Revista Internacional de Ciencias Sociales, 43/2022

Social and environmental effects of mining in Southern Europe (pp. 83-100)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.6018/areas.476241

The Ore is Gone, but the Silicosis Remains: Mining Health and Risk Perception in Portugal in first half of the 20th Century

Paulo E. Guimarães

University of Évora (Portugal)

Abstract

The pattern of health risk perception among Portuguese mineworkers changed during the twentieth century, as did forms of state intervention and risk management. Up to the mid-20th century, mining accidents, risks and the need for sickness assistance promoted different healthcare models. Mining companies offered medical and pharmaceutical assistance, and, during the First Republic, the state introduced compulsory social insurance and other labour legislation. The health assistance offered by trade unions was integrated into the general health system during New State (1934–74). From the 1950s on, the legal struggle for recognition of silicosis as a debilitating occupational disease made mine owners accountable. This paper traces this historical experience, the significant path leading to the institutionalization of occupational medicine, health systems and social support in Portugal.

Keywords

Health Insurance; Government Policy, Public Health; Nonwage Labor Costs

JEL codes: I13, I14, J32

EL MINERAL SE HA IDO, PERO LA SILICOSIS PERMANECE: SALUD MINERA Y PERCEPCIÓN DE RIESGO EN PORTUGAL EN LA PRIMERA MITAD DEL SIGLO XX

Resumen

El patrón de percepción del riesgo para la salud entre los mineros portugueses cambió durante el siglo XX, al igual que las formas de intervención estatal y gestión del riesgo. Hasta mediados del siglo XX, los accidentes mineros, los riesgos y la necesidad de asistencia por enfermedad impulsaron diferentes modelos de salud. Las empresas mineras ofrecieron asistencia médica y farmacéutica y, durante la Primera República, el estado introdujo el Seguro Social Obligatorio y otras leyes laborales. La asistencia sanitaria ofrecida por los sindicatos se integró en el sistema general de salud durante el Estado Novo (1934-1974). De la década de 1950, la lucha legal por el reconocimiento de la silicosis como una enfermedad ocupacional debilitante hizo que los propietarios de las minas fueran responsables. Este artículo traza esta experiencia histórica, el camino significativo que conduce a la institucionalización de la medicina del trabajo, los sistemas de salud y el apoyo social en Portugal.

Palabras clave

Seguro de salud; política gubernamental, salud pública; Costos laborales no salariales

Códigos JEL: I13, I14, J32

Original reception date: April 9, 2021; final version: 8 de marzo de 2022.

Paulo E. Guimarães. CICP - Research Center in Political Science. University of Évora. Colégio do Espírito Santo / Largo dos Colegiais 2 / 7000-803 Évora (Portugal).

Tel.: + 351 266 740 800; E-mail: peg@uevora.pt; ORCID ID: 0000-0002-9893-0614.

The Ore is Gone, but the Silicosis Remains: Mining Health and Risk Perception in Portugal in first half of the 20th Century1

Paulo E. Guimarães

University of Évora (Portugal)

Introduction1

In 1944, the development of coal mining near Rio Maior was met with enthusiasm by the local bourgeoisie for the business opportunity it offered; however, there were concerns about the ability of existing health services to support the migrant population. The Misericórdia’s hospital was facing closure because of the increasing costs involved in serving the sudden influx of sick people presenting with a variety of illnesses and conditions. The local newspapers noted that the 1,500 newcomers, who were living in miserable and overcrowded huts, stables and rented rooms that lacked even basic hygiene, air or light. The lack of resources led the Misericórdia to begin refusing to treat those workers, despite knowing they had nowhere else to go. However, the rural population, mobilized by local elites, saved the situation that winter (Rocha, 2010: 225). The next year, the director of the mine established a company medical post that would offer assistance to its employees and their families. He also helped the Misericórdia establish a separate building for treating those with highly contagious and life-threatening illnesses. The company also supported the creation of a cooperative for its employees and set up a childcare centre at the Rio Maior Casa do Povo (People’s House) that would offer pregnant women and new mother’s appropriate medicines and food.

Despite the economic context of the time and the authoritarian social and institutional environment of the history of mining in Rio Maior, the early involvement of the company Empresa Industrial Carbonífera e Electrotécnica, Limitada (EICEL) in the provision, support and control of health and welfare institutions has been labelled industrial paternalism (Rocha, 2010:70-72; Bertaux, 1977; Reid, 1985; Ackers, 1998). It emphasizes the environmental stress and changes that the development of mining brought to rural areas that compelled companies to act and highlights the neglect and resistance to recognizing and dealing with the social costs of industrial illness, accidents, and disabilities. Historical narratives of paternalist initiatives and official discourse tend to undermine efforts to control or suppress emerging forms of bottom-up and democratic mutual aid organizations and their relationship with unions and workers’ struggles. This paper seeks to fill this gap by presenting two cases of the interplay between bottom-up mutual support initiatives along the lines of social solidarity and state-sponsored welfare institutions between the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The first case, in Aljustrel in southern Portugal, we show how mutual aid societies became tools for the mine owners to manage union initiatives and labour and social costs during the early 1930s. The second focuses on a large pyrites mine in the Alentejo (São Domingos) and highlights how during the New State dictatorship the union played a central role in minimizing the effect of famines during the early 1940s. Friendly societies existed alongside the health paternalism of the mine’s British owners, while the creation of a mutual aid society in 1930 was linked to anarcho-syndicalism militancy. Following the fascist state’s social policy, company-based social security funds (Caixas de Previdência) were established that integrated the existing health infrastructure, offered child support, and reduced sickness benefits. Finally, we highlight the central role played by this experience in the late arrival of industrial healthcare in Portugal, which did not appear until the late-1950s, through an analysis of the institutionalization of silicosis as a ‘national issue’ and occupational disease. The conclusion emphasizes the troubled evolution of healthcare provision in Portugal prior to the 1974 Carnation Revolution and how it affected social perceptions of health risk.

The relationship between industrialization, the growth of mutual aid societies and trade unions in providing health services, unemployment insurance schemes and better wages in the earlier period has been described in other European contexts (Harris & Bridgen, 2007; Van Leeuween, 1997). Despite compulsory insurance becoming an important and profitable private business, it was acknowledged that the construction of state welfare in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands weakened the position of trade unions in the provision of such services (Van Leeuween, 1997: 789). However, the creation of the ‘welfare state’ in the UK after the Second World War was an essential part of a vast Labour Party social programme based on ‘state economic intervention’, which explains the centrality of politics in determining its scope (Whiteside, 1996: 102-103). From this perspective, the longevity of the authoritarian regime and its social policies in Portugal during a period of mining and industrial growth contrasts with other European contexts after the 1920s.

Although focusing on the conflictual process that was the construction of health and social security institutions controlled by the state during the first half of the 20th century in Portugal, this article aims to contribute to the new perspectives on labour environmental history that considers industrialization as a social process of the creation of new work environments and their relationship with health and risk and the creation of new concepts, scientific knowledge and social discourses (Sellers, 1997; Nash, 2014; Raihnhorn & Bluma, 2015; Pérez-Cebada, 2020). The focus on the mining sickness and medical aid will show that the dangers of the mining work environment was recognised by the workers long before they were considered as such by doctors and managers in Portugal. The ‘silicosis pandemic’ emerges as a managerial issue in the context of mining modernization and emigration.

State of the art: Sources and methodology

Since the first historical studies on mining and labour organization in southern Portugal were published during the late-1980s, a number of monographs have appeared in the fields of anthropology, history, and heritage studies (see for instance Guimarães, 1989, 2001; Alves, 1997; Rocha, 1997, 2010; Vieira, 2011; Nunes, 2005; Fonseca, 2005; Rodrigues, 2005, 2013; Custódio, 2013). While we have shown how health assistance was embedded within modern industrial organizations and in emerging forms of class solidarity, until recently health and accidents have been almost entirely ignored (Rocha, 1997; Guimarães, 2001:189-197, 278-295; Bento, 2017; Fidalgo, 2018). The struggle of workers at the uranium mine to receive compensation for the damage to their health followed the recent proliferation of studies on the impact of the legacy of abandoned mines (see for instance Gonçalves, 2012; Ferreira, 2012; Veiga, 2014). At the same time, Portuguese historiography has belatedly ‘discovered’ and critically evaluated the labour and social policies promoted by governments during the First Republic (1910–26) and the Estado Novo (1933–74) (Patriarca, 1995; Pereira, 2010; Pimentel, 2016; Almeida, 2017; Garrido et. al., 2017). Most adopt a privileged and institutional approach by examining the legislation, government reports and official journals. On the other hand, the plentiful historical literature on Portuguese mutual aid societies since the 19th century is commemorative, based on quantitative data and legal documents or is described as part of labour organizations (Goodolphim, 1876; Enciclopédia, 1957; Rosendo, 1996). While since the 1930s, the defenders of mutualism attempted to demonstrate their social value by confronting the neglect by the fascists, those who constructed company social security schemes them as a major result of the nationalist state. The construction of an incomplete welfare state following the 1974 Carnation Revolution was almost synchronous with the neoliberal attempts since the 1980s to demolish them in ‘civilized Europe’. Portugal’s historiography is separate from the efforts by historians to set state ‘welfarism’ within civil society and based on solidarity practices that were embedded in labour struggles and institutions.

