The student as human capital in secondary education: an analysis of the impact of socio-demographic variables on the perception of learning.

Francisco Javier Trigueros-Cano, Universidad de Murcia

José María Álvarez-Martínez-Iglesias, Universidad de Murcia

Jesús Molina-Saorín, Universidad de Murcia

María Victoria Zaragoza-Vidal, Universidad de Murcia

Abstract

Spain (statistically and at European level) occupies the top positions among the countries with the highest school dropout rates; and along the same lines, various studies (INE, 2020; Vaquero, 2011) confirm that teachers in our country consider that education must be transformed to ensure that all students feel that they are the protagonists of the learning process; and that - in addition - everything they learn can be transferred to develop as citizens to the extent that their needs are also met (Álvarez et al., 2020:20). In this sense, it is absolutely necessary to know (through the student’s perception) to what extent the socio-demographic variables that students present intervene and condition the learning process and its transfer. For this purpose, a purposive sample has been configured in which more than 1,400 4th ESO subjects (from Spain) have participated, with a significance level of 0.05 using a scale -original and unpublished- called EPECOCISO (Evaluation of the perception of social science competences -Álvarez, Trigueros, Miralles and Molina, 2020-).

Key word: teaching, learning, social sciences, teacher training, inclusive education, teacher training, inclusive education

El estudiante como capital humano en la educación secundaria: un análisis del impacto de variables sociodemográficas en la percepción del aprendizaje

Resumen

España (estadísticamente y a nivel europeo) ocupa las primeras posiciones de los países con mayores tasas de abandono escolar; y en esa misma línea diversos estudios (INE, 2020:155; Vaquero, 2011:3) constatan que los docentes en nuestro país consideran que la educación debe transformarse para hacer que todos los alumnos lleguen a sentirse protagonistas del proceso de aprendizaje; y que –además– todo lo aprendido pueda ser transferido para desarrollarse como ciudadanos en la medida que también satisfagan sus necesidades (Álvarez et al., 2020:4). En este sentido, resulta del todo necesario conocer (a través de la percepción del estudiante) en qué medida las variables sociodemográficas que presenta el alumnado intervienen y condicionan al proceso de aprendizaje y su transferencia. Para ello, se ha configurado un muestreo intencional en el que han participado más de 1400 sujetos de 4.º de ESO (de España), con un nivel de significatividad de 0,05 utilizando una escala –original e inédita– denominada EPECOCISO (Evaluación de la percepción sobre las competencias de ciencias sociales –Álvarez, Trigueros, Miralles y Molina, 2020:1-15–).

Palabras clave: enseñanza, aprendizaje, Ciencias Sociales, formación del profesorado, educación inclusiva

Original reception date: June 15, 2022; final version: April 12, 2023.

- Francisco Javier Trigueros-Cano, Departamento de Didáctica de las Ciencias Matemáticas y Sociales, Facultad de Educación, Campus de Espinardo, 30100 Murcia. Tel.: +34 868887127; E-mail: javiertc@um.es

- José María Álvarez-Martínez-Iglesias., Departamento de Didáctica y Organización Escolar, Facultad de Educación, Campus de Espinardo, 30100 Murcia. Tel.: +34 868887948; E-mail: josemaria.alvarez@um.es

- Jesús Molina-Saorín, Departamento de Didáctica y Organización Escolar, Facultad de Educación, Campus de Espinardo, 30100 Murcia. Tel.: +34 868888039; E-mail: jesusmol@um.es;

- María Victoria Zaragoza-Vidal, Departamento de Didáctica de las Ciencias Matemáticas y Sociales, Facultad de Educación, Campus de Espinardo, 30100 Murcia. E-mail: mariavictoria.zaragoza@um.es

The student as human capital in secondary education: an analysis of the impact of socio-demographic variables on the perception of learning.

Francisco Javier Trigueros-Cano, Universidad de Murcia

José María Álvarez-Martínez-Iglesias, Universidad de Murcia

Jesús Molina-Saorín, Universidad de Murcia

María Victoria Zaragoza-Vidal, Universidad de Murcia

1. Introduction

Historically, if we analyse the great changes and transformations that have taken place in Spanish pedagogy, we should point out that these have been marked -mainly- by the renewal of the different regulations that have followed one another since the well-known Law of Public Instruction (1857), through which the government was able to offer a more stable education than had been known until then, remaining in force for more than a century and thus becoming the longest-running educational legislation in the history of the Spanish nation. In this sense, successively - and up to the present day - numerous and very different educational regulations have been proposed by the Administration, with the aim of being restored and modernised (on occasions) or of incorporating new approaches and being reconstructed (on others). Under these premises, Spanish educational regulations were born which - at all times - have sought to respond to the questions raised by means of the well-known multi-theoretical approaches, developed from the social sciences (Miralles et al., 2014:10; Molina et al., 2016:8) and which, of course, have always included among their functions the provision of a conceptual framework with which to transmit to citizens criteria and standards close to contemporary currents of thought. Evidently, in addition to the influence of the synchronic current of thought, the variability of these regulations has always been accompanied by the changes in government that have taken place and - consequently - as a result of historical evolution, these regulations have mutated following the new model approaches from which social environments have been understood. By virtue of the changes in society, it is possible to shed light on the transformations of the different educational regulations which, having as their starting point (or origin) the well-known Moyano Law (1857), have been - at some point - in force, and which are described below in the evolution of our recent history:

