AREAS Revista Internacional de Ciencias Sociales, 47/2024 “Family Budgets and Living Standards in Spain in the 1920s”, pp. 15-44. DOI: https://doi.org/10.6018/areas.624441

Family Budgets and Living Standards in 1924 Catalonia (Spain)

Cristina Borderías, Universitat de Barcelona

Lisard Palau, Universitat de Barcelona

Joana Maria Pujadas-Mora, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya – Centre d’Estudis Demogràfics

Abstract

This article reconstructs household budgets during the first phase of the family life cycle in 24 municipalities representing different economic development models and in twelve industrial colonies in the provinces of Barcelona and Girona in 1924. Based on wage declarations recorded in the municipal registers of that year and the reconstruction of a “respectability” basket of goods, the article aims to determine the purchasing power of various social strata. For this purpose, the HISCO and HISCLASS occupational and social classification systems were used, alongside an analysis grounded in descriptive and multivariable statistics.

Key words: Household budgets, living standards, nuclear and stem families, municipal population registers, Catalonia.

Presupuestos familiares y niveles de vida en Cataluña (España) en 1924

Resumen

Este artículo reconstruye los presupuestos de los hogares en la primera fase del ciclo de vida familiar en 24 municipios representativos de distintos modelos de desarrollo económico y en doce colonias industriales de las provincias de Barcelona y Girona, en 1924. A partir de las declaraciones salariales registradas en los padrones municipales de ese año, y de la reconstrucción de una cesta de la compra de respetabilidad, el objetivo del artículo es determinar la capacidad adquisitiva de los diversos estratos sociales. Para ello se ha utilizado la clasificación ocupacional y social HISCO e HISCLASS y un análisis basado en estadística descriptica y multivariable.

Palabras clave: Presupuestos familiares, niveles de vida, familias nucleares y troncales, padrones de población, Cataluña.

Date of receipt of the original: July 26, 2024: final version: eptember 13, 2024.

- Cristina Borderías, Universitat de Barcelona. E-mail: cborderiasm@ub.edu; ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9351-3432.

- Lisard Palau, Universitat de Barcelona. E-mail: lisard.palau@ub.edu; ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5305-6380.

- Joana Maria Pujadas-Mora, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya – Centre d’Estudis Demogràfics. E-mail: jpujadasmo@uoc.edu; ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4975-639X

Family Budgets and Living Standards in 1924 Catalonia (Spain)1

Cristina Borderías, Universitat de Barcelona

Lisard Palau, Universitat de Barcelona

Joana Maria Pujadas-Mora, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya – Centre d’Estudis Demogràfics

1. Introduction

The literature on living standards has traditionally taken male wages as the main indicator, and has considered female wages to be marginal, as we suggested in the introduction to this special issue. Although some of the surveys carried out in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries took into account the contributions of other family members, most of the (few) standard family budgets that were calculated on the basis of these surveys excluded the contribution of women, a practice that affected the ways in which historians have used the data they provided2. With regard to the assessments of family consumption, most were very simple summaries of expenditure on food, housing, clothing and other items, which failed to specify the components of these items or to analyse the nutrients in the diets consumed)3. For this reason, studies on living standards in Catalonia have been based primarily on real wages (Maluquer, 2005) and, in recent decades, on biological life indicators (Ramón-Muñoz et. al. 2016, 2021; Cussó-Segura, 2005), with the exception of the studies based on family budgets (Borderías et. al 2001; Borderías et al. 2018; Borderías et al. 2023).

In Catalonia, regardless of the sources and methodologies used, studies on living standards have coincided in highlighting the decline in real wages in the second half of the nineteenth century, the result not only of the deterioration of nominal wages but also of the repeated price rises. In medium-sized textile towns, neither at the end of the nineteenth century nor in the first decades of the twentieth could the families of textile workers subsist on the wage of the head of the family (Deu, 1987; Camps, 1991, 2004; Llonch, 2007; Borderías et al. 2018). This shortfall was reflected in the study of workers’ economies published in 1892 by Juan Sallarés y Pla, a politician and leading textile businessman who was president of the Sabadell manufacturers‘ guild and of the large Catalan employers’ association Fomento del Trabajo Nacional, and who defended the need for female and child labour in Catalan textile factories. Very similar results have been found for rural families (Colomer et al. 2002; Garrabou et al. 2015).

The evidence available for the city of Barcelona has shown that, in the mid-nineteenth century, working-class families did not live according to the breadwinner-housewife model, even though this may have been the aspiration of some working-class sectors. Indeed, in 1856 married women made up half of the working population of Barcelona (Borderíaset al. 2001, 2003). Low male wages made it essential for wives to enter the labour market, and also their children, at an early age (Borderías 2013a, 2013b). The recessions that affected the Catalan textile industry in the last two decades of the nineteenth century, including the city of Barcelona, would prolong this situation, with wage stagnation and continuous price increases at least until the 1890s.

The evolution that took place between the 1890s and the beginning of the First World War is still the subject of historiographical debate, polarized between, on the one hand, historians who emphasize a deterioration caused by the decline in nominal wages and the rise in prices (Balcells, 1974; Enrech, 2005; Borderías, 2021; Borderías et al. 2023), with negative repercussions on health (Cussó, 2005) and, on the other, those who argue for a greater stability (Maluquer, 2005). The workers’ mobilizations during the period that Spanish historians refer to as the Bolshevik triennium gradually succeeded in bringing wages closer to the cost of living, but the prolongation of inflation until 1920 counteracted the wage increases for a few more years, without the family wage becoming widespread4.

At present we know little about standards of living in the 1920s. Given the absence of any detailed family budgets, the municipal population registers in Catalonia in 1924 are the only sources of information on family structure, economic activity, and wages before the Civil War, and the only ones from which we can extract significant evidence on that decade. Unfortunately, we do not have the register for the year 1924 for the city of Barcelona, and so its study requires the use of other sources (Borderías et al. 2023).

The insights provided by the results of an initial study of the working-class economies of Catalonia based on the municipal population registers (Borderías et al., 2018) convinced us of the need to broaden the scope of the study in the article we are presenting here. In this new study, first we triple the number of municipalities analysed, and second we include the most important textile company towns in Catalonia. We thus cover a larger socio-geographical area with more diversified economic development models, a focus that should allow us to better capture regional and occupational differences. Third, in our analysis we include all the individuals registered, and thus all occupations, not just day-labourers, in order to test the relatively widespread hypothesis that while the wages of unskilled workers had not yet reached the level of the family wage in the 1920s, skilled workers (considered the labour aristocracy), artisans, and the middle classes, were able to live according to the breadwinner-housewife model in this period. Fourth, we analyse both the subsistence capacity of families in which only the head of the household declared a wage, and that of families with a double income (i.e., with both spouses earning), concentrating in both cases on the first, most precarious phase of the family life course, that is, before the children reach working age. Fifth, we analyse the balance of income and expenditure in households made up of a widowed adult with young children, or in households made up of single women. Finally, we use the standard occupational classification systems Historical International Standard of Classification of Occupations (HISCO) and Historical International Social Class Scheme (HISCLASS) in order to be able to compare our data with those from other regions.

After this introduction, the article is divided into six sections. The second describes the sources and the methodology used; the third analyses the purchasing power of male wages, focusing on sole breadwinners, a minority figure in the Catalonia of 1924. The fourth discusses female wages and their contribution con to the household economy, and the fifth explores the living standards of families in which both spouses are in employment. The sixth section examines the economies of families in which one of the spouses is widowed before the children become economically active, or in the case of single women supporting themselves on their wages alone. We close, as usual, with the conclusions.

2. Sources and methodology

The main source used for this study, and the rest of this special issue, is the set of municipal population registers for 1924: specifically, the registers from 24 municipalities and 12 company towns located in the provinces of Barcelona and Girona are used5. Unusually in the case of Catalonia, all these registers contain information on wages. As is to be expected, the data were recorded regularly in the case of men but only in exceptional instances in the case of women.

The data analysed correspond to 88,068 individuals, of whom 61,809 were aged between 14 and 64 years old and 39,140 reported being economically active (table 1). Seventeen per cent were male day-labourers, 4% female day-labourers and 2% said they were in employment, but without specifying the occupation (describing themselves as workers or labourers or using other similar terms). As usual, and with the exception of those living in company towns, women’s employment was widely underreported, and no alternative sources such as worker censuses or factory or company sources that might enable us to reconstruct their activity are available.

Table 6 displays the reconstructed activity for seven of these municipalities, and highlights the significant extent of underreporting (Borderías, 2013b). In some previous research it has been assumed that the wives of farmers and agricultural labourers could be classified as equivalent to their husbands, but the situation in Catalonia is rather more complex, as many wives of agricultural labourers worked in textile factories.

Table 1. Population analysed by type of economic activity (1924).6

|

Type of economy |

Men in primary sector |

Women in primary sector |

Men in secondary sector |

Women in secondary sector |

Women in tertiary sector |

Male day labourer |

Female day labourer |

Unclassified |

Total active population |

Population aged 14-64 |

Sample population |

Total population 1920 (national census) |

|

|

55% |

0% |

19% |

5% |

9% |

3% |

9% |

0% |

1% |

3676 |

6451 |

9440 |

9505 |

|

|

Textile industry |

13% |

0% |

28% |

25% |

10% |

3% |

13% |

5% |

2% |

16255 |

22016 |

31095 |

31610 |

|

Other industries |

25% |

0% |

35% |

10% |

13% |

4% |

10% |

1% |

3% |

7415 |

12618 |

17597 |

16652 |

|

Mixed economies |

25% |

0% |

35% |

10% |

13% |

4% |

10% |

1% |

3% |

10581 |

19168 |

27752 |

62213 |

|

2% |

0% |

20% |

32% |

4% |

2% |

28% |

10% |

3% |

1213 |

1556 |

2181 |

- |

Source: Own elaboration based on the PADROCAT and BALL databases.

