Female genital mutilation: quantitative estimation of the problem in the European Union and qualitative analysis of its approach in Ireland, Italy, Spain and Sweden

Esther Portal Martínez, University of Castilla La Mancha

Juan Lirio Castro, Universidad de Castilla La Mancha

Enrique Arias Fernández, Universidad de Castilla La Mancha

Patricia Fernández de Castro, Universidad de Castilla La Mancha

Abstract

This paper is part of the results achieved by the Project “AFTER project, Against FGM/C Through Empowerment and Rejection” co-funded by the EU Rights, Equality and Citizenship Programme and implemented by a multidisciplinary Research Group based on Ireland, Italy, Sweden and Spain. The general objective is to contribute to the prevention and eradication of FGM/C and the specific objectives: a) To estimate the prevalence of FGM/C in the EU in order to size and make its scope visible b) To obtain a better and more in-depth understanding of how work related to FGM/C is approached in Ireland, Italy, Spain, and Sweden. A mixed research methodology was used. The quantitative approach allows for contextualizing and measuring the presence of this practice within EU territory, while the qualitative approach provides insights into and analysis of the experts’ perspectives on the policies that have been implemented. Results: The statistical analysis shows that the population from countries where FGM/C practised has increased in recent years. And the analysis of expert discourse shows agreement that is needed legislation to penalize the practice, but insufficient. It is necessary to developed prevention and comprehensive care measures for victims and inter-institutional coordination protocols, involving the participation of the affected communities. Professionals insist that relevant training is fundamental and ask for more resources and services, in addition to the creation of multidisciplinary teams. Conclusions: FGM/C is today practised globally, and eradicating it, requires engaging in real work to integrate the immigrant population and attend to its basic needs.

Key words: Female Genital Mutilation, Biopsychosocial consequences, Policies, Professional Approach, Awareness-Raising.

Mutilación genital femenina: estimación cuantitativa del problema en la Unión Europea y análisis cualitativo en el caso de Irlanda, Italia, España y Suecia

Resumen

Este artículo es parte de los resultados logrados por el proyecto “AFTER project, Against FGM/C Through Empowerment and Rejection” cofinanciado por el Programa de Derechos, Igualdad y Ciudadanía de la UE e implementado por un grupo de investigación multidisciplinario con sede en Irlanda, Italia y Suecia. y España. El objetivo general es contribuir a la prevención y erradicación de la mutilación genital femenina y los objetivos específicos: a) Estimar la prevalencia de la mutilación genital femenina en la UE para dimensionar y visibilizar su alcance b) Obtener una mejor y más comprensión profunda de cómo se aborda el trabajo relacionado con la mutilación genital femenina en Irlanda, Italia, España y Suecia. Se ha utilizado una metodología de investigación mixta. Cuantitativa para contextualizar y dimensionar la presencia de esta práctica en el territorio de la UE y cualitativa para conocer y analizar los discursos de los expertos sobre las políticas desplegadas. Resultados: La población originaria de países donde se practica MGF ha aumentado en los últimos años en la UE. Según el análisis de discursos, los entrevistados coinciden en que es necesaria la legislación que penaliza la práctica, pero no suficiente. Se precisa desarrollar medidas de prevención y atención integral a las víctimas y protocolos de coordinación interinstitucional que involucre la participación de las comunidades afectadas. Los profesionales insisten en que la formación es fundamental y piden más recursos y servicios, y la creación de equipos multidisciplinares. Conclusiones: La mutilación genital femenina se practica hoy en todo el mundo y erradicarla requiere un trabajo real para integrar a la población inmigrante y atender sus necesidades básicas.

Palabras clave: Mutilación genital femenina, consecuencias biopsicosociales, políticas, perspectiva profesional, sensibilización.

Fecha de recepción del original: 23 de enero de 2023; versión definitiva: 20 de septiembre de 2024.

- Esther Portal Martínez, University of Castilla La Mancha. E-mail: esther.portal@uclm.es

- Juan Lirio Castro, Universidad de Castilla La Mancha. E-mail: juan.lirio@uclm.es.

- Enrique Arias Fernández, Universidad de Castilla La Mancha. E-mail: enrique.afernandez@uclm.es

- Patricia Fernández de Castro, Universidad de Castilla La Mancha. E-mail: patricia.fernandez@uclm.es

Female genital mutilation: quantitative estimation of the problem in the European Union and qualitative analysis of its approach in Ireland, Italy, Spain and Sweden

Esther Portal Martínez, University of Castilla La Mancha

Juan Lirio Castro, Universidad de Castilla La Mancha

Enrique Arias Fernández, Universidad de Castilla La Mancha

Patricia Fernández de Castro, Universidad de Castilla La Mancha

1. Introduction

Women have been and continue to be subject to a wide variety of forms of violence. One such form is female genital mutilation or cutting (FGM/C), which consists of the partial or total cutting of the female genital organs, performed intentionally and for non-medical reasons (WHO 2018). This is a clear and serious violation of human rights and an act of extreme violence against women and girls. FGM/C is listed by the WHO (1979) as a harmful traditional practice (HTP); this list includes all practices that adversely affect the health of women, including child or forced marriage, infanticide, honour crimes or preference for male offspring.

As consequence of migratory movements, FGM/C is a phenomenon with global coverage, but in the case of the problem we are addressing here, the cultural differences between the host societies and the migrant population result in a problem that directly affects women’s rights. Being a practice that violates human rights, it is necessary to understand that the eradication of FGM is necessary, but also complicated, considering that it requires the implementation of measures in both the migrants’ societies of origin and the societies of destination (Mestre i Mestre, 2011).

This paper is the result of a mixed research conducted in Ireland, Italy, Spain and Sweden. Quantitative methodology aims to estimate how many women and girls have suffered, or are at risk of suffering, this HTP in the 28-UE, and qualitative methodology to provide stakeholders’ opinions regarding polices, services, resources and campaigns, in order to fight FGM/C and to understand and to improve women’s care. Further, with this paper, we try to contribute to the dissemination of knowledge of this practice.

2. Elements and forms of FGM/C

FGM/C is practised at varying ages. In Yemen, for example, babies are subjected to cutting during the first weeks of their lives, while in other communities FGM/C takes place before marriage or even after first giving birth. The most common period used to be between 5 and 14 years of age, as part of the rite of passage signalling the transition to adulthood. Currently, however, the majority of girls are mutilated before they reach the age of 5 years in order to avoid resistance and the problems arising from the illegality of FGM/C (UNAF 2015). It is more appropriate to refer to female genital mutilations, using the plural, because various types have been classified (WHO, 2018):

- Type I or clitoridectomy, involving the partial or total removal of the clitoris; this is the most difficult to identify in a medical examination.

- Type II or excision, with the partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora, and sometimes even the labia majora.

- Type III or infibulation, affecting the labia minora and/or majora, with or without excision of the clitoris, in addition to narrowing of the vaginal orifice by cutting and appositioning.

- Type IV, which is not precisely defined and includes a broad range of harmful procedures to the female genitalia that are difficult to classify, including pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterisation.