- Law of Public Instruction (Moyano Law of 1857)

- General Law on Education and Financing of Educational Reform (Law 14/1970)

- Organic Law on the General Organisation of the Education System (Law 1/1990)

- Organic Law on Education (Law 2/2006)

- Organic Law for the Improvement of the Quality of Education (Law 8/2013)

- Organic Law for the Modification of the Organic Law on Education (Law 3/2020)

From all of them, it is possible to infer the criticisms or alternatives that - throughout history - have been raised in accordance with the Spanish education system and, in the same way, within them, they not only keep the need for the changes that are proposed with a didactic (or pedagogical) dynamic, but - in turn - they are impregnated with the transformative perspectives that accompany the historical stage in which their development took place. This is because education is transformative and its ideology should always allow for a more advanced society to be achieved through the development of shared knowledge; in other words, better education would bring about an improvement in the quality of life of citizens (Monarca and Fernández, 2020). The perspectives that have been developed in the different legislations mentioned have certainly taken into account in their elaboration the currents of thought of the different movements that - in parallel - have occurred.

Specifically, when reviewing some of the educational movements of the 21st century, it is worth highlighting that approach which postulates a necessary and complete transformation of the system (on a political, cultural, social, dogmatic, etc. level), converting education and that -obsolete- instructional curricular training (which has not yet been relegated exclusively to the memory it may have left of its use in previous centuries) into an alternative education (with a variety of methodologies, scenarios, professionals, regulations, etc.). This social movement has been manifested through the different hegemonic discourses worldwide, which -without a doubt- delocalised the responsibility of teachers to the mercantilist political activity and globalising processes that maintain that education must teach (or prepare) only with the obligation that students can respond to the needs of the market (Bejar, 2018:4; Giulano, 2020:6). In this sense, and recognising the co-responsibility for the adequate pedagogical development of students, the well-known social movement stands out, which places its priority focus of observation on awareness and on the important role that the following groups play in the development of education:

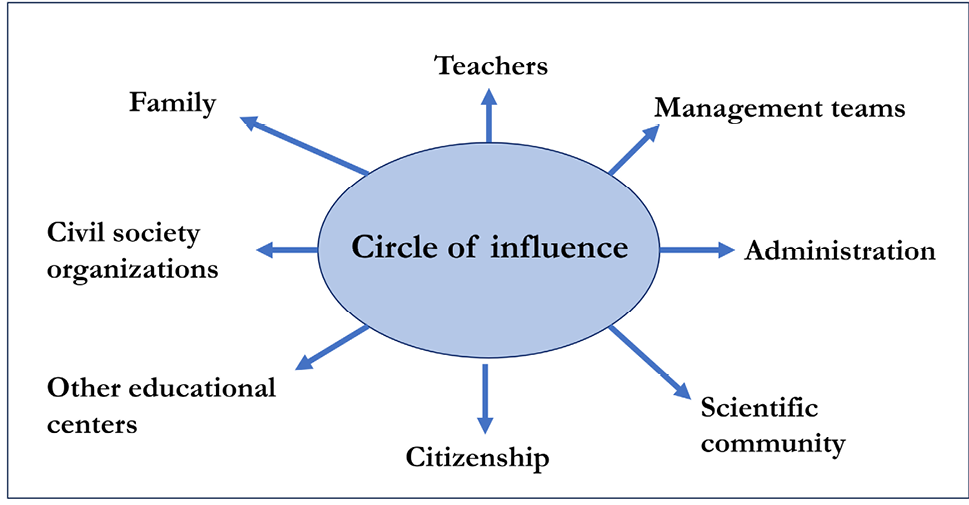

Figure 1. Circle of influence graph for educational progress.

Source: Own elaboration through the analysis of specialised literature -Arguedas and Jimena, (2008); Mejía, (2011).

As can be seen in the previous image (Figure 1), there are certain collectivities through which, by acting as elements of this circle of influence for educational improvement, their functions act directly (or indirectly) on educational development. In this sense, both teachers and management teams and the group of specialist professionals who carry out their work in schools, on numerous adverse occasions (economic crises, political conflicts, social transformations...) have been disregarded in such a way that it would seem that their performance has been subordinated -exclusively- to the economic situation of the moment, or to what the Administration has been requesting of them and which -therefore- has been obligatory, the latter serving as an exemption from any responsibility and justification of their teaching work. However, the inadequate attention to diversity, the high rates of early school dropout, their lack of knowledge of the regulations and the lack of motivation to continue with lifelong learning (Folch and Duran, 2017:11; Lozada, 2017:9), among others, are determining that their performance can (and should) take new paths, deploying new strategies that cause this modification and, therefore, the renewal of educational scenarios. Moreover, as shown in the image above (Figure 1), all these education professionals -together with families- are positioned as the first key actors in the educational processes of adolescents; more specifically, the role played by families is fundamental in establishing -necessarily- a family-school relationship (Fariña, 2009; García, Martínez, et al., 2019:8) which -in addition- in recent decades has been hailed by researchers as one of the spheres in charge of the emancipatory processes for the educational development of their children.

