AREAS. Revista Internacional de Ciencias Sociales, 43/2022

Social and environmental effects of mining in Southern Europe (pp. 53-65)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.6018/areas.481771

Safety, Exploitation of Labour and Industrial Relations in an Italian mine in the 20th century

Adolfo Turbanti

Istituto Storico Grossetano della Resistenza e dell’Età Contemporanea (ISGREC)

Abstract

Italian mine activity has never been comparable to that in the most important industrialised countries. The lack of minerals has always been one of the greatest problems hindering industrial development. However, in the first half of the twentieth century and until the ‘70s, mineral extraction was a significant part of the national economy, employing many thousands of workers. More specifically, at first copper mines, later mainly pyrite ones, represented the basis for the development of Montecatini, the big Italian chemical monopoly. The Ribolla lignite mine, in the southern part of Tuscany, was also owned by the Montecatini Company. The mine had a remarkable development during the Second World War and 1,200 miners still worked there in May 1954. The 1954, May 4th disaster in that mine is one of the worst mine accidents ever happened in Italy. The firedamp explosion caused 43 deaths and was matter of huge controversy and debate among trade unions and left political parties on the one hand and the Montecatini Company on the other. Before the disaster, the Miners’ Union had reported serious safety problems with regard to working methods. A deeper insight into the event began to emerge only many years later. In particular, studies based on part of the documents made available from the trial against Montecatini were published in 2005. After the disaster, Montecatini was forced to adopt safety measures and to invest money to improve the working conditions, particularly ventilation in the tunnels. However, the mine’s life had come to an end and some years later it was closed. My study will show how the mining company, trade unions, political parties and local governments acted after the mining disaster. For example, how industrial relations changed in the still open mines. In a social environment dominated by the Left, the Montecatini had to abandon the authoritarian behaviour, which was probably derived from the fascist era. The Left, on the other hand, had to renounce the most radical elements of its programmes, such as the nationalization of the mines.

Keywords

Mining disaster; mining community; piecework; mining method; miners’ movement

JEL codes: J28, J51, N54, N94

SEGURIDAD, EXPLOTACIÓN DEL TRABAJO Y RELACIONES INDUSTRIALES EN UNA MINA ITALIANA EN EL SIGLO XX

Resumen

La actividad minera italiana nunca ha sido comparable a la de los países industrializados más importantes. La falta de minerales siempre ha sido uno de los mayores problemas que han obtaculizado el desarrollo industrial. Sin embargo, en la primera mitad del siglo XX y hasta los años 70, la extracción de minerales fue una parte importante de la economía nacional, empleando a miles de trabajadores. Más específicamente, al principio las minas de cobre, luego principalmente las de pirita, representaron la base para el desarrollo de Montecatini, el gran monopolio químico italiano. La mina de lignito Ribolla, en la parte sur de la Toscana, también era propiedad de la Compañía Montecatini. La mina tuvo un desarrollo notable durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial y en mayo de 1954 todavía trabajaban 1.200 mineros. El desastre del 4 de mayo de 1954 en esa mina es uno de los peores accidentes mineros jamás ocurridos en Italia. La explosión de grisú provocó 43 muertos y fue motivo de gran polémica y debate entre sindicatos y partidos políticos de izquierda, por un lado, y la empresa Montecatini, por otro. Antes del desastre, el Sindicato de Mineros había denunciado serios problemas de seguridad por los métodos de trabajo. Una visión más profunda del evento comenzó a surgir solo muchos años después. En particular, en 2005 se publicaron estudios basados en parte de los documentos disponibles del juicio contra Montecatini. Después del desastre, Montecatini se vio obligado a adoptar medidas de seguridad e invertir dinero para mejorar las condiciones de trabajo, en particular la ventilación de los túneles. Sin embargo, la vida de la mina había llegado a su fin y algunos años después se cerró. Mi estudio mostrará cómo la empresa minera, los sindicatos, los partidos políticos y los gobiernos locales actuaron después del desastre minero. Por ejemplo, cómo cambiaron las relaciones laborales en las minas aún abiertas. En un ambiente social dominado por la izquierda, los Montecatini tuvieron que abandonar el comportamiento autoritario, que probablemente se derivaba de la era fascista. La izquierda, en cambio, tuvo que renunciar a los elementos más radicales de sus programas, como la nacionalización de las minas.

Palabras clave

Desastre minero; comunidad minera; trabajo a destajo; método de minería; movimiento minero

Códigos JEL: J28, J51, N54, N94

Original reception date: May 31, 2021; final version: March 29, 2022.

Adolfo Turbanti. Istituto Storico Grossetano della Resistenza e dell’Età Contemporanea (ISGREC). Via dei Barberi, 61, 58100 Grosseto GR, Italia.

E-mail: aturbanti@gmail.com; ORCID ID: 0000-0002-8097-4192.

Safety, Exploitation of Labour and Industrial Relations in an Italian mine in the 20th century

Adolfo Turbanti

Istituto Storico Grossetano della Resistenza e dell’Età Contemporanea (ISGREC)

1. The mining disaster of Ribolla

Ribolla is the name of a creek that runs along the southern margins of the so called Colline Metallifere, one of the two main mining basins in Maremma1. Lignite had been mined along the creek at least since the mid-19th century, but a more continuous extraction, with its highs and lows, only started in the 1920s, after the mine was acquired by Montecatini, the biggest mining and chemical company in Italy. A new mining village, built near the shafts and named after the creek, came to house a few thousand employees, amongst workers, technicians and managers. The search for the mineral gained momentum, the network of tunnels was expanded and new shafts were dug to a depth of more than 300 metres (approximately 250 metres below sea level).

An account of the disaster of May 4th 1954 can be found in a book published two years later by writers Carlo Cassola and Luciano Bianciardi for an eminent Italian publishing house.2 It is a very passionate, but substantially reliable report and it has been drawn upon over the years for innumerable ceremonies, commemorations and theatrical performances. The explosion took place between 8.35 and 8.45 a.m. in the Camorra pit, shortly after the workers of the first shift had gone underground. 42 miners died immediately, many were injured. The 43rd victim was a miner who, staying in the pit at the time of the accident, survived, but was struck down with a sudden illness a few weeks later: his death too was attributed to the explosion.

The Miners’ Union of CGIL (the Italian General Confederation of Labour) had been voicing concerns over the safety conditions in the mine for months before the accident. The secretary of the internal Commission had been fired for confronting the mine’s Management over them. To many, the disaster looked like a tragedy foretold, of which Montecatini was directly, and clearly, responsible.

As a matter of fact, it was not possible to understand what had actually happened and what the direct cause of the explosion was. Nobody amongst the direct witnesses survived and none of the injured could provide the information necessary for a precise and detailed reconstruction, as they were working in distant tunnels. A month later, the Miners’ Union published a report in which, following on from previously voiced complaints, the violation of mining laws was denounced in both the changes to the mining method and the deficiencies in the ventilation circuit imposed by the management. According to the CGIL, these were the causes of the firedamp explosion. The report also pointed out the authoritarian methods adopted towards the workers, «while it is universally acknowledged that, in a mine context, the most important factor towards safety is for the workers to have self-discipline, in an environment of collaboration between managers, technicians and workers».3 The investigation committee, appointed by the Ministry of Labour, did not dismiss the responsibility of the management of Montecatini, but ruled out the possibility that the disaster was caused by the new mining method, which was, after all, approved by Corpo delle Miniere, the ministerial office tasked with supervising mining activities.4

Two years later, the managers of the mine and the chief engineer of Corpo delle Miniere of Grosseto were brought to trial. The judicial examination ruled out that the explosion had been caused by firedamp and attributed it instead to an excessive concentration of coal dust combined with gases released by fires in the tunnels. The Court of Verona, called to pass judgment on the case in 1958, was presented with an incoherent series of technical reconstructions, while the lawyers for the defense put forward yet another version of the accident. Given the impossibility to establish what the truth of the matter was, the judges abstained from any attribution of guilt and acquitted the accused.5

There was great disappointment in the community of Ribolla and all around the Colline Metallifere. It didn’t seem possible that the death of 43 workers was to be attributed to bad luck, when responsibilities had already been pointed out even before the accident. At the same time, a deep feeling of resentment arose against the workers’ widows, who had accepted a monetary settlement from Montecatini before the trial, thus losing some of the leverage they could have had in court. One after the other, all the families of the dead workers took this same decision. The first ones accepted a direct proposal from Montecatini, often with the mediation of the local priest or Catholic charitable association; the last ones consented to a confidential agreement presented to them by CGIL. The left wing union indeed, after an initial refusal, had accepted to secretly negotiate with the lawyers of Montecatini, in an effort to safeguard those families who had rejected the unilateral settlement proposal. The absence of a plaintiff in the trial paved the way for the judges of Verona to pass the acquittal judgment in the criminal proceeding.