Our analysis has focused mainly on two mining contexts and has sought to capture the environmental changes caused by large mining interests and health provision by using historical documents stored in municipal archives, and in the local and labour movement press. Extensive analysis of the records of Montepio Mineiro in Aljustrel (medical records, pharmaceutical inventories, management reports) has highlighted the social dimensions of free medical and pharmaceutical support and of the sickness benefits paid by mutual associations that were obscured by subsequent fascist policies and claimed by the defenders of free social organizations. Nevertheless, because they were often unable to pay the monthly dues, many workers were often frustrated and unable to access the support precisely when they needed it most. Mutual societies were not immune to economic crises, the vagaries of the mining industry or unemployment, and the support they could offer was often lower than advertised.

Unfortunately, the medical appointment series is incomplete, and we were unable to uncover similar records for São Domingos. That said, however, they were sufficient to suggest a close relationship with a harsh and unhealthy environment. The archives of the Aljustrel miners’ union (Sindicato dos Trabalhadores da Industria Mineira) revealed important details on the relationship between unions, mutual aid societies and, later, company welfare funds. They confirm the process of conflict involved in cross-referencing competing models of health and social assistance and how fascist social policies were applied.

Here it was not our intention to analyse mining diseases, accident indices and their relationship with technology, scale, and labour safety, and nor was it our intent to examine social responsibility and social costs. We sought to present, in detail, the evolution of health and social assistance as viewed from within trade unions and local schemes, emphasizing the importance of the legal framework and the level of state control across three political regimes (constitutional monarchy, republic and Estado Novo). It was also important to consider income levels and the unbalanced structure of the mining sector compared to other contexts. Analysis by the ministry of labour in the late 1920s states that 70–80% of a worker’s income was spent on food and that the number of calories consumed was far below that of their French and British peers (Grilo, 1924). Alcohol consumption provided Portuguese workers with ‘fake calories’ and gave miners the courage to do their job. Alcoholism was a safety issue even at the beginning of the century in the Panasqueira mines (Gonçalves, 2012). Yet, despite their low income, forms of mutual support on health and death matters did develop in situations of extreme economic and political adversity, and clandestine friendly societies remained in existence right up until the 1960s (Bento, 2013).

The matter of company responsibility for accidents and for the health of their employees has been a matter of intense political debate ever since the end of the 19th century. Our focus on the late emergence of silicosis is based largely on literature produced by doctors and engineers, parliamentary debates, and legislation. We demonstrate how this risk was managed in the public sphere and the measures taken, and not avoiding the difficulties faced in the recruitment of workers. Finally, we reflect on the different assistance schemes in this universe during the 20th century and how the health risk perception has been shaped by inequalities of social power and political constraints.

Environment, social change, and response in mining contexts

In the Alentejo as elsewhere in Portugal, the environmental impact of a large mining industry in a rural milieu during the first stage of its life-cycle was caused mainly by demographic pressure. The sudden population growth drove up the price of goods, housing, and services. Most of the newcomers were male and mobile. It became increasingly difficult for the two communities to live together.

The mines first attract vagrants, malteses, who were predominantly males, poor local labourers and craft workers, who huddled together in bedrooms, houses and in huts on the outskirts of the town. In the Aljustrel, São João e Algares mines, most of the mineworkers came from the Algarve, where they had worked in mines like the São Domingos, near the River Guadiana, and from Spanish border towns and villages with mines, such as Paimogo, and from the impoverished Alentejo and Algarve highlands (Guimarães, 1989, 2001).

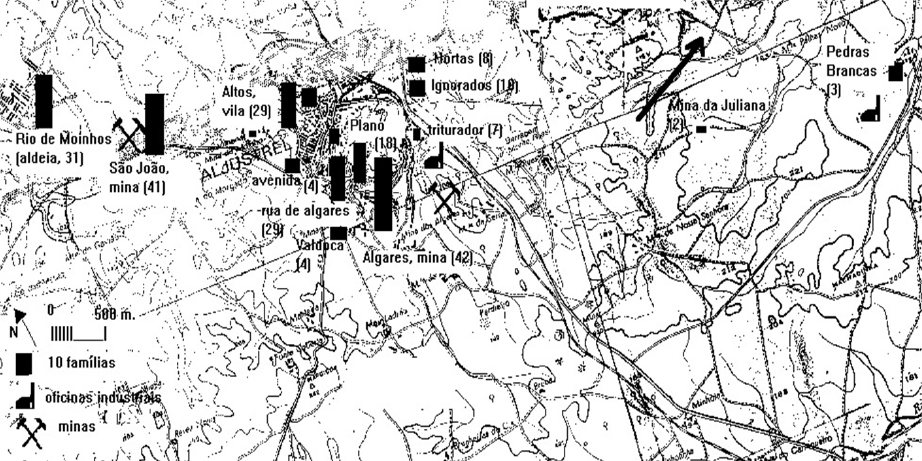

The two mines being studied had been in production since the 1860s. The first was leased from La Sabina by the British company Mason & Barry Ltd, while the second only resumed operations under a concession agreement with the Société Anonyme Belge des Mines d’Aljustrel (SABMA) in 1898 after its previous operator, Companhia de Mineração Transtagana, went out of business in 1885. This Portuguese-Belgian company rented some properties in the area and built some more during the 1950s. In Aljustrel, São João, Cú do Lobo (near the mine of São João) and Algares neighbourhoods in the outskirts of the village mark the extent of the mine before it expanded during the early decades of the new century into the Altos and Aldeia das Magras districts (Map 1). The population of the parish almost doubled by 1911 when it stood at 6,570 before continuing to rise to almost 9,400 in 1940.

During the 1920s, new neighbourhoods expanded the urban network bordering the local miners’ union building. Each neighbourhood was a micro-universe, and the rivalry between them was often violent. In September 1902, a blood crime by a Spanish miner gave rise to this rivalry that resulted in them suffering grievances under futile pretexts. The government delegate called in the army at a time tempers were running high (Aljustrel, 1902). The army was regularly called in whenever groups concentrated (e.g. at annual fairs and festivals), and social tensions foreshadowed threats to public order. As in other industrialized areas in Portugal, the mining areas were militarized with detachments from the Republican Guard being stationed in them after the 1910 Republican Revolution.

The sudden influx of people and animals that concentrated in and around the mines put enormous pressure on already limited health services. Augusto Montenegro’s (1829–1908) 1902 ‘hygiene survey’ of Portuguese cities and towns showed that like other villages in the region, Aljustrel had no sewerage system and that human and animal waste was accumulating around the periphery. Urban growth exacerbated this problem in the spaces where men and animals lived together. Montenegro found “many stables near houses that, due to the lack of cleanliness, contribute to poor health”. The situation was made worse by the “large number of people living in the same house because the itinerant mining population is large” (Montenegro, 1903). He advocated resolving this problem by adhering to “municipal positions”, and “expanding working-class neighbourhoods”. The health threats included a stream surrounding the village that was filled with stagnant water, something that was fairly typical in that region in the period from late summer to autumn. The fact he found no bacteria in the waters led him to state that the village’s water supply was of good quality, despite the presence of “limestone and rust”.

According to the local press, epidemics were relatively frequent and localized before 1920. In May 1897, an outbreak of smallpox was reported in Aljustrel and an outbreak of typhoid fever in the São Domingos mine (Bejense, 22 and 29 May 1897). In 1901, a measles outbreak in Aljustrel led the county administrator to force the mine owner to demolish “the primitive shacks” housing itinerant workers near the mine. The residents of the São João do Deserto and Algares neighbourhoods on the outskirts of the village were forced to whitewash the properties they rented from the company.

The village hosting the São Domingos mine and others nearby (Corte Pinto, Santana de Cambas) suffered from similar “structural” problems. During the 1950s, drinking water was drawn from wells dating from 1869, there was no sewerage system or running water and overcrowding was the norm right up until the mine closed in 1965. Household waste was removed by cart, and public cleansing was limited (Castro, 1986). Disease ruled community life in both villages. In September 1904, a religious festival in honour of Saint Sebastian, and which involved the local music society, which was sponsored by Mason & Barry, celebrated the end of the smallpox epidemic that had affected both the mine and the mining towns for six months2. Aljustrel experienced a six-month smallpox epidemic in 1915 and was struck by the Spanish flu in 1919, which swept through a community that was malnourished as a result of unemployment and price speculation.