Likewise (and continuing with the description in Figure 1), the Administration (by means of this political-pedagogical function) plays a determining role in the development of minors, not only through the development of regulations that - in an unavoidable way - must be complied with, but also through the revision of outdated legislation that still maintains a mismatch between outdated and current principles, creating confusion both among the legislators themselves (and this is confirmed by the analysis of the regulations - Álvarez, Díaz and Molina, 2020:7) but also, of course, in the development of teachers’ professional practice. Therefore, there is a need for regulations that set out a new approach to schools and students regarding their mandatory participation in the development of their learning, towards the transformation of the organisation and teaching methodologies through new ways of structuring the teaching-learning processes, with a focus on a school where teachers are able to maximise the capabilities of each of their students, thus favouring the exercise of the right to quality education that all children have. And precisely this existing connection between the elements highlighted in the circle of influence happens -in large part- because the scientific community acts as that nexus that asserts (through the countless research carried out) that education and -consequently- the school as an entity that develops it, must provide children with possibilities for them to be creators of their learning and recreators of these by virtue of the transfer of what they have learnt to the world around them (Molina 2017:145); Canelles and Lladós, 2017:12); all of this, so that they can give the greatest meaning to the knowledge they achieve.

Likewise, citizens as a whole play a decisive role in the development of children’s right to education. Culture and, specifically, social experiences are key elements in the exercise of education, since it is not the same for a child to learn in Spain as it is for a child to learn in Turkey (for example). In this sense, culture sets patterns of behaviour that -year after year- become ingrained in the values of students; in this way, what happens is that although the right to quality education is a recognised and legitimised right to be observed worldwide, norms, popular beliefs, social aspects, the country’s experiences (and a long etcetera), converge in a reality that is different for each nation. And under these considerations, it is worth mentioning that Spain follows an educational model that favours -exclusively- those who adapt to the norms, to those stereotyped patterns that lack scientific value and that promote a homogeneous type of student body, unconcerned that they build their own knowledge, since all they have learnt is directed and rigid learning for the performance of certain tasks that - generally - converge in the desire to improve the economic development of the country at the mercy of the training of docile and meek (future) workers. What happens, then, is that, historically, in Spain, the aspirations of all those students who have not been able to follow this old and limited vision of education have been curtailed (Rodríguez, 2013:13).

On the other hand, in parallel with what has been said about the social aspects that are developed in each country, independently - and on numerous occasions - the creation of organisations is carried out (by civil society) that aim to value the rights of all citizens (De Haro, 2010:4; Pagès, J. 2009:8). Under this vision, it is essential to recognise the influence that these organisations exert on educational processes, either through the transformation achieved in the recognition of the right to education (on occasions), or by virtue of the facilitation of solidarity actions in favour of safeguarding this right (on others). In the same way, the figure represented by the group of educational centres is also fundamental to the teaching process, as each of the centres should be able to broaden its vision, without condemning itself to that perspective through which it works in isolation and autonomy without harmony and communion between one and the others. Of course, adopting a collaborative position projects (teachers who take this path) towards that model of teaching in which knowledge can be shared and this - most certainly - disintegrates any hint of competitiveness, a fact that can also be accentuated by the constant assessment tests to which they must respond and with which they are evaluated both nationally and internationally, leading them to believe that in education there are schools that are winners and others that are losers.

Ultimately, the circle of influence outlined above (see Figure 1) is intended to reveal that this is linked to the fact that some schools are winners and others are losers. Figure 1), is linked to this search for new scenarios through which teachers have the obligation to carry out their professional practice by distancing themselves from classical pedagogy or, in other words, by detaching themselves from mercantilist approaches, from teaching practices based on the idea that equality means giving everyone the same thing (without remembering that each child has his or her own educational needs) and which - in addition - do not consider that for each of these children’s educational needs (their own) are as special as those of the rest (Álvarez et al., 2021:7). Similarly, they must also reflect on whether their methodologies continue (or not) to perpetuate an outdated professional practice that does not address the real needs of children, and - if so - become aware of the bad work that is being done when all students are assessed according to a standardised test that, in all scenarios, does not take into account all students, as in the case of all students, does not consider all students, nor does it reflect their true potential and that, certainly, the only thing that is confirmed with these evaluation processes is that the low capacities of a minority (on the one hand) as well as the desires and needs of an immense majority (on the other) are being disregarded, obtaining as a final result the demotivation (or disengagement -Bernárdez, 2019: 8-) of adolescents with respect to their own educational processes, literally translating into those high dropout rates suffered by Spanish education (Bayón, 2019:14).

Logically, the social movement we have been talking about emphasises public educational policies - mentioned above -, which has as a priority focus of attention the discussions inherent in the opposing theses presented by some regulations (from a certain period of time) compared to others (approved only a few years later). This certainly happens with every political change, and assuming that these changes are in line with the ideals of the population they represent (through suffrage), it is absolutely necessary for public policies to move away from this economic perversion and (whether it is the LOMCE, the LOMLOE or the regulations that transcend them), they have the duty to value - among others - two fundamental aspects for education: intrapersonal and also interpersonal development (Malpica and Dugarte, 2018:15; Coral, Fabian, et al. , 2019:6). Intrapersonal value will allow students to know themselves, be aware of their capabilities, know their real needs, and appreciate their aptitudes and attitudes, among other aspects. In the case of the development of interpersonal value, it will favour interaction between children and cooperation, in both cases enhancing (in both cases) the critical thinking that is so necessary to actively develop and prosper in the society in which they grow up.

2. Methodology

2.1 Objectives

The aim of this research is to find out the influence that the socio-demographic variables gender, syllabus, level of studies of the families, as well as the repetition of the course have on the perception of the learning process and its transfer in the subject Social Sciences, Geography and History through the application of a scale called EPECOCISO. Two main objectives were proposed to achieve this aim:

1. To identify the socio-demographic variables that condition the perception of the acquisition of competences in the subject of Geography and History.