Note: Primary sector: Municipalities where the primary sector is the dominant economic activity. Textile Industry: Municipalities where the textile industry accounts for more than 50% of the economic activity. Other Industries: Municipalities where the secondary sector represents more than 50% of the economic activity, excluding those where the textile industry is the leading sector. Mixed economies: Municipalities where the tertiary sector constitutes more than 25% of the economic activity.

The 24 municipalities studied cover a wide variety of economic development models (appendix 1). In some municipalities male agricultural workers accounted for far more than half the population, sometimes even reaching the figure of 90%; in others, such as Llagostera and Sant Vicenç dels Horts, more than two thirds of workers were employed in the primary or industrial sectors. In other municipalities employment was based on textile production, with a high proportion of female workers; others still were not textile-based but specialized in wood, metal or cork, which they combined with agriculture or services. This multiple economic activity was one of the characteristics of most towns. Finally, the study also includes twelve textile company towns, with a high proportion (indeed, a majority) of women working in their factories.

One of our main objects of study is the nuclear family during the first phase of the life course, that is, before the children become economically active. To define the ages of the head of the family for our analysis we use the average age at the time of marriage, calculated using the SMAM (Singulate Mean Age at Marriage). The SMAM in the province of Barcelona in 1920 was 28.24 years and in 1930, 27.66 years (Cachinero Sánchez, ١٩٨٢). These figures are similar to the ones published by Cabré and Torrents (1991) for the generations born in Catalonia between 1891 and 1910, which ranged from 27.99 years for the 1891-95 cohort to 28.80 years for the 1906-10 cohort. This late marriage age was accompanied by a decline in fertility; in fact, the fall in marital fertility in Spain had begun in Catalonia in the first half of the nineteenth century. These figures explain why in 1920 women in Catalonia born between 1886 and 1895 only had a cumulative offspring of 2.07 children, and those born after 1895 had 1.01 children (Cabré, 1989; Gil Alonso, 2022). In this context, in the case of our sample of populations and using the perspective of the “breadwinner”, 80% of married men and heads of household aged between 26 and 45 reported having only one or two children. Specifically, half of men aged 26 to 35 had only one child, and 40% of those aged 36 to 45. The former figure is relatively high, suggesting that many of these couples might choose not to have a second child. However, the same proportion of men in both age groups (35%) reported having only two children. As a result, in view of the data on general fertility and those recorded in our data set, we decided to focus part of our analysis on families with two inactive younger children (i.e., type 3b families in Laslett’s classification).

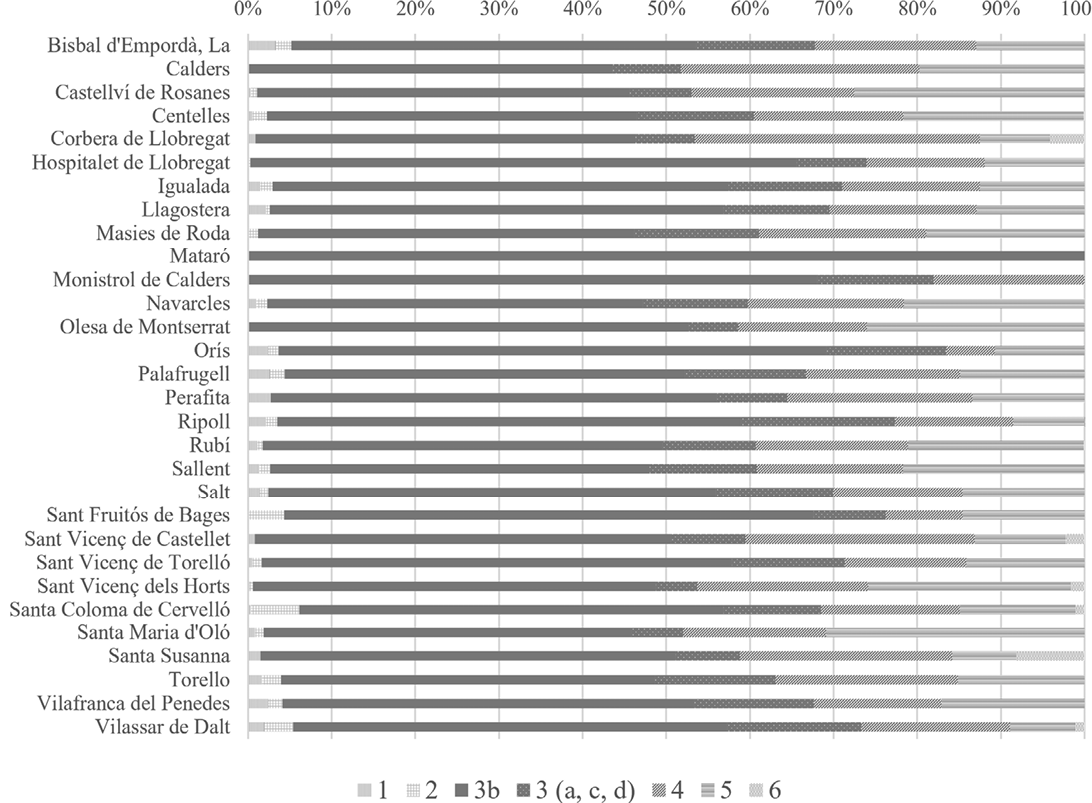

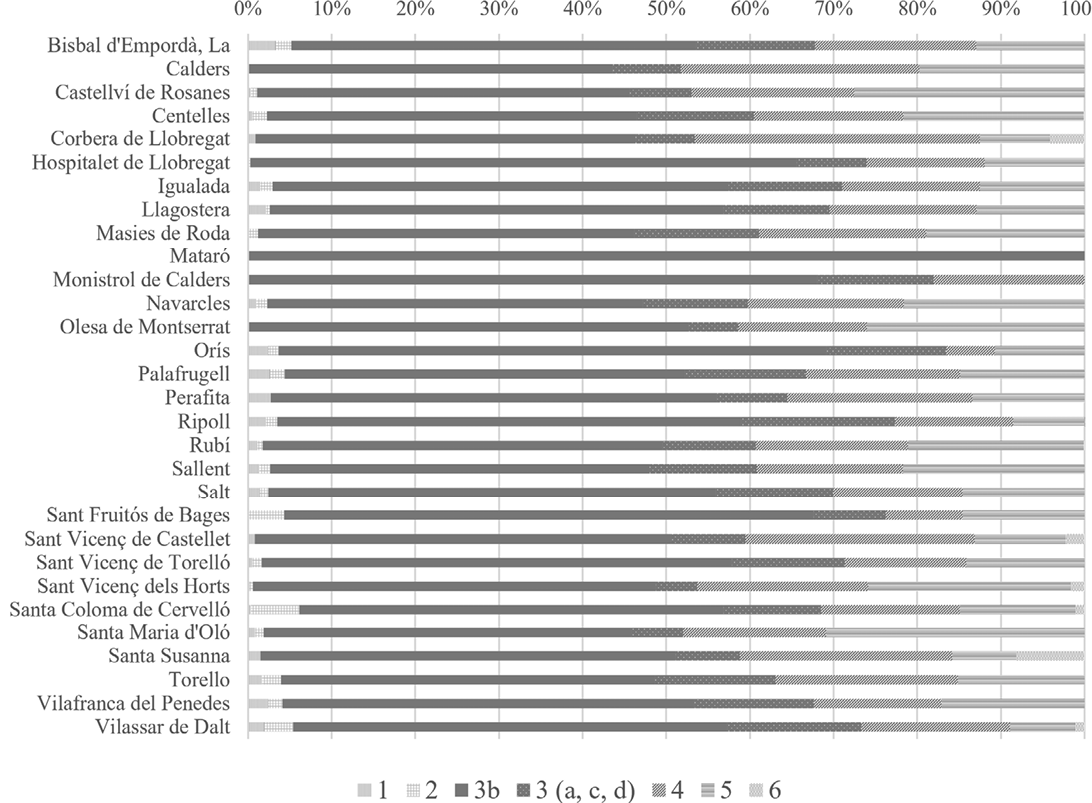

In parallel with the demographic change, there was a notable evolution of the family structure towards a conjugal model, which established the nuclear family as the most common model in Catalonia and Spain throughout the twentieth century. In our sample, we observed that the nuclear family (Laslett’s classification 3) represents more than 70% of the total number of families in almost all the textile company towns and in municipalities with a mixed economy such as Hospitalet de Llobregat (figure 1). In the textile municipalities, the nuclear family is the most frequent type, although its predominance varies significantly, ranging from barely 58% in Centelles to 67% in Salt. These figures indicate a progression towards the imposition of the nuclear family model, which will be observed more generally in Spain decades later (del Campo and Rodríguez-Brioso, 2002); alternatively, it might be attributed to the type of housing offered in the company towns (Palau, 2024). At the same time, in nuclear households, the predominant type is 3b, which corresponds to married couples with children. Many of these would be in the early stages of family life, with children who are not yet economically active (Figure 1). In almost all the textile company towns analysed and in municipalities with textile industries such as Salt, Vilassar de Dalt and Torelló, more than 88% of the nuclear families are type 3b.

However, in the towns where the primary sector predominated the proportion of nuclear families does not exceed 61%, the figure recorded in Perafita, while in Santa Susanna it barely reaches 57% (figure 1: the sole exception is Llagostera). This phenomenon is attributed, in part, to the notable presence of complex family arrangements, such as stem or joint families. Among the eight municipalities with a greater presence of stem families, that is, where their proportion exceeds 20%, in four of them – Corbera de Llobregat, Santa Susanna, Perafita and Sant Vicenç dels Horts – agriculture is the main economic activity. In this context, this type of family structure makes sense from an economic perspective.