The authorities compared the morbidity in mining areas to the so-called ‘cemetery’ urban spaces that housed the urban proletariat in Lisbon’s villas, Porto’s islands and all other industrial cities throughout Europe. Malaria (‘intermittent fevers of bad character’) was endemic, while ‘national major diseases’ such as tuberculosis and sexually transmitted diseases affecting the adult population added to them, made worse by working conditions. None of ‘diseases’ that directly affected miners, such as pneumoconiosis, was recognized as a health issue until the end of the 1950s.

To assist Aljustrel’s new mining population, at the beginning of the 20th century the municipality had a Misericórdia, a private institution established in the seventeenth century. According to its 1912 charter, its Christian obligations were to offer alms to invalids and indigents, food and medication to the poor and sick in their houses and medical assistance in its hospital (Misericórdia, 1913, art. 16). To become a member, one needed to be of ‘good moral and civic behaviour’, have basic schooling and be proposed and accepted by the board of directors. The 103 ‘brothers’ were dominated by local aristocrats, landowners, traders and businessmen. Until the republican takeover, the Misericórdia spent most of its resources on religious worship. The hospital was also supported by the municipality to the extent of its limited ability, although the local authority was unable to meet demand from the mine. Revenues from levies on the mines were insufficient and generally allocated elsewhere, meaning access to health care remained problematic for individuals and for mine owners looking for a continuous supply of labour.

The first mutual aid society was established in 1893 by republicans who recruited members from the middle class, small industrialists, traders, and workers (Montepio, 1904). Among the founding members were the republican physician Manuel Joaquim Brando (1869–1934) and Joaquim Brito Camacho, future mayor of Aljustrel and brother of Manuel Brito Camacho (1862-1934), one of the leaders of the republican party. They were also leading lights in the local republican centre that offered free schooling to adult workers. It offered its members free medical consultations and a sickness allowance. To become a member, candidates had to be under the age of 45, have an ‘honest’ regular income and be in good health. The membership fee was 1,200 reis, then 200 reis a month. The society’s sickness allowance was 120 reis a day for the first six months, thereafter 100 reis a day for three months. There were no literacy restrictions, but the highly irregular and low income received by most non-skilled workers at the time certainly limited their opportunities for membership. The existence of ‘honorary’ membership meant it was a secular charity ‘above religious or ideological affections’ that was intended to fill the gap that existed between what the Misericórdia provided and social needs.

The mutual society Mineira Aljustrelense (Montepio Mineiro) was established in March 1906 by the mining ‘communities of São João e Algares’. Its goals were similar: to provide free medical and pharmacy assistance and sickness allowance, and to help with funeral costs and offer support to widows. Women were allowed to join as long as they met the conditions: be between 15 and 55, be in good health (following an examination) and work in the mines. Membership cost 1,000 reis then 400 reis – or an average day’s pay for a miner – per month3. Health benefits covered family members and dependents under the same roof (Associação, 1907, art.º 18, n. 7). People could be expelled for fraud and benefits were suspended if the member fell behind in their monthly payments. Despite the ‘democratic principles’, the high rates of illiteracy among male workers (about 60 per cent) limited their participation. In fact, 131 of 244 of the founding members were unable to sign their names in the charter. Of the remainder, 28 were Spanish, Belgian, French and other foreign workers were literate and included skilled workers, foremen and some clerks.

During its first year, the society hired two doctors (Manuel Brando and Joaquim de Almeida) and a clerk who oversaw the payment of allowances through regular home visits. Annual reports for the following years show that large numbers of people dropped because of difficulties paying the monthly dues. They also note the difficulty the society had in recruiting new mineworkers4. The active involvement of the society’s Belgian director, Victorian Volpélière, was noticeable from 1909 when he played a key role in the society’s future by renting a building for pharmacist, administration and medical appointments, and then providing it with furniture, utensils and paying the fines and penalties that were due at times of industrial unrest. To help mitigate any possible liquidity crises in the near future, Volpélière banned senior staff, who were also society members, from receiving medication and allowances. Foremen were then called to punish those workers who had been reluctant to join the society by giving them the worst jobs (Mourão, 1911). The presence in the board of qualified mining engineers, like Maurice Stass, and highly-qualified employees reinforces the link with the management of the mines. Despite such offers in kind, in 1913, 93 per cent of the society’s annual income came from monthly dues, while fines made up less than 1 per cent. Moreover, its money was deposited in banks and received shares in the capital of SABMA. The society, therefore, became a tool for rational and efficient workforce recruitment and management away from labour militancy.

The Montepio Mineiro was effective in providing sickness support to those working in different mining departments and their families. However, the support soon ceased to be egalitarian. In August 1910, the annual general meeting established three classes of membership, with new members now having to pay half the cost of the medication. Sons earning a daily wage of at least 300 reis were no longer regarded as dependents, with the member having to continue paying fees even when out of work and receiving sickness allowances. A third-class member paid just 200 reis, half the first-class due, but received half the allowances. Some types of injuries were no longer covered, such as those resulting from fights, drunkenness or matters of ‘public disorder’ (Associação, 1909; Guimarães, 2011:192).

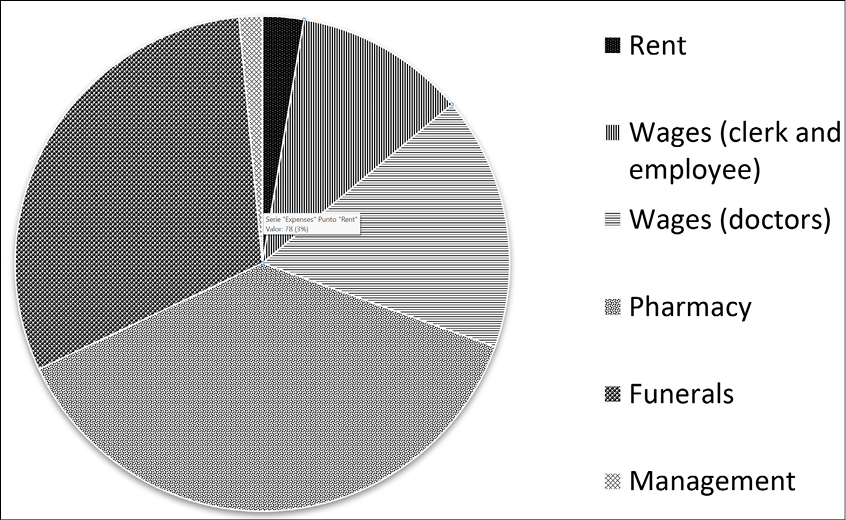

Annual reports reveal the extensive use of pharmacy services (graph 1). At the beginning of 1910, the society had 494 members and almost 800 receiving medication. Membership mobility was high and mirrored the mobility of workers in this industry: 18% stopped paying dues, 11 died and nine became inactive. However, there were 192 new admissions who received few benefits (Associação, 1910). The documentation allows us to capture the demand for medical services between 1911 and 1914 when 8,596 medical appointments were made by two doctors over 36 incomplete months. Considering that there were on average 1,000-1,200 day workers, we can conclude that access to free health care was effective and most probably fast. Moreover, this assistance covered the closest family member resident in the village. Consequently, 42% of medical consultations were for members’ children and 21% for wives and widows. The mothers and brothers of unmarried members were also eligible for assistance, although this number is not very significant (104 appointments, see Table 1).

Table 1. Distribution of average medical appointments by mutual society members and their dependents

|

Year |

Member |

Daughter |

Son |

Sister |

Brother |

Wife |

Mother |

Not mentioned |

|

1911 * |

251 |

80 |

176 |

1 |

0 |

135 |

4 |

3 |

|

1912 |

942 |

155 |

1026 |

13 |

14 |

514 |

22 |

11 |

|

1913 |

1,006 |

390 |

984 |

5 |

9 |

652 |

10 |

18 |

|

1914 ** |

842 |

237 |

577 |

2 |

8 |

526 |

15 |

9 |

Source: see Table 3.