2. To find out the socio-demographic variables that condition the transfer of what has been learnt in Social Sciences to a real situation.

2.2 Design

For this research, a quantitative methodological design has been followed, more specifically, it is a descriptive study. Firstly, a Likert-type scale called Evaluation of Perception of Social Science Competences (EPECOCISO) was developed. This instrument is composed of socio-demographic questions and questions about the students’ perception of the teaching and learning process in the subject of Social Sciences, Geography and History. Once the scale had been applied, an exploratory factor analysis of the data was carried out, from which it was possible to extract seven factors. Once the factors had been established, we selected factors F2 and F6 (Perception of competences in terms of what has been learned and Perception of the transfer of what has been learned to a real situation).

Table 1. Statistics of the subscales

|

Escale |

N |

Average |

Typical des. |

|

F2: Perception of competences in terms of what has been learned |

1422 |

3.5080 |

,77057 |

|

F6: Perception of transferability of what has been learned to a real situation |

1422 |

3.6309 |

,92828 |

|

N valid |

1422 |

Subsequently, a correlation matrix of both factors was carried out to look for relationships between their items. Next, the non-parametric Kruskal Wallis test was performed to compare two or more groups. Finally, and whenever the previous tests showed a significant correlation, a post-hoc test was performed.

2.3 Sample

The sample of this study is composed of 1422 students in the 4th year of compulsory secondary education, aged between 15 and 18 years old, from a total of 18 secondary schools in the Region of Murcia. The sampling used was purposive, with a gender balance, i.e. the group was practically equal (51 % male; 49 % female). In the same way, it can be stated that the sample has a very high level of confidence -Bernárdez 2019- (over 95 %, according to the STATS analysis) -Vallejo 2008:12- and a maximum error of 0.7 % (according to the results of the STATS analysis).

2.4 Instrument

The data collection process was marked by the use of an instrument (of original design) consisting of a scale addressed to students (EPECOCISO). As far as this scale is concerned, it should be noted that the items of this instrument were developed in two ways: firstly, an exhaustive documentary analysis was carried out, taking evaluation in the area of social sciences didactics as the core of gravitation, as shown in the design of the theoretical framework. Secondly, a process of consultation has been followed through experts of recognised experience in the field of knowledge of this study, and from secondary schools or higher education centres. At all times, the aim was to evaluate the relevance of the questions designed, the degree of accuracy in the dimensions, as well as the semantic adequacy and comprehension in the wording of each item. As a whole, the panel of judges consisted of nine professionals with expertise in subjects related to the content or nature of the research itself (evaluation, social perception and research methodology). In order to retain an item, the criterion of concordance equal to or greater than 75% of the judges was used. As a result of the outcome of this process, of the 52 initial items (after discarding 8), 44 were retained precisely because they were those that best described and delimited the students’ perception of the competences. Likewise, once the grammatical and content suggestions made by the experts had been taken into account, the 44 final indicators were sifted through a more refined process.

With regard to this instrument, it can be stated that it has good psychometric properties, yielding data that show the different significant relationships between the variables influencing the perception of the level of development of competences according to what has been learned in Geography and History, given that we are dealing with an instrument with a high reliability, with the α coefficient adopting a value of 0.914. Specifically, it is a Likert-type scale in which the students had to choose - from among six options - the one with which they most identified (1= totally disagree; 2= disagree; 3= neither agree nor disagree; 4= quite agree; 5= totally agree, and NS= don’t know).

As can be imagined for this type of study, before starting the data collection, permission was requested from the responsible academic authorities; once permission was granted, the instruments were applied directly, with the research team going directly to each of the classrooms in the participating centres where -in real time- the questionnaires were distributed to the students for their response (lasting approximately 20 minutes).

3. Results and discussion

This section presents the results obtained after analysing the information from the EPECOCISO scale. Specifically, this section is divided into two parts, each corresponding to one of the factors, as well as to the specific objectives proposed in the methodology of the study.

Factor 2: Pupils’ perception of basic competences as a function of what they have learned in the area of Social Sciences, Geography and History.

In order to verify the relationship between socio-demographic variables and pupils’ perception of what they have learnt in Social Sciences, Geography and History, the following socio-demographic variables were analysed: the educational programme followed by the pupils surveyed (Compensatory, Diversification, Integration, Advanced and bilingual), the parents’ level of studies and gender.

In this sense, no significant differences are obtained in the curriculum or in the parents’ level of studies, so it can be affirmed that the pupils’ perception of what they have learnt in class is not linked to these variables. However, significant differences are observed in relation to gender. Specifically, the significance increases when they are questioned about the usefulness of the learning acquired, for example, to use language to express my emotions, experiences and opinions, so that others can understand me; to consider that the training received in Social Sciences helps me to realise the importance of competence in knowledge and interaction with the physical world and their commitment to the surrounding environment and society; for the development of citizenship and participation at a social level (to take part in elections, create associations, etc. ); to express oneself, to communicate, and to perceive and understand different realities and productions in the world of art and culture; as well as to be aware of what one knows and what one needs to learn in order to construct one’s own knowledge.