Moreover, high rates of stem families are also observed in the company towns of Calders and Masies de Roda, as well as in municipalities with industrial activity such as Sant Vicenç de Castellet and Torelló. These data suggest the persistence of these family forms in the first decades of the twentieth century (Borderías and Ferrer-Alòs, 2017), which might indicate that the stem family was viable not only economically, but also from a social and cultural perspective. However, an assessment of this issue is beyond the scope of the present study.

Figure 1. Family/household type according to Laslett’s classification, Catalonia, 1924. Ordered by the weight of family type 3b, from lowest to highest.

Source: Based on data extracted from the PADROCAT and BALL databases.

Note: Mataró is not included as all the families are type 3b.

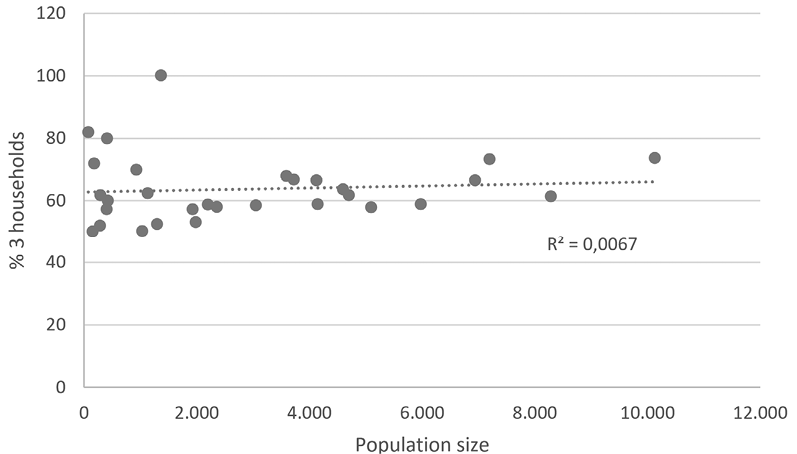

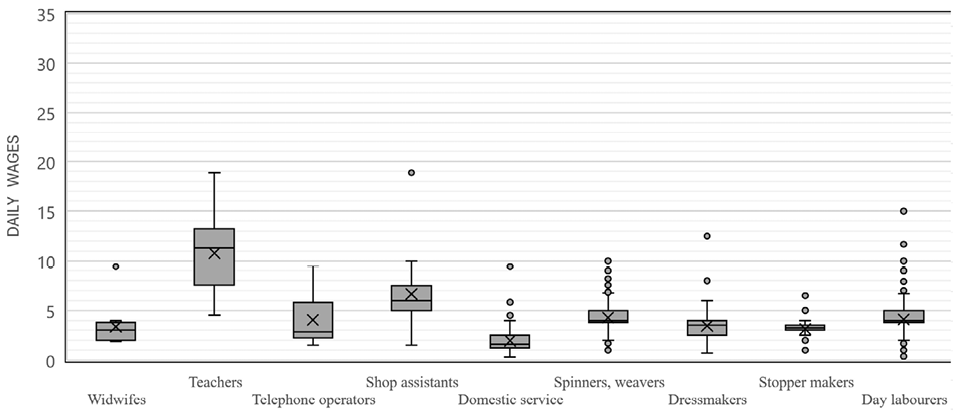

As well, no significant association is found between the percentage of nuclear families and the size of the municipality (figure 2). This lack of correlation is also observed in the case of stem families (appendix 2). As regards declared wages, both for men and women, their reliability has been verified by consulting the Estadística de Salarios y Jornadas de Trabajo (Statistics on Wages and Working Days) published by the Ministry of Labour (1914-1930), local sources, and various publications (Deu, 1987; Gabriel, 1988; Soler, 1997; Enrech, 2004, 2005; Llonch, 2004; Borderías, 2004, 2013a; Vilar, 2014).

Family income is calculated on the basis of 265 working days per year7. Previous studies (including Enrech, 2005) have estimated that workers worked 300 days, but our research suggests that this is a theoretical figure rather than a real one, deriving from discounting only religious and local holidays (García Zúñiga 2014) without taking into account days not worked due for example to illness, accidents, or technical stoppages. The local sources available, and especially the figures for family budgets for 1917 and 1919 recorded by the statistical office of the Barcelona City Council, support our estimates. A recent study on company towns reported that, although textile factories were open between 285 and 295 days a year, the number of annual days actually worked by their employees ranged between 260 and 270 (Palau, 2024).

Figure 2: Percentage of nuclear families (type 3) versus population size, Catalonia, 1924.

Source: Based on data extracted from the PADROCAT and BALL databases.

For the family budgets, we use Cristina Borderías’s budget for working-class families in Catalonia (published in Borderías et al., 2018) (table 2). The reconstruction of the food diet takes into account the criteria published by the FAO (2004) on the required nutrients (calories, proteins, vitamins and micronutrients) for adults, considering the different needs of men and women (and children) and the specific physical conditions of the Spanish population in 19248. This optimal diet is composed of standard local products and comprises the nutrients necessary to ensure the healthy reproduction of men, women and children. This diet is equivalent to Allen’s respectability basket, which is currently used in most studies on living standards (Allen, 2015; Horrell et al., 2021, 2022; Boter, 2020).

Table 2. Cost of living, 1924 (pesetas per day)

|

Cost of living |

Average cost |

% of total cost |

|

Food |

6.37 |

74.70 |

|

Housing + lighting |

0.75 |

8.80 |

|

Other expenses |

1.41 |

16.50 |

|

Total |

8.53 |

100.0 |

Source: Data for Catalonia published in Borderías et al. 2018: p. 95.

In addition to food, which accounted for almost 75% of the total budget, we also include spending on housing (rent and maintenance), lighting and fuel. Social costs (for example, money spent on schooling and medical and pharmaceutical care), though minimal, are also mentioned in most workers’ budgets of that decade. The expenditure is calculated using the average provincial prices published in the Boletín del Instituto de Reformas Sociales (Bulletin of the Institute of Social Reforms), after comparison with some local prices.

In order to define the purchasing power of the family wage we calculate the wages of male heads of household in families comprising a married couple and two inactive young children (type 3b in Laslett’s classification). To cover the cost of the shopping basket, which amounted to 8.53 pesetas per day (table 2), and working 265 days per year, a daily wage of at least 11.74 pesetas is required.

With the family as the unit of analysis, it is necessary to calculate as accurately as possible the whole of the family’s monetary and non-monetary income. However, for this article we have not been able to gather data on food production for personal consumption, rent transfer, credits, loans, charity or other resources. Our research is limited to the wages recorded in the 1924 municipal registers and to an analysis of the capacity of these wages to attain family subsistence9. We are also able to analyse the economies of dual-income households, even though these are fewer in number (see tables 7 and 8). We calculate the capacity of widows’ and widowers’ wages to support their households with inactive children under 12 (Laslett families 3c and 3d). And finally, we assess the capacity of households comprising only single women to support themselves with their wage alone. In all cases, the shopping basket is adjusted to the composition of these types of household and to their consumption (table 11).

Finally, in order to complement the results obtained through descriptive statistics, and in order to identify the socioeconomic and demographic factors associated with the family wage, we carry out two logistic regression models. In both cases, the dependent variable is whether or not the husband received a wage of 11.74 pesetas or more; while in the first model the independent variables comprise the husband’s social/occupational group, the municipality of residence, the husband’s age and the number of children, in the second model the wife’s wage range is added. Logistic regression is especially useful in this context, since it allows a dichotomous dependent variable (i.e., reaching or not reaching a certain level of income) to be modelled based on multiple independent variables. This approach helps to identify the factors that influence the variability of the observed results and also permits an estimation of the direction and magnitude of these relationships, while simultaneously controlling for the effect of the set of variables. In this way, the models proposed allow the identification of the specific impact of each factor. For more details on the methodological specifications, see appendix 4.

3. The purchasing power of men’s wages: the myth of the breadwinner

In an earlier study of the economic capacity of workers in Catalonia in 1924, we showed that only 5% of agricultural and industrial day-labourers earned a wage capable of covering the family budget10. The new evidence gathered in the present article paints an even bleaker picture11. Firstly, the increase in the number of cases analysed described above in section 2 brings down the rate of households able to make ends meet to 3.27%12; this is because of the inclusion of company towns and rural municipalities with wages below the average level in Catalonia as a whole. Secondly, it is also pessimistic because it shows that not only day-labourers received deficient wages. The literature on living standards has focused mainly on agricultural and industrial day-labourers and some construction trades such as bricklayers, under the assumption that skilled workers, the so-called labour aristocracy, and white-collar workers and professionals, already earned the family wage. Our inclusion of all the workers registered in the municipal records, with their respective trades and professions, shows that this hypothesis is not borne out in the Catalan population. Below, we present the evidence that supports this assertion.