Although not all ethnic groups from a particular area practise FGM/C and when they do so there is diversity in terms of how it is done, we can make a general statement that, for example, in Western Africa it is more common to encounter type I and II mutilations, while type III is more common in the Eastern part of the same continent. When women or girls suffer type III mutilation, they have to be immobilised for up to 40 days with their legs tied together in order for the wounds to heal. Girls are also immobilised in some cases of type II mutilation, with a risk of causing fusion (the labia minora heal and there is fusing of the vaginal introitus as in the case of infibulation). In these cases, it is necessary to perform deinfibulation or reopening of the vaginal introitus in order to make sexual relations or childbirth possible.

3. Biopsychosocial consequences of FGM/C

In order to comprehend the dimensions and seriousness of the consequences of FGM/C, it should be understood that the cutting takes place in a highly vascularised area with a large concentration of nerve endings, which is therefore particularly sensitive to pain and subject to a high risk of haemorrhage. FGM/C is most commonly performed in highly precarious conditions. The person responsible for the cutting is usually someone without medical or anatomical expertise (the midwife, the circumciser or a grandmother of the child), with the use of imprecise instruments and little sterilisation (a razor blade, a knife, even glass or a can lid). On many occasions, various girls are cut with the same instrument, increasing the risk of infection (hepatitis, HIV). Measures to reduce bleeding or pain are generally restricted to applying cold water or administering local anaesthetic. Antiseptics and healing medication are limited to the use of ashes or herbal ointments. In some countries, such as Egypt, Guinea and Sudan, the practice has been medicalised (performed by health professionals in health institutions) to reduce risks and subsequent complications. But this has the effect of institutionalising and consolidating FGM/C and fails to prevent irreparable harm (Serour 2010, 2013).

This harm, which can even result in death, affects the physical, reproductive, psychological and emotional wellbeing of girls and women, in addition to their social development. The seriousness will depend on the type of mutilation, the extent to which cutting takes place, who performs the cutting and the conditions and instruments used. The consequences arise from the moment of cutting and last for the whole lifetime of those who are subjected to it. As mentioned, the most serious consequence of FGM/C is death, which can occur as a result of haemorrhage, the contracting of infections (tetanus, HIV, hepatitis) or obstetric complications during or after childbirth due to new haemorrhages (Gebremicheal, et al., 2018; Lavazzo et al., 2013).

Women who have suffered FGM/C commonly encounter difficulties with urinating, chronic urinary tract and genital infections caused by obstructions to the passing of urine or the menstrual flow, the production of bladder and urethral stones, kidney disorders, pelvic inflammation, fistulas, keratosis, fibrosis and persistent anaemia, frequently aggravated by poor nutrition. Strong and constant pain is experienced in addition to all of this (Ismail, et al., 2015; Kaplan et al., 2006; Lujan & Bethancourt, 2014; WHO, 2008, 2018).

Consequences for sexual and reproductive health include a significant risk of infertility resulting from harm to the reproductive organs, difficulties with coitus due to stenosis, lack of elasticity due to fibrosis, dyspareunia, dysmenorrhoea, hematocolpos, anorgasmia or at least reduced sexual appetite, increased cases of caesarean section and episiotomy to avoid lacerations and tearing during childbirth, increased foetal distress and the risk of perinatal mortality (Balachandran, et al., 2018; Berg, et al., 2014; Browning, et al., 2010; Isa, et al., 1999; Rushwan, 2013; Sylla et al., 2020). In type III mutilation cases and in type II fusing cases, deinfibulation has been necessary.

The physical consequences are interrelated with the psychological and social ones. Pain, chronic infections, kidney disorders, anaemia and other issues affect the normal course of girls and women’s private and social lives. Although there are fewer studies in this area and some are not conclusive, data have been recorded concerning issues such as anxiety, distress, depression, phobia, low self-esteem, shame, post-traumatic stress and reduced sexual appetite (Berg et al., 2010; Reisel & Creighton, 2015; Vloeberghs, et al. 2012; knipscheer et al., 2015). In a study conducted by Behrendt and Moritz (2005) with Senegalese women, it was found that among those who had been subjected to mutilation, almost 80% suffered from affective and anxiety-based disorders. There is also a high risk of post-traumatic stress disorder: around 30%, similar to that reported for victims of abuse during childhood.

It should be taken into account that FGM/C is socially presented as something that is positive and necessary, and that means one is joining the adult world. In places where it is a social norm or a sign of identity, a ceremony is usually held that the girl looks forward to in excitement; a party where there are often gifts and she is the centre of attention. These positive expectations conflict with the shock of the pain and suffering that will be experienced in reality. Added to this contradiction is the fact that the person who performs the cutting is someone who is respected in the community or very close to the girl.

Refusing the mutilation means being excluded from social integration in communities where social networks are fundamental to survival, but at the same time the repercussions of FGM/C can affect participation. For example, FGM/C tends to be a requirement for marriage, but infertility or difficulty in having coital relations as a result of cutting are grounds for divorcing or abandoning the woman.

It is necessary to add to all of the foregoing that girls and women have to bear all that happens to them in silence, as talking about the body, sexuality or the mutilation is often taboo. This makes it difficult for women to be able to process and understand what has happened and establish links between all the problems they are suffering and their cause, FGM/C.

4. International political framework to challenge and eradicate FGM/C

The potential conflicts between recognising cultural diversity and ensuring gender equality in different feminist arguments have been resolved from three different perspectives in contemporary societies: a) regulating the eradication of illegal practices; b) removing the individual concerned from their own group of origin (an approach that leaves the responsibility for “doing” in the hands of the individuals and entails the loss of their identity); c) working with communities and intercultural dialogue between them (Phillips and Dustin, 2004).

Today, whether due to its entrenchment in the traditions of certain places or as a result of migratory movements, FGM/C is a phenomenon on a global scale. In recent years, international work to secure its eradication has intensified. The Sustainable Development Goals were presented to the United Nations General Assembly in September 2015, to come into effect as from January 2016 (UN, 2015a). Goal Five, dedicated to the achievement of gender equality, expressly seeks the elimination of FGM by 2030. The Pan-African Parliament also committed to eradication in 2016, signing an agreement to ban FGM across its 55 Member States.). But despite all this work to eradicate FGM/C, it is estimated that 200 million women and girls may have suffered some kind of mutilation and 30 million are at risk (UNICEF 2016).

The European Union is also committed to this cause. In 2001, the European Parliament resolution on female genital mutilation (2001/2035(INI)) recognised FGM/C as a form of violence against women and a violation of human rights. The text describes the urgency of banning FGM/C and considering it a criminal offence in EU Member States, of punishing it as a criminal offence and of adopting comprehensive action strategies including prevention, assisting victims, raising awareness and providing training programmes. The European Parliament resolution of 24 March 2009 on combating female genital mutilation in the EU (2008/2071(INI)) called for the drawing up of an overall strategy, including preventive strategies in terms of social and healthcare actions.