For all these questions that make up factor F2, it is the female students who perceive the greatest perception of learning in the subject of Social Sciences, Geography and History, so it can be affirmed that, according to the perception of the respondents, it is the female students who learn more quickly and efficiently, and above all, they are aware of the whole teaching and learning process carried out.

Factor 6: Students’ perception of the transfer of what they have learnt in Social Sciences to a real-life situation

As in the previous factor, in order to verify the relationship between the socio-demographic variables and the perception - in this case - of the pupils’ perception of the transfer of what they have learnt in Social Sciences to a real situation, we first analysed these socio-demographic variables, which include: the educational programme studied by the pupils surveyed (Compensatory, Diversification, Integration, Advanced and bilingual), the parents’ level of studies and gender.

In this case, we do find differences in relation to the programmes in which the pupils are enrolled. Specifically, between the Bilingual and Diversification programmes, it can be observed that there are significant differences between the answers given by the students on the Bilingual-English programme and those on the Diversification programme (p-value = .005) when they are asked about the usefulness of what they have learnt in class and its application to their daily lives. In this case, it is the students in the Bilingual programme who perceive a greater transfer of what they have learnt in the subject of Social Sciences, Geography and History than those enrolled in one of the curricular diversification programmes.

Table 2: Comparisons of items by sex

|

Question |

U Mann-Whitney |

p-value |

Sig. |

|

P1 |

106463.0 |

0.0043 |

Y |

|

P2 |

94395.5 |

0.6172 |

N |

|

P3 |

104154.5 |

0.0273 |

Y |

|

P4 |

94227.0 |

0.5858 |

N |

|

P5 |

106799.5 |

0.0037 |

Y |

|

P6 |

111031.5 |

0.0000 |

Y |

|

P7 |

108098.0 |

0.0010 |

Y |

|

P8 |

99731.5 |

0.3311 |

N |

In the case of parents, we found that there are significant differences according to the educational level of the mother in the answers obtained when the students were asked about the recognition and appreciation of the cultural and historical heritage of the Region of Murcia (archaeological remains, museums, etc.), as well as to relate what they have learnt to other knowledge they have and which can serve as a basis for learning new content or for learning it in another way.

Table 3: Comparisons of items according to Educational Programme

|

Question |

K Kruskal-Wallis |

p-value |

Sig. |

|

P25 |

12.83 |

0.12 |

N |

|

P26 |

24.84 |

0.00 |

Y |

|

P27 |

5.51 |

0.70 |

N |

|

P28 |

14.46 |

0.07 |

N |

|

P29 |

10.54 |

0.23 |

N |

|

P30 |

4.88 |

0.77 |

N |

|

P31 |

9.54 |

0.30 |

N |

|

P32 |

13.27 |

0.10 |

N |

As can be seen, there are significant differences between the answers given by students whose mothers have a secondary/high school education and students whose mothers have a primary education (p-value = .021) and students whose mothers have no education (p-value = .037). There are also significant differences between the answers given by students whose mothers have a higher/university education and students whose mothers have a primary education (p-value = .026). According to the results obtained, the students perceive a better transfer of the learning acquired in this subject to the extent to which the mother’s studies are of a higher level. This question highlights the sensitivity of mothers to their children’s education, so that - on most occasions - by spending more time with her, to the extent that importance is given to learning and transfer, even with the example of the parents themselves, the pupils will see it in the same way.

Table 4: Comparisons of items by mother’s level of education

|

Question |

K Kruskal-Wallis |

p-value |

Sig. |

|

P25 |

3.89 |

0.27 |

N |

|

P26 |

4.34 |

0.23 |

N |

|

P27 |

5.66 |

0.13 |

N |

|

P28 |

3.65 |

0.30 |

N |

|

P29 |

3.59 |

0.31 |

N |

|

P30 |

8.14 |

0.04 |

Y |

|

P31 |

12.71 |

0.01 |

Y |

|

P32 |

0.87 |

0.83 |

N |

It is also clear that the fact that a pupil repeats a year conditions the perception he/she has of what he/she has learnt and how useful it is for application in everyday situations. In this sense, the greatest degree of significance is found when the pupil is questioned about The search for and use of information through digital media and the knowledge acquired in the subject of Social Studies about history, culture, art or geography, and its usefulness in obtaining information and data to be used in other areas of their lives; the evolution in the attitude of respect and help for others, the acceptance and understanding towards people who have ideas different from their own (or who have a different culture or religion) which the Social Studies class provides them with. Geography and History, as well as in valuing the cultural and historical heritage of the Region of Murcia (archaeological remains, museums, etc.). In this sense, it can be affirmed that repeating pupils have greater difficulty in transferring what they have learnt in this subject, highlighting the benefits that repeating the course can have and, in particular, the danger that not carrying out the necessary methodological adaptations which, according to regulations, must be contemplated can represent in the pupils’ education.