* 2 months ** 10 months

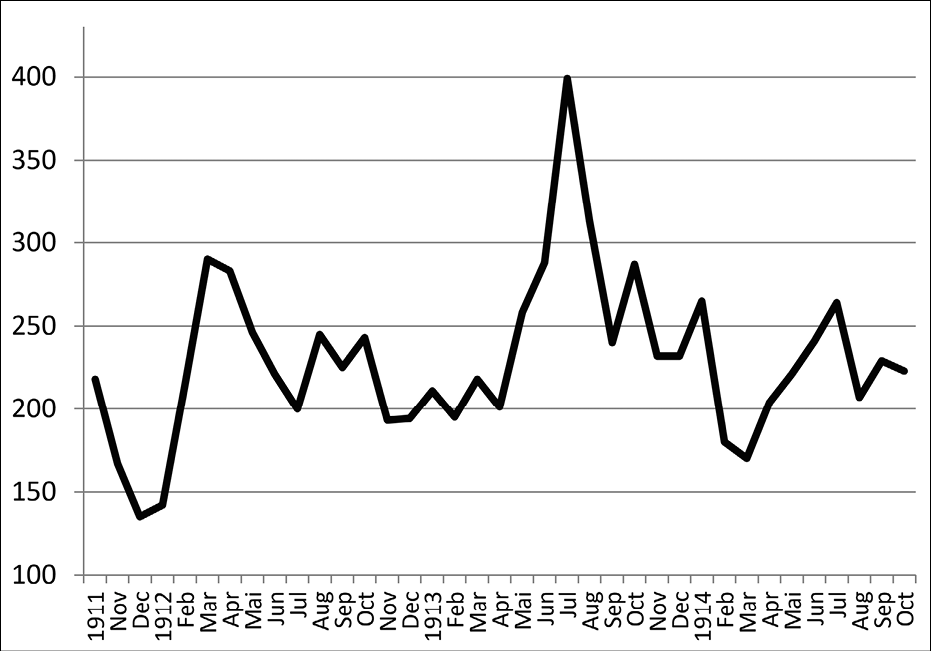

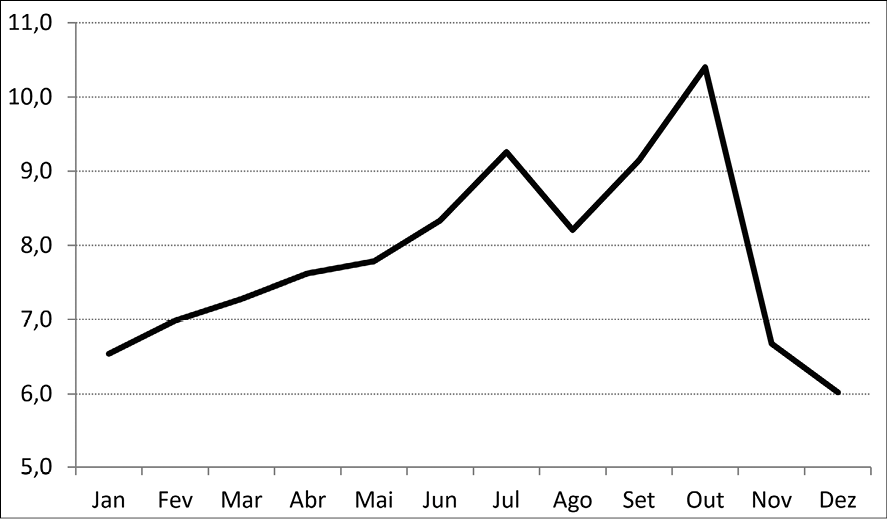

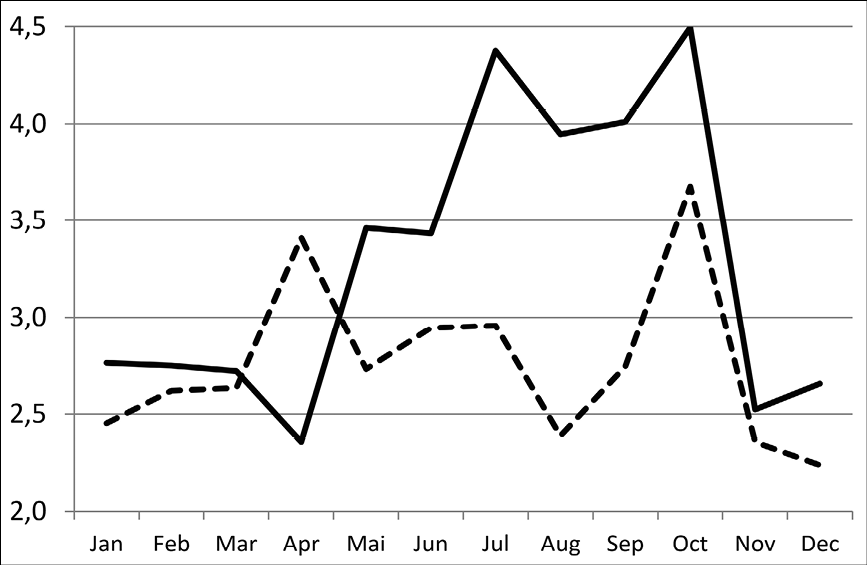

More than 3,000 of the doctors’ appointments (35%) were made by workers. This means workers and their families made extensive use of the medical assistance, despite it being generally seen as a last resort. However, the data show significant monthly variations in medical appointments (standard deviation 49.3) with peaks in March 1912 (290 consultations), June 1913 (399 consultations) and July 1913 (Graph 2). The size of the sample does not allow us to find any trend over time, but we can see seasonal patterns (Graph 3). Between late autumn and late winter, the need for medical aid was lower (average of 6 to 7 daily appointments per month). During spring, the number of appointments gradually increases until July, then it falls in August before rising again until the critical month of October. This suggests the incidence of infectious diseases such as dysentery, malaria, cholera and influenza within populations living in poor hygienic conditions, overcrowded houses and suffering from malnutrition rather than a random pattern generated by male industrial accidents and diseases. In fact, this pattern changes when we disentangle the adult population data (Montepio members were mostly male mineworkers) from that of their children (Graph 4). Here we find that for children, late spring, early summer and the months of September and October were the most challenging. In the case of adults, the use of medical aid does not have the same intensity, although October was also the most difficult. The biggest difference is during the typically wet month of April, which is bad for adults but best for children.

Table 2. Frequency of medical appointments by seniority at Montepio Mineiro, Aljustrel, 1911-1914.

|

Members number |

Medical appointments |

Average per member |

|

[001-100] |

340 |

11.3 |

|

[101-200] |

362 |

12.0 |

|

[201-300] |

263 |

8.7 |

|

[301-400] |

218 |

7.2 |

|

[401-500] |

375 |

12.4 |

|

[501-600] |

221 |

7.3 |

|

[601-700] |

101 |

3.3 |

|

[701-800] |

361 |

12.0 |

|

[801-900] |

278 |

9.2 |

|

[901-1000] |

37 |

1.2 |

|

[1001-1100] |

274 |

9.1 |

|

[1101-1200] |

189 |

6.3 |

|

Total |

3,019 |

2.5 |

Sources: see table 3.

The distribution of patients across the mining territory reveals the incidence of disease within both the mining districts and the village as a whole (49 streets, squares and neighbourhoods) where most of the society’s members and employees lived. Central Street provided the majority of patients (832 medical records), followed by Oriental Street (761) and Retiro Street (686). Then follows the mining neighbourhoods and the outskirts: São João (776), Algares (587), Valdoca (538), Altos (295) (cf. map 1). Our data suggest health care provision was greater for those who had joined the society earlier (51.6% up to membership number 500, compared to 33.1% for members 501-1000) (see map 1 and table 2). These figures are even higher when considering those who left the society in 1914. In any case, only 28.5% of patients had one medical appointment in three years, 39% had two to five appointments and 32.1% had more than five (see table 3). This suggests the presence of people with chronic ill-health, recurrent illnesses and suffering the long-term effects of injury. Significantly, 14% (86) of patients saw the doctor more than ten times in three years. These figures are reinforced by similar medical care demand patterns by the sons of workers, with the difference that the relative frequency of patients with 11-20 medical appointments was much greater (Table 3). This contrasts with female behaviour: the number of doctor appointments made by daughters was almost half as much as that for sons (298 compared to 427) and the number who attended six or more times is also much lower, with none having more than ten consultations. This can be explained by the different kind of work women carried out in mining communities: while sons often followed their fathers in the mines, where they experienced the same harsh and dangerous environment, women generally did the less dangerous work of breaking and picking minerals or as domestic servants. The general picture emerging from the Montepio’s doctors’ appointment books is that the use of health services was high despite the relatively young population.