The prohibition of the practice in host societies may be a necessary measure, but we believe that it is absolutely inadequate to address the set of problems that surround it. The regulation of the eradication of the practice requires the implementation of criminal measures, but also other prevention and assistance measures that are equally or even more important for its eradication. In this sense, in recent years, the EU’s involvement in the adoption of prevention and victim assistance measures has been more developed than in the first declarations on FGM/C.

The European Parliament Resolution of 14 June 2012 on ending female genital mutilation (2012/2684(RSP)) was adopted in 2012. It insists on the need to establish prevention and victim protection measures. In 2013, the EU undertook in the Communication from the European Commission “Towards the elimination of female genital mutilation” (COM(2013) 833 final) to allocated funds to combating FGM, promote sustainable social change for the abandonment of FGM focused on changing the attitudes and beliefs that underpin it, develop multidisciplinary cooperation, guarantee the protection of women at risk within the EU in accordance with the existing asylum legislative framework, and promote the worldwide eradication of FGM/C. The EU also undertook to improve understanding concerning the practice and to develop a common methodology and indicators to research and quantify the women at risk within the EU.

More recently, the EU has committed to the struggle to eradicate FGM/C on an international level through the Agenda for the achievement of the SDGs (UN, 2015b). Since 2017, it has been a signatory to the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence of 11 May 2011, more commonly known as the Istanbul Convention. Ratification of the Istanbul Convention makes it obligatory to adopt preventive and protective measures against the various forms of violence, including FGM/C.

5. National policies framework developed by the countries involved in this study, Ireland, Italy, Sweden and Spain, to eradicate FGM/C.

The international policies described in the previous section, constitute the general framework that Ireland, Italy, Spain and Sweden must consider and implement, as EU Member States, when addressing their work in relation to FGM/C. Fundamentally, measures for the eradication of FGM/C focus on three lines of intervention:

- The criminalization of FGM/C, leading to its prosecution and the establishment of penalties.

- Assistance to girls and women who have been victims or are at risk of undergoing this practice. This includes legal protection for minors, protection for asylum seekers or those granted refugee status (as FGM/C is a recognized ground for asylum), and for those who have already undergone mutilation, measures in the field of sexual and reproductive health, as well as psychosocial support.

- Prevention, which includes public awareness and education, professional training, and the promotion of research.

The four countries studied, Italy, Ireland, Spain, and Sweden (Table 1), have criminalized FGM/C, but there are differences in the instruments developed by each country for prevention and care. Italy has established comprehensive legislation to combat female genital mutilation, though there is a lack of development in certain areas of victim assistance and FGM/C prevention. In Ireland, some organizations had implemented measures to address this practice, but there was a regulatory gap, such as the absence of a government-led national plan with concrete measures. In Spain, the focus is primarily on the healthcare sector, with almost no measures adopted in other sectors like social or educational services. Additionally, preventive measures are scarce in the instruments analysed. Finally, although not regulated by law as in Italy, Sweden has the most comprehensive development of measures, thoroughly regulating care in the health, social, and educational sectors, and establishing concrete and significant actions for the prevention of FGM/C.

Table 1: National policies framework

|

IRELAND |

|

|

ITALY |

|

|

SPAIN |

|

|

SWEDEN |

|

Source: Authors’ own

6. Objectives and methodology

he general objective of this study is to contribute to the prevention and eradication of FGM/C, with the following specific objectives:

- To estimate the prevalence of FGM/C in the EU, particularly in the countries involved in this research, in order to size and make its scope visible.

- To obtain a better and more in-depth understanding of how work related to FGM/C is approached in Ireland, Italy, Spain, and Sweden

We used a mixed methodology in our research. The approach was quantitative for purposes of examining and analysing the data obtained from official secondary sources, and qualitative for purposes of exploring the perspectives and opinions of agents involved in the area of FGM/C, using interviews as an information-gathering technique.

In relation to the quantitative analysis, to identify the scope of FGM/C in Europe we used Eurostat, the statistical office of the European Union, as a source. There are no official records to show how many women and girls have suffered FGM/C, or the numbers of people who belong to communities that practise FGM/C, since at an official level only nationality is recorded, and in any single country there are people who maintain the practice and others who do not. For example, in Nigeria the Yoruba, Igbo and Edo practise FGM/C, but not the ljebu (Ismaili et al., 2015). For these reasons, we have to use indirect estimates in order to obtain an approximate reflection of reality. We obtained and analysed the data available from Eurostat in February 2019 for the period from 2014 to 2018. The following criteria were applied in extracting the information:

- General population recorded in Europe in 2018 who were nationals from one of the 30 countries in which there is FGM according to the UN (2016) (Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Ivory Coast, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Indonesia, Iraq, Kenya, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda and Yemen).

- Breakdown of population data by sex.

- Breakdown of population data by age, specifically girls aged from 0 to 15 years.

- Demographic evolution of study population for the period from 2014 to 2018.

- Distribution of study population by country of residence within the European Union.

The aim of the qualitative approach was to obtain better and more in-depth understanding of how work concerning FGM/C is approached in Ireland, Italy, Spain and Sweden. The AFTER project involved interviews with agents from the areas of health, social services, education and policy from May to September 2016. In total, 64 agents participated. They were asked about the FGM/C policy framework existing in each of their countries, the available sources, allocation of funds and the campaigns that had been carried out. Based on the responses, we conducted a qualitative analysis of the interviewees’ discourses and organised the content into three study categories corresponding to various contexts in which work is taking place to combat FGM/C:

- Structural/social context: exploration of knowledge and opinions on policies, services and resources aimed at identifying and eradicating FGM/C in the interviewee’s country and job location.

- Professional context: from a more practical perspective, collection of opinions on forms of intervention vis-à-vis FGM/C.

- Personal attitudes to FGM/C: analysis of interviewees’ awareness and attitudes regarding the issue of FGM/C and willingness to carry out work relating to the practice.

The majority of the interviewees were women, with only 4 male participants among the 64 people interviewed (Table 2). Ages ranged from 30 to 65 years, meaning that in general participants were employees with an extensive professional background, some having worked in various fields. Professionals working in healthcare, social services, education and policy were contacted due to our understanding that work relating to FGM/C involves at least these four areas. Not all interviewees had direct experience of working on FGM/C, but we were keen to identify perceptions among both experienced people and those who, due to the kind of work they performed, the population they assisted and the place in which they worked (geographical areas with immigrant residents from countries with prevalence of FGM/C), might have come into contact with but not identified this reality.

From the healthcare sector, interviews were conducted with 17 professionals specialising in gynaecology and obstetrics, paediatrics and family medicine, and community health. From social services, 27 professionals working in programmes relating to gender violence, sexual violence and migration and asylum were interviewed. Infant, primary, university and social education teachers (11 in total) were interviewed from the education sector. Finally, 9 interviews were carried out with technical consultants and policy makers representing the policy area.