Table 5: Comparisons of items by repeater and non-repeaters

|

Question |

U Mann-Whitney |

p-valur |

Sig. |

|

P25 |

78449.0 |

0.8954 |

N |

|

P26 |

81342.5 |

0.3267 |

N |

|

P27 |

75232.0 |

0.4123 |

N |

|

P28 |

69880.0 |

0.0160 |

Y |

|

P29 |

85431.5 |

0.0293 |

Y |

|

P30 |

72251.0 |

0.0882 |

N |

|

P31 |

68266.0 |

0.0037 |

Y |

|

P32 |

77934.0 |

0.9839 |

N |

Finally, significant differences are also found in relation to the sex of the students when they are questioned about the relationship they acquire with those they had previously, and also when they are asked about the way they assimilate new concepts and put them into practice, and more specifically when they are asked about the value they attach to cultural and historical heritage. It is the female pupils who perceive it to be easier to assimilate the above questions. This is probably due to the level of maturity of the pupils, so that no clear pattern could be established. However, the results of this analysis highlight the close relationship between the gender of the students and the mother’s level of education, as these students who perceive a higher level of transferability in their learning may be the mothers of the future. Of course, taking these issues into account, proposals for improvement and the necessary reforms can be carried out in order to achieve the much-desired educational quality proposed by the European Union in the PISA assessment tests (Order ECD/65/2015:221; OECD 2018:19; OECD 2020:55).

Table 6: Comparisons of items by sex

|

Question |

U Mann-Whitney |

p-value |

Sig. |

|

P25 |

113271.0 |

0.7654 |

N |

|

P26 |

108420.0 |

0.3740 |

N |

|

P27 |

116528.0 |

0.2707 |

N |

|

P28 |

116866.5 |

0.2351 |

N |

|

P29 |

108297.0 |

0.3586 |

N |

|

P30 |

121908.0 |

0.0151 |

Y |

|

P31 |

131384.5 |

0.0000 |

Y |

|

P32 |

112091.5 |

0.9932 |

N |

4. Conclusion

Broadly speaking, it could be said that - in recent decades - education in Spain has undergone important reforms (learning standards, teaching by competences, theories on inclusion, etc.), which have managed to transmute that vision - until now - static or inflexible and with few expectations for the improvement of teaching and learning processes in our country (Gortázar and Moreno, 2017:4; Monarca and Fernández, 2020:8). In short, education in Spain (as in the rest of the world) has mutated to the same extent as social environments and the needs that (at least apparently) citizens have been showing, although -certainly- these needs have been blurred since the development of regulations has not served to give due compliance with the obligatory nature (or the primary purpose) of the exercise of children’s right to education (Vidal, 2017:3; Gómez et al 2016:15; Gómez et al 2016:13). Learning and ensuring this principle of individualisation is as important as it is necessary, insofar as it is known to open and welcome all students by offering them the possibility of learning, always understanding and comprehending that each student is different and, therefore, individually have their own claims, dreams or desires regarding their learning. Through this principle of individualisation, the actors involved in this circle of influence (shown in Figure 1) must work towards the development of teaching that also facilitates the acquisition of knowledge, and that students are able to put this knowledge into practice in their everyday realities and personal experiences; In other words, taking as a starting point that each child is different and so is the reality they may be living in their socio-familial context, no child is certainly prepared to reach what is normatively defined as minimum requirements (or learning standards). In this way, education - in our country - has been relegated exclusively to what the student knows - or does not know - about each of the subjects (Álvarez, Díaz and Molina, 2021:6) or also what he or she is capable of doing (or not) with respect to the activities that teachers propose in the classroom in order to achieve this learning. Apparently, the formula that educational centres -together with the Administration- have developed is simple; a child arrives in the classroom full of dreams and illusions to achieve and, in it, he/she finds activities in which he/she should supposedly be recognised and be able to perform to perfection, as stated in the Organic Law for the Improvement of Educational Quality (LOMCE -law 8/2013:50-). However, the child feels that he/she cannot do them (moreover, he/she does not have the skills to be able to develop them), becomes frustrated, and it is - at that precise moment - when the child acquires the only learning that he/she will carry in his/her backpack that day: that he/she cannot! That he/she is not capable of doing it! That he/she does not know, nor will know! That his/her teacher is not helping him/her!

In this sense, the changes proposed include the necessary renewal of the training received by teacher training students during their transition to higher education or, for example, the desire - even expressed by the educational administration - to modify (completely) the outdated methodologies still used in our country’s schools (from traditional pedagogy to universal learning design - Álvarez, Díaz and Molina, 2021:9). Or also through (apparently simple) changes that make it possible for didactic tasks in the classroom to be transcendental and motivating for students, thus completely replacing standardised activities and assessments that do not represent the vast majority of students and that -without any scientific basis- still today represent a high cost for all those children (and their families) who wish to be able to read a pass in their grades, not only does the understanding remain that a fail means that the child does not know, but that - for sure - as long as the methods used are the same, the child will hardly understand how he or she learns.

And as long as the formula remains the same, without making the changes that even the regulations themselves are already calling for, the result will continue to be disastrous for children and their education. Evidently, the educational history of our country is extensive and cannot be defined by a single path, since - as has been indicated above - it has evolved in line with the different social movements and, synchronically, with the various regulations approved. After this brief overview of the current Spanish school and the policies that regulate it, it is worth mentioning that with the approval of the Organic Law on Education (LOE, 2006:45), one of the current legislative modifications took place, incorporating learning by competences into the educational corpus (Álvarez et al., 2021:6). This new approach aims to give value to a more scientific vision than the unidirectional transmission of knowledge (from which the teacher teaches through books, with master classes, without knowing -with certainty, at least until the evaluation- if what is being radiated is learning achieved by all), and from which learning is transferred in a solid way, facilitating conceptual and practical teaching through the promotion of motivation, values, attitudes and other social components with which to achieve a joint action of all the elements of the circle of influence shown in the previous image (Figure 1). In this sense, competences are defined as that knowledge that is obtained through practice (or active participation) that can be developed in formal, non-formal and informal educational contexts Seixas, P., & Peck, C. 2004:5). With regard to this perspective, the proposal made in the regulations is none other than to work on competences - in an integrated manner - through the curricular contents, with the desire that the proposed contents contribute to the achievement of the didactic objectives and, in general, to the adequate promotion of all students in their different educational stages. And the fact is that teaching by competences - without going into whether they are favourable (or not) for teachers and students - as well as being a firm commitment by Spain to be part of the action protocols that are being carried out in Europe in the field of education, aims to guarantee academic excellence by means of a know-how that would be framed in the three scenarios in which, a priori, students develop: the school, the family and the educational setting. Furthermore, its purpose is to ensure that all students can achieve a quality education and -of course- that through it they achieve the maximum development of their capacities (together with this principle of individualisation) and, at the same time, it is possible to awaken in students a critical and participative attitude with which they are able to acquire new knowledge, promote new ways of learning, promote efficiency in the implementation of didactic activities (by professionals) and, definitively, promote the lifelong learning of both teachers and students -Leibowicz, 2020:6-.