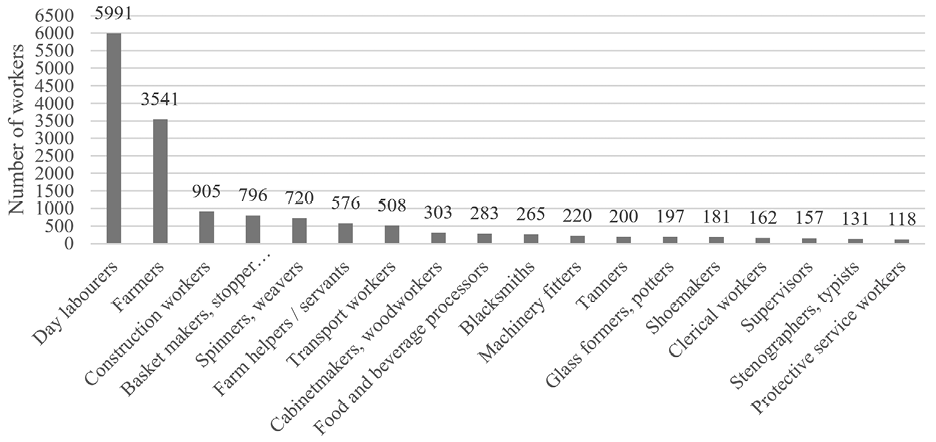

As the nineteenth century progressed, the descriptions of trades became less specific. The term “day-labourer” tends to be used, which means that we cannot identify the sectors in which workers were employed. This lack of definition also affected other headings such as “sales personnel”, which does not specify whether a particular person was, for example, a shop assistant or a small shopkeeper. The same applies to artisan trades such as shoemaker or bricklayer: we do not know whether an individual is a master craftsman, a journeyman, an apprentice, a workshop owner or a simple worker. These problems are less grave when the individuals analysed report their wage and type of wage (annual, weekly or daily), information that can shed light on their occupational category. Taking these reservations into account, the data provided on employment in the 24 municipalities are presented in Figure 3. Thus, the most frequent occupation reported among men was day-labourer (40%), followed by farmer (23%). Interestingly, while only 4% of men were textile workers, as many as 32% of women who reported an occupation were employed in the textile industry. To analyse their wages and their purchasing power, we use the international codes HISCO and HISCLASS.

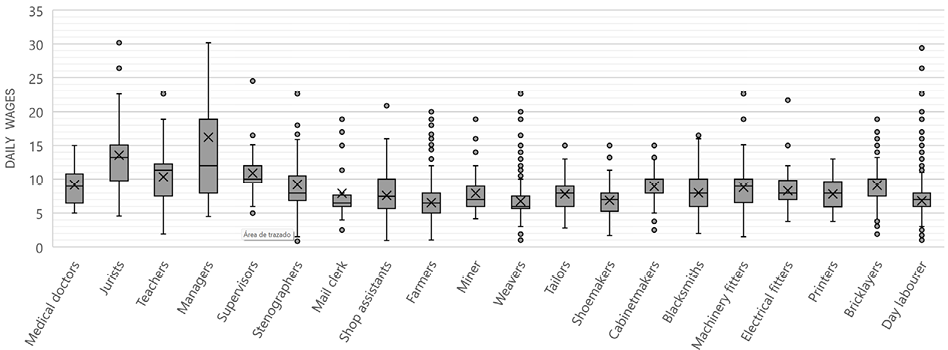

The average wage of male workers was seven pesetas per day. This figure is based on the population of agricultural and industrial day-labourers and that of textile workers, who accounted for 64% of those in employment13. Figure 4 shows that the rest of the main occupations had somewhat higher average wages. In any case, the wage range is relatively narrow, except in the case of factory managers and to a lesser extent of independent professionals such as lawyers, doctors, and teachers.

Figure 3: Occupational structure of male adult workers. Catalonia, 1924

Source: Based on data extracted from the PADROCAT and BALL databases.

Note: The figure includes only occupations with more than 100 workers. The sample represented comprises 15,254 male workers out of a total of 16,826 aged over 25 who reported their wages (91%). The occupational structure of these workers is based on the HISCO minor groups.

Figure 4. Wage range and dispersion of main male occupations

Source: Based on data extracted from the PADROCAT and BALL databases.

Note: The occupations shown in this graph reflect the diversity of male occupations. The sample represents 13,473 male workers out of a total of 16,826 aged over 25 who reported earnings (80%). The names of the occupations are based on the HISCO minor groups.

Table 3 shows this in greater detail. HISCO groups 5 to 9 (service workers (5), agricultural, animal husbandry and forestry workers and fishermen and hunters (6) and agricultural and industrial day-labourers (7, 8 and 9) have standard deviations below 4. As expected, the standard deviation of groups 1 to 4 (professional and technical workers (1), administrative and managerial workers (2), clerical workers (3) and sales workers) was higher – between 4.58 and 5.8 – given that their average wage was 9.9 pesetas, almost three pesetas more than the general average of 7 pesetas per day.

Table 3. Male and female wages according to HISCO groups

|

HISCO major groups |

Men |

Women |

||

|

Average wage |

Standard deviation |

Average wage |

Standard deviation |

|

|

Professional, technical and related workers (0) |

12.8 |

6 |

4.3 |

2.4 |

|

Professional, technical and related workers (1) |

8.5 |

4.8 |

10.1 |

2.7 |

|

Administrative and managerial workers (2) |

11.8 |

5.8 |

6.9 |

3.1 |

|

Clerical and related workers (3) |

9.6 |

5.8 |

4.7 |

2.8 |

|

Sales workers (4) |

9 |

4.8 |

6.4 |

3.3 |

|

Service workers (5) |

7.3 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

|

Agricultural, animal husbandry and forestry workers (6) |

6.7 |

1.8 |

4.5 |

2.3 |

|

Production and related workers and labourers (7) |

7.5 |

2.6 |

4.3 |

0.9 |

|

Production and related workers and labourers (8) |

8.2 |

2.5 |

5.9 |

3.4 |

|

Production and related workers and labourers (9) |

7.2 |

2 |

4.2 |

1 |

|

Total |

7.4 |

2.7 |

4.3 |

1.2 |

Source: Based on data extracted from the PADROCAT and BALL databases.

Note: Wages of workers between the ages of 25 and 46.

It is worth mentioning that the differences in wage between municipalities are also very small, especially in working class groups and among service workers, whose standard deviation is around 2 (see appendix 3).

We said above that the deficient wages were not exclusive to day-labourers and unskilled workers. Interestingly, in four of the 24 municipalities analysed and in seven of the twelve company towns none of the heads of household were able to support their wives and children, meaning that in these sites wages were insufficient in all occupations14. These data reflect the depreciation of textile wages during the second industrial revolution. In addition, the wages of skilled workers, white-collar professionals, liberal professionals and sales personnel were insufficient to cover the family budget.

Table 4 below summarizes the purchasing power of all occupations using the HISCLASS classification. As can be seen, on average adult workers were able to cover 63.1% of the family budget, a rate similar to those recorded in France and the Netherlands and lower than in Great Britain in the mid-nineteenth century (Burnette 2024:13). Below this rate were the skilled and unskilled agricultural workers (groups 4 and 7) with percentages around 50%, very similar to those of the agricultural labourers in the Netherlands (42%) at the beginning of the twentieth century (Boter, 2020).

Table 4. Coverage of the household budget for male adult workers aged 26 to 45 according to their skill level (%)

|

HISCLASS groups |

<60 |

60-79.99 |

80-99.99 |

>100 |

Total |

Median |

||||

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

|

Higher managers and professionals (1) |

10 |

11.0 |

13 |

14.3 |

24 |

26.3 |

44 |

48.4 |

91 |

115.8 |

|

Lower managers and professionals, clerical and sales personnel (2) |

227 |

31.5 |

192 |

26.7 |

152 |

21.1 |

149 |

20.7 |

720 |

79.1 |

|

Foremen and skilled workers (3) |

432 |

29.1 |

435 |

29.3 |

458 |

30.8 |

161 |

10.8 |

1,486 |

72.4 |

|

Farmers and fishermen (4) |

821 |

49.6 |

779 |

47.0 |

21 |

1.3 |

35 |

2.1 |

1,656 |

58.1 |

|

Lower-skilled workers (5) |

602 |

40.4 |

608 |

40.8 |

222 |

14.9 |

57 |

3.8 |

1,489 |

64.8 |

|

Unskilled workers (6) |

1,927 |

45.2 |

2,146 |

50.4 |

156 |

3.7 |

30 |

0.7 |

4,259 |

58.2 |

|

Lower-skilled and unskilled farmworkers (7) |

200 |

67.6 |

83 |

28.0 |

12 |

4.1 |

1 |

0.3 |

296 |

51.0 |

|

Total |

4,219 |

42.2 |

4,256 |

42.6 |

1,045 |

10.5 |

477 |

4.8 |

9,997 |

63.1 |

Source: Based on data extracted from the PADROCAT and BALL databases.

Note: Wages of workers between the ages of 25 and 46.

Perhaps contrary to expectations, less than half of the highest skilled group (group 1, Higher managers and professionals) earned the family wage, the income necessary to cover the family’s expenses. Lower managers and professionals (group 2) fared even worse, as less than a quarter were able to do so. More significantly, around a third of those in this last group, and of those in the foremen and skilled workers group (group 3), covered less than 60% of the family budget. Furthermore, in this last group, which might be considered the paradigm of the labour aristocracy, only 11% corresponded to the male breadwinner model.

The data for these three groups confirm that the inability to reach the household budget was not exclusive to unskilled workers. In the light of the empirical evidence presented here, the idea that among the labour aristocracy and the professional classes the figure of the breadwinner had not only taken root ideologically, but that the families of these socio-occupational groups lived according to this model, needs to be revised. Of course, if in these groups the breadwinner model was a minority, among the unskilled it was the exception, and more than half of the male workers barely reached 60% of the family budget. Table 5 displays the socio-occupational composition of male breadwinners (table 5).