Today, we feel that this tragedy marked a turning point in the history of not only the small village of Ribolla, but of the surrounding area and the whole province, with significant consequences at national level. I will try to briefly present the framework in which these events took place: in particular, I will focus on the social conflict, both internal and external to the mine, and on its political management.

2. Pyrite and lignite: the Montecatini “system”

Mineral extraction has never had a big role in Italian economy. In fact, the scarcity of essential minerals, such as iron and coal, has always been one of the main hindrances to the industrial development in Italy and one of the causes of its reduced dynamism compared to other countries.6 Imports for iron and coal have constantly been two liability items in the balance of trade, and have negatively affected both the first industrial revolution and the economic boom after the Second World War. The same can be said about hydrocarbons, whose internal production has always covered only a fraction of the domestic demand.7 For a long time, however, Italy has held a significant place in the global production of less important minerals, which are nonetheless essential to the supply chain of specific industrial products. That is the case of pyrite and mercury, both produced in the Maremma territory.8

I will not talk about mercury, which was obtained by distillation from cinnabar9 extracted in the mines of Mount Amiata. I will instead touch on pyrite, because it was thanks to its extraction that Montecatini began to build its industrial empire at the beginning of the 20th century, long before its relocation to Milan (1910).10 Montecatini, which was to become one of the major industrial groups in Italy and, for several years, the greatest chemical company in the country, took its first steps in Maremma, one of the most marginal and economically depressed areas of Tuscany11 and, at least until the mid-twentieth century, of the whole nation.12 In this sense, the pyrite mines in Maremma had a crucial role for the national economic history, far beyond the importance of still relevant production. Montecatini was founded in 1888 with the purpose of managing a nearly exhausted copper mine at the southern borders of the province of Pisa, in the municipality of Montecatini Val di Cecina, after which the company was named. The following year Montecatini acquired a more important copper mine, not far from the first one but within the borders of the province of Grosseto. The management, especially the young CEO Guido Donegani, soon realized that the extraction of pyrite, which was found in the area in wider and thicker seams, would be a much more profitable enterprise compared to the extraction of copper.13 Pyrite is a very common iron sulphate (FeS2) and it was at the time, and would have been for many more years, the prime raw material for the production of sulfuric acid (H2SO4): acquiring a monopolistic position in this sector would have meant controlling the entire national chemical industry. Montecatini managed to achieve this position. The extraction of the mineral was carried out in Maremma, while the chemical production was moved elsewhere, with the exception of a single plant in the southern part of the province. Firstly, Montecatini gained a monopolistic position in the production of fertilizers, combining the use of sulphuric acid with phosphorites extracted in open pits in the African deserts. It then expanded its interests to hydrocarbons and plastic materials, a step that would lead to a further growth of its business. The Company also dealt in other minerals extracted in different regions, always striving for a vertical integration of the productive process –i.e. controlling the entire production chain– from the raw materials to the finished or semi-finished product (as was the case with aluminum, obtained from bauxite14). This approach, which we can call the “Montecatini system”, allowed the Company to take on a key role in the development of agriculture, first through a widespread marketing of superphosphates, secondly of nitrogen fertilizers. Montecatini acquired the vast majority of pyrite and other sulfide mines in Maremma, leaving the extraction of other minerals to other companies, as it happened in the nearby Mount Amiata area.

We need to then ask ourselves what the role of lignite, the coal extracted in Ribolla, was within the “Montecatini system”. I am convinced that this is a fundamental question, one that cannot be underestimated if we wish to understand not only the causes, but also, as far as possible, the dynamic of the mine disaster of May 4th 1954 and, above all, its overall significance. We must consider that the extraction of lignite was not strategically important for Montecatini and neither was it part of a vertical integration process. The Company never planned to acquire a monopolistic position in its extraction: the proof of this is the fact that it never showed any will to acquire other companies in the sector. For instance, there was a vast lignite basin in the Upper Valdarno area of Tuscany, already widely exploited by other companies especially for electricity production, but Montecatini never showed any interest in it.15 After all, lignite was a very low-value coal, even if the one found in Ribolla, a compact lignite with a relatively low moisture content, was more refined than other kinds.16 Its nearest destination could have been the steel industry in Piombino, but the production of coke for steel mills required a caloric power that could only be achieved with imported coal.17 It must be concluded that the interest of Montecatini for lignite was mostly a speculative one. The goal, by relying on the economies of scale offered by the proximity of other mines of the Group, could only be to take advantage of favourable phases of the market, when the price of imported coal was too high or the import itself was prevented.

In 1924, Montecatini became the sole owner of the Ribolla mine, after having contributed to its management in different ways for a few years.18 In this way, the Company strengthened its control over all the mining activity of Colline Metallifere; consequently, on the economy of the area itself and in particular on the labor market.

The control over its own manpower wasn’t confined to the workplace, but to everyday life as well. In the mines, the workers represented the lowest grade of a military-like hierarchy and had to observe strict discipline. In the village, the labourers could benefit from social services and community spaces provided by the Company: even their spare time was organized by Montecatini. This represented the social face of the “system”, through which the capitalistic command inside the mine was reflected on the outside life, by means of a paternalistic control. Social relations outside the workplace came to mirror the internal ones and vice versa.

I will not go into detail about this dynamic, but I will highlight that the intentions of Montecatini for the control of the working class and the territory found very soon a like-minded counterpart in the aims of Fascism and that they eventually lined up with each other. The harmony reached on the economic level, between the monopoly projects of the industrial group and the government economic policy has been stressed several times,19 but on the social level what was perceived by the population of Colline Metallifere was almost an identification, even a symbiosis. The new regime, after eliminating or reducing the opposition to hiding, managed to develop and progressively implement its social policy. It therefore also displayed, like Montecatini, an interest for the wellness and the “moral and physical development of the Italian people”, both by boosting care and welfare services at a national level, and by instituting sporting events and recreational initiatives: always, of course, within a totalitarian vision of the State. The totalitarianism and authoritarianism of the fascist regime made it easier for Montecatini to achieve its goals: in short, a perfect integration of the intentions and methods of land management between the industrial group and the regime was achieved.

The regime wanted every social dynamic to support the construction of the totalitarian State and this led to industrial relations established in a heavily unilaterally influenced political context. This reflected the meaning of the “corporatism” advocated by Fascism, which was in large part, at least formally, achieved. This corporatistic context allowed Montecatini to maintain, and even strengthen, its hold on the organization of labour. Finally, Mussolini’s warmongering made the connection between fascist policies and the interests of the monopolistic group20 even more apparent.

3. War, reconstruction, political struggle

The constantly war-oriented policy of the government ended up giving Montecatini the opportunity for speculation that the mining company had been seeking since the beginning with the acquisition of the mine of Ribolla. After a serious crisis, the lignite market picked up again in 1935 and this led to the same kind of circumstances that had granted the mine its first important development following the First World War. The sanctions imposed against Italy as a consequence of the war in Ethiopia first and the interruption of trade flows due to the Second World War after, made the acquisition of foreign energy sources extremely hard. And so it was that, after several difficult years, Ribolla’s lignite found new outlets in the internal market. The national industry had to make do with less caloric fuels and families had to renounce imported coal for domestic heating. Lignite –especially compact lignite– became once again a sought after product. Extraction in Ribolla saw an unprecedented increase and the mine reached an employment level much higher than any nearby pyrite mines. On the other hand, this confirmed that the economic success of the mine uniquely depended on the state of war, or, at least, on the rise of a protectionist policy. The prosperity of Ribolla was a wholly specific and contingent one: the other side of the coin was the overall recession of the quality of consumption and a general worsening of the living conditions. In other words, that prosperity was sustainable only when created by a situation of emergency or by an authoritarian regime and it was completely incompatible with a peace economy, open to international exchanges in a perspective of development and well-being.21

