatives could help with the homeworking in certain sectors such as dressmaking. If these relatives were young men, they could contribute some of their wages, similar to a guesthouse situation.

On the other hand, the guest option, which did not modify the family structure, was particularly relevant in Sestao, but also significant in Bilbao and Getxo. In this case, there was a predominance of single men, although it was not unusual to find women among the guests who declared a profession and a wage. Both of these options were beneficial for both parties, as they constituted a solution to the difficulties of low wages and the shortage of housing.

Table 8: Number and proportion of families who reside in each dwelling in the working-class neighbourhoods of Bilbao

|

Number of families |

Num |

% |

Average family per dwelling |

|

1 |

407 |

25.6 |

|

|

2 and more |

1,181 |

74.4 |

|

|

Total families |

1,588 |

2.4 |

Source: Own elaboration based on the analysis of the districts of Bilbao la Vieja and La Estación, with a sample of 6,124 individuals. Municipal register of inhabitants of Bilbao (AMB-BUA).

The second alternative, which of several families sharing the dwelling as subtenants, has been mentioned in different studies on the period as a probable hypothesis, echoing the stories in the newspapers or reports on the working-class condition, rather than being based on data that could confirm this affirmation. For this study, an estimate has been made, based on the municipal register of 1924, in which we have analysed the space under most pressure in the Bilbao working-class neighbourhoods to distinguish whether there had been several families residing in the same dwelling and with what frequency. As we can observe in Table 8, almost 75% of the dwellings were shared by two or more families, with the average being almost three families17. This could mean that each family nucleus occupied a room, sharing the kitchen and bathroom and the payment of the rent, which was reduced by half or more. Therefore, the commonly reported overcrowding in the sources of the period would be due to a fundamental strategy to enable the working-class families to adjust their budgets and to guarantee subsistence at difficult times.

6. The trajectory of the expenditures of working-class families in the Bilbao area 1914-1924: the critical decade

The analysis of the cost of living of the working-class families in the region of Bilbao has been fundamentally addressed using two sources: the Municipal Statistical Gazette of Bilbao and the Reports of the Institute of Social Reforms, which provide retail prices of products consumed by the working class. The first source contains a broad series that enables us to determine the basic structure of the expenditures throughout the first third of the twentieth century, specifically from 1913 to 1939, also providing maximum and minimum housing prices18. The second includes the behaviour of the prices of basic necessities for the working class on different dates and representative towns of the industrial area of Bilbao (Bilbao, Deusto, Sestao and Barakaldo). The data extracted from these sources have been completed with information from certain records of the Industrial and Mercantile Centre of Biscay and those provided by the Provincial Board of Subsistence and the Civil Government of Biscay.

By analysing this documentation, we have been able to estimate the part of expenditure related to two large sections: food articles and housing and the home, with the latter being broken down into fuel and soap, without including the supply of water. However, the sources do not allow us to quantify the expenditure on “clothing and footwear”, which is only mentioned once, nor the section named “other expenses” or “miscellaneous costs”, which includes broad concepts difficult to define (such as hygiene, schooling, transport, leisure, etc.). In short, it is complicated to quantify and evaluate these sections given the lack of specific historical information.

With regard to the trajectory of expenditure, we should refer to the precedent of the intense inflationary process that characterised the Spanish economy during the war cycle between 1914 and 1921. After a brief period of deflation between 1921 and 1923, the economy experienced a process of stabilisation (Maluquer de Motes, 2013: 64; 69-70). During the years of the global conflict, consumer prices in Spain accelerated as a whole although with differentiated behaviour. Food prices increased significantly, as did domestic costs, but even more so those of clothing and footwear. However, the price of electric fluid remained stable and the rents of housing displayed a less inflationary behaviour. The latter remained stable until the end of the war, but from 1921, rents rose above the price of food, particularly between 1924 and 1925, when substantial increases in the average cost of housing were recorded (Maluquer de Motes, 2013: 71-72).

6.1. The “hunger wages” and the high cost of living during the inflationary period

In the urban area of Bilbao, the exceptional economic situation caused by the First World War fuelled what became constant protesting of the working classes. That is, protests against the price of basic necessities and the lack of affordable housing. Both of these problems dominated the social debate, which was transferred to the political sphere, becoming one of the principal fields of action of Bilbao’s city council (Beascoechea and Serrano, 2024).

With respect to the level of consumer prices, we should consider the conjunction of two factors; on the one hand, the severe increase in prices that was triggered during the years of the global conflict, with significant inflationary growth recorded between 1915 and 1920 and, on the other hand, the repercussion of the tax on consumer goods in the domestic economy. Basic articles were taxed by this highly criticised consumer tax, which, for the territories under a common regime, was abolished by the Law of 12 June 1911 that established a transitory period until 1920 (Martorell Linares, 1995).