Table 2: Classification and codification of interviewees

|

Areas |

Field / Programmes |

No. of interviews |

Code |

|

Health |

Gynaecology, obstetrics and reproductive and sexual health |

10 |

H1 |

|

Paediatrics and family |

4 |

H2 |

|

|

Community health |

3 |

H3 |

|

|

Social services |

Social welfare, children and families |

9 |

S1 |

|

Sexual violence and gender violence |

10 |

S2 |

|

|

Immigration and asylum |

8 |

S3 |

|

|

Education |

Infant, primary and university |

7 |

E1 |

|

Social education |

4 |

E2 |

|

|

Policy |

Technical consultants |

5 |

P1 |

|

Policy makers |

4 |

P2 |

7. Results

Firstly, we present the results of the quantitative analysis that will allow us to dimension and contextualize the phenomenon of FGM/C in the territory of the EU. And, secondly, the content analysis of the interviews.

It is difficult to estimate the amount of people from countries where FGM/C is prevalent who are resident in each of the 28 EU Member States, given that it would be necessary to add unlawful immigration (which it is highly difficult to calculate) to the official figures. It is necessary to add that there are countries such as India, Pakistan and Malaysia in which FGM/C is also practised but which are not included in the UNICEF report (2016) that we have used as a reference point, for which reason we have not included them in our research. Nor are people included who might belong to practising families or communities but have been born in a different country from the 30 listed in our study. Another criterion used in our study was to identify the total population of both men and women, since as we have seen, although this practice is directly suffered by women it is underpinned by patriarchal interests within communities where men have great power in terms of influence and decision-making. The eradication of FGM/C will hence only be possible through working toward conceptual change by involving men.

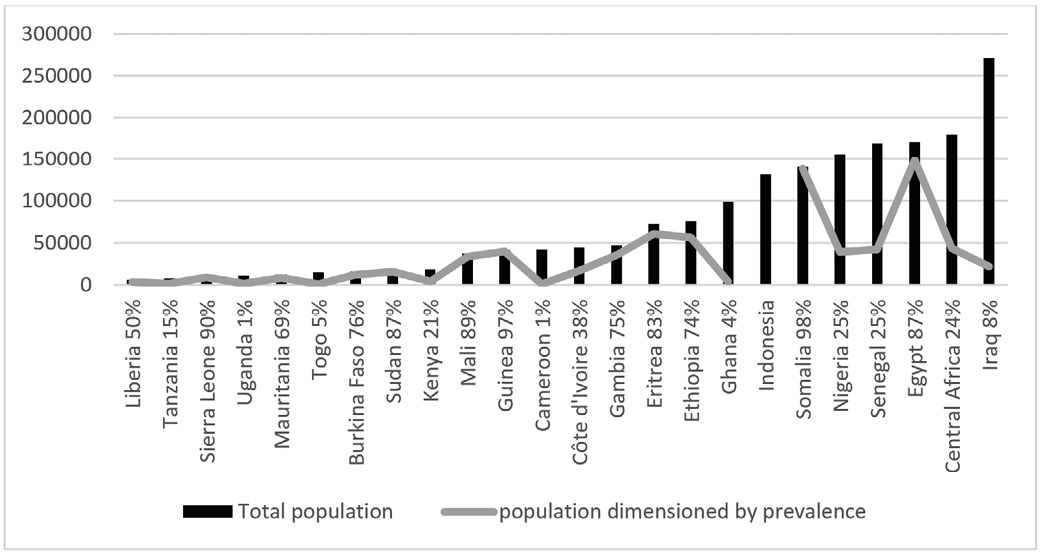

In 2018, 1,813,642 people were resident in the EU and had come from the 30 countries in which FGM/C is prevalent (Figure 1). Of this number, 737,691 were women, representing 41% of the total (Eurostat 2019). However, it is estimated that the population may be significantly higher as there are EU countries without data for 2018, making it necessary to resort to information from the 2011 census, in which, for example, the United Kingdom reported 276,805 people from countries with prevalence of FGM/C, with other figures including Germany 100,660, Greece 20,346, France 311,747, and Portugal 19,412 (Eurostat, 2018).

Figure 1: Population from countries with prevalence of FGM/C resident in EU-28

Source: Authors’ own, based on Eurostat data (2019)

An analysis of the last five years shows an increasing population from the countries included in the study. In 2013, there was a total of 1,319,648 people of whom 548,421 were female, while in 2017 the total reached 1,920,168 (810,945 women), for which year there is information for countries including the United Kingdom, which contributed 101,168 people, and Portugal, with 47,307 individuals (Eurostat, 2019). Total immigration therefore increased by 37% between 2014 and 2017.

Figure 2: Comparison of total population volume and population dimensioned by prevalence

Source: Authors’ own based on Eurostat data (2019) and the UNICEF prevalence index (2016)

Among migrants from countries where the practice of FGM/C is maintained, those with a notable presence within the EU-28 in 2018 were Iraq with 179,877 people, where the prevalence of FGM/C according to UNICEF (2016) is 8%, the Central African Republic with 179,877 people and 24% prevalence, Egypt with 171,064 and a prevalence of 87%, Senegal with 169,160 people and Nigeria with 156,182 people, both with a prevalence of 25%, and Somalia with 140,684 people and the highest level of prevalence at 98%. Figure 2 shows the total population resident in the EU-28 (direct figure in the bar chart), in addition to reflecting the population dimensioned according to the UNICEF prevalence index (2016) for girls and women aged between 15 and 49 years (line chart), except for Indonesia where there is only an estimate of 49% for girls aged under 15 years. We know that this index is in fact valid in the countries of origin, and no index has been produced for Europe. But the intention is to produce an estimate of the volume of both men and women who may influence or be exposed to the concepts that underpin FGM/C, whether through the nuclear family, the extended family or relationships with their community.

There is a shortage of data on girls aged under 15 years who may be at risk of or have already suffered FGM/C. Only 59,820 girls of this age have been recorded from any of the nationalities subject to study. We believe that the true number is higher, but many may have been born in the EU and they may have acquired the nationalities of the relevant EU Member State, depending on its specific legislation.