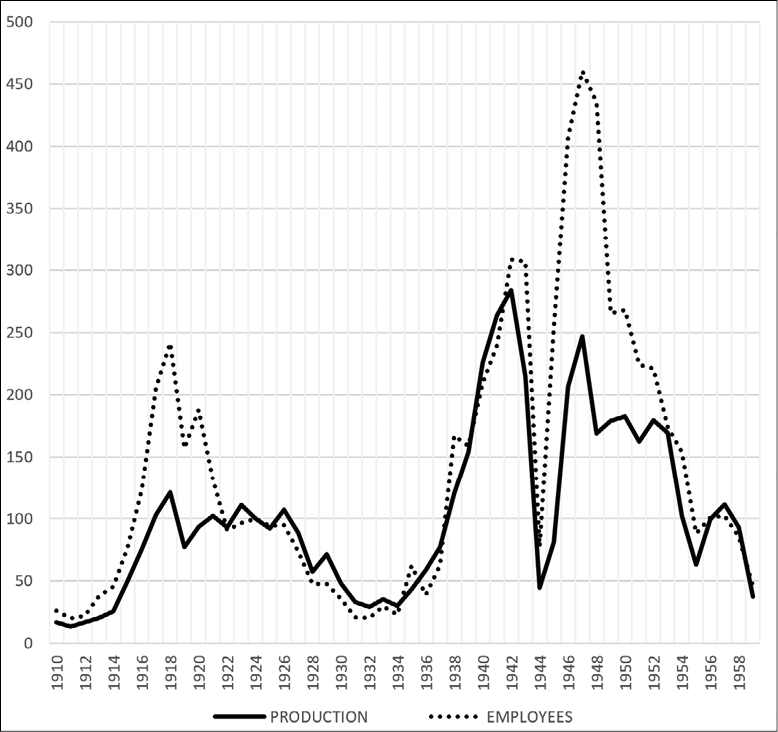

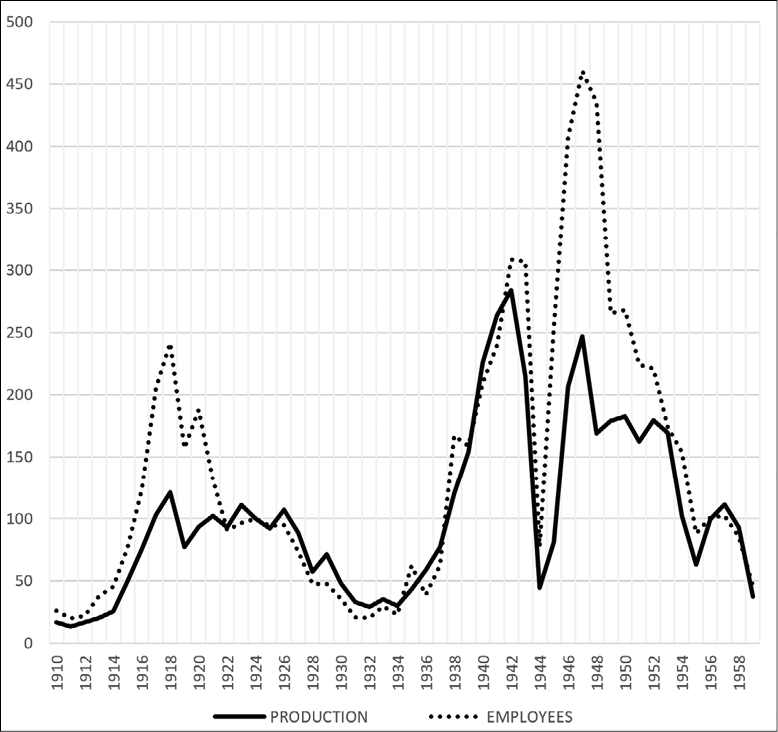

Figure 1, which represents the data of all the lignite mines in the Grosseto province, shows the trend I described above. The war years correspond to significant peaks in both production and employment. In particular, it can be seen that employment grows in those periods proportionally more than production. It should be noted that the level of employment reached in the two post-war periods –in 1920 and much more in 1947– also corresponds to moments of great strength in the local workers’ movement.

It was not difficult, however, in 1947, to foresee the difficulties and contradictions in which the labor movement would soon find itself, once those particular conditions had disappeared: on the one hand, the necessity to protect labour and employment, as it is natural for any workers’ union; on the other, the evidence that those necessities would become more economically unsustainable as the demands for peace and progress the movement advocated for were being satisfied.

The passing of the war front, as the Allied troops advanced toward the North of Italy, had caused alternate stops to all activities in the Maremma mines and some damage to the plants. The workers, for their part, had done everything they could to hinder the dismantling of the apparatuses during the German occupation. Afterwards, they reunited under a reborn unitary and democratic union and they strived for a quick resumption of the production. After the fall of Fascism, Montecatini, just like most large industrial enterprises, opted for the governing body to be supported by a management board that included workers representatives. Similar boards (Consigli di gestione) were instituted in every dependent unit and this included the mines. Such institutions never affected the companies’ management in depth: they mostly held the formal function of signalling the political change and, after the company representatives withdrew from them, only of supporting the union demands of the workers. These, while the collaboration lasted, were however very modest, despite the strong support of the masses that the union had. 22

Montecatini had to come to terms with the strong presence of the political left on the Maremma territory and in particular of the Communist Party, which was no longer illegal and therefore able to attract grassroots support. Such a presence became apparent with the democratically won control of the local administrations (municipalities and provinces) and of the workers’ unions.23 Notwithstanding the union split of 1948, which in any case caused a serious fracture of the until then unitary labor movement, the left trade union, CGIL, remained by far the strongest union on a national scale and particularly in Maremma, where the Miners’ Union represented its most numerous and significant section.24 The tradition of the labour movement, consolidated since the last years of the 19th century and strengthened by the recent experience of the Resistance against Nazism and Fascism, provided the ideological basis for the new structure of the local power, to which the majority of the miners greatly contributed with their support. Henceforth, any reference to the “miners’ movement” will indicate the political and trade union left in the area, that is the Communist Party and the Miners’ Union of CGIL, which were supported –not without contrasts, as we will see– by the working class. The workers’ “grassroots initiative” was an essential element of such a movement.

The management of Montecatini was only partially touched by the purge (“epurazione”)25 and it initially did not avoid a relationship with the new local political order. In return, the Company wanted its decisions about the management of the mines not to be hindered. As far as the mine of Ribolla was concerned, after the first market difficulties began to appear at the end of 1947, the Management decided in favour of a progressive downsizing. Consider that, although between 1946 and 1948 the price of imported coal increased from 14.70 to 19.55 USD/ton, its quantity increased by almost 60%. In the same period, the price of oil remained substantially unchanged, against an increase in the quantity imported by more than 15 times.26 It was therefore the opening of Italy to international trade that put the internal production of solid fuels in difficulty and in particular the extraction of lignite.27 The difference between individual yields is the indicator that best represents the situation: the average daily yield of the American miner, who generally worked “in open pit” in highly mechanized sites, was close to 6 tons, while in Ribolla, in the underground, with the use of explosives only and the percussion drill, it barely reached, in 1950, 350 kg. 28 In 1947 the yield in Germany was already 920 kg.29 In these conditions, the support offered, albeit with some caution, by Montecatini to the liberal governmental economic policy and to the process of market opening might seem a paradox: in reality it is only the confirmation of the residual and speculative role of lignite production within its industrial system.30

At the end of 1947, therefore, attempts by the Company began to reduce working hours first, then employment. The tension with the workers grew higher month after month and the climate of collaboration that seemed so solid after the war started to quickly deteriorate. Graph 1 shows the rapid fall in both production and employment after 1947, even if the second curve was initially slow to follow the almost vertical trend of the first: a sign that the union, until that moment unitary, was able at first to oppose some resistance. The union went from being initially willing to acknowledge the objective difficulties of the Company –so much so that it came to agree on some limited downsizing– to an increasingly strong refusal. Montecatini showed a similar rigidity: to uphold its points it could point at the unsold piles of lignite that, day after day, grew higher by the mouth of the shafts. In the spring of 1948 the Company could place on the market 14,600 tons of mineral per month, against an average production of 16,500 tons.31 The time for mutual understanding was over.