That said, this law was not applied in the territories with a concerted regime19, so in Biscay a consumer tax collected by the provincial government coexisted with another one collected by the local governments of the province. In 1918, the provincial government of Biscay abolished the tax on basic necessity goods but maintained the tax on alcoholic drinks, industrial and luxury products as they brought in high profits for the municipal coffers that were difficult to replace.

During the years of the First World War, the protests against the prices of basic articles and, in general, against the high cost of living intensified, due to the serious repercussions on the budgets of working-class families. The socialist councillor of Bilbao’s city council, Felipe Carretero, calculated the tax on consumer goods during the campaign for the municipal elections of 191520.

Within this context of social crisis, protests and mobilisations, in May 1916, union representatives brought to the president of the Industrial and Mercantile Centre of Biscay the petitions that they had made to the employers of the metallurgic industries to combat the high cost of living, the abnormality of the circumstances and the future full of misery that would ensue21. To support their arguments, they referred to the statistical summary of what a typical working-class family made up of five individuals (spouses and three children) consumed each week in 1914 before the war and in 1916.

Table 9: Weekly list of the amount consumed by a working-class family (prices in pesetas)

|

Consumer articles |

Weekly amount |

Unit price 1914 |

Unit price 1916 |

Expenditure 1914 |

Expenditure 1916 |

|

Common oil |

1 kg. |

1.30 |

1.45 |

1.30 |

1.45 |

|

Bread (2 kg loaves) |

7 loaves |

0.80 |

1.00 |

5.60 |

7.00 |

|

Sugar |

1 kg. |

1.00 |

1.25 |

1.00 |

1.25 |

|

Rice |

¾ kg. |

0.50 |

0.60 |

0.35 |

0.45 |

|

Beans |

1 ½ kg. |

0.50 |

0.70 |

0.75 |

1.20 |

|

Cod |

1 kg. |

1.45 |

1.95 |

1.45 |

1.95 |

|

Electricity |

1 month |

3.00 |

3.15 |

0.75 |

0.80 |

|

Tomato |

2 tins |

0.25 |

0.35 |

0.50 |

0.70 |

|

Pork fat |

1 kg. |

2.00 |

2.40 |

2.00 |

2.40 |

|

Chickpeas |

1 kg. |

0.95 |

1.05 |

0.95 |

1.05 |

|

Lentils |

½ kg. |

0.50 |

0.75 |

0.25 |

0.40 |

|

Potatoes |

6 kg. |

0.15 |

0.30 |

0.90 |

1.80 |

|

Meat |

1 kg. |

½ 0.70 |

0.90 |

1.40 |

1.80 |

|

Soap |

1 kg. |

0.65 |

0.85 |

0.65 |

0.85 |

|

Salt |

1 kg. |

0.05 |

0.10 |

0.05 |

0.10 |

|

Coal |

½ qq. |

2.20 |

5.00 |

1.10 |

2.25 |

|

Weekly expenditure 1914 |

19.00 |

||||

|

Weekly expenditure 1916 |

25.45 |

Source: AHFB-BFAH. CIM 0006/012.

That is, if a labourer earned a weekly wage of 30 pesetas, he had to spend 25.45 pesetas on food and household expenses. With the remaining 4.55 pesetas, he had to pay for essential items, such as rent, water, clothing and footwear or medicine. These minimum expenses considered in this list increased by 33.95% between 1914 and 1916. In short, if it was impossible to live with a daily wage of 5 pesetas 22, living with the 3.50 pesetas that the majority earned, who also had more than three children, was unbearable.

Products such as sardines, eggs and milk were absent from this list. Specifically, eggs were an expensive food, and their price rose considerably in the dates mentioned23. This working-class diet, therefore, was far removed from an appropriate diet for workers in jobs requiring a large amount of energy typical of the Bilbao industrial context, where many workers were employed in the iron and steel or metallurgic sectors, naval construction, mining, port loading and unloading. The same is true for a family with a widowed working mother taking care of the home and sustaining her children.

This was a diet that could be classified as “subsistence against hunger”. Certainly, it was not designed to meet optimal dietary needs and we can understand that these families were resorting to basic foods and low levels of consumption as their wages did cover the cost of living24.

According to the data and testimonies consulted, we can confirm that during this specific period, the typical working-class families described above, that is, five members and a single income from one male wage, could not cover the most basic daily energy basket, which affected the well-being of the whole family group.