In this way, competences are presented to contribute to this new perspective that places the priority focus of attention on the comprehensive development of the student, downplaying the importance of how much students will learn and under this desire to favour knowledge about their real needs, their expectations, life experiences and desires, among many other elements (Domínguez, J. 2015:3; Gómez et al., 2020:12; Gómez 2017:15). In short, this recent approach to teaching by competences represents a new challenge for both the administration and teachers, since its implementation means redefining a large part of the traditional educational structure. Furthermore, it should be borne in mind that the incorporation of changes in regulations may cause conflicts at different levels such as - for example - in interpretation and implementation by teachers, as well as the absence of previous models that allow us to know how to carry out the appropriate work of all those involved in this circle of influence that was represented above.

Biblioography

ÁLVAREZ, J.M; DÍAZ, Y; MOLINA, J. (2021) El Código Cuomo. Las fábulas de María: una niña a la que no le gustaba la escuela. Dykinson

ÁLVAREZ, J. M.; MOLINA, J.; MIRALLES, P.; TRIGUEROS, F. J. (2021) Perception of 4th year compulsory secondary education students on key competences: towards a transfer of knowledge. Sustainability, 13(4).

ÁLVAREZ, J.M.; MIRALLES, P.; MOLINA, J; TRIGUEROS, F.J. (2021) Perception of secondary education students on the acquisition of social sciences competences. Social Sciences, 10(4).

ÁLVAREZ, J. M.; TRIGUEROS, F. J.; MIRALLES, P; Y MOLINA, J. (٢٠٢٠). Assessment by Competences in Social Sciences: Secondary Students Perception Based on the EPECOCISO Scale. Sustainability, 12(23), 1-15. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310056

ARGUEDAS, I., & JIMÉNEZ, F. I. (2008). Factores que promueven la permanencia de estudiantes en la educación secundaria. Actualidades Investigativas en Educación, 7 (3).

BAYÓN-CALVO, S. (2019). Una radiografía del abandono escolar temprano en España: Algunas claves para la política educativa en los inicios del siglo XXI. Revista Complutense de Educación, 30(1), 35.

BEJAR, L. H. (2018). Humanizando la educación del mercantilismo vigente. Compas.

BERNÁRDEZ-GÓMEZ, A. (2019). Formación inicial del profesorado, el papel de los tutores de prácticas. Revista Educactio Siglo XXI, 39 (2), 419-442.

CANELLES, J. Y LLADÓS, L. (2017) La escuela tradicional y la escuela transformadora. Aula de innovación educativa. 267, 15-19.

DE HARO, J. J. (2010). Redes sociales en educación. Educar para la comunicación y la cooperación social, 27, 203-216.

DOMÍNGUEZ, J. (2015). Pensamiento histórico y evaluación de competencias. [Historical thinking and competence assessment] Graó.

FARIÑA, J. A. S. (2009). Evolución de la relación familia-escuela. Tendencias pedagógicas, (14), 251-267.

GARCÍA, P. Á. C., MARTÍNEZ, M. P. J., & TORTAJADA, E. G. (2019). Aprender a emprender bajo el binomio familia-escuela. Revista electrónica interuniversitaria de formación del profesorado, 22(3), 139-154.

GÓMEZ, C.J. Y MIRALLES, P. (2013). Los contenidos de ciencias sociales y las capacidades cognitivas en los exámenes de tercer ciclo de Educación Primaria ¿Una evaluación en competencias? Revista Complutense de Educación, 24, 91-121.

GÓMEZ, C. J. Y MIRALLES, P. (2016). Historical skills in compulsory education: assessment, inquiry based strategies and students’ argumentation. NAER. New Approaches in Educational Research, 2 (9), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.7821/naer.2016.7.172

GÓMEZ, C. J., Y RODRÍGUEZ, R. A. (2017). La enseñanza de la historia y el uso de libros de texto ante los retos del siglo XXI. Entrevista a Rafael Valls Montés. [The teaching of history and the use of textbooks in the face of the challenges of the 21st century] Historia y Memoria de la Educación, 6, 363-380. https://doi.org/10.5944/hme.6.2017.18746

GÓMEZ, C. J., SOLÉ, G., MIRALLES, P., & SÁNCHEZ, R. (2020). Analysis of cognitive skills in History textbook (Spain-England-Portugal). Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.521115

GORTÁZAR, L., & MORENO, J. M. (2017). Costes y consecuencias de no alcanzar un pacto educativo en España. Revista Educación, política y sociedad, 2(22), 9-37. Recuperado de: https://revistas.uam.es/reps/article/view/12266

INE, INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTADÍSTICA (2009). Encuesta de Población Activa. Diseño de la Encuesta y Evaluación de la Calidad de los Datos. Madrid: Instituto Nacional de Estadística. http://www.ine.es/docutrab/epa05_disenc/epa05_disenc.pdf

LEIBOWICZ, J. (2000). Ante el imperativo del aprendizaje permanente, estrategias de formación continua (Vol. 9). Oficina Internacional del Trabajo/CINTERFOR.