The worsening of the relationship was undoubtedly influenced by the national political situation, which was changing again after the left wing parties had been excluded from the government and then defeated in the elections, while the pro-government currents separated from the unitary union. The local consequences of this situation became soon apparent, even if, for the most part, the municipalities remained firmly under the control of the Left and the unions born after the split found little support. The political strike, to which the miners resorted more and more often thereafter, was the proof of a progressive politicization of the social conflict. The miners militating in the Union and in the Communist Party became convinced of being part of a revolutionary movement whose goal was to subvert the bourgeois order, well represented in Maremma by the Montecatini monopoly, in order to establish Socialism: an ancient dream still able to warm the hearts of the people.32 The counterpart proved to be equally determined to stand in the way of such a movement, so much so that it ran the risk of giving credit to those revolutionary ideas far beyond their objective capacity, and so the Company received material support from the central government and its local representatives (Prefect, Quaestor, Chief Engineer of Corpo delle Miniere, police). The government parties and their newspapers were all sided with Montecatini. The reason –in truth, not completely specious– most often opposed to the mobilization of the workers was that it was exploited by a specific political party and even –and here the exaggeration was apparent– in favour of a foreign and potentially adverse power, namely the Soviet Union. It is easy to understand how the Cold War climate made the conflict even harsher. What was really at stake, however, was the control of the territory. The Montecatini social system, based on close collaboration with a political power operating without opposition at both the central and peripheral levels, as was the fascist regime, was no longer viable. Now Montecatini faced a political antagonist endowed with widespread popular consensus and capable of controlling local institutions. Its power was therefore concretely threatened. It should not be forgotten that the nationalization of monopoly firms, and in particular of those in the process of demobilization, was still, at least formally, an objective of the PCI with regard to economic policy.33

The Ribolla mine was still the one with the highest number of workers, even if with an increasingly uncertain future, and this made it the centre of the reclaiming and political movement of the Colline Metallifere area. The community displayed great solidarity for the miners and this made up for, and partially hid, an objective weakness of the union, which became more and more apparent over time.

As we have seen, “politics’’ had snuck into the mine during the Fascist regime, bending industrial relations to match the objectives of the totalitarian state. Then, in the first years after the war, the reconstruction needs of the country had silenced any reclaiming autonomy. Now, in a completely new context, though the class struggle was no longer suffocated by corporatist or solidarity ideologies, “politics” was still influencing the behaviour of the Union. This led to a risk of misunderstanding what the real power relations in the company were and of jeopardizing the achievement of realistic trade union goals.34

4. Labour unrest and piecework

The political confrontation could not completely hide the specific content of the social conflict: the opposition between the concrete needs of the workers and those of capitalist production. Such a specific radicalism fueled the spontaneity of the labour base, often finding a way to surface. The workers reclaimed autonomy but they were not fully aware of their vindications. There were therefore periods during which the spontaneous initiative of the workers seemed to prevail, followed by others during which the local Communist Party, in line with the central directives aiming at moderating the conflict, managed to strengthen its control on the movement. The Miners’ Union was right in the middle of this conflict, dragged sometimes to one side, sometimes to the other. The frequent alternation of the leaders, both in the Miners’ Union of the province and in the section of Ribolla, was a symptom of such a situation.

The miners of Ribolla created a sort of “reverse strike” against the reduction of the working week: workers scheduled to rest would show up to work and go down the shafts to do their jobs. This was, in February 1949, the first big mobilization on strictly labour issues that took place in Maremma during the postwar period. It marked the start of a series of episodes and behaviours that would become a constant of every miners’ demonstration in the following years: the solidarity from all the other mines, the presence of women on the village square and at the mouth of the shafts to support the men’s vindications, the heavy and menacing law enforcement presence.

Still, the negotiation on the work schedule went ahead and Montecatini was forced to suspend and postpone the measure, in view of the commitment from the Union to collaborate to obtain a daily quota of 500 Kg/man35. This was to be the last declaration of openness towards the Company: there was no talk of collaboration thereafter, except as a polemical reminder of the work done in previous years to save the plants and to resume the production.

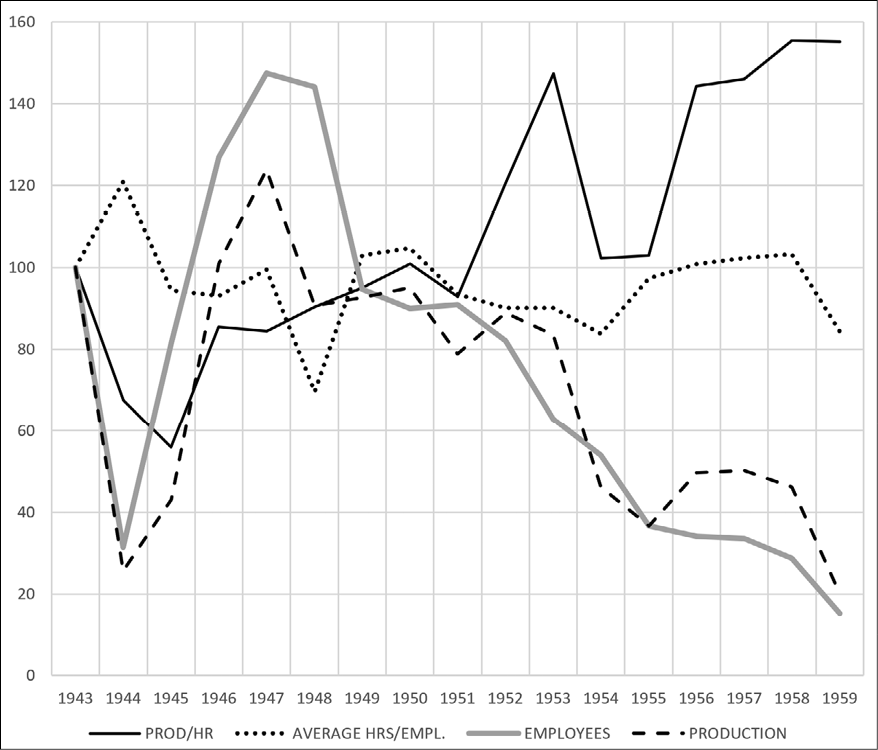

I shall omit here the details of the mobilization and the various stages that the miners had to go through in the conflict with Montecatini and the forces that supported it. I want to focus instead on the subject of the conflict, which fundamentally gravitated towards the attempt on Montecatini’s part to increase the productivity of the mine. If we look at Graph 2, referring only to the Ribolla mine, we see that, before making a drastic cut in labor (1949), Montecatini reacted to market difficulties, which required a decrease in production, by intervening precisely on the work schedule. In fact, between 1947 and 1948 there was a sharp reduction in the hours worked by each employee, while the union still managed to somehow defend the level of employment. When the layoffs then began, the average hours worked began to rise again. In this way, Montecatini managed to keep productivity stable –even slightly growing-, at least until 1950. The curves of the graph actually show, as a whole, a substantial ineffectiveness of trade union action.

“Super exploitation” was the slogan coined by the left propaganda to refer to the increase in the work pace, the cut of the work time and the increase of the workload in factories. In such a mine with a low degree of mechanization as the one of Ribolla,36 this could only mean the incremental use of piecework in its most classic and simple form: amount of mineral extracted per time unit, usually calculated for each team of workers. In this sense, “super exploitation” depicted a real state of affairs. Miners knew from everyday experience that the organization of the work in the mine hinged primarily on piecework. After all, it was no mystery that piecework was the object of the occasional, informal negotiation between single teams of miners and the department heads, who served as proxy for the management of the mine. These negotiations ran in parallel with the official agreements and often overruled them. Each team consisted of two or three workers, among which there always was at least a miner and a unskilled labourer. The teams were able to determine the amount of felled ore (tout venant) or –in the case of preparatory work– of waste, with good approximation by simply keeping count of the loaded wagons that were chalk-marked with the identifier of the team, channeled from the worksite at the base of the shafts, caged and lifted outside. Obviously the wages for piecework –which were the actual object of the negotiation– varied according to the kind of work that the team had to perform and, in particular, the type of terrain or rock they had to fell. However, it was not uncommon to have an agreement made on the spot depending on the type of work required.

It must be kept in mind that the application of Tayloristic methods to mining work had never gone past some sporadic experiment. The Montecatini mines attempted to rationalize the piecework system at the beginning of the 1930s by introducing the “Bedaux” method, but this was opposed by the workers and therefore failed. In particular, during the Fascist period there was a spontaneous uprising against the new system (a rebellion that was to be reclaimed by the official union at a later stage). The regime silenced the protest, but had to concede and eventually ban the use of the Bedaux method inside the mines.37

In January 1951, the Miners’ Union of CGIL –as ever in complete disagreement with the secessionist unions (CISL e UIL)– attempted to change the traditional system, in order to challenge the exploitation of piecework carried out by the mine management. A complete ban of piecework, advanced both after the First and the Second World Wars, had been quickly dismissed for lack of support from the workers, after some initial enthusiasm. This time, the Union proposed a collective piecework system, extended to all the workers, including those who worked on the outside and not limited to the advance teams. The goal was to distribute the “economic benefits” of piecework (according to criterias that I shall not illustrate here) amongst everybody, as it was carried out everywhere in the mine. The claim concerned all the Montecatini mines in Maremma (Gruppo Miniere Maremma), but, with respect to the Ribolla mine, it primarily aimed at contrasting the reduction of employment by limiting the indiscriminate use of incentives, through the control exercised by the workers themselves on the work distribution. Essentially, it was a productivity bonus to be negotiated with the union. It was obvious that the proposal had a solidaristic and fundamentally egalitarian meaning, whose aim was to strengthen the workers’ front. On the other hand, it impacted on the negotiating activities by eliminating or at least reducing the opportunities for spontaneous negotiations, which in turn weakened the negotiating power of the union. Had the claim been successful, it would have had important consequences: the workers would have been able to control the organization of the work (controllo operaio), thus seriously limiting the power of Montecatini inside the mine.