6.2. The price of housing as a conditioning factor of the expenditure of working-class families

After the First World War, consumption price stability was restored, which led to the stabilisation of the labour market and wage adjustments (Maluquer de Motes, 2013: 55; 71-72). The stability of transport, electricity and housing prices had contributed to softening the intensity of inflation during the war, after which, the rents began to rise gradually, increasing above food prices.

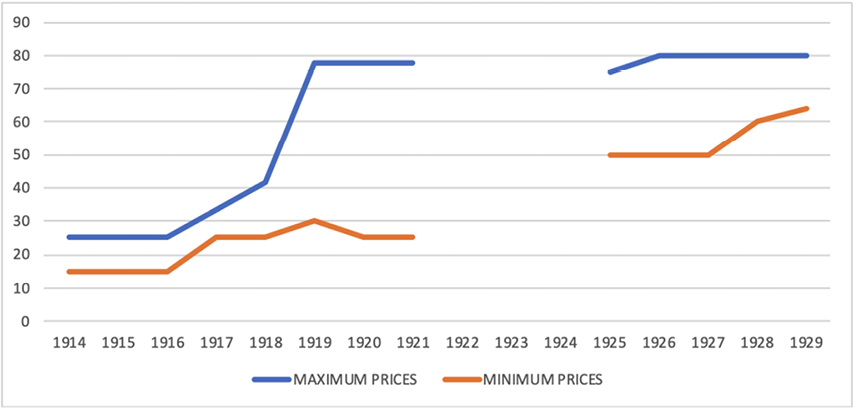

The housing rental price undoubtedly constituted the principal factor that conditioned the budgets of working families in the Bilbao urban area during the 1920s. By using the series of housing rental prices to reconstruct the Statistical Gazette of Bilbao, we can observe a similar dynamic to the rest of Spain. The increase in prices peaked in 1919 and they remained high until 1921 (77.5 pesetas/month). Subsequently, minimum prices were also affected (50-64 pesetas/month) until the end of the decade.

Figure 6: Evolution of the monthly working-class housing rental price in Bilbao 1914-1929 (pesetas)

Source: The Gazette was not published in 1922 and data were not recorded in 1923 and 1924. Statistical Gazette of Bilbao City Council (AMB-BUA).

In the Bilbao urban area, the housing problem had become serious from the beginning of the twentieth century and was closely related to the strong demographic growth of the previous twenty-five years, driven, undoubtedly by immigration. The latter contributed to doubling the population of Bilbao and multiplying fourfold the population of the mining and industrial area on the left bank of the Estuary (González Portilla et al., 2001: 95). The immigrant workers would have resorted to subletting rooms and cohabitation, as we have shown in the previous section, which led to overcrowding and a huge impact on the urban living conditions in the most affected areas.

The supply of affordable housing did not, in quantitative or qualitative terms, meet the needs of an expanding urban population (Azpiri, 2000: 230-233; Domingo, 2005; Muñoz, 2024). In the critical years of labour conflicts and demonstrations, the workers’ protests called for the regulation of tenancies, obliging landlords to respect the prices prevailing in 1914 and for the promotion of affordable rents.

In conclusion, we should indicate that the price of working-class housing rents in Bilbao had tripled with respect to 1914, from 300-180 pesetas/year, to 900-600 in 1925. The price of cheap housing rents also increased. This rise was associated with the strong demographic growth in Bilbao between 1920 and 1924 and the increase in demand, which had a significant impact on family budgets. According to our results with respect to the list of daily expenses of Bilbao working-class families in 1924, housing represented 17.4% of the total, a considerably higher percentage than the 9.8% recorded in the distribution of expenses of Spanish families in the same period studied by Maluquer de Motes (2013: 41).

7. Did the working-class budgets allow families to make ends meet?

Taking the average daily wage as a base, obtained from the municipal registers of inhabitants of Bilbao, Getxo and Sestao, we have calculated the maximum optimum quantity that could be spent on each expense group by unskilled workers in our area of study. As we can see in Table 10, the results reveal the scale in the expenditure possibilities of these workers in the area of the Bilbao Estuary, with the highest being those of the workers of Sestao. Below, we analyse the different realities, comparing these optimum hypothetical amounts with the expenditures drawn from the sources consulted.

Table 10: Estimate of the maximum budget that could be spent on each group of expenses of the unskilled working-class families with under-age children in Bilbao, Getxo and Sestao with respect to their daily average wage in 1924

|

Concepts |

% Costs * |

Bilbao |

Getxo |

Sestao |

|

Food |

66.4 |

4.32 |

4.58 |

5.71 |

|

Housing |

9.8 |

0.64 |

0.68 |

0.84 |

|

Household Expenses |

10.9 |

0.71 |

0.75 |

0.94 |

|

Clothing and Footwear |

6.1 |

0.40 |

0.42 |

0.52 |

|

Miscellaneous Expenses |

6.8 |

0.44 |

0.47 |

0.58 |

|

Average Wage (Pts) |

100 |

6.5 |

6.9 |

8.6 |

Source: Own elaboration base on the Municipal register of inhabitants of Bilbao of 1924 (AMB-BUA).