LOE (2006). Ley Orgánica 2/2006, de 3 de mayo, de Educación. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 106, de 4 de mayo de 2006.

LOMCE (2013). Ley Orgánica 8/2013, de 9 de diciembre, para la mejora de la calidad educativa (LOMCE). Boletín Oficial del Estado, 295, de 10 de diciembre de 2013.

LOMLOE (2020). Ley Orgánica 3/2020, de 29 de diciembre, por la que se modifica la Ley Orgánica 2/2006, de 3 de mayo, de Educación. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 340, de 30 de diciembre de 2020.

LOZADA, J. C. P. (2017). Formación permanente de los docentes como referente de la calidad educativa. Revista Scientific, 2(5), 125-139.

MALPICA, A., & DUGARTE, A. (2018). La dinámica de grupos, un encuentro intra e interpersonal en las relaciones humanas. Revista Arjé, 12(22), 523-528.

MIRALLES, P., MOLINA, J. Y TRIGUEROS, F. J. (2016). Diálogos de evaluación en la Educación Secundaria Obligatoria: escenarios, protagonistas y estado actual de la investigación en ciencias sociales, geografía e historia. En Sentidos e desafios da avaliação educacional (pp. 105-138). Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná.

MIRALLES, P., GÓMEZ, C. J., & SÁNCHEZ, R. (2014). Dime qué preguntas y te diré qué evalúas y enseñas.[ Tell me what you ask and I will tell you what you evaluate and teach.] Aula Abierta, 42, 83-89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aula.2014.05.002

MOLINA, J. (2017). La discapacidad empieza en tu mirada: las situaciones de discriminación por motivo de diversidad funcional: escenario jurídico, social y educativo. Delta Publicaciones.

MOLINA, J., MIRALLES, P. Y TRIGUEROS, F. J. (2014). La evaluación en ciencias sociales, Geografía e Historia: percepción del alumnado tras la aplicación de la escala EPEGEHI-1. Educación XXI, 17 (2), 289-312. https://doi.org/10.5944/educxx1.17.2.1149

MONARCA, H., & FERNÁNDEZ GONZÁLEZ, N. (2020). Reconfiguración de los sentidos sobre la educación en España a partir de la nueva ley de educación (LOMCE). En Monarca, H. Evaluaciones Externas: Mecanismos para la configuración de representaciones y prácticas en educación. UAM.

OECD (2018) The future of educations and Skill. Publishing: Paris, France, from https//www.oecd.org/education/2030/E2030%position%20paper%20

OECD (2020) OECD Skills Strategy 2019. Skills for a Better Future. Madrid: OECD Publishing and Fundación Santillana. https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/e3527cfb-es

ORDEN ECD/65/2015, de 21 de enero, por la que se describen las relaciones entre las competencias, los contenidos y los criterios de evaluación de la educación primaria, la educación secundaria obligatoria y el bachillerato. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 25, pp. 1-18.

PAGÈS, J. (2009). El desarrollo del pensamiento histórico como requisito para la formación democrática de la ciudadanía. Reseñas de Enseñanza de la Historia, 7, 69-91. https://pagines.uab.cat/joan_pages/sites/pagines.uab.cat.joan_pages/files/2009_Pages_Rese%c3%b1as_7.pdf

RECOMENDACIÓN 2006/962/CE del Parlamento Europeo y del Consejo, de 18 de diciembre de 2006, sobre las competencias clave para el aprendizaje permanente. Diario Oficial de la Unión Europea, L 394/10, de 30 de diciembre de 2006.https://eurlex.europa.eu/legalcontent/ES/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32006H0962

RODRÍGUEZ CAVAZOS, J. (2013). Una mirada a la pedagogía tradicional y humanista. Presencia universitaria, 3(5), 36-45.

SEIXAS, P., & PECK, C. (2004). Teaching historical thinking. En A. Sears & I. Wright, Challenges and prospects for Canadian social studies (pp. 109-117). Pacific Educational Press.

TRIGUEROS, FJ.; MOLINA, J.;ÁLVAREZ, J M. (2017). La enseñanza de la historia y el desarrollo de competencias sociales y cívicas. [History teaching and the development of social and civic skills]Clío. History and History Teaching, 43, 1-10

VALLEJO, M. (2008). Estadística aplicada a las ciencias sociales. Universidad Pontificia Comillas.

VIDAL-ABARCA, E. (2017). El contenido y la evaluación de los aprendizajes. En E. Vidal Abarca, R. García, & F. Pérez (Eds.), Aprendizaje y desarrollo de la personalidad (pp. 99-138). [Learning content and assessment ]Alianza.

VIDAL PRADO, C. (2017). El derecho a la educación en España. Marcial Pons, Ediciones Jurídicas y Sociales.