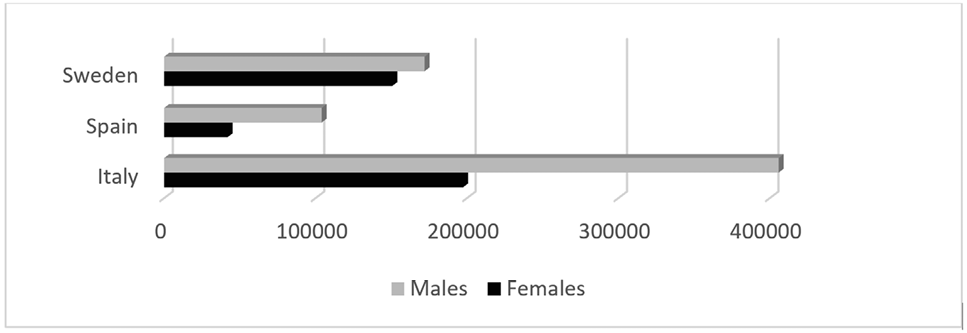

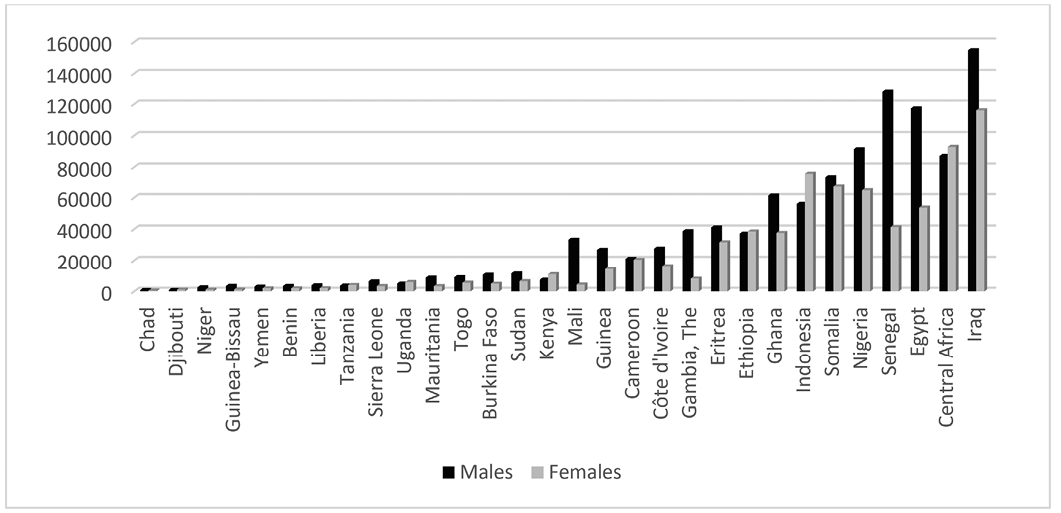

An analysis of the situation in Ireland, Italy, Spain and Sweden shows the last three having a total population of 1,072,261 people, of whom 390,267 are women (36%), for which reason the immigration can be described as predominantly masculine. Ireland is excluded from these data because none are available for 2018 (figure 3). The most recent figures available for Ireland relate to 2015, when 48,132 people were recorded (Eurostat, 2016). There are also differences if we consult national sources. For example, the figure in Spain amounts to 205,188 according to the Spanish National Institute of Statistics (INE, 2018), in contrast to the 146,050 people recorded in Eurostat. In any case, the Eurostat figure for 2018 (1,072,261) is very significant as these three countries alone make up 59% of the population from the 30 countries that maintain the practice of FGM/C: Italia contributes 603,415 people, Spain the aforementioned 146,050 and Sweden 322,796. Of this total, 34,782 are girls aged under 15 years.

Figure 3: Population from countries with prevalence of FGM/C resident in Italy, Sweden and Spain

Source: Authors’ own based on Eurostat data (2019).

The most populous group in Sweden was from Iraq (140,830 people), but we would draw the reader’s attention to the female population from Somalia (66,369), Eritrea (39,081) and Ethiopia (19,358), which in addition to being significant numbers of people, relate to countries with very high levels of FGM/C persistence, with percentages of 98%, 83% and 74%, respectively (UNICEF 2016).

Of note in Italy was the Egyptian population of 121,814, a country in which the prevalence of FGM/C is 87%, in addition to Nigeria with 92,495 and Senegal with 106,780 people, and 25% FGM/C prevalence in both cases. Of further interest due to the incidence of FGM/C and a significant population size were Ethiopia (28,260 people) and Somalia (12,829). Finally, turning to Spain, Senegal (52,579 people) and Nigeria (27,992) were the most populous countries, together with Mali with 17,124, Guinea with 9,938 and Mauritania with 8,339, the latter three with FGM/C prevalence of 89%, 97% and 69%, respectively.

To analyse the results of the 64 interviews, the information was structured into three categories: social/structural context, professional context, and personal attitude.

7.1. Social/Structural context.

Interviewees were asked about the legislation and policy regarding FGM/C in each country and region in which they worked. Although it is true that there are inequalities among the measures implemented by Ireland, Italy, Spain and Sweden, an analysis of the opinions expressed regarding legislation leads to the conclusion that there is a general lack of awareness except in cases in which the interviewee had played a key role in preparing documents, materials or protocols, or worked specifically on the issue. We also identified a certain difficulty in understanding legislative frameworks, although in all cases agents know that mutilation is a practice that is prohibited and punishable by imprisonment when a minor is cut.

As regards the existence of the punitive measures established in legislation, participants are in agreement that it is necessary “to know that there is a prison sentence, which could discourage parents from doing it to their children”, but not sufficient. There is a belief that preventive work is needed: “What can we do with the parents in prison, once the girl has been mutilated?” (H1). The opinion is also expressed that the existence of prison sentences could be useful and might act as a justification for parents who did not wish to acquiesce to pressure from extended family or community, because “prison is usually heavily frowned upon among these populations” (H1); “for Africans, going to prison is a humiliation for the whole family” (S1).

However, the discourse is dichotomised in terms of the application of these laws and how they can interfere with care work. Some stakeholders believe it necessary to comply with the measures established and to punish whoever commits or collaborates in committing the offence, and that there should hence be no hesitation in reporting cases that are identified, since irreparable harm has been done to the girl. Some of those who adopt this position believe that evidence of the law not working properly is found in the scarcity of cases that reach the courts, with more effort required in terms of prosecuting the offence.

Those who believe the law should be applied without qualifications and even that tougher punishments should be established maintain a clear and decisive attitude. They do not consider that distinctions should be made or other factors should be taken into account when faced with a case of FGM/C; rather, they argue that it should be treated in the same way as any other kind of violence, with parents facing the loss of custody of their children or even imprisonment. These participants classify safeguarding the personal integrity of girls as the priority and believe that reporting FGM/C cases can help to make the problem more visible.

Another group of agents think that when there are few or no preventive measures, the problem may be aggravated. For example, girls may be sent to their countries of origin to live there until they are of legal age, in an environment that is alien to them and suffering the loss of attachment relationships and educational opportunities, to later return mutilated and even married. Another negative outcome that these agents describe is that a family may become suspicious at a health clinic, for example, and decide not to return for future appointments, depriving girls and women of medical support and supervision. This would entail a loss of rights for girls and result in their being excluded even further: “if you only punish, the effect is to push people into hiding, which means greater danger for the girls” (S2).

In this case, interviewees believe that there could be a risky interpretation of the fact that few cases have reached the courts: “if there are no cases involving FGM/C, it will be thought that we have resolved the problem” (S3). They warn of the restrictive nature of the current laws that prosecute the offence and insist that the focus should be on preventive efforts. In order to achieve this, they believe it necessary to produce intervention protocols and create institutional communication channels that cover at least the health, social services and education systems. These interviewees also argue that the communities themselves should participate in the production of mechanisms and protocols. They consider it fundamental to use cultural mediators in order to work with the communities and general, and with those who have community leadership roles in particular: “sexuality and FGM are taboo topics. Awareness needs to be raised and it has to be done by African people, because it is very difficult for them to trust someone who is an outsider” (S2). In general, the only value that they can see in criminal sentencing is that of making an example of someone.

An analysis of information by country reveals Italian stakeholders to be those who place most value on their country’s policy framework for addressing FGM/C. They consider that Italy has good national legislation, with one interviewee even categorising it as excellent (H3). However, there is recognition that this law may be useful in the medium-to-long term, with second generations, and that prevention necessarily entails working with and from the relevant communities.