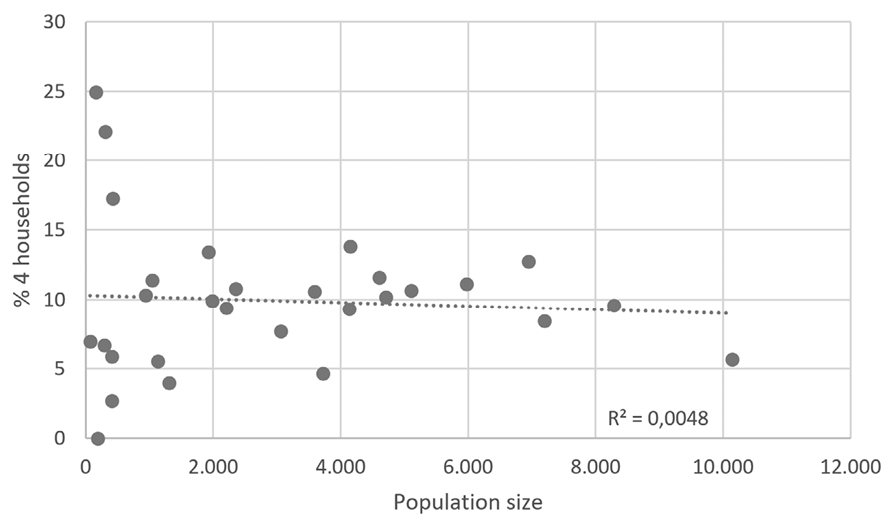

Although the active population of groups 1 and 2 accounted for 8.1% of the total number of employed, they represented 40.5% of the breadwinners. These figures reflect the inequality in the distribution of wealth, as can be clearly seen in the figure below using the Theil index, which measures inequality. This measure allows us to break down the contribution (negative or positive) of each social group to the total income according to its demographic weight (figure 5). Thus, groups 1 and 2 accumulate a large part of the wealth, while unskilled workers (group 6) do not.

Table 5. Socio-occupational composition of the breadwinners

|

HISCLASS groups |

% Breadwinners |

|

Higher managers and professionals (1) |

9.2 |

|

Lower managers and professionals, clerical and sales personnel (2) |

31.2 |

|

Foremen and skilled workers (3) |

33.8 |

|

Farmers and fishermen (4) |

7.3 |

|

Lower-skilled workers (5) |

11,9 |

|

Unskilled workers (6) |

6.3 |

|

Lower-skilled and unskilled farmworkers (7) |

0.2 |

|

All groups |

9,997 = 100 |

Source: Based on data extracted from the PADROCAT and BALL databases.

Note: Wages of workers between the ages of 25 and 46.

Comparing these data with those from other European countries is not easy, since the abundant European literature on household budgets and the population’s living standards has focused on modern times or on processes of industrialization. However, some references to the literature may be useful. The main research in Britain, for instance, has argued that industrialization made women increasingly dependent on men’s wages, not only because of wage differences but also because of the fall in employment opportunities for women and the low number of hours they worked per year (Horrell et al., 2021, 2022; Burnette, 2024). During this period, the average contribution of heads of households was 76% (Humphries, 1995); factory workers contributed 66% and agricultural labourers 85% of the family budget (Horrell et al. 1992, 1995). At the beginning of the twentieth century, heads of household employed in the cotton and linen industries in Ghent in Belgium contributed 61% and 59% respectively of the household budget, metal workers 70% and craftsmen 77% (Van den Eeckhout, 1993). Agricultural workers in the Netherlands at the beginning of the twentieth century contributed around 42% (Boter 2020). The data we have for Catalonia in the nineteenth century correspond to the city of Barcelona, in 1856, and show a lower dependence on male wages, as unskilled male workers did not cover more than 50% of the family budget.

Figure 5. Theil index by occupational groups according to skill levels

Source: Based on data extracted from the PADROCAT and BALL databases.

In any case, the data presented in table 4 show that in 1924 Catalan families15 had more need of other resources than British and Dutch workers in the nineteenth century16. In the next section we analyse the extent to which the wages of wives could cover the deficits in those of their husbands.

4. The contribution of women to family economies

In four previous studies on household budgets in Catalonia we have hypothesized that female wages made a greater contribution to the family economy than in other countries. In Barcelona in 1856, women’s wages contributed up to 30% of a family’s budget during the period in which the children were not yet economically active and no other family members were available to work (Borderías et al., 2001, 2003). This rate is very similar to the one that emerges from the analysis of official data published in the Bulletins of the National Institute of Statistics for the first decades of the twentieth century (Borderías et al., 2022). In the abovementioned pilot study of the municipal registers of nine Catalan textile municipalities in 1924, wives contributed between 30 and 40% of the family budget (Borderías et al. 2018). In the following pages our aim is to test this hypothesis in a broader and more diversified socioeconomic environment.

4.1. Female employment and wages

As we know, data on female employment and wages are not routinely included in municipal population records. Table 6 displays the rates of female activity in 13 of the municipalities analysed in this article (Borderías, 2012, 2013b)17.

In the 24 municipalities and twelve company towns that make up our dataset, we have a total of 8,946 records of female employment and 6,969 records of their wages (that is, we have data on wages in 78% of the cases).

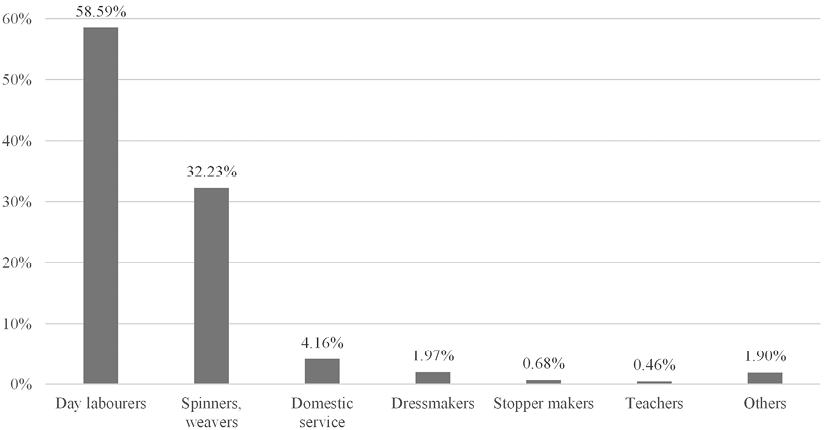

In spite of the scarcity of the data on women’s wages, we think that the results are significant and representative, given the low wage dispersion within and between occupations and between the different municipalities. Figure 6 displays the occupational structure of women; it confirms that most were day-labourers, mainly in the textile sector.

Table 6. Female activity rates by marital status and municipality

|

Municipalities |

Unmarried % |

Married % |

Widows % |

|

Hospitalet de Llobregat |

86.1 |

47.9 |

27.3 |

|

Prat de Llobregat |

59.0 |

70.8 |

14.3 |

|

Centelles |

87.4 |

55.8 |

35.0 |

|

Olesa de Montserrat |

80.7 |

60.9 |

44.4 |

|

Vilafranca del Penedés |

79.3 |

17.7 |

22.2 |

|

Rubí |

62.9 |

21.3 |

15.8 |

|

Salt |

77.9 |

32.9 |

34.1 |

|

Company town (municipalities) |

|||

|

Calders |

70.4 |

65.5 |

57.1 |

|

Masies de Roda |

94.4 |

40.8 |

35.0 |

|

Monistrol de Calders |

90.9 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Orís |

92.9 |

56.0 |

50.0 |

|

Sant Fruitós de Bages |

80.0 |

21.2 |

33.3 |

|

Sant Vicenç de Torelló |

86.9 |

13.0 |

9.7 |

Note: The data are sourced from the PADROCAT and CENOCAT databases collected by the TIG Group. Data for the first seven municipalities listed in the table were published in Borderías (2012, 2013a). These activity rates were derived by cross-referencing the municipal population registers with the 1923 workers’ censuses, ensuring high reliability in the reconstructed activity rates. However, this methodology could not be applied to the other municipalities, as the 1923 workers’ censuses are not available for these cases. The activity rates for the company towns were compiled by Palau in his doctoral thesis (2024). In this case, the reliability of the activity declarations in the 1924 municipal registers made cross-checking with the workers’ censuses unnecessary, although they were checked against company records from these company towns. As can be seen, these rates are also notably high.

Figure 6. Main occupations of women (%)

Source: Based on data extracted from the PADROCAT and BALL databases.

Note: Occupations are classified according to the HISCO system (minor groups)

Even in cities with more than 4,000 inhabitants and with a relatively developed tertiary sector, most female workers were day-labourers; manufacturing continued to be the predominant economic activity.

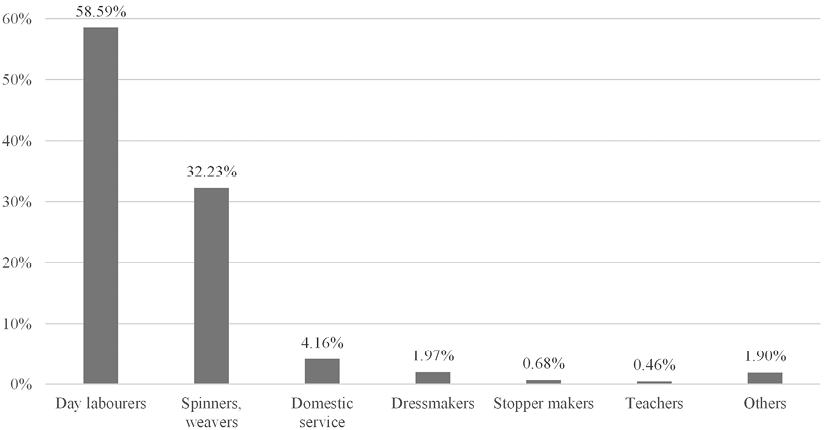

In Figure 7 we see that the average female wage was four pesetas, for both day-labourers and textile workers, the largest groups. Female workers in the cork factories of Llagostera and Palafrugell were paid less. As Table 3 shows, the wage dispersion in all three groups is minimal. Midwives, dressmakers and domestic service were paid even less, and there were no significant intra-occupational wage differences. Among shop assistants, postal workers, telephone operators and teachers, wages were higher, and the intra-occupational differences as well.

Figure 7. Wage range and dispersion of the main female occupations

Source: Based on data extracted from the PADROCAT and BALL databases.

Note: The names of the occupations correspond to the minor groups in the HISCO classification.