Mutual aid societies, labour solidarity and the fascist state

The growth of mutual aid societies in Portugal after the 1850s was associated with the growth of the wage system, urbanization, economic growth and bureaucratization. In 1883, there were 295 mutual societies across the country (mainly in Lisbon, Porto, Setúbal and Faro), with 94,200 members and at least 400,000 beneficiaries (Goodolphim, 1876; Rosendo, 1996: 632-643). They were allowed to operate under a system of king’s charters (alvarás). Social legislation introduced in 1891 created the general conditions for the grown of mutual societies as part of the intention to create the conditions for the harmonious development of industry by establishing a government-controlled institutional framework for the provision of medical assistance, funeral subsidies, and accident and pension funds for workers and their families. Many charity institutes that promoted individual charity based on the ‘deservedness’ of the receiver in the eye of the giver, often based on Christian values, fiercely opposed the mutual societies and sought to limit their ability to offer support. Conservative elites tended to defend individual charity, the system of misericórdias and private charitable institutions against the expansion of mutual society protection favoured by the Republic (Grilo, 1926). A decree published on 2 October 1896 banned mutual societies from offering long-term invalidity and survivor pensions. They were also prohibited from operating pharmacies or arranging special contracts with drug suppliers. To ensure their economic viability, the minimum number of members the societies required significantly increased depending on the importance of the municipality, reaching as high as 500 in Lisbon and Porto.

Mutual aid societies were important in mining communities, given most were small and short-lived. They existed in larger operations, including the São Pedro da Cova (near Porto), at the Valongo slate quarries and in Aljustrel; however, at São Domingos, which was the largest mine, it was not until the 1930s that the British owners allowed space for the mutual societies. Mining paternalism had been a reality since the 1860s with the company building and funding the local Catholic church, school, hospital, market, consumer cooperative, music society and theatre and, from the 1920s, the local football club. As in other mines, fines levied on workers who broke discipline were paid into an accident fund. The mine hospital and doctor cared for sick employees and their families, with those seriously injured in mining accidents sent to Lisbon when necessary with the costs being met by the company. As in Aljustrel, local hospitals provided ongoing treatment, dealt with minor injuries and delivered first aid in the event of accidents.

The economic instability resulting from war and inflation placed the societies under pressure. After the First World War ended, republican governments funded both the misericórdias and montepios struggling with the rising costs of drugs and health services the provided (Grilo, 1926). However, the Military Dictatorship and New State were hostile to this republican development. This led to the reform of 1931 (decree 19.281 of 29 January), which doubled the number of people required to establish a society, enabled mergers, limited the social benefits provided, prevented the private companies from supporting them and subjected them to close state supervision through the Compulsory Social Insurance and Social Welfare Institute (ISSOPG – Instituto de Seguros Sociais Obrigatórios e Previdência Geral) (Rosendo, 1996: 596–7, 600). Their subordination to the authoritarian state ended the societies’ federalist ideals. In the years of industrial and urban unemployment that followed, permitted social benefits were reduced and membership costs increased, reducing their appeal.

The economic crises of 1930-34 had a profound effect on the lives and conditions of those working in the pyrites mines that had a high dependence on exports. In Aljustrel the mines went on to short time, operating only three or four days a week until 1933, resulting in underemployment, unemployment, and hunger. Facing financial difficulties, at the end of 1931 the mutual aid society was forced to increase its dues, while led to most workers ceasing payments or falling behind. This was the context in which a group of around 30 miners decided to establish a solidarity fund for the poor and the sick (Caixa de Solidariedade aos Doentes Pobres) with a different set of guiding principles within the local trade union (Associação de Classe dos Operários Mineiros de Aljustrel). Members were required to pay one escudo (1$) per week (compared to the 6$ or 3$ demanded by the Montepio), but only when at least one member fell ill5. As with the Montepio, members could receive allowances for up to one year. However, the size of the allowance paid depended on the number of people receiving them, as the common fund was shared between them, something the law prevented mutual societies from doing. In the event of a member’s death, each member was committed to paying the widow 2$. In 1934, allowances no longer covered bicycle racing, bullfighting, football games, drunkenness or venereal diseases, while in cases of ‘disorder’, the board could call a general meeting to make a decision. Mutual aid was disbursed on moral grounds: with a sick worker receiving at least as much as the very least paid to a male mineworker:

All members will receive 5$ each day for up to 365 days. If the member remains ill after one year, the board may decide to make such donations as it sees fit. (Caixa, 1934. Act 3, 5 February)

Solidarity was restricted for exceptional cases. One victim of an accident at work received allowance after a meeting called for that purpose; however, the fund did not usually extend to workplace accidents and the comrade had no insurance. However, it refused to pay a funeral allowance to the family of another member killed in a workplace accident and who had obtained support from the Montepio. The social control aspect was significant: in March 1934, the director of the Caixa suspended one allowance when he discovered a member had attended a dance while off sick. In another case, payments were halted because the member was found working during that period. Improper behaviour, such using inappropriate language at meetings or to the board of directors was reason enough for expulsion.

Regulations were easily changed and depended on the will of the general assembly as it considered proposals, finances and health. One year after opening, the fund decided to accumulate a reserve fund by collecting monthly fees even when no one was receiving payments. By 1937, the fund had more than 60 members and the monthly dues raised to 6$, which was half a day’s pay for a miner. In January, during an epidemic, the daily sickness allowance was reduced from 7$ to 5$. The fund faced a number of complex situations: the number of absent members increased as a consequence of political persecutions and imprisonments, while others left the union. During the January 1939 meeting members held three minutes silence for the missing members. Soon thereafter, all those who did not join the local branch of the fascist National Miners’ Union were expelled by order of the INTPG’s government delegate (Instituto Nacional do Trabalho e Previdência Geral).

The recovery of production in the late 1930s led to a significant increase in the number of industrial accidents. In 1935, the number of injuries in all mining departments was 62% of the average workers per day; in 1937, that figure had risen to 107% (Guimarães, 2011: 293). It was in this context of the rationalization of mining work and of the increase in incidences of silicosis and tuberculosis that the Montepio purchased electrical equipment to help diagnose occupational illnesses and created the conditions for treating workers locally instead of sending them to the capital. The introduction by Montepio of the state’s obligations in 1936 was poorly received, with the monthly fees rising to above what companies paid most of their employees.

The outbreak of war increased long-term unemployment as the mines closed for long periods, forcing the government to intervene in the face of social crises and famine. The union fund closed in 1941 after paying an extraordinary allowance of 5$ to sick members at Christmas. Expenditure was higher than revenue during this ‘age of hunger’. In 1942, miners were sent to dig coal at São Pedro da Cova, about 450km to the north, and to the distant wolfram mines at Panasqueira to others in the centre and interior of the country. A programme of road building was launched to provide employment for starving workers. Studies on workers’ wages by ISSOPG showed they consumed an average of 2,400 calories, 600 of which was through the consumption of wine and a level much below the minimum required for hard physical labour. In 1942, a ministerial decree fixed the wages at a number of mines at pre-war levels to prevent price inflation, in a move that only worsened the situation. Larger foreign companies, such as the one operating at Panasqueira, were concerned with productivity more than with wages and began to provide its employees with food and drinks at the entrance to the mine shaft.

The relationship between anarcho-syndicalist labour organizations and mutual societies can be seen in São Domingos, Mértola, which was the largest mining operation in the country until the late 1930s. The creation of worker-controlled mutual societies became a significant demand of the local miners’ union after 1930. Its aim was to establish a compulsory pensions fund and a mutual society for workers that could absorb the small welfare institutions and health facilities6. The Cambas Mutual Union was founded with 750 members on 29 January 1931 to provide medical assistance, medication and financial support during non-workplace related sicknesses. Of these, 100 came from two existing societies that now merged, A Lutuosa and Solidariedade. The former offered support to pay for funerals, while the latter was linked to the union. However, the government refused this mutual society an operating licence (alvará).

The economic crises in 1932 drove the miners to strike for two weeks. Their dispute was over low wages, mining safety – including calling for the end of the táreas system through which foremen set high productivity targets and imposed wage penalties – a demand for the more physically demanding tasks be performed by those in better physical condition and who had the necessary skills. They also demanded a maximum seven-hour day in the harsh underground environment where there was limited ventilation, dust and heat and 60% pay increase, which they argued was the minimum required for them to maintain their physical condition (Sindicato, 1931). The mine was occupied by the army, which sent in a machine gun company, with the strike committee being forced to flee across the Guadiana into exile in neighbouring Spain.

Despite defeat and the repression following the strike, the União Mutualista das Cambas was established formally in 1937, with no funds with which to face the 1940s economic situation. As in Aljustrel, sickness benefits were below subsistence level, leading to clandestine friendly societies resuming their activities (Bento, 2013). During the late 1940s, according to a social work employee, many societies took the name of the locality in which their members lived (Santana de Cambas, Corte Pinto, Pomarão, etc.) (Jaques, 1947: 142). While forbidden by the fascist authorities, they nonetheless persisted until the mine closed in 1965, offering health benefits and family support when a member died of natural causes. Members only paid fees when another member was either receiving benefits or died. In such cases, someone was chosen to collect the monthly fee. Those receiving sickness benefits were paid 12$-15$ a day, half the amount paid to a miner or locksmith, depending on the size of the group. The rules often changed according to need. With no health and bureaucratic infrastructure to support, they had no permanent overheads: personal ties were the most valuable asset.