Agents refer to a lack of mechanisms in Ireland, asking for a national strategy to be drawn up to address FGM/C and also: “To transpose the EU Victims Directive into Irish law and ratify the Istanbul Convention” (S2). One Swedish stakeholder believes that “there should be a serious debate on FGM/C” (S2) to develop policies. In general, there are requests to “improve the gender approach in the laws” (E2) and for greater efforts to develop strategies and protocols. Participants also demand the implementation of care policies for women who have already been mutilated.

In Spain, some experts criticise the absence of a coherent nationwide programme or strategy. There is agreement with the position that work has taken place to address the problem, but it is seen as having occurred in a dispersed manner and very frequently at the initiative of NGOs, and has not been a priority in terms of policy implementation. This would partly explain the levels of general ignorance of this issue. The fact that the affected population tends to be geographically concentrated would also contribute to this general ignorance.

By area, although some interviewees were unaware of the policy framework, professionals working in health-related areas have the most knowledge of policy, and particularly those working in gynaecology and obstetrics. This coincides with the fact that all four countries (Ireland, Italy, Spain and Sweden) have implemented specific mechanisms in the health sector, while there are variations from one country to another in the other sectors. For example, in 2016 only Ireland and Spain had implemented measures with regard to minors, and in terms of gender violence, Italy, Spain and Sweden had recognised FGM/C as another form of mistreatment or violence. As stated in the interviewee profile, not all agents worked directly on the issue of FGM/C and some had only done so sporadically. Together with the difficulties in identifying cases in which FGM/C has already taken place and assessing those who are at risk, this lack of contact, particularly in the social services and education sectors, may explain the ignorance regarding laws and mechanisms. We find certain critical stances in the policy sector, Some think that the legal regulations are limited and highly sentence-focused: “it appears that the actions are aimed at sentencing and essentially at prosecution… at communities understanding that a crime is being committed. But are we going to work towards communities becoming aware of what the practice means?” (P1)

Almost all interviewees, regardless of the country in which they work or their professional area, refer to the recurring issue of the absence or scarcity of assessments regarding the policies implemented. This hinders or prevents an understanding of whether the laws and mechanisms are working, how effective they are and if they could be improved.

When interviewees were asked about the campaigns conducted with relation to FGM/C, the general idea was that they are scarce and very scattered. In general, interviewees identified the International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation on 6 February and some actions carried out on that occasion, but they described these actions as merely symbolic. Stakeholders in Italy, Sweden and Spain believe that the campaigns tend to be excessively Westernised and are not directed at and do not actually reach the population among which FGM/C remains prevalent, but rather focus on the European population. For the Italian experts, this is what explains the failure of the campaigns carried out in the region of Lombardy. Again, there is criticism of the failure to assess the campaigns to identify their impact and whether their objectives were achieved. In Ireland, an interviewee states that the campaigns should be “at a national and multidisciplinary level, aimed at and translated into the languages of the groups that practise FGM/C” (H1) to ensure that they reach the whole population. Another agent in Spain adds that “to avoid stigma, [campaigns] should be linked to other issues such as the right to personal integrity, employment, health, sexuality” (H1)

7.2. Professional context

One outcome from the discourse analysis is that directly addressing the reality of FGM/C has been the key element for interviewees involved in the area. Stakeholders with more experience of FGM/C observe that there has been more institutional effort made in recent years to raise awareness of the practice and that training courses were being provided. However, their view is that these courses are too basic and focus more on awareness-raising than on actual training.

There is also criticism across all four countries that in spite of the recent work, official reaction has been slow and somewhat superficial, without considering fundamental issues such as production of protocols to coordinate services and institutions. Agents also believe that work has been left to NGOs, which have taken the initiative in terms of developing programmes, and to professionals who have taken the personal and voluntary decision to involve themselves in the issue. There is a demand that “governments have to commit themselves” (S2).

Those with most expertise consider that the FGM/C problem has not been approached from a comprehensive perspective and argue that all its dimensions should be taken into account, ranging from a consideration of the reasons underpinning this practice (health-related beliefs, the patriarchal system, culture and tradition) to offering care to women on all levels, bearing in mind that the consequences of FGM/C are physical, psychological and social.

Social services agents state that community work is fundamental in helping parents who do not wish to mutilate their children to defend their views against the opinions of their community or extended family. But they explain the difficulty of reaching those who are determined to practise FGM/C and explain that on many occasions they are working with people who are opposed to the practice: “we meet with women who are already aware, we don’t work with those who are doing the mutilating. We prosecute them, but we don’t work with them to achieve change” (H3).

In Spain, there is an observation that “parents do not participate much at school” (E1). Moreover, African immigrants occasionally resort to social services to seek some help but do not make other requests that would make ongoing work possible. Agents in Spain also state that there is a need to work on fundamental matters when accommodating immigrants and asylum seekers, such as ensuring that their basic needs are covered, while FGM/C represents a secondary problem for them given that they are focused on survival.

There is criticism in Sweden and Spain of the contradiction between seeking to eradicate FGM/C, which implies giving care to women who have already been mutilated and preventing their suffering, and at the same time refusing access to the healthcare system for illegal immigrants or asylum seekers. The conclusion here is that without carrying out real work to achieve inclusion, it is hard to make progress in securing the abandonment of FGM/C.

One aspect that stands out in the discourse of all four countries is training. Interviewees maintain that there is little knowledge on FGM/C across all areas and professional categories. This is seen as a serious problem in Sweden. There is agreement across all four countries that various training courses are required, from a basic level involving awareness-raising, developing knowledge of the practice, learning to detect it and disseminate the use of protocols, to an in-depth or expert level that enables professionals to address the issue with men, women, families and communities. For example, in the healthcare area agents state that it is difficult to detect type I mutilation during gynaecological examination of women if one does not specifically look for it: “When we started to train professionals, there were people who had not even considered a complex examination of the genitals to see if they were mutilated … We don’t detect it because we don’t even look for it … The first action is to make it visible, not only in healthcare but also in the educational setting, because there are girls at risk” (H3). They add that this is undoubtedly more difficult for paediatric nurses, who have to monitor the girls. The agents consider that training should be included as part of the university studies of future doctors and nurses: “Nursing schools should provide training on what FGM/C is and how to combat it. That would help to prevent it” (H1). Along these lines, we spoke to some agents who had incorporated FGM/C into the topics studied in their classes.

Healthcare experts in Spain request community work training, believing that it should be included in university programmes as they consider such work necessary for the prevention of FGM/C and to address other problems. In terms of social tools and skills, some interviewees also emphasise the difficulty of addressing the topic of FGM/C in a respectful manner, without creating discomfort or showing disrespect when the issue is taboo and without causing misgivings that could frighten women or families away from consultations.

In the social services and educational sectors, agents find particular difficulties in working and especially in preventing FGM/C, since as they state it is a hidden practice; a private issue shrouded in secrecy and an element of fear. They recognise that in general they are not even qualified to talk about FGM/C. These agents express the need to receive more training on intercultural issues and knowledge of traditions.