4.2. The contribution of wives

Most studies on the contribution of women to European family economies have focused on the pre-industrial and early industrial periods (Horrell and Humphries, 1995; Horrell et al., 2021, 2022), and so their data are not strictly comparable with ours. However, a recent article on women’s wages in Great Britain stressed the progressive dependence of women on their husbands’ income from the second decade of the nineteenth century onwards, either due to the differences in wages of men and women or due to the decrease in the employment opportunities for women compared to previous periods (Humphries et al., 2015: 430). A recent comparative analysis has supported these hypotheses (Burnette, 2024).

In Catalonia, however, female activity rates in the municipalities where we were able to obtain reliable information were high (Table 6). The contribution of wives was by no means marginal and seems to have been higher than in other cases known in Europe. In the population studied as a whole, the average contribution of wives to the family budget was 37%; among day-labourers and textile workers, who make up 83% of the sample, it ranged between 30% and 60%. But a considerable number of female workers contributed less than 30%, mainly day-labourers in cork factories (known as stopper makers)18, dressmakers, and midwives. Shop assistants, on the other hand, contributed around 50%. The majority of teachers contributed more than 60%, and 46% of them were even able to meet the household budget on their own (Table 7). This is why dual-income families, even with modest wages, could have a healthier budget than those living exclusively off a skilled worker’s wage.

Table 7. Range of daily budget covered by married women according to occupation (%)

|

|

Sample |

0-29 |

30-59 |

60-79 |

80-99 |

=/+100 |

Mean |

|

Day labourers |

1,233 |

13.8 |

83.4 |

2.5 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

36.1 |

|

Spinners, weavers |

941 |

4.3 |

94.5 |

1.3 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

36.5 |

|

Stopper makers |

20 |

55.0 |

45.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

27.2 |

|

Dressmakers |

15 |

40.0 |

60.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

30.7 |

|

Teachers |

13 |

0.0 |

15.4 |

23.1 |

15.4 |

46.2 |

99.4 |

|

Shop assistants |

6 |

0.0 |

66.7 |

16.7 |

16.7 |

0.0 |

53.9 |

|

Midwives |

6 |

33.3 |

50.0 |

0.0 |

16.7 |

0.0 |

37.3 |

|

Others |

25 |

33.3 |

40.0 |

6.7 |

20.0 |

33.3 |

43.3 |

|

Total |

2,264 |

10.6 |

86.4 |

2.2 |

0.6 |

0.3 |

36.7 |

Source: Based on data extracted from the PADROCAT and BALL databases.

Note: The names of the occupations correspond to the minor groups in the HISCO classification. Fifty-one married women who declared wages but did not register their occupation are excluded (among them, those registered as property owners or rentiers).

5. Dual-income families

The analysis of male wages highlights the gap between social discourses and the reality. In the 1920s, male breadwinners were in a minority among the Catalan working classes; nor did the labour aristocracy or professional classes live entirely according to this model. The insufficient contribution of heads of households to household economies obliged families to seek other economic resources. In the small and medium-sized municipalities under analysis here it is highly likely that food production for personal consumption was frequent, but we have no data either on this or on the possible transfers of income, loans or resources from charity19. So, for the moment, our analysis is based solely on the income of the couple. As we noted above, female wages were not often recorded, but we believe that the data we have at our disposal are sufficiently representative. In this section, we focus on the family composed of two spouses, both in employment, in the first phase of the family life course when the children are still economically inactive, in order to gain a better idea of their standard of living.

The majority of these dual-income families (83%) were able to cover more than 80% of the family budget, and a third managed to cover it completely (table 8). This underlines the importance of the wife’s wage, but it also highlights the fact that even the income of both spouses might not be sufficient, especially when the head of the household was an unskilled worker; in this scenario, complementary strategies were necessary in order to make good the deficit.

Table 8. Range of daily budget covered by the wage of the head of household and wife (%)

|

HISCLASS of the head of household |

Number of dual-income families |

<60% |

60-79,9% |

80-99,9% |

=/+100 |

|

Higher managers and professionals (1) |

2 |

0 |

50 |

0 |

50 |

|

Lower managers and professionals, clerical and sales personnel (2) |

40 |

3 |

23 |

23 |

53 |

|

Foremen and skilled workers (3) |

172 |

2 |

18 |

30 |

51 |

|

Farmers and fishermen (4) |

157 |

2 |

11 |

61 |

26 |

|

Lower-skilled workers (5) |

277 |

1 |

5 |

66 |

27 |

|

Unskilled workers (6) |

518 |

2 |

19 |

57 |

22 |

|

Lower-skilled and unskilled farmworkers (7) |

21 |

5 |

52 |

38 |

5 |

|

Total |

1,187 |

2 |

16 |

54 |

29 |

Source: Based on data extracted from the PADROCAT and BALL databases.

It is worth considering whether the savings that couples were able to make before the birth of their children might have alleviated the general deficit we have been discussing. In table 9 below we calibrate the effect of savings on the household economy. We find that for day-labourer families its effect was insignificant: the average savings did not even amount to four daily shopping baskets per year. However, the amount saved was twice that reported for English families in 1780 (Horrell et al., 2022:544).

Table 9. Households’ savings during the first two years of marriage

|

HISCLASS of the head of household |

Average daily wage - head of household |

Average daily wage - wife |

2-year household head’s wage |

2-year wife wage |

Expenditure for these 2 years |

Savings during these 2 years |

Days covered by the savings |

|

Lower managers and professionals, clerical and sales personnel (2) |

9 |

4.4 |

4757.2 |

2320 |

4981.5 |

2095.7 |

246 |

|

Foremen and skilled workers (3) |

7.3 |

4.2 |

3875.7 |

2238.3 |

4981.5 |

1132.5 |

133 |

|

Farmers and fishermen (4) |

6.4 |

4.2 |

3397 |

2243.4 |

4981.5 |

658.8 |

77 |

|

Lower-skilled workers (5) |

6.4 |

4.3 |

3382 |

2257.9 |

4981.5 |

658.4 |

77 |

|

Unskilled workers (6) |

6.5 |

4.2 |

3461.6 |

2230.2 |

4981.5 |

710.3 |

83 |

|

Lower-skilled and unskilled farmworkers (7) |

5.9 |

4.1 |

3111.3 |

2168.5 |

4981.5 |

298.3 |

35 |

|

Total |

6.7 |

4.2 |

3524.8 |

2240 |

4981.5 |

783.3 |

92 |

Source: Based on data extracted from the household budgets published in Borderías 2013b, Borderías et al.2018.

After using descriptive statistics to analyse the extent to which male and female wages were needed to support their families, and to determine the living standards of dual-income families, we now go a step further to try to identify the factors associated with the family wage. In order to measure the socioeconomic and demographic factors that are related to the family wage, two logistic regression models have been estimated. As stated above, the dependent variable in the models is a daily wage of 11.74 pesetas or more – the threshold necessary to cover the needs of a family with non-productive children. The independent variables considered are the municipality of residence, age, number of children and the wife’s wage range.

In model 1 (displayed in table 10), we see that higher managers and professionals (HISCLASS 1), lower managers and professionals, clerical and sales personnel (2), foremen and skilled workers (3) and the owners (8) are between 16 and 47 times more likely to attain the income necessary to cover the family budget than the reference group of unskilled workers (group 6), which is also the largest group. Likewise, farmers and fishermen (4) and lower-skilled workers (5) are also more prone than the reference group to obtain the necessary resources, though in the case the odds is respectively only two and six times greater.

Table 10. Odds ratios and standard errors for men’s wage-earning capacity (logistic regressions)

|

Dependent variables |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|

|

Social group |

Higher managers and professionals (1) |

42.43351*** |

- |

|

(ref. Unskilled workers (6)) |

|

(14.41691) |

|

|

|

Lower managers (2) |

18.36562*** |

34.2565*** |

|

|

|

(4.743958) |

(26.77682) |

|

|

Foremen and skilled workers (3) |

16.43333*** |

9.969076** |

|

|

|

(4.189628) |

(6.923367) |

|

|

Farmers and fishermen (4) |

2.281615** |

- |

|

|

|

(0.7766638) |

|

|

|

Lower-skilled workers (5) |

6.424099*** |

3,886941 |

|

|

|

(1.819065) |

(2.903887) |

|

|

Lower-skilled and unskilled farmworkers (7) |

- |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Owners (8) |

47.32634*** |

- |

|

|

|

(24.01426) |

|

|

Age |

36 - 45 years |

0.9761184 |

0.5442808 |

|

(ref. 26 - 35 years) |

|

(0.1246053) |

(0.2457533) |

|

Agrarian towns |

0,1156413 |

- |

|

|

(ref. textile towns’) |

|

(0.1170791) |

|

|

|

Company towns |

1.23396 |

- |

|

|

|

(0.6025935) |

|

|

|

‘Other industries’ towns |

2.735491*** |

3.922715** |

|

|

|

(0.4573186) |

(2.42251) |

|

|

‘Mixed economies’ towns |

1.549176** |

2,296409 |

|

|

|

(0.241336) |

(1.872864) |

|

Number of children |

2 children |

1.253103 |

- |

|

(ref. 1 child) |

|

(0.1722884) |

|

|

|

3 children |

0.7601092 |

|

|

|

|

(0.1641134) |

|

|

|

4 or more children |

1.115541 |

|

|

|

|

(0.3033979) |

|

|

Wife’s wage range |

More than 10 pesetas/day |

|

29.45345** |

|

(ref. 4 – 4.99 pesetas/day) |

|

|

(32.06599) |

|

|

9.99 - 6 pesetas/day |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5.99 - 5 pesetas/day |

|

2,056998 |

|

|

|

|

(1.165614) |

|

|

Less than 4 pesetas/day |

|

1.281649 |

|

|

|

|

(0.6947136) |

|

N |

|

6186 |

932 |

Statistically significant values: *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05.

Source: Based on data extracted from the PADROCAT and BALL databases.