There was also a fund for the poor, the Caixa de Auxílio aos Pobres, that in 1946 was based in the police station. Its income depended on the generosity of charitable members and the profits from the company-managed cinema. It disbursed alms to the elderly poor and clothes to the needy sons of miners. The local miners’ union, the Sindicato Nacional dos Operários Mineiros e Ofícios Correlativos do Distrito de Beja, also provided a free Christmas lunch. Legally approved welfare assistance, therefore, remained wholly in the hands of Mason & Barry. Health services were provided by a doctor, a pharmacist, a nurse and midwives to cater for more than 10,000 people. The hospital, which was built in 1875 when mining disasters and deaths were running high, could offer operations and help injured workers and their families. While there was a lazaretto, families preferred to look after their ill at home. More importantly:

the people do not have confidence in the doctor, which is why only after applying all home medicine and blessings, do they appeal to science. He claims the doctor does not listen to the patients, but simply looks at them and hands them a prescription. The problem of health care is what most revolts the population7.

In 1946, Mason & Barry paid retired workers with 35 years’ service a pension worth 50% of their pay: fewer than 10% of the workforce (174 people) were to benefit from it. Those permanently injured as a result of industrial accidents were given jobs suitable for their physical abilities. Following the policies of the New State to encourage childbirth and to the ‘race’, monthly breastfeeding and family allowances were paid (100$ for each birth, 30-40$ breastfeeding allowance and 25-60$, depending on the father’s wage, for the family). The company also encouraged Catholic marriages by offering unmarried couples living together 250$ to get wed.

The war resulted in reduced production at the pyrite mines. While unemployment increased and underemployment became more generalized, shortages of food and goods encouraged speculation and hunger became more widespread. Community kitchens (cozinha económica), which were commonplace during the mining strikes of the 1920s in São Pedro da Cova and Aljustrel and in São Domingos in 1932, sprung up. From 1941, the corporatist union’s annual reports recorded the money given to the community kitchens and the subsidies provided by the Beja civil government as income from members declined. In Christmas 1941, the union distributed food and other goods to workers (about 2.700$, or 112 day’s pay for a miner) and received 2,000$ from the civil government: nowhere near enough to support almost 2,000 workers (Sindicato, 1941). By December 1942, the community kitchens accumulated a debt of 15,000$, while their state-controlled fund stood at 9,800$.

In January 1944, the kitchens paid 1,100$ cash and 1,500$ in credit for supplies, distributed 3,000$ worth of food to the unemployed and donated 2,700$ to the Caixa de Auxílio. The Sociedade Cooperativa Cozinha Económica was formally established in January 1944 and received support from the corporatist union (28,000$ in 1944), from the state (9,000$ from the Welfare Directorate-General to provide assistance to the unemployed and which was channelled through the Beja civil government), with Mason & Barry providing almost 2,000$. The community kitchens purchased rice, potatoes, pasta, peppers, canned sausage, salt, olive oil and soap to make the soup it distributed to all parts of the mine. The soup could be paid for in cash, purchased on credit or donated freely to the unemployed. The government used the unemployment fund created in 1932 to force starving men to work building roads. Medical assistance was required at least once for some workers who were incapable, who also received soup from the community kitchen. The new cooperative used the same books as the company in order to control daily attendance and record credit sales. This is why we know credit sales were widespread among male miners, general service workers and engineers. It was not uncommon for more than one soup per day to be purchased on credit8. The data for 1942 and 1943 show that most bad debtors were actually women.

The New State used the labour and welfare administration established by the First Republic (the Instituto de Seguros Sociais Obrigatórios e Previdência Geral) to force companies to establish social insurance funds. In 1932, a compulsory 2% wage deduction was introduced to establish a national unemployment fund (Fundo de Desemprego). This was opposed by the union, which organized peaceful protests in an attempt to encourage local authorities to repeal the law. In 1936, the creation of local corporatist unions as a result of the 1934 National Labour Statute (Estatuto do Trabalho Nacional, inspired by the fascist Carta del Lavoro) strengthened the practice of making compulsory wage deductions, with all mineworkers having to pay union dues. The creation of the Mason & Barry Personal Welfare Fund in 1946 brought an end to the União Mutualista das Cambas. This was not a popular move as with it the company ceased to meet what had for a long time been considered social obligations, with the benefits provided inferior to those they replaced. Moreover, the new scheme was also more expensive, adding strain to already low take-home pay.

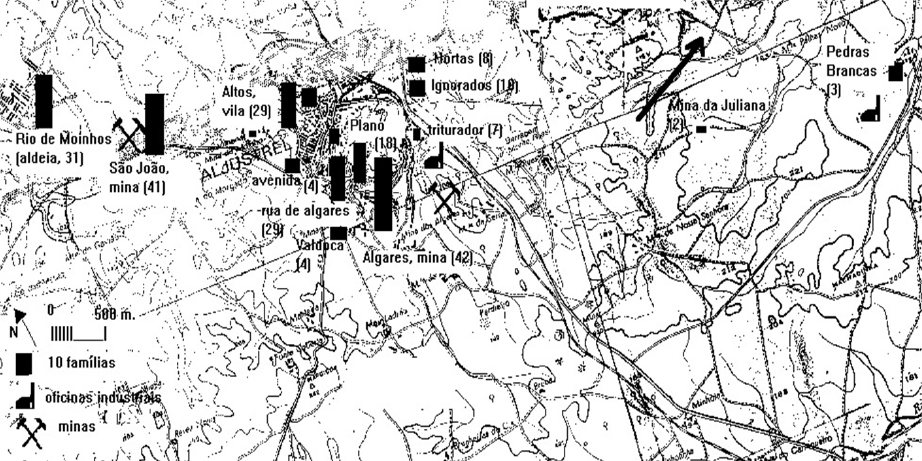

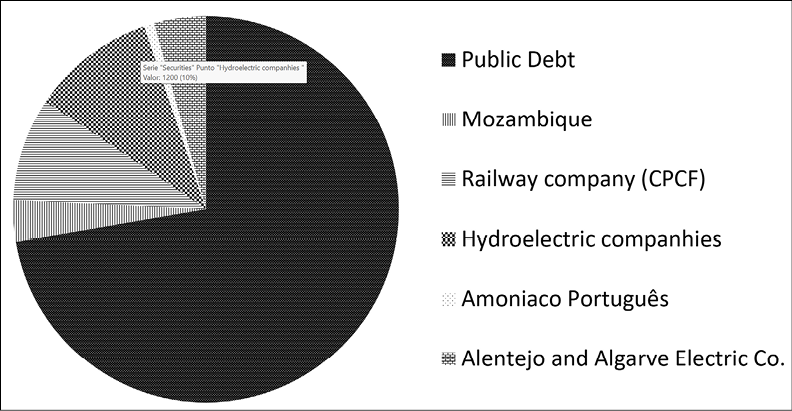

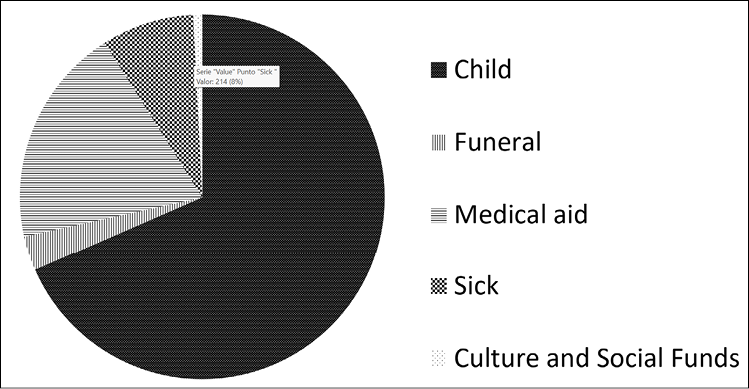

In 1956, the Mason & Barry Welfare Fund employed four clerks and one other, with the majority of its benefit outlay being for family allowances (abonos de família), while sickness allowances cost 68,700$ for illness, 7,600 for this injured in workplace accidents and 1,700 for those with ‘child and family’ (Graph 5). Management expenses (salaries, rents, bureaucracy, transports, etc.) cost 151,800$, while healthcare costs (doctors’ salaries, medicines, transport, etc.) cost 510,300$. The fund also paid for 70 children, from a total of 25,700, to spend time at the Vila Nova de Milfontes holiday camp. The resulting fund reserves (11,900$) were used to service the debt, pay the holiday camp, banks, Portuguese electrification and other projects supported by the government – such as Amoníaco Português (the manufacture of nitrogen fertilizers). In 1960, the fund’s securities amounted to 16,600,000$, which helped fund new government-sponsored capitalist adventures, such as Siderurgia Nacional and Sorefame, by the financial elites to manufacture steel and machine-tools (Caixa de Previdência, 1961). The rapid growth of mining after 1935 was supported by company-based health policies. The 1937 industrial accidents law (Decree 27649 of 12 April) forced companies to provide medical and pharmaceutical first aid to injured workers, transport them to the nearest health centre and appoint a doctor, all at the employer’s expense. Companies were also told to provide local clinics. Far from being a burden on companies, the state was simply confirming the practices already employed by the larger mining companies. Generous post-war legislation on industrial diseases and accidents that updated earlier laws passed by the Republic but which had not been forgotten and not enforced legitimized the establishment of company welfare funds operating under state corporatist rules. Those funds were used to finance capitalist adventures and establish an insurance industry9. The creation of company-based welfare institutions on the same coercive basis was generalized after the war in mining. Despite the absence of government support, mutual societies continued in Aljustrel and Valongo, while in São Domingos clandestine friendly societies continued operating.