The turmoil to get collective piecework, which began in February, ended at the beginning of July, having required heavy sacrifices from the mine’s workers and their families, but without reaching its main goal. Later, it was called the Five Months’ Struggle. CGIL had to settle for minor improvements, while also having to defend itself from the accusation from the secessionist unions of having led the workers to the brink of ruin. Montecatini was strengthened by such a showdown, while the miners’ movement was weakened, even if the social consensus around it and the trust in its political representatives was not compromised. The union side of the miner movement was weakened, but its political strength was confirmed and even growing.38 The reflection of these events on the main (non-financial) quantities that measured the mine performance is clearly shown in Graph 2. In coincidence with the strikes, the hours worked obviously decreased, but the even more accentuated decline in production, while employment remained stable for the moment, produced the interruption of the moderately upward trend of productivity.

5. Productivity and safety

The accusation of an “industrial demobilization” was frequently used by the Left against the Italian industrial employers in that period.39 It denounced the alleged will to reduce the productive base of the country and to damage, with the assistance of the government, the bargaining power and life conditions of the working class. It was still a subject of agitation and propaganda, however, for the Ribolla mine, as well as for other industrial environments, it described the experience of the workers in the workplace and what they witnessed of the decisions and behavior of the management. It was apparent in the way the mine was run, in the organization of labour and most of all in the incessant proposals of layoffs that, notwithstanding the opposition of the Union, began to be fulfilled. Everything pointed to a “demobilization” plan.40

“Montecatini wants to shut down Ribolla”: this was the fear that spread among the workers and the population, which the union and political left easily managed to use for their national campaign of denunciation against “demobilization”. After all, as I mentioned above, such an outcome was not unreasonable given the trend of the lignite market and the prospects of the national economy. 41

To these fears and accusations, Montecatini kept on answering by reaffirming the will to keep the mine open, in spite of its evident economical disadvantages.42 The Company wanted to prove that it cared about the well-being of its employees and their families, at least as much as it cared about profit. It was even willing to renounce its legitimate interests in order to keep the mine open and spare the population the discomfort caused by the shutdown. Some of the public statements released by the Company gave the impression of coming from a philanthropic institution rather than a capitalistic company. This attitude was the latest expression of the paternalism that the Company had always displayed in its social interventions and that had found its best expression, as seen, under the Fascist regime. A newspaper supporting the government parties presented the situation in Ribolla with these words: «It seems almost a paradox. That something different, compared to other mines (those of pyrite to be clear) exists, you realize from the fact that the ore that comes to light in Ribolla does not leave the place with the same intensity; it is easier, indeed, for it to pile up in the yards outside the mine. And let’s see, then, what causes combine to create this strange situation. First of all, the Company claims that the mine is passive (we are talking about hundreds of millions a year, of which 60 are destined for transport, such as buses for employees and to take children to school, etc.) and that it is kept open only for social reasons».43 This was ordinary controversy. Montecatini, however, was well aware that the closure of the mine would have provoked a very intense social upheaval, which would not be confined to the Ribolla village, but would have extended to the entire mining area and to the entire province. The Left would certainly have taken the lead, putting the government front in difficulty, the solidarity of which the Company was in dire need of. More than the trade union strength of the miners’ movement, Montecatini feared its political strength, which manifested itself in the management of local administrations and therefore in the government of the territory, with significant results at the level of the national parliament.

Once the conservation of the traditional system of piecework was secured, Montecatini nevertheless specified its business goals. Since it continued to deny the hypothesis of a shutdown, it couldn’t but guarantee the production with a reduced share of the workforce. This implied a drastic reduction of the maintenance time dedicated both to the apparatuses and to the mine itself –obviously excluding any further development– to focus on the extraction of the mineral in the most productive sites. The excavation of the deepest shaft in the mine, Shaft 10, was completed in 1951, but in spite of this from then onwards new search activities were suspended, many active sites were abandoned and all auxiliary and preparatory jobs were slowed down.44 But above all the mining method was changed.

The system introduced by the new manager, who had arrived in Ribolla after the Five months’ Struggle, involved mining in dead-end working sites, with a single entry and exit passage for both air and personnel. The Regolamento di Polizia Mineraria (Mine Regulation), issued by Royal Decree n. 152 of January 10th 1907, while allowing for exceptions, prescribed that mining sites must have two exits (art. 9) and that the inward and outward air flows must be independent (art. 28).45 A head tunnel, connected to the base tunnel, would have provided a second exit and insured regular air flow. The lack of this second tunnel resulted in significant savings for the Company. This new system also called for the exhausted stopes to be abandoned and for their roofs to collapse, instead of being filled with mine tailings. Consider that, in view of the characteristics of the Ribolla deposit, “backfilling” was explicitly recommended a few years before by Luigi Gerbella, one of the leading experts in mining, who, since 1938, had been the director of the mining District of Florence, from which the Maremma mines at that time depended.46

The Ribolla mine was a difficult mine that required particular care and considerable maintenance costs. At the beginning of its exploitation, the lignite seam appeared to extend for just a few metres below the ground, even surfacing in some areas, but the successive mining, following the irregular shape of the bank, ended up reaching increasing depths. The subsoil was also subject to high ground pressure, which caused the shrinkage of tunnels and winzes, damaging their scaffolding. The scaffoldings used in this mine were not only the traditional chestnut wood ones: some areas had required masonry structures, while in others was attempted the use of metal, which was often deformed by the pressure of the rock. Besides, just like in every other coal mine, firedamp was a risk: a serious danger in addition to all the other threats inherent to underground work. It is true that Luigi Gerbella himself, in the 1948 edition of his mining manual, highlighted the economic benefits of mining by landslide of the “roof”. Yet, while acknowledging that «the conditions of safety in the sites are not, in general, worse than those where other mining systems are adopted», he also claimed: «These methods are not advisable when they can easily cause a fire».47 This was the case of the Ribolla mine.

After all, the “backfilling” method was the traditional method generally adopted in the Maremma mines, which involved the mining of the mineralized banks “by horizontal descending slices”, that is to say from the top down. Using this method, the accurate filling of an exhausted site allowed for the stabilization of the adjacent stopes and the lower levels. This guaranteed the stability of the mine and the safety of those who worked in it, by avoiding empty spaces and uncontrolled land movements.48 It is obvious that not placing the backfill meant a drastic reduction of the work time not directly involved in the extraction of the mineral, and therefore a reduction of its cost per unit. Inevitably, it also foretold a quicker exhaustion of the vein, regardless of the economic results.

This new mining system was authorized by Corpo delle Miniere of Grosseto, thus denying, with an explicit derogation, the recommendations previously issued by Gerbella about the mine of Ribolla. The reason for this, explicitly acknowledged by the Chief Engineer Tullio Seguiti –so by a state official– was the necessity to significantly improve productivity, in view of the fact that the average production of Ribolla in 1951 had been of just 314 Kg employee/day, while in French mines it had been of 858 Kg and in the American ones of more than 7,000 Kg.49 The same ministerial office prescribed the realization of a ventilation tunnel that should have guaranteed the air flow, but the mine management never completed it, while officially declaring a progress of the work that did not correspond to reality.

In the intentions of the manager of Ribolla, a significant increase in work productivity and a lowering of production costs, would allow the mine to regain competitiveness. From his point of view, this was the only way to keep it open and the condition to guarantee a margin of profit for the Company before the shutdown. It was however inevitable that the maintenance of the underground areas, the good functioning of the air flow and the safety of the personnel would be sacrificed. It meant an overall worsening of the conditions, which he however considered sustainable as it would allow for production to continue.