The age of the head of the family does not vary significantly, and so in terms of the life course our analysed population represents a homogeneous group. As regards the municipalities of residence, appropriately grouped, individuals who lived in municipalities classified under the headings of ‘other industries’ and ‘mixed economies’ were more likely to be able to cover daily needs than those who lived in textile-based municipalities: This suggests that the diversity of the economic activities in municipalities detailed in section 1 may have a positive impact on wage levels. This could be indicative of the consolidation of a diversified industrial economy in the context of the second industrial revolution. Equally, though, it may be a consequence of the fall in textile wages, as discussed above.

Perhaps contrary to expectations, the number of children was not a determining factor; that is to say, a greater number of children did not encourage men to seek higher wages, either because the market did not offer higher wages or because families resorted to other strategies to cover their needs. This underlines the importance of the economic contribution of women to family budgets, as mentioned in section 4. Along these lines, in model 2 we examine whether there was a positive relationship between male and female wages to reach the minimum of 11.74 pesetas per day (table 10). Even with a low number of women declaring wages, those who earned more than 10 pesetas per day had spouses who were 29 times more likely to be able to cover the family budget. This phenomenon is due to the effect of assortative mating, which reflects the human tendency to match with people of similar economic status, especially in groups with greater economic prospects. In this model, it is the lower managers and professionals, clerical and sales personnel (2) and the foremen and skilled workers (3) who show positive and significant odds of covering the family wage compared to the reference group of unskilled workers (6), confirming what had been seen in model 1; in fact, group 2 are 34 times more likely to cover their economic needs than group 6, and group 3 were nine times more likely to do so. However, women residing in municipalities with ‘other industries’ had husbands almost four times more likely to reach the daily minimum family wage compared to those living in municipalities dominated by the textile industry. This result could be explained by the existence of higher wages outside the textile sector. In all other municipalities no statistical significance is observed.

In summary, models 1 and 2 show that many of the independent variables considered are significant, and produce results consistent with the previous observations obtained using descriptive statistics.

6. The economies of families headed by widowers, widows and single women

Families made up of widowers or widows with young children (types 3c and 3d in Laslett’s classification) were a minority in these populations, since widowhood tended to be followed quite soon by second marriages or reunification with other family units, and the creation of extended or more complex families. The search for a broader kinship network able to take care of the children while the parents worked, or able to provide new resources, seems logical. Our data set includes only a small number of families in this situation: 36 households made up of widowers and 97 of widows, both with two inactive young children. Of these, 31 widowers (86%) and 49 widows (50.5%) declared a wage. Interestingly, more widows with young children declared a wage than adult women, among whom the rate was 20%. Despite the low number of this type of families, their results are very significant in the light of the discrepancies observed previously in relation to the purchasing power of wages whether considering only the wage of men, of men and women together, or only of women.

The budget for this type of family is calculated using the same criteria for food and the rest of expenses, in their aliquots, according to the information available. The cost of the daily budget for a single-parent family headed by a father is estimated at 5.85 pesetas per day (60% of that of a married family with two young children) and that of a single-parent family headed by a mother at 3.9 pesetas per day (46%). The lower cost of the shopping basket in the latter scenario is due to the lower cost of the woman’s diet, according to the FAO criteria (2004).

Table 11. Expenditure budget of single-parent families with children under 12 (in pesetas)

|

Budget |

Father with 2 children |

Mother with 2 children |

Adult woman living alone |

|

Food |

3.80 |

3.05 |

2.07 |

|

Housing |

0.38 |

0.38 |

0.25 |

|

Other |

0.91 |

0.49 |

0.37 |

|

Total |

5.85 |

3.92 |

2.69 |

Source: These data are from Borderías (2013 b).

Note: The diet corresponds to an optimal diet considering the sex and age of the different members of the three family types.

The significant wage inequality between men and women meant that, despite the lower cost of the shopping basket in families headed by a widow, the purchasing power of the wages of widowers was higher. Almost 40% of fathers but little more than a quarter of mothers could meet the family budget. Seventy-five per cent of fathers covered more than 80% of the budget, but only a little more than a third of mothers did so. In fact, very few families were in the most critical situation: only 6.5% of single-father households and 10% of single-mother households earned less than 60% of the income required for subsistence; but in this case, either other economic resources had to be sought or spending had to be reduced, with the ensuing risk of malnutrition and precariousness (tables 12 and 13).

Table 12. Range of budgets covered by widowed male heads of household declaring wages with children under or equal to 12 years of age and inactive (%)

|

HISCLASS groups |

30-59% |

60-79% |

80-99% |

=/+100 |

Total |

|||||

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

|

Higher managers and professionals (1) |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

100.0 |

1 |

100 |

|

Lower managers and professionals, clerical and sales personnel (2) |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

2 |

40.0 |

3 |

60.0 |

5 |

100 |

|

Foremen and skilled workers (3) |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

2 |

66.7 |

1 |

33.3 |

3 |

100 |

|

Farmers and fishermen (4) |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

25.0 |

2 |

50.0 |

1 |

25.0 |

4 |

100 |

|

Lower-skilled workers (5) |

1 |

12.5 |

2 |

25.0 |

2 |

25.0 |

3 |

37.5 |

8 |

100 |

|

Unskilled workers (6) |

0 |

0.0 |

3 |

33.3 |

3 |

33.3 |

3 |

33.3 |

9 |

100 |

|

Lower-skilled and unskilled farmworkers (7) |

1 |

100.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

100 |

|

Total |

2 |

6.5 |

6 |

19.4 |

11 |

35.5 |

12 |

38.7 |

31 |

100 |

Source: Based on data extracted from the PADROCAT and BALL databases.

Note: The sample corresponds to the male heads of single-parent families with inactive children under 12 years of age (3c families according to Laslett’s classification).

A result of special interest is the purchasing power of the female wage. As we have pointed out, the average wage for women (four pesetas a day) was more than enough to allow them to cover their own expenses and to be able to support themselves with their own means. Households formed by single women were a minority: 555 women, less than 1% of the adult female population. Sixty-seven per cent of female workers earned four pesetas or more. The minimum subsistence wage for an adult woman was 2.69 pesetas a day, a figure that 89% of female workers could achieve by working 265 days a year. Thus, in the case of marriage, most female wage earners contributed an amount sufficient to cover their own subsistence.

Table 13. Range of budgets covered by widowed female heads of household declaring wages with children under or equal to 12 years of age and inactive (%)

|

HISCLASS groups |

30-59% |

60-79% |

80-99% |

=/+100% |

Total |

|||||

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

N |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

|

Lower managers and professionals, clerical and sales personnel (2) |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

50.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

50.0 |

2 |

100 |

|

Farmers and fishermen (4) |

2 |

100.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

2 |

100 |

|

Lower-skilled workers (5) |

1 |

8.3 |

6 |

50.0 |

3 |

25.0 |

2 |

16.7 |

12 |

100 |

|

Unskilled workers (6) |

1 |

4.0 |

18 |

72.0 |

5 |

20.0 |

1 |

4.0 |

25 |

100 |

|

Lower-skilled and unskilled farmworkers (7) |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

100.0 |

1 |

100 |

|

Owners and rentiers (8)* |

1 |

14.3 |

2 |

28.6 |

0 |

0.0 |

4 |

57.1 |

7 |

100 |

|

Total |

5 |

10.2 |

27 |

55.1 |

8 |

16.3 |

9 |

18.4 |

49 |

100 |

Source: Based on data extracted from the PADROCAT and BALL databases.

Note: The sample corresponds to the female heads of households of single-mother families with children under 12 years of age who are inactive (3d families according to Laslett’s classification). * Included here are widowed heads of household who did not declare an occupation, but did earn a wage (i.e., property owners and rentiers).

7. Conclusions

Although the mobilizations of the Bolshevik triennium achieved a relative rise in wages in Spain, the effects of inflation continued to weigh heavily on workers’ economies. The scarcity of studies on living standards in Catalonia during this decade has left the historiographical debate open. This article provides new and solid evidence for this debate via the construction of family budgets. The sociodemographic data and information on occupation and wages of 88,068 individuals from 21,290 households have been extracted from the municipal registers of 24 municipalities in the provinces of Barcelona and Girona, with agrarian, industrial or mixed economies, and 12 textile company towns from all over Catalonia, in the year 1924. Our analysis of household economies is based on the types of families existing in the different locations and not on abstract family models; similarly, their occupations (classified according to HISCO and HISCLASS) and wages correspond to the structure of local labour markets. Finally, our assessment of consumption is based on local information and corresponds to a respectability basket that takes into account nutritional needs by sex and age, according to FAO parameters, and therefore ensures healthy living conditions.

Our results on the ability of the wages of adult male workers to cover the cost of a respectability basket in the mid-1920s reinforce the pessimistic interpretations of the decade in a very wide area throughout Catalonia. Although the improvement in living conditions compared to the second half of the nineteenth century is incontestable, the average coverage of the family budget by male heads of household was no higher than 63.1%, showing that a significant proportion of workers were unable to cover the basic needs of their family. Although the differences in terms of professional qualifications were significant, in some municipalities none of the heads of households earned enough to cover the needs of his family with his wages alone.

Just over 3% of agricultural and industrial day-labourers were able to cover the family budget. More importantly, this evidence extends to skilled workers, questioning the validity of the widespread notion of the existence of a labour aristocracy. Indeed, in the group Foremen and Skilled workers (group 3) – the paradigm of the labour aristocracy – only 11% corresponded to the sole male breadwinner model. In places with mixed economies, where the service sector was more developed and occupations were more diversified and higher-skilled, the figure of the sole male breadwinner was more frequent. Even so, the analysis by occupational groups shows that among Lower managers and professionals (2) this proportion was around a quarter, while even among Higher managers and professionals (group 1) less than half managed to earn the family wage.