* Estimate of the different groups of expenditure obtained from Maluquer de Motes (2013: 41).

If we consider the daily food basket proposed by Borderías and Muñoz-Abeledo (2018: 97), adapted to the habits of the area of study25, the daily cost would be 6.12 pesetas, to which we must add the expenses of rent at 1.67 pts.26. Therefore, in both chapters the estimated maximum expenditure amount is exceeded in all three cases analysed. If we add the above household expenses (0.55 pts.), clothing and footwear (0.58 pts.) and other miscellaneous expenses (0.67 pts.), a total of 9.59 pesetas per day would be necessary to guarantee survival.

With respect to Bilbao, the result can be extrapolated to the case of the low-skilled workers who earned an average daily wage of 6.5 pts. In other words, the lowest wage if we compare it with that earned by the workers in Getxo and Sestao in the same professional category. This group is also that with low or no skills, representing 69.7% of all working-class families in Bilbao, a large group that was clearly unable to afford the daily expenses and, therefore, lived on the poverty line. Moreover, even more striking is that not even the skilled workers in Bilbao and/or the administrative and sales personnel could afford the estimated costs given the average daily wage corresponding to their professional category, 7.7 pts. and 7.8 pts, respectively. The consequences worsened given that they affected the broad professional spectrum of Bilbao’s working class labourers. As a result, we are able to definitively say that the unskilled working-class families who lived in the three Biscay municipalities of Bilbao, Getxo and Sestao did not have the capacity to cover the necessary daily expenses with their daily wage.

8. By way of conclusion

This article seeks to contribute to the classic debate in the European historiography regarding the situation and evolution of the quality of life and well-being of the working-class population as a result of the modernising process of industrialisation. To do this, we have reconstructed the wages and expenses in order to obtain an estimate of the budgets of urban working-class families with dependent children in 1924 in the metropolitan area of the Bilbao Estuary. Three municipalities have been studied: the residential town of Getxo, the industrial town of Sestao, both located in the mid and final sections of the Estuary and the working-class population residing on the periphery and new suburbs of the town of Bilbao.

It takes a new approach based both on a geographical perspective and the use of other information sources to which we have applied new socio-professional classification methodologies, such as the calculation of diets and expenses, giving rise to significant results for the Basque and Spanish historiography. Therefore, the classical literature focuses on the analysis of the always scarce company sources related to the workers’ daily wages, which has obtained relevant results. However, they ultimately reduce our knowledge to a specific industrial sector and even to the same controversial “case study”, however significant it may be in the new industrial areas. The reuse of an already known documentary source such as the municipal register of inhabitants of 1924, which, for the first time requests the whole resident population for information about the wage/daily wage, has enabled us to study all of the socio-economic groups independently of the company for whom they worked, their social class and their professional category in a broad residential space of metropolitan Biscay. The breadth of the population sample used in these three municipalities, selected as models of the new urban reality in the Basque Country, has allowed us to obtain conclusions of great historiographic interest in terms of two fundamental aspects. On the one hand, the considerable difference in wages that the low-skilled day labourers, who were the majority, could earn in accordance with their place of residence. In other words, it seems that the wage difference was not only determined by the specialisation of seniority or category that a worker achieved in a company but also by the specific business structure of each municipality. This finding will oblige future research to include the variable “space or place of residence” if we want to understand the differences in the survival of workers in local contexts a few kilometres apart from each other. In our area of study, working as a day labourer in the capital could mean earning one peseta less on average than in Getxo, and up to 2 pesetas less than a similar worker in the industrial town of Sestao (see Table 5).

On the other hand, applying a diet for all workers from new information sources and the exact prices in this same year has enabled us to conclude that the minimum wages recorded in the municipal registers of inhabitants for the most vulnerable working-class families (low or unskilled, of medium age with young dependent children) were insufficient to cover the cost of living in each municipality. This is very clear in the city of Bilbao, although it was less limiting than Getxo and there was a little leeway for the residents in Sestao (see Table 10). This could have given rise to a high level of intermunicipal mobility of the population within the metropolitan areas in search of a better quality of life and living conditions.