The upward leap in productivity recorded in 1953 (Graph 2) is therefore to be attributed to the policy adopted by the new management of the mine regarding the discipline of the workers which I will mention later and the mining method. In fact, nothing is known of any investments in technology. The diffusion that took place in that period of metal reinforcements to replace wooden ones may have influenced production costs, but could not have consequences on productivity. The level of mechanization remained essentially unchanged. On the other hand, there was a slight decrease in production in the presence of a significant reduction in employment: having the possibility to lay off the manpower, the management of the mine avoided intervening on the working hours, thus keeping the average hours worked constant. The data show that, once again, the miners’ movement was unable to effectively counteract the management’s action: its intervention was in fact limited to complaint.

6. Towards the disaster

After the defeat in the Five Months Struggle and the definitive exclusion from any participation in the organization of the work, the miners’ movement aimed for the strenuous defense of job. In spite of dramatic episodes, like the occupation of the mine in March 1953, it had little success in fighting the layoffs imposed by Montecatini.

The spontaneity of the base had been channeled into a permanent state of turmoil that amplified the political aspects of the conflict. The Union, however, failed to recognise that the power Montecatini still held over the territory ultimately depended on the centrality of the mine and on the control exercised over the work. It was late to realise the relevance of the recent changes in the mining systems and their consequences for the safety of the workers, or, at least, it was late to act upon them.50 It was only in the summer of 1953 that the Union began to draw the attention of the authorities and of the local public opinion to the safety conditions in the mine. It then launched a campaign to denounce the new mining system, pointing at the risks that it created for the workers and the mine itself.

Precisely after a firedamp explosion on July 15, 51 which wounded two workers, the increasing number of work accidents was connected to the changes to the mining system. The Ribolla section of the CGIL Miners’Union reported impressive accident figures: in 1952 there were 600 serious injuries and 2,400 minor ones, with an increment respectively of 42.8% and 33.3% compared to the previous year.52 Montecatini, backed up by the pro-government front and especially by Corpo delle Miniere, argued instead that the data concerning the increment of work accidents was completely random and contingent, while the tendency over a significant number of years displayed a reduction. The Company argued that the accusations were purely pretextual and motivated by political intents, while the panic that was spreading was completely unreasonable. According to the technicians of the Mining District, the accidents that required more than three days of hospitalisation in 1952 were 409, and among these only 102 required a leave of over 20 days. The remaining 1,848 cases were trivial accidents resolved with simple treatments. The increment in the number of accidents over the last few years was for Corpo delle Miniere undeniable, but it concerned all the mines in the area, so the new mining system introduced only to Ribolla could not be blamed. Besides, Corpo delle Miniere believed that the two fatal accidents that took place in Ribolla in 1953 could not be attributed to the new mining system.53 The management of the mine excluded that the presence of firedamp could reach dangerous levels. However, this does not mean that accidents such as the one of July 15 due to firedamp explosions did not occur over the years.

The campaign of denunciation against the management of the mine intensified thereafter and it led to the dismissal of the Secretary of the Internal Commission, after an explicit attack found in an article he published in the newspaper of the Communist Party, L’Unità. Safety in the mine had been an overlooked theme in the post-war period, mostly left to the good will and reciprocal trust between the management and the workers. Now it had become the center of their confrontation, in a climate of rising tension.

Montecatini confirmed on several occasions that the shutdown of the mine was not part of its plans, contrary to what most people had come to believe. This was the charge that the Company feared the most, as it had the potential to regroup the union front. Even the secessionist unions, presented with the continuous reduction of employees, feared an eventual shutdown. However, in the conditions created by the new method and in the absence of investments in new research and new technology, the intention to continue the business could only translate into greater exploitation of labor and greater risk for the workers. This, at least, was the opinion of the Miners’ Union of Ribolla.54 Anyway, it seems hard to deny that the Company wanted to establish a “predatory” way of mining in order to exploit any residual profitability and accelerate the depletion of the deposits, while economical conditions were still favourable.55 This change in the production was accompanied by an exacerbation of the internal discipline, which was already extremely strict, as it generally is in all mines. On the arrival of the new manager disciplinary actions against the miners became much more frequent, and this too was denounced by the Union, according to which Montecatini had established «a despotic, crushing and vexatious policy against the workers».56

Was this the mission with which the new manager Riccardo Padroni was entrusted by the central management? The Miners’ Union, in the letter of August 7th, 1953, to which I have already referred, asked the question whether there was a “pre-established” plan by the Montecatini Company which the local management was obliged to comply with or the situation that had arisen depended solely on the discretionary decisions of the local management, “unable” to carry out his task. In reality, it does not seem that the Union and, in general, the miners’ movement made any distinctions in the matter of responsibility, if what Tullio Seguiti, Chief Engineer of the Corps of Mines, reported to the Ministry of Industry is true: «In recent weeks, trade unions and left-wing parties intensified a campaign against Montecatini Company both in favour of trade union issues and as regards safety in mines […] signatures are being collected for a petition that should be presented to Parliament regarding the protection of miners’ lives».57

The miners’ movement proved to be able to make a precise analysis of the conditions of the mine and to develop a precise critique of the policy of the Management and the Mining District,58 but there was no possibility of establishing a dialogue because the counterpart considered all its proposals a pretext to fuel political unrest.

The conflict between the miners and the Montecatini was therefore sharp, the tones harsher and harsher. The disaster happened at the peak of this tension.

7. After the disaster

As I have already mentioned, the dynamic of the accident has never been clarified. All the possible reconstructions, which the judges examined for a long time, are open to objections and reservations, but the final ruling accepted the gas explosion as the cause of the tragedy. Today that still appears as the most plausible hypothesis.

The management of Montecatini and of the Mining District were acquitted only because the judges could not establish a direct cause and effect relationship between their acts, or their omissions, and what had happened. They confirmed that for several days there had been an active combustion in an abandoned tunnel in the lower part of the underground, at level –260, which could not be extinguished even if it had been constantly monitored. They also took notice that, over the two public holidays preceding the tragedy, during which there was no personnel in the underground, the air flow had been inverted without any apparent reason, or maybe in the attempt of containing the fire. The formation of a firedamp pocket was plausible, but it was not possible to establish its origin nor how the explosion was triggered. This was enough to grant the acquittal. There were of course attempts on Montecatini’s part to draw the attention of the judges on the incompetence or the negligence of the workers, while some witnesses –obviously very indirect ones– 59 even hinted at sabotage.

In particular, the sentence excluded that the new mining system, on which the denunciations of the Miners’ Union had focused before the accident, was at the origin of the disaster. This happened in spite of CGIL continuing to point to its danger, especially where landslides in exhausted stopes were concerned, as they could create uncontrolled empty spaces for the gas to accumulate. It is understandable that the discussion of the technical details, which at the time required a confrontation among the most renowned mining experts, produced theories incompatible with each other but equally plausible on the scientific level. The final outcome was that it was impossible to reach a unanimous decision on what the truth was.

I have to omit the details of this discussion, but I believe that, almost seventy years later, it is possible to establish a few key points:

1. The explosion itself showed that the general conditions of safety in the mine were not adequate, in contrast to what Montecatini claimed.

2. The specific recommendations that Corpo delle Miniere had given for the mine of Ribolla in the past were motivated by the particular conditions of that mine. It could therefore not be considered on a par with other mines as far as safety measures were concerned.

3. The waiver conceded by Corpo delle Miniere to the prescriptions that it had previously issued caused a reduction of the safety level in the mine. The argument continuously brought forward by Montecatini that the work underground could never be as safe as the work on the outside did not hold.

4. Listing the mine as having a low probability of firedamp formations in dangerous amounts could not exempt the management from adopting the necessary measures for preventing potential explosions.

5. The presence of an underground fire for several days should not have been considered as a normal occurrence, compatible with regular work activities.

6. Even if the cause of the explosion cannot be definitely identified with the mining system, not enough attention was given to the air circulation in the underground, a fundamental factor in order to make the working conditions bearable and to avoid the accumulation of gas. Moreover, the opening of the return-flow tunnel prescribed by Corpo delle Miniere had been delayed.

It must be asked whether the politicization of the social conflict might have prevented the miners’ movement from making a less catastrophic, but more precise denunciation of the risks and whether that would have been more effective.

We must however be true to the facts. It is understandable that, after the disaster, the rage of the miners and of the population was irrepressible. I will not recount the most clamorous episodes in which the popular indignation came to the brink of explosion, the first of which was the funeral of the victims. During the ceremony, the only speaker to be applauded rather than booed was Giuseppe Di Vittorio, Secretary-General of the CGIL. A desire for vengeance is also present in the fictional reconstruction written a few years later by Luciano Bianciardi. It is a hyperbole whose function is to express the self-irony of the writer, but it is also effective in describing the climate of the time and it leaves a bitter taste of impotence, which is also rather realistic.60 What happened afterwards to the mine and to the village of Ribolla showed that, even if the miners’ base movement had apparently been strengthened by the tragedy, it was still unable to pursue its main goal, which was to preserve the activity of the mine.