The comparison with other European countries is complex due to the scarcity of international studies on the period in question, and due to the differences in the historical context. However, the data provided show that the dependence of the household economy on the wage of the head of the family was lower than in other countries; firstly, because rates of female employment were higher in many Catalan municipalities, especially in the textile industries (the context that predominates in international studies); secondly, because women’s wages were relatively high, especially in textile-based municipalities where the demand for female labour was strong. Hence, double-income economies, even when both spouses were in unskilled jobs, served the family budget more efficiently than single-income economies even if the male breadwinner was a skilled worker. In fact, 30% of widows, compared to 40% of widowers who declared a wage, were able to cover their family’s needs, and 89% of women who declared an occupation and wage could take care of themselves living alone; therefore, in the case of marriage, their contribution to the family economy was substantial. While 42% of heads of household covered between 60% and 80% of the budget and 15% managed to exceed 80%, when the wages of both spouses were combined, these proportions were reversed, reaching rates of 16% and 83% respectively. In contrast, 42% of men earned less than 60% of the amount needed to meet the family budget, only 2% of households were in this situation when both husband and wife worked.

Therefore, wherever women found opportunities to work, they did so, regardless of the prevailing ideological discourses. Possibly, self-provisioning helped to reduce wage deficits, but we have not been able to obtain any relevant data either on this issue or on the question of possible loans, transfers or other sources of aid. As for our calculations of potential savings during the first years of marriage, they appear to have been of some importance but do not seem sufficient to modify our results. It is clear that their wage deficits obliged families to implement strategies to supplement the wage of the head of the family – for instance, the entry of children into the labour market at any early age – but until this was possible, the wife’s wages were a more important resource than has been realized until now, and, in view of the evidence we provide here, were even more significant than in other countries.

References

ALABERT, Francisco (1914): Encarecimiento de la vida en los principales países de Europa y singularmente en España. Sus causas. Madrid, Establecimiento tipográfico de Jaime Ratés.

ALLEN, Robert. C. (2015): “The high wage economy and the industrial revolution: a restatement”, Economic History Review, 68 (1), pp. 1-22.

BALCELLS, Albert (1974): Trabajo industrial y organización obrera en la Cataluña contemporánea, 1900-1936. Barcelona, Laia.

BORDERÍAS, Cristina (2004): “Salarios y subsistencia de las trabajadoras y trabajadores de La España Industrial, 1849-1868”, Barcelona quaderns d’història, núm. 11, pp. 223-237.

BORDERÍAS, Cristina (2012): “La reconstrucción de la actividad femenina en Catalunya circa 1920”, Historia Contemporánea, 44, pp. 17-47.

BORDERÍAS, Cristina (2013a): “Salarios infantiles y presupuestos familiares en la Cataluña Obrera, 1856-1920”, in Borrás Llop, Jose María (ed.), El trabajo infantil en España (1750-1950). Barcelona, Icaria editorial, pp. 371-408.

BORDERÍAS, Cristina (2013b): “Revisiting Women’s labor force participation in Catalonia (1920-1936)”, Feminist Economics, vol. 19, n.º 4, pp. 224-242.

BORDERÍAS, Cristina (2021): “Budgets familiaux et salaires des ouvriers du textile de Barcelona (1856-1917)”, Le mouvement social, 276, pp. 151-170.

BORDERÍAS, Cristina; LÓPEZ GUALLAR, Pilar (2001): La teoría del salario obrero & la subestimación del trabajo femenino en Ildefonso Cerdà. Barcelona, Ajuntament de Barcelona.

BORDERÍAS, Cristina; LÓPEZ GUALLAR, Pilar (2003): “A gendered view of family budgets in mid-nineteenth century Barcelona”, Histoire et Mésure, 18, pp. 113-146.

BORDERÍAS, Cristina; FERRER-ALÒS, Llorenç (2017): “The stem family and industrialization in Catalonia (1900–1936)”, The History of the Family, 22 (1), pp. 34-56.

BORDERÍAS, Cristina; MUÑOZ-ABELEDO, Luisa (2018): “¿Quién llevaba el pan a casa en la España de 1924? Trabajo y economías familiares de jornaleros y pescadores en Cataluña y Galicia”, Revista de Historia Industrial, 74, pp. 77-106.

BORDERÍAS, Cristina; MUÑOZ-ABELEDO, Luisa; CUSSÓ-SEGURA, Xavier (2022): “Breadwinners in Spanish cities (1914-1930)”, Revista de Historia Industrial, 84, pp. 59-98.

BORDERÍAS, Cristina; CUSSÓ-SEGURA, Xavier (2023): “Male Wages, Household Budgets and Living Standards of Barcelona’s Working Class (1856-1917)”, Investigaciones de Historia Económica, 19, pp. 3-21.

BORRÁS LLOP, José María (ed.) (2013): El trabajo infantil en la España contemporánea (1750-1950). Barcelona, Icaria editorial.

BOTER, Corinne (2020): “Living standards and the life cycle: reconstructing household income and consumption in the early twentieth-century Netherlands”, Economic History Review, 73, pp. 1050–1073.

BURNETTE, Joyce (2024): “How not to measure the standard of living: Male wages, non-market production and household income in nineteenth-century Europe”, Economic History Review, DOI: 10.1111/ehr.13339.

CABRÉ, Anna (1989): La reproducció de les generacions catalanes, 1856 – 1960. Tesis Doctoral, Departamento de Geografía, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

CABRÉ, Anna and TORRENTS, Àngels (1991): “La elevada nupcialidad como posible desencadenante de la transición demográfica en Cataluña”, in GONZÁLVEZ PÉREZ, Vicente et al. Modelos regionales de la transición demográfica en España y Portugal. Actas del II Congreso de la Asociación de Demografía Histórica. Alicante, Institut Juan Gil Albert, pp. 99 – 120.

CACHINERO SÁNCHEZ, Benito (1982): “La evolución de la nupcialidad en España (1887-1975)”, Reis, 20, pp. 81-99.

CAMPS, Enriqueta (1991): “Els nivells de benestar al final del segle XIX. Ingrés i cicle de formació de les famílies a Sabadell (1890)”, Recerques: Història, economia i cultura, nº 24, pp. 7-21.

CAMPS, Enriqueta (2004): “A la recerca del temps perdut: homes, dones i nens al mercat de treball català al segle XIX”, in LLONCH, Montserrat, Treball tèxtil a la Catalunya Contemporània. Lleida, Pagès Editors, pp. 41-56.

CERDÀ, Ildefons (1867): “Monografía estadística de la clase obrera de Barcelona en 1856”, en Teoría general de la urbanización y aplicación de sus principios y doctrinas a la reforma y ensanche de Barcelona. Madrid, Imprenta Española, vol. II.

COLOMÉ, Josep; SAGUER, Enric; VICEDO, Enric (2002): “Las condiciones de reproducción económica de las unidades familiares campesinas en Cataluña a mediados del siglo XIX”, in MARTÍNEZ CARRIÓN, José Miguel (2002). El nivel de vida en la España rural, siglos XVIII-XX. Alicante, Universidad de Alicante, pp. 321-356.

CUSSÓ-SEGURA, Xavier (2005): “El estado nutritivo de la población española 1900-1970. Análisis de las necesidades y disponibilidades de nutrientes”, Historia Agraria: Revista de agricultura e historia rural, 36, pp. 329-358.

de MOOR, Tine; ZUIJDERDUIJN, Jaco. (2013): “Preferences of the poor: market participation and asset management of poor households in sixteenth-century Holland”, European Review of Economic History, 17, pp. 233–49.

DEL CAMPO, Salustiano; RODRÍGUEZ-BRIOSO, María del Mar (2002): “La gran transformación de la familia española durante la segunda mitad del siglo XX”, Reis, 100, pp. 103-165.

DEU, Esteve (1987): “Evolució de les condicions materials dels obrers sabadellencs de la industria llanera en el primer quart del segle xx”, Arraona, 1, pp. 43-49.

ENRECH, Carles (2004): “Conflictivitat, gènere i racionalització dels temps de treball (1891-1919)”, in LLONCH, Montserrat, Treball tèxtil a la Catalunya Contemporània. Lleida, Pagès Editors, pp. 95-112.

ENRECH, Carles (2005): Industria i ofici. Barcelona, Edicions de la Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona.

FAO (2004): Human Energy Requirements. Report of a Joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert consultation. Roma, Technical Report Series, pp. 17-24.

GABRIEL, Pere (1988): “Sous i cost de la vida a Catalunya a l’entorn dels anys de la Primera Guerra Mundial”, Recerques. Història, Economia i Cultura, 20, pp. 61-91.

GARCÍA ZÚÑIGA, Mario (2014): “Fêtes chômées et temps de travail en Espagne (1250–1900), in TERRIER Didier, MAITTE, Corinne (dir.), Les temps de travail. Normes, pratiques, évolutions (XIX-XXème siècles). Rennes, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, pp. 63-80.

GARRABOU, Ramon; RAMON-MUÑOZ, Josep Maria; TELLO, Enric (2015): “Organització social del treball, salaris i mercat laboral a Catalunya: el cas d’una explotació agrària de la comarca de la Segarra a la darreria del segle XIX”, Recerques, 70, pp. 83-123.

GIL-ALONSO, Fernando (2022): “Variación de los patrones geográficos en la fecundidad española. Variación de los patrones geográficos en la fecundidad española. Análisis retrospectivo a partir de los Censos de ١٩٢٠, ١٩٣٠ y ١٩٤٠”, Revista de Demografía Histórica-Journal of Iberoamerican Population Studies, 40 (1), pp. 192-22.

HORRELL, Sara; HUMPHRIES, Jane. (1992): “Old questions, new data, and alternative perspectives: Families living standards in the Industrial Revolution”, The Journal of Economic History, vol. 52, nº4, pp. 849-880.

HORRELL, Sara; HUMPHRIES, Jane (1995): “Women’s labour force participation and the transition to the male-breadwinner family, 1790-1865”, Economic History Review, 48, pp. 89–117.