In Ireland, for example, where agents describe a clear lack of training, there are professionals who have not detected any cases of FGM/C despite working with immigrants from countries where it is prevalent, whether in sexual health, gender violence, sexual violence or asylum programmes. Some interviewees attribute this situation to a lack of knowledge or tools to detect and address the issue.

Interviewees in Ireland, Sweden and Spain also point to a lack of education among practising communities: “They still don’t know how bad it is for the girls’ health; the prevailing belief is that it’s good for them” (S2). They propose the implementation of education programmes with immigrant communities in order to make them aware of the law and the biopsychosocial consequences of FGM/C. A further suggestion is to train mediators to work with practising communities.

With relation to the services and resources allocated to FGM/C, there is a unanimous view that more resources are needed and that the existing ones are clearly insufficient. Added to this, there is considerable inequality in terms of distribution of services with services geographically located in major cities and not all cities having support services or care and prevention units. Interviewees think that more funds are required to work on the problem, in terms of both caring for women and girls and preventing FGM/C.

Didactic materials have been created and distributed in schools in Sweden, but in general it is felt that materials for use as guides or brochures to be disseminated in health clinics, hospitals, schools or police stations are few and far between. Faced with this lack of specific resources in Spain, for example, some professionals have formed teams and developed action protocols in the healthcare sector. Across all four countries, professionals from various sectors talk of the need to create multidisciplinary teams that include intercultural mediators, this being the most effective way to tackle the problem.

7.3. Personal attitude to FGM/C

Regardless of their country and professional sector, all interviewees showed themselves to be receptive and sensitive with regard to FGM/C. Those who have yet to work on FGM/C also state their willingness to do so, with those having greater current knowledge being keen to further improve their expertise.

In general, we can state that people who are more involved in FGM/C work have a more complex view of how the problem should be addressed. This is reflected, for example, in discourse regarding the number of agents whose involvement is thought to be required in terms of both prevention and care, and in a comprehensive understanding of how FGM/C affects life plans in terms of the clear physical harm with negative consequences for sexual and reproductive health, but also in psychological, emotional and social terms. Agents also express the view that this work should be linked to the living conditions of the relevant girls, women and communities.

A common feature among the experts who are most heavily involved in this area is the questioning of their own limitations. This relates to professional limitations, with experts pointing to the need to carry out community work and to create multidisciplinary teams. It also refers to the personal level, with interviewees considering how to address the matter in a respectful manner, without imposing Western culture and ensuring that work is consistent. One interviewee is self-critical, for example, in admitting: “We have not had enough empathy with the communities” (H3).

The interviewees also coincide with regard to the personal and professional origins of their motivations: many of them voluntarily involved themselves in the issue of FGM/C after encountering a reality of which they had been unaware; for example, at a medical consultation. Based on this type of circumstance, agents independently began to investigate and to educate themselves, monitored women, and produced unofficial statistics. In light of a lack of institutional protocols in the case of Spain, for example, agents even produced their own action protocols, provided training and developed teams.

In other cases, the motivation and interest is a result of agents’ own personal experience of having suffered mutilation and having to live with its physical, psychological and social consequences. Becoming aware of how FGM/C has affected their lives has driven these agents to play an active role in the fight to eradicate it, and to ensure that the women and girls who have been subjected to it receive comprehensive care in terms of all their resulting needs.

8. Discussion and conclusions

FGM/C is a violation of the rights of women and girls, with serious physical, psychological and social consequences. The task of preventing and eradicating FGM/C is a complex one, since it is grounded in strong and deep-rooted beliefs. There is a need for a conceptual shift that necessarily involves men and women, as although FGM/C is a practice to which women are subjected, it is a control mechanism underpinned by patriarchal interests.

FGM/C is today practised globally, whether due to tradition or immigration, although it remains somewhat invisible due to being restricted to private practice. For this reason, it is necessary to make an effort to establish its spread. According to the results of this study, there are at least 1,813,642 people resident in the EU who are from countries in which FGM/C is prevalent, of whom 737,601 are women and 59,820 are girls aged under 15 years. This population has increased by 37% since 2014 (Eurostat, 2019). However, these figures may be significantly higher as not all EU countries have provided up-to-date information for this source. The EU must therefore maintain a strong commitment by implementing policies and allocating funds for prevention and eradication, research and care for the victims of FGM/C. It is necessary to identify communities where FGM/C is practised and to draw up medicals records of women who suffered it. A limitation that we have found to measure the scope of the problem is that there are no official records and we have had to resort to secondary sources

Italy (with 603,415 residents), Spain (146,050) and Sweden (390,267) account for 59% of that population, amounting to 1,072,261 people (390,267 of whom are women, and 34,782 of whom are girls). Ireland only has data for 2016 (recording 48,132 people), which has not been updated for 2018. Due to these figures, these countries in particular must take responsibility for understanding and tackling this situation.

Our analysis of expert discourse shows controversy as regards the application of punitive measures. Though interviewees agree that there is a need for legislation to penalise the practice, they see it as insufficient on its own. The proposal is to develop prevention and comprehensive care measures for victims as well as intervention and inter-institutional coordination protocols, involving the participation of cultural mediators and necessarily the involvement of affected communities in the development process. Agents also ask for policies and campaigns to be assessed. In line with this idea and as we have pointed out, the regulation of the eradication of the practice cannot stop at the mere criminalisation of the practice. Prevention measures, as well as assistance measures are even more necessary, but, as the results of this research reveal, in deciding on the most appropriate measures it is necessary to question not only practical but also ethical aspects related to cultural differences and the cultural pluralism present in the receiving societies. The connotation of the affected communities and the searching for intercultural dialogue is fundamental.

At a professional level, agents believe that to eradicate FGM/C it is necessary to engage in real work to integrate the immigrant population and attend to its basic needs, because as long as this group faces difficulty in surviving, FGM/C and its consequences will be very much a secondary consideration. Professionals insist that relevant training is fundamental, and some propose that it be included as part of university courses. Interviewees suggest establishing various levels of training, ranging from a basic awareness-raising course to an expert level to handle FGM/C work with the whole target population.

Agents also ask for more resources and services, in addition to the creation of multidisciplinary teams with professionals from the health, social services and education sectors and mediators to tackle the problem in close contact with the affected communities. In line with the feminist approach pointed to promoting intercultural dialogue between groups proposed by Phillips and Dustin (2004), regulating the eradication of GFM/C in host countries involves supporting the work that members of migrant communities are doing (Mestre i Mestre, 2011).

As regards agents’ attitudes, we must emphasise the sensitivity and receptiveness they have shown with respect to this issue and their willingness to collaborate. Those with most experience of FGM/C are very committed people, who generally display a more complex and better understanding of the practice.

Finally, to gain a more comprehensive perspective, and despite the challenge posed by the fact that it remains a taboo subject, it would be essential to include the opinions of communities where FGM/C is prevalent, particularly the views of women who have experienced it or are at risk. Their insights on the policies that have been implemented, how to improve them, and what new measures should be developed are crucial. Additionally, it would be valuable to identify, analyse, and compare innovative experiences launched by public institutions or NGOs that have obtained positive results, while avoiding past mistakes.