By this point, the conflict between the miners’ movement and Montecatini seemed irreparable and destined to be resolved with the victory of one part and the demise of the other. It seemed that the very trial against Montecatini had to have this outcome, because such was its political meaning. It is important to keep in mind that the nationalization of the mines was still on the political agenda of the Left at the time. Nonetheless, even if the miners received more and more solidarity and Montecatini appeared to be crushed by the enormity of what had happened, the climate was changing.

It was as if the local community, notwithstanding the indignation for what had happened, started to seek a sustainable way out. The desire for compromise began to emerge from the propaganda. Little by little, the political passion faded away or, at least, it was channeled in a different direction, while the mine progressively ceased to be the center of the local microcosm. Even at a national level, after all, the political situation was veering in favor of the Left (the so-called “svolta a sinistra”), notwithstanding attempts to oppose such a trend.61 The industrial relations on the workplace were brought back to the specific level of labour negotiations, where the confrontation between the sides and their material interests prevailed on a more general political meaning. I do not mean to say that from this moment onward labour disputes found easy solutions and did not require strikes and other forms of struggle. I only mean that the institutional character of the Union and of the Internal Commission imposed itself over every other demand or aspiration, finding their counterpart open to confrontation on this terrain. The contractual initiative was backed up by a new attention to the miners’ problems on the part of the Parliament, which led to significant legislative achievements in their favor, supported across parties. It does not seem risky to argue that after the first moments of exasperation, the tragedy of Ribolla, despite the great pain it caused, helped to generate the new political climate.

Corpo delle Miniere stopped obliging Montecatini’s desires and passively accepting its financial requests, while in the past those had been its primary concern, sometimes even to the detriment of the safety of the employees. The new Chief Engineer established precise conditions for the resuming of the activities and demanded that they were respected, even against the pressures of the workers’ organizations, that were interested in resuming operations as quickly as possible.62 In 1955 the mine was once again active, employing 780 workers. The construction of an auxiliary gallery was imposed to improve the ventilation system, an expensive job which Montecatini, it must be said, did not shy from carrying out. The mining system introduced by the previous management was finally accepted by the Union and the workers alike, since it was evidently considered not dangerous under the right circumstances.

Most importantly, the alliance that had supported Montecatini over the years finally began to crack. Even the unions (CISL e UIL) that competed with CGIL began to find their autonomy and were no longer ruled by the employer’s interests. The pro-government political forces, including Democrazia Cristiana (Christian Democracy) began showing significant nuances when dealing with mining issues, abandoning their previously unquestioned support for the ruling class. The miners’ movement did not have to face a solid hostile wall anymore. After all, the secret negotiation between the lawyers of CGIL, supported by the Italian Communist Party, and Montecatini to compensate the families of the victims indicates that the actual terms of the conflict had changed: as a matter of fact, a mutual recognition had been achieved. Montecatini had to give up its absolute control on the territory and acknowledge that its presence had to come to terms with a close social fabric, characterized by solid political references, which demanded recognition and inevitably excluded the Company from certain decision-making processes.63 Most of all, it had to acknowledge that the social fabric formed in the post-war period could not be linked to a transitional experience, deemed to come to a close with the end of the reconstruction period. The Left, on its part, finally accepted that industrial enterprises had a capitalistic operational autonomy, which could be limited by trade unions or general economic policies, but could not be completely rejected. As a matter of fact, the progressive reduction of the number of employees in the mine of Ribolla over the four years of the trial against Montecatini was mostly uncontested. It is possible that the investments that had been made to upgrade the underground had made the workers hope in a future for the mine, even if with only a few employees. However, by the time the sentence of the court of Verona was finally delivered, the local community had already found a new arrangement: an equilibrium that could do without the mine.

As we have seen, the trial ended with an acquittal verdict. Shortly after, Montecatini sent Corpo delle Miniere a waiver of the license for the Ribolla mine, and then ceased any activity of extraction and maintenance. At first, Corpo delle Miniere tried to avoid the shutdown, arguing that, even with a few employees, the plant could potentially continue its activities for some years until the depletion of the mineral. It had to however accept Montecatini’s decision and did not support the self-management attempt on the part of a cooperative of miners; an attempt that, in fact, did not succeed.

The firedamp explosion actually meant the end of the mine. The shutdown was just postponed by a few years, for obvious reasons of opportunity, on which the trial had a great impact. However, during the years of the trial, relationships began to shift and conflict was replaced by civil confrontation and compromise. It can be said that it was the trial itself that kept the mine alive for a few more years, just until there were the conditions for a shutdown that would not result in further social unrest. The miners’ movement could not avoid a result it had greatly feared and long denounced as a capitalistic maneuver that would bring unemployment and misery. These kinds of consequences also followed the accident, after which many miners had to find another job and some decided to emigrate, as it had sometimes happened in the past, even if Montecatini was able to re-employ a good number of workers in other mines. The families of the victims had to endure the most severe consequences, as is always the case, as no compensation can ever be adequate.

Still, compensations were paid, and for years the miners’ widows were criticized in Ribolla and the surrounding area, because many believed that through money Montecatini had broken the unity of the people and granted its acquittal.64 As we have seen, the disappointment was great, particularly because many viewed the trial as their last chance for payback, not least political, against Montecatini. The Communist Party, however, managed to handle this complex situation and granted the essential unity and cohesion of the social fabric. Without assuming sharp positions, but without disowning the myths and ideologies that grounded its identitary language and regaining the strength of the miners’ movement that was the foundation of such a collective identity, it adopted a pragmatic behavior that allowed it to maintain a relationship of trust and approval even with the families of the dead miners, who had received a compensation also through its mediation. This situation is a good example of what was called the “duplicity” of Italian Communism.65 On this basis, the Communist Party managed to rule the process of progressive “tertiarization” of the local economy, even in the following phase, during which the pyrite mines were shut down for good. The end of the mining economy left only a few isolated industrial settlements in the area: insufficient to absorb the expelled manpower and to reproduce a local working class.

It was the end of an era. In the public eye, Socialism was becoming a more and more abstract concept66 and the working class itself a vanishing entity.67 Moreover, Montecatini itself ended up dissolving, through a complex sequence of events that I cannot illustrate here. What was left was a local administration system founded on the labouring tradition and committed to facing the new challenges that the process of modernization was going to present. Did it succeed? Can it still succeed, at least where such a thought resists, even in the absence of traditional political forces?68 These are questions that the historian asks, but cannot answer.

The incident of Ribolla remains to indicate how working conditions require a specific attention that must originate first of all in the experience of the actual workers, who every day have to deal with the technology, the risk and, in general, the demands and strategies of the capitalistic mode of production. These are the terms of a conflict that can certainly be represented as class struggle, but on which “politics” has often imposed itself almost to the point of denying its autonomous relevance. At times, politics has prevented solutions that, while always contingent, could improve job performance and establish new arrangements between the sides, more respectful of the safety and of the dignity of the workers.

Table 1. Production and employees in the lignite mines of the province of Grosseto