Miners’ diseases: From collective representations to the ‘silicosis epidemic’

After a lifetime underground, miners reported suffering from asthma, bronchitis and rheumatism, wrote a female social work officer posted to São Domingos in 1946 (Jaques, 1947). Their sputum was black on account of the mineral dust (tufo) they breathed and swallowed. They quite often died suddenly of congestion: they say they are poisoned and burned inside. However, Mason & Barry’s doctor claimed the ailments were caused by alcoholism. Miner’s ate little, their bodies emaciated and often experienced ‘stomach upsets’. Occasionally one would be sent to Lisbon for stomach surgery and would die or their ailments remain uncured. However, different working environments had different health effects: those who worked in the quarries were no better off than those working in the sulphur factory or down in the galleries of the mine. Because of the political instability after 1936, the British company, which was now part of Rio Tinto, opened a sulphur factory in Achada do Gamo, close to a mine like the one in Huelva, Spain, bringing with it acrid smoke that poisoned the already sparse vegetation.

In 1939, the miners’ union claimed the wages paid to miners were insufficient to feed him and his family. While refusing to increase their pay, managers did give the miners permission to cultivate small pieces of land: a policy that pleased the authorities. In the summer, miners established friendly societies to harvest wheat under contract with farmers and landowners. Children were put to work in the fields and, if they were 15, in the mine. Yet, malnutrition was the rule. The family wage was studied by ISSOPG, which noted that industrial workers in Portugal spent 70-80% of their income on food and had the poorest nutrition of workers from any industrialized country. The miners were so poor that they had to use their mining lamps at home with candles and oil lamps being considered luxuries.

People explained the emaciated condition of the people by saying it was typical of the region. Women were so weak that stillbirths and spontaneous abortions were high, and often they had no milk with which to feed their children. The local doctor claimed the causes were poor diet, constant worry and misery. Pregnant women were ashamed to apply for medical assistance and nursing mothers did not care for it. According to the same source, enteritis was the leading cause of death among children – responsible for 50%. Scrofulosis was also so frequent that it could be treated with a day at the beach, which is something doctors often prescribed.

Head colds were common in winter and, among miners, asthma, bronchitis, rheumatism, congestion and “digestive disorders caused by poor food hygiene” were at the top of the list of local diseases. “Tuberculosis tends to progress as a product of misery, food, hunger, cold and unemployment.” (Jaques, 1947). Working in rags and wearing rope shoes in acidic and humid mines, they often also got open sores and skin diseases. Mechanization also produced neuronal diseases and affected the speech of miners, which was often slurred.

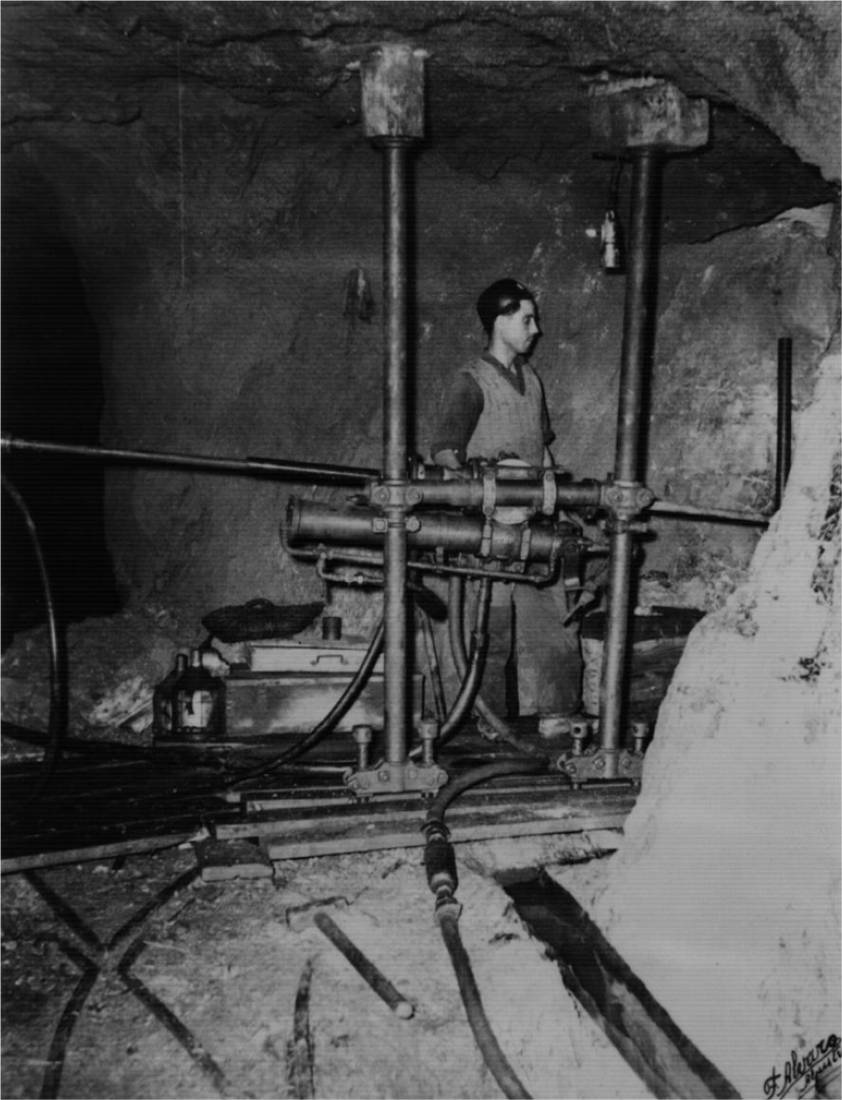

Law 1,942 of 27 July 1936 and Decree 27,649 of 12 April 1937 that made labour insurance virtually compulsory for companies employing more than five people included silicosis in the list of occupational diseases. However, these laws soon became dead letters. Silicosis was first identified in Portugal in 1938 by two doctors working at the Urgeiriça (Viseu) radium and uranium mine (Brites, 1938; Porto, 1938, 1963). They found that the incidence of the disease among those working in dusty environments was very high: 37 of the 57 drillers and timberers examined had silicosis to some extent. However, in 1942, one year after the creation of the local welfare fund (Caixa de Previdência), the medical report found no evidence of any industrial diseases, then defined as ancylostomiasis and nystagmus, in working miners. Silicosis was often mistaken for bronchitis, which was the most common ailment, with no attempt being made to establish any causal relationship with the workplace (Gançalves, 1961: 2-3). It was not until the 1950s that the medical profession recognized the “white plague”, forcing mining engineers and state managers to recognize it as a major labour issue. In 1960, just as companies were beginning to experience labour shortages, the first symposium on silicosis took place in the Medical Sciences Society in Lisbon.

X-rays became a popular tool for diagnostics, candidate selection and periodic job assignments in Urgeiriça, Aljustrel and other large mines. In the coal mines at Pejão, 50% of mining job applicants failed, leading to mandatory twice-yearly X-ray examinations. Fearing imminent labour shortages, engineers looked for technical solutions to help improve ventilation and health practices among workers (Carneiro, 1956). The disease was related to the mechanization in a few of the country’s larger mines. The first national survey organized by the mining industry took place in 1961 and showed a low incidence rate (3.52%), which was disputed by doctors working in the mines (Andrade, 1961; Gonçalves,1961). Almost 20% of the 2,084 coalminers at Pejão had silicosis. In 1962, it was estimated that at least 10% of industrial workers – 8,000 people – were at risk. Medical experts asked whether or not it was better to remove the worker from the workplace since medical diagnosis by X-ray did not often coincide with the patient’s physical ability and the progress of the disease. Doctors found miners rarely died as a result of silicosis, mainly because it was associated with other life-threatening conditions, such as tuberculosis and cardiovascular diseases, thereby limiting the responsibility of mining firms. Meanwhile, the government promoted national campaigns for industrial accidents and diseases, publishing tables showing official degrees of disability by silicosis, which was recognized as an occupational disease in 1961.