References

BALACHANDRAN, Aswini, DUVALLA, Swapna, SULTAN, Abdul H. & THAKAR, Ranee (2018): “Are obstetric outcomes affected by female genital mutilation?” International Urogymecology Journal, 29, pp. 339-344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-017-3466-5

BEHRENDT, Alice & MORITZ, Steffen (2005): “Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Memory Problems After Female Genital Mutilation”. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, pp. 1000-1002.

BERG, Rigmor C., DENISON, Eva & FRETHEIM, Atle (2010): “Psychological, Social and Sexual Consequences of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C): A Systematic Review of Quantitative Studies”. Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services,13. https://www.fhi.no/globalassets/dokumenterfiler/rapporter/2010/rapport_2010_13_fgmc_kjonnslemlestelse.pdf

BERG, Rigmor C., ODGAARD-JENSEN, Jan, FRETHEIM, Atle, UNDERLAND, Vigdis. & VIST, G. (2014): “An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Obstetric Consequences of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting”. Obstetrics and Gynecology International, 2014; https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/542859

BROWNING, Andrew, ALLSWORTH, Jenifer E., and WALL, L.Lewis (2010): “The relationship between Female Genital Cutting and Obstetric Fistulas”. Obstet Gynecol, 115(3), pp. 578-583.

Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council. Toward the elimination of female genital mutilation (2013): (COM/2013/0833final) https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52013DC0833

Council of Europe (2011): “Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence (Istanbul Convention)”. https://www.coe.int/en/web/gender-matters/council-of-europe-convention-on-preventing-and-combating-violence-against-women-and-domestic-violence

European Parliament (2001): “Resolution on female genital mutilation (2001/2035(INI)”. Official Journal of the European Communities. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/5dd0b2f0-1a46-421c-8fc8-4c2e5040beb2

European Parliament (2014): “Resolution of 24 March 2009 on combating female genital mutilation in the EU (2008/2071(INI))”. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52009IP0161

European Parliament (2012): “Resolution of 14 June 2012 on ending female genital mutilation (2012/2684(RSP))”. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-ontent/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52012IP0261

EUROSTAT (2019): https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database

GEBREMICHEAL, Kiros, ALEMSEGED, Fisehaye, EWUNETU, Haimanot, TOLOSSA, Daniel, MA’ALIN, Abdibari, YEWONDEWESSEN, Mahlet & MELAKU, Samuel (2018): “Sequela of female genital mutilation on birth outcomes in Jijiga town, Ethiopian Somali region: a prospective cohort study”. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 18 (٣٠٥). https://doi.org/١٠.١١٨٦/s١٢٨٨٤-٠١٨-١٩٣٧-٤

Instituto Nacional de Estadística (2019): www.ine.es

ISA, Rahman, SHUIB, Rashidah & OTHMAN, M. Shukri (1999): “The Practice of Female Circumcision among Muslims in Kelantan, Malaysia”. Reproductive Health Matters, 7(13), pp. 137-144. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(99)90125-8

ISMAIL, Asha, De DIOS, Begoña & GASCÓN, María (2015): Prevención y erradicación de la mutilación genital femenina. Manual para la intervención social con un enfoque intercultural y de género. Madrid, Acción en Red & Save a Girl, Save a Generation.

KNIPSCHEER, Jeroen, VLOEBERGHS, Erick, KWAAK, Anke & MUIJSENBERGH, Maria (2015): “Mental health problems associated with female genital mutilation”. BJPsych Bulletin; 39(6), pp. 273–277.

KAPLAN, Adriana, TORÁN, Peré, BERMÚDEZ, Kira & CASTANY, Mª José (2006): “Las mutilaciones genitales femeninas en España: Posibilidades de prevención desde los ámbitos de la atención primaria de salud, la educación y los servicios sociales”. Migraciones, 19, pp. 189-217.

LAVAZZO, Christos, SARDI, Thalia A., & GKEGKES, Ioannis D. (2013): “Female genital mutilation and infections: a systematic review of the clinical evidence”. Arch Gynecol Obstet, 287, pp. 1137-1149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-012-2708-5

LUJAN, Yusimi & BETANCOURT, Pablo Ricardo (2014): “Mutilación genital femenina y sus complicaciones a largo plazo”. Revista Humanidades Médicas, 14 (3), pp. 602-614. http://ref.scielo.org/tcr22h

MESTRE i MESTRE, Ruth (2011): “La mutilación genital femenina (MGF) en el contexto europeo: qué se ha hecho y qué se puede hacer”. In Ricardo Rodríguez & Encarna Bodelón, Las violencias machistas contra las mujeres, pp. 57-74. Barcelona, Bellaterra

PHILLIPS, Anne y DUSTIN, Moira (2004): “UK initiatives on forced marriage: regulation, dialogue and exit”. Political Studies, 52 (3), pp. 531-551. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2004.00494.x

REISEL, Dan & CREIGHTON, Sarah M. (2015): “Long term health consequences of Female Genital Mutilation (FGM)”. Maturitas, 80(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.10.009http://www.jstor.org/stable/3775716

RUSHWAN, Hamid. (2013): “Female genital mutilation: a tragedy for women’s reproductive health”. African Journal of Urology, 19, pp. 130-133

SEROUR, Gamal I. (2010): “The issue of reinfibulation”. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 109(2), pp. 93-96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.01.001

SEROUR, Gamal I. (2013): “Medicalization of female genital mutilation/cutting”. African Journal of Urology 19, pp. 145–149

SYLLA, Fatoumata, MOREAU, Caroline & ANDRO, Armelle (2020): “A systematic review and meta-analysis of the consequences of female genital mutilation on maternal and perinatal health outcomes in European and Africans countries”. BMJ Global Health, 5. https://gh.bmj.com/content/5/12/e003307

UN (2015a): Sustainable Development Goals. http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/summit/

UN (2015b): Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Resolution Adopted by General Assembly on 25 September 2015, 42809, 1-13.

UNAF (2015): Guía para profesionales. La MGF en España. Prevención e intervención. Madrid, UNAF-Unión Nacional de Asociaciones Familiares.

UNICEF (2016): Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A Global Concern. http://data.unicef.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/FGMC-2016-brochure_250.pdf

UNPFA (2016): Ending Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) and Chid Marriage. The Role of Parlamentarians. https://kenya.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/UNFPA-PAP%20Workshop%20on%20Ending%20FGM%20-%20FINAL%20Report%20%281%29.pdf

VLOEBERGHS, Erick, van der KWAAK, Anke, KNIPSCHEER, Jeroen, & van den MUIJSENBERGH, Maria (2012): “Coping and chronic psychosocial consequences of female genital mutilation in the Netherlands”. Ethnicity Health, 17, pp. 677-95, 10.1080/13557858.2013.771148

WHO (1979): Seminar on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/14505

WHO (2008): Eliminating female genital mutilation: An interagency statement, http://www.unfpa.org/webdav/site/global/shared/documents/publications/2008/eliminating_fgm.pdf

WHO (2018): Classification of female genital mutilation. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/fgm/overview/es/