|

Year |

Production |

Employees |

|

tonn. |

n. |

|

|

1910 |

19,062 |

248 |

|

1911 |

15,067 |

190 |

|

1912 |

18,800 |

212 |

|

1913 |

22,700 |

360 |

|

1914 |

28,903 |

432 |

|

1915 |

56,043 |

730 |

|

1916 |

84,230 |

1,175 |

|

1917 |

115,330 |

1,961 |

|

1918 |

135,774 |

2,304 |

|

1919 |

86,303 |

1,499 |

|

1920 |

104,459 |

1,792 |

|

1921 |

114,451 |

1,255 |

|

1922 |

104,132 |

865 |

|

1923 |

124,447 |

919 |

|

1924 |

112,138 |

954 |

|

1925 |

103,374 |

900 |

|

1926 |

120,207 |

904 |

|

1927 |

99,121 |

703 |

|

1928 |

64,211 |

452 |

|

1929 |

80,126 |

456 |

|

1930 |

53,677 |

339 |

|

1931 |

37,200 |

196 |

|

1932 |

32,396 |

195 |

|

1933 |

39,355 |

282 |

|

1934 |

33,691 |

221 |

|

1935 |

48,615 |

592 |

|

1936 |

65,674 |

371 |

|

1937 |

86,556 |

595 |

|

1938 |

134,846 |

1,597 |

|

1939 |

172,774 |

1,516 |

|

1940 |

253,090 |

1,999 |

|

1941 |

295,922 |

2,286 |

|

1942 |

318,472 |

2,943 |

|

1943 |

240,936 |

2,928 |

|

1944 |

49,863 |

740 |

|

1945 |

90,769 |

2,427 |

|

1946 |

231,433 |

3,884 |

|

1947 |

277,018 |

4,392 |

|

1948 |

189,619 |

4,154 |

|

1949 |

201,180 |

2,532 |

|

1950 |

205,050 |

2,559 |

|

1951 |

182,351 |

2,136 |

|

1952 |

201,574 |

2,110 |

|

1953 |

189,871 |

1,664 |

|

1954 |

114,685 |

1,470 |

|

1955 |

70,832 |

840 |

|

1956 |

111,577 |

962 |

|

1957 |

125,183 |

974 |

|

1958 |

104,140 |

815 |

|

1959 |

41,787 |

435 |

Source: data provided by Main District of Grosseto

Table 2. Production, employees and worked hours in the Ribolla mine

|

Year |

Production |

Employees |

Worked Hours |

|

tonn. |

n. |

n. |

|

|

1943 |

240,936 |

2,928 |

5,712,356 |

|

1944 |

49,853 |

740 |

1,777,681 |

|

1945 |

90,769 |

2,427 |

4,082,104 |

|

1946 |

231,443 |

3,884 |

7,072,442 |

|

1947 |

277,018 |

4,392 |

8,565,059 |

|

1948 |

189,619 |

4,154 |

5,131,891 |

|

1949 |

201,180 |

2,532 |

5,050,947 |

|

1950 |

205,050 |

2,259 |

4,643,408 |

|

1951 |

182,351 |

2,136 |

4,929,027 |

|

1952 |

201,574 |

2,110 |

3,785,897 |

|

1953 |

189,871 |

1,664 |

3,010,083 |

|

1954 |

114,685 |

1,470 |

2,417,004 |

|

1955 |

70,832 |

840 |

1,623,314 |

|

1956 |

111,577 |

962 |

1,762,653 |

|

1957 |

125,183 |

974 |

1,954,580 |

|

1958 |

104,140 |

815 |

1,562,944 |

|

1959 |

41,787 |

435 |

676,466 |

Source: data provided by Main District of Grosseto

Abbreviations

AAIG-ACMM = Archivio Associazione Industriali Grosseto – Aziende Cessate Montecatini

ADMG = Archivio Distretto Minerario Grosseto

CGIL = Confederazione Generale Italiana del Lavoro

CISL = Confederazione Italiana Sindacati dei Lavoratori

PCI = Partito Comunista Italiano

UIL = Unione Italiana del Lavoro

Bibliography

ACCORNERO, A. (1973): Gli anni ’50 in fabbrica, Bari, De Donato.

ACCORNERO,A. (1998): “Perché non ce l’hanno fatta? Riflettendo sugli operai come classe”, Quaderni di sociologia, 17: 19-40.

AMATORI, F. (1992), “Donegani, Guido”, Dizionario biografico degli italiani, 41, http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/guido-donegani_%28Dizionario-Biografico%29/

ARISI ROTA,F. & VIGHI,L. (1973): “I giacimenti di ligniti di Ribolla e di Baccinello-Cana”, La Toscana Meridionale, fascicolo speciale del volume XXVII dei Rendiconti della Società Italiana di Mineralogia e Petrologia, 3.

BARCA,L. et al. (1975): I comunisti e l’economia italiana 1944-1974, Bari, De Donato.

BARDINI, C. (1997): “Without Coal in the Age of Steam: A Factor-Endowment Explanation of the Italian Industrial Lag Before World War I”, The Journal of Economic History, 57 (3): 633-653.

BARDINI, C. (1998): Senza carbone nell’età del vapore: gli inizi dell’industrializzazione italiana, Milano, B.Mondadori.

BERTI, S. (ed.) (2012): Crisi, rinascita, ricostruzione. Giuseppe Di Vittorio e il piano del lavoro (1949-50), Roma, Donzelli.

BIANCIARDI, L. (1962): La vita agra, Milano, Rizzoli.

BIANCIARDI, L. & CASSOLA, C. (1956): I minatori della Maremma, Bari, Laterza.

BOTTIGLIERI, B. (1990): “Una grande impresa chimica tra stato e mercato: la Montecatini degli anni ’50”, in F. Amatori an B. Bezza et al., Montecatini 1888-1966. Capitoli di storia di una grande impresa, Bologna, Il Mulino: 309-355.

BRIANTA, D. (2007): Europa mineraria, Milano, Angeli.

CACIAGLI, M. (2011): “Subculture politiche territoriali o geografia elettorale?”, Societàmutamentopolitica, 2 (3): 95-104.

CAMERA DEL LAVORO PROVINCIALE (ed.) (1950): Il piano economico della Cgil per lo sviluppo della provincia di Grosseto, Grosseto.

CARLOTTI, D. (1865): Statistica della provincia di Grosseto, Firenze, Barbera.

CASTRONOVO, V. (1975): La storia economica, in V. Castronovo et al., Storia d’Italia. Dall’Unità a oggi, 4*, Torino, Einaudi: 1-506.

CASTRONOVO, V. (1980): L’industria italiana dall’ottocento a oggi, Milano, Mondadori.

CGIL (ed.) (1954): Le responsabilità della Montecatini nel disastro minerario di Ribolla, Roma.

CHIESI, A.M. (1998): “Le specificità della terziarizzazione in Italia. Un’analisi delle differenze territoriali della struttura occupazionale”, Quaderni di sociologia, 17: 41-64.

CHIAMPARINO, S. (1976): Le ristrutturazioni industriali, in A. Accornero et al., Problemi del movimento sindacale in Italia 1943-1973, Milano, Feltrinelli: 469-494.

CIUFFOLETTI, Z. (1989): “La Maremma in una storia di lunga durata”, in ISTITUTO ALCIDE CERVI, La Maremma grossetana tra il ‘700 e il ‘900, II, Città di Castello, Labirinto: 7-38.

COLOMBO, U. (1991): “Italia: energia (1860-1988)”, in A. Dewerpe et al., Storia dell’economia italiana, III, Torino, Einaudi: 145-162.

CRIMENI, F. (1997): “I Donegani. Una famiglia del primo capitalismo italiano”, Studi Storici, 38(2), 383-429. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20566829

DEL PANTA, L. (1989): “La popolazione della Maremma nell’Ottocento preunitario: regime demografico naturale, mobilità temporanea e ripopolamento”, in ISTITUTO ALCIDE CERVI, La Maremma grossetana tra il ‘700 e il ‘900, II, Città di Castello, Labirinto: 65-104.

FEDERICO, G. et al. (2011): Il commercio estero italiano (1862-1950), Bari, Laterza.

FIORANI, M. (2005): “Il processo alla Montecatini”, in M. Fiorani and I. Tognarini (eds.), Ribolla. Una miniera, una comunità nel XX secolo. La storia e la tragedia, Arcidosso, Effigi: 129 -161.

FLORIDIA, A. (2010): Le subculture politiche territoriali: tramonto, sopravvivenza, o trasformazione? Note e riflessioni sul caso della Toscana. http://www.sisp.it/files/papers/2010/antonio-floridia-565.pdf

GERBELLA, L. (1948a): Arte mineraria, 1, Milano, Hoepli.

GERBELLA, L. (1948b): Arte mineraria, 2, Milano, Hoepli.

LANZARDO, L. (1976): “I Consigli di gestione nella strategia della collaborazione”, in A. Accornero et al., Problemi del movimento sindacale in Italia 1943-1973, Milano, Feltrinelli: 325-365.

LONGO, L. (1951): “L’agitazione degli operai minatori, un esempio di azione politica e sindacale”, Rinascita, 7.

MATALONI, A. (2006): Le miniere tradizionali delle Colline metallifere, Roccastrada, Ed.Il mio amico.

MESSINA, G. (1948): Carbone, Enciclopedia italiana, https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/carbone_res-661c8dd3-87e5-11dc-8e9d-0016357eee51_%28Enciclopedia-Italiana%29/

MORI, G. (1986): “La Toscana e le Toscane”, in G. Mori (ed.), Storia d’Italia. Le regioni dall’Unità a oggi. La Toscana, Torino, Einaudi:247-342.

MUGNAI, R. (1992): Il brigantaggio in Maremma tra ottocento e novecento, Edizioni Assoprima, Grosseto.

PALAZZESI, M. (1983): Ribolla, storia di un villaggio minerario, Il leccio, Siena.