These two conclusions are highly relevant and raise new questions for the local historiography and other industrial areas. Our results clearly reveal the absence of integration and homogeneity between the industrial labour markets even though they were geographically close to one another. Therefore, future research that seeks to find new and consistent documentary sources could generate interesting results regarding the alternative strategies used by these families that had insufficient income even in dates as late as the 1920s. In this respect, it would be useful to implement reasonable calculations of the weight and possibilities of an increase in income that each labour market could offer to the majority of families. It is important to consider the income of all members of the family, particularly the wages contributed by the married women, guests and relatives and the labour options of the children in the formal economy, which was not incompatible with attending school (Pérez-Fuentes and Pareja, 2013). With respect to the income of the breadwinners, it is possible to advance further in the calculation of the real contribution, including daily overtime, Sunday work or working from home.

Finally, in the section on expenses, it is necessary to conduct a systematic search for precise sources to enable us to calculate the exact housing rental prices on a municipal level. It is very difficult to find this information and, once it has been found, it requires a considerable effort from the researchers. However, we believe that it is worth it due to the clearly evident impact on the working-class wages and the volatility of the local urban rental markets, which could vary substantially depending on the municipal or provincial investment in working-class housing. In short, new findings and new research challenges will help us advance our knowledge on the well-being and quality of life of the working-class population in the emerging urban areas during the first third of the twentieth century.

References

ALONSO OLEA, Eduardo J. (2001): “Santa Ana de Bolueta. Salarios y condiciones de trabajo. 1841-1941”, Vasconia, 31, pp. 135-64.

ALONSO OLEA, Eduardo J. (ed.), (2001): Información sobre la Hacienda provincial. Bilbao, Diputación Foral de Bizkaia - Instituto de Derecho Histórico de Vasconia.

ALONSO OLEA, Eduardo J.; ERRO GASCA, Carmen and ARANA PÉREZ, Ignacio (1998): Santa Ana de Bolueta 1841-1998. Renovación y supervivencia en la siderurgia vizcaína. Bilbao, Santa Ana de Bolueta.

AZPIRI ALBÍSTEGUI, Ana (2000): Urbanismo en Bilbao: 1900-1930. Vitoria, Gobierno Vasco.

BEASCOECHEA GANGOITI, José María (2002): “La ciudad segregada de principios del siglo XX. Neguri, un suburbio burgués de Bilbao”, Historia contemporánea, 24, pp. 245-280. https://ojs.ehu.eus/index.php/HC/article/view/5972.

BEASCOECHEA GANGOITI, José María (2007): Propiedad, burguesía y territorio. La conformación urbana de Getxo en la Ría de Bilbao, 1850-1900. Bilbao, Servicio Editorial de la Universidad del País Vasco-EHU.

BEASCOECHEA GANGOITI, José María (2015): “Espacios sociales y mercado laboral cualificado en Bilbao, 1900-1930”. In Jose Mª Beascoechea Gangoiti and Luis E. Otero Carvajal (eds.), Las nuevas clases medias urbanas. Transformación y cambio social en España, 1900-1936. Madrid, La Catarata, pp. 142-69.

BEASCOECHEA GANGOITI, José María (2024): “Centro y periferia, desigualdad social y urbana en Bilbao (1890-1936)”. In Manuel Montero and Susana Serrano (eds.), Bilbao. Desarrollo urbano y desigualdad en una ciudad industrial (1876-1936). Madrid, Sílex, pp. 95-151.

BEASCOECHEA GANGOITI, José María and SERRANO ABAD, Susana (2024): “Elecciones y poder local en Bilbao entre 1917 y 1936: Una perspectiva urbana y social”, Studia Historica. Historia Contemporánea, 42, pp. 39-66. https://doi.org/10.14201/shhc2024423966.

BEASCOECHEA GANGOITI, José María and ZARRAGA SANGRONIZ, Karmele (2011): “Sociedad y espacio urbano en Getxo durante la década de 1920”. In A. Pareja Alonso (ed.), El capital humano en el mundo urbano. Experiencias desde los padrones municipales (1850-1930). Bilbao, Servicio Editorial de la Universidad del País Vasco-EHU, pp. 145-66.

BEASCOECHEA GANGOITI, José María; SERRANO ABAD, Susana, and PAREJA ALONSO, Arantza (2017): “New Actors in a Modern Services Sector. The City of Bilbao (1900-1930)”, History of Retailing and Consumption, 3(2), pp. 102-19.

BORDERÍAS MONDÉJAR, Cristina (2006): “El trabajo de las mujeres. Discursos y prácticas”. In Isabel Morant (dir.), Historia de las mujeres en España y América Latina. (Del siglo XIX a los umbrales del XX, Vol. 3, pp. 353-379.