The system of compulsory labour insurance was managed mainly by insurance companies or directly by companies. Both came under financial pressure. Silicosis became a national problem to be solved, just like tuberculosis, cancer and leprosy, through state-sponsored specialist institutes. Compensation was paid following a costly judicial process launched by former workers in courts that were created especially for that purpose. Compensation took the form of a pension that was based on a percentage of wages allocated according to the degree of incapacity. The judgement was based mainly on the X-rays that were controlled by the companies and which often did not reveal the complainant’s actual physical condition. It was not until after 1962 that periodic medical examinations were made compulsory for all companies (Decree 44,308 of 27 April) which were obliged to create medical services for that purpose (Porto, 1963:30). António Fernando Covas Lima (1907-1970), a radiologist and member of the National Assembly, had a key role in promoting mass tuberculosis and silicosis X-ray screening programmes. In 1966, when the Aljustrel anti-tuberculosis centre opened, the law had not yet been implemented everywhere, and the compensation paid out to affected workers was considered low and inappropriate (Lima, 1970).

Insurance companies waived their contracts with mining companies at the number of compensation payments increased. Following the French model, the National Insurance and Occupational Disease Fund (Caixa Nacional de Seguros e Doenças Profissionais) was set up to deal with the ‘national’ silicosis problem (Decree 34,307; Silva, 1962). Mine doctors became a social authority that was linked to this new legal and organizational framework and was a key figure in the emergence of labour medicine and the new professional status ‘situated somewhere between Hippocratic judgements and social facts’ (Saavedra, 1966). For miners, being put out of work exacerbated the miserable condition in which they and their families lived, so while they were aware their condition was in all likelihood fatal, they resisted being laid off (Valisena; Armiero, 2017).

Conclusion: Models of assistance and risk perception

From the end of the 19th century, four models of health and social assistance based in ideological visions of society were apparent in the Portuguese mining industry: private charitable institutions and misericórdias; industrial paternalism; anarchist and syndicalism solidarity; and the fascist welfare system. The first, which existed before the modern mining enterprise, was supported directly by the local elites, the local authorities and the state and was based on the Catholic view of work and the deserving poor that overlapped with the dominant liberal ideology. Misercórdias were unable to meet the demands of industrial operations, and so created space and forced companies to assume the costs of providing their employees and their families with benefits to help them during periods of illness and following industrial accidents. Mutual aid societies developed in the larger mines, where they were first promoted by republicans in competition with the liberal and Catholic vision of assistance. They were designed to offer individuals some dignity and protection against the humiliation of asking for charity and misery of unemployment. This civic idealism also included cooperatives and savings banks operated by independent federalist organizations. However, using patronage and their social power mine managers were able to exercise control over both institutions as they emerged in Aljustrel, São Pedro da Cova and Valongo. However, in São Domingos, mine managers prevented the development of mutual societies while supporting the local cooperative.

Forms of syndicalist and anarchist solidarity first appeared with the emergence of friendly groups or societies (grupos de afinidade) that developed into formal institutions within unions under the Military Dictatorship in the early 1930s, following the publication of legislation allowing unions to create their own welfare schemes.

The fascist welfare system was developed during the 1930s when the state took direct control of the mutual societies and established and supervised company-based welfare funds (caixas de previdência). Compulsory deductions from wages were used to fund cheap pro-natal and childcare policies while reducing the range of benefits managed by bureaucratic organisations. Most importantly: their resources were used to help finance industrial adventures and service state debts. For example, in 1956 34% of the Mason & Barry Welfare Fund’s annual income was used for ‘mathematical reserves’ (see Caixa de Previdência, 1956). This institutional framework was a subsidiary of the state’s economic and labour policies. State guidance developed by setting market prices for minerals and labour that required surveillance of social facts by local police and the institutionalization of ‘social services’ (On the institutionalization of social services, see Martins, 1999). The result was wages that rose below the rate of inflation. In 1942, for example, coal miners at São Pedro da Cova went on strike because they were starving, forced to work under harsh conditions and chased by the police if they ran from the mines (Vieira, 2011). By the 1950s, Mason & Barry was no longer able to afford to dredge the Guadiana to keep it navigable, since market prices affected the price of the superphosphate that was used to fertilize the poor soils of the wheat-producing Alentejo. Workers requesting their pay in advance became the norm, and was denounced in a rhyme that was popular with miners: ‘I never saw so many beggars’.

During this period, the perception of risk in mining work was embedded deeply in power relations and institutional design, as the late emergence of silicosis demonstrates. Most of 1919’s legislation on compulsory health insurances, accident responsibilities and labour relations were either confirmed or reversed in the years that followed. It was at that time that industrial diseases were established as a company responsibility (Decree-Law 5,637 of 10 May 1919). Decree-Law 21,978 of 13 December 1922 established a few of them, leaving aside pneumoconiosis. By the 1950s they had all been identified with tuberculosis, which had become a ‘national disease’ that mobilized state resources. The economic burden of silicosis compensation was postponed until the 1960s and in many ways reduced. The new social authority, the Labour Doctor, was dependent on company policies and compensation was based on a percentage of wages calculated according to a degree of disability that was determined by medical evidence. However, affected workers preferred to be redeployed within the mine than seek to appeal to a hostile or biased court (Silva, 1962).

Nevertheless, this new ‘white plague’ was food for the emerging environmental awareness of mining liabilities. Mine engineers began to consider mines as environments that can be managed to a certain extent with the application of technical solutions, industrial design and scientific labour management in such a manner as to minimize occupational sickness and accidents (Carneiro, 1956). It also affected perceptions of the outcome of a century of mining progress. On the eve of the 1974 Carnation Revolution that overthrew the authoritarian state, and in relation to the development of the Alentejo, one parliamentary deputy said:

Silicosis does not really forgive. The ore is gone, the men are gone, taken by death or affected by emigration, which has depopulated the lower Alentejo. In the south-east, the last census in the municipality of Mértola showed a 44% reduction in its population; in the parish of Corte do Pinto, the former location of a mine, 66% of the population has left – out of every three people in 1960, only one remained in 197010.

New industrial development was badly needed to meet the liabilities of the past.

Sources and bibliography

ACKERS, P. (1998): “On Paternalism: Seven Observations on the Uses and Abuses of the Concept in Industrial Relations, Past and Present”. Historical Studies in Industrial Relations, 5: 173–93.

ALARCÃO, Alberto (1971): [Intervenção], Diário da Assembleia Nacional, X Legislatura, S. 117, July 2nd.

ALVES, H. (1997): Mina de São Domingos. Génese, Formação Social e Identidade Mineira, Mértola, Campo Arqueológico.

ALMEIDA, A. S. (2017): A saúde no Estado Novo de Salazar (1933-1968): políticas, sistemas e estruturas, Ph.D. Thesis, Lisbon, UL.

ANDRADE, A. C. (1961): “Inquérito preliminar sobre a silicose em minas por radiofotografia”, Boletim de Minas 9, Lisbon.

ALJUSTREL. Arquivo Histórico. Administração do Concelho (1902): Copy of correspondence issued to the Beja Civil Government, letter no. 344 (Sept.).

ASSOCIAÇÃO de Auxílio aos Pobres (Mina de São Domingos). Cozinha Económica (1942-1943): Livro de registo mensal de devedores, Sindicato dos Trabalhadores da Indústria Mineira (Arquivo), Aljustrel.

ASSOCIAÇÃO de Socorros Mútuos «Mineira Aljustrelense» (1907): Estatutos, Almodôvar.

ASSOCIAÇÃO de Socorros Mútuos «Mineira Aljustrelense» (1909, 1910): Relatório e Contas da Gerência, Lisboa de 1910, 1911.

BENTO, M. C. (2013): Vida e morte numa mina do Alentejo: pobreza, mutualismo e provisão social: o caso de S. Domingos, Mértola, na primeira metade do séc. XX, Castro Verde, 100Luz.

BERTAUX, D. (1977): Destins personnels et structure de classe. Paris: P.U.F.

BLUMA, L. & RAINHORN, J. (2015): A History of the Workplace: Environment and Health at Stake, Routledge.

BRITES, G. (1938): “O nódulo pneumoconiótico dos mineiros da Urgeiriça”, Coimbra Médica, 8 (Oct.).

CAIXA DE PREVIDÊNCIA da Firma Mason & Barry (1956-1974): Relatórios e Contas da Direcção (Arch. Sindicato dos Trabalhadores da Indústria Mineira).

CAIXA de Solidariedade aos Doentes Pobres (1933-1940): Relatórios e Contas da Direcção. Associação de Classe dos Operários Mineiros de Aljustrel. (Arq. Hist. Aljustrel).

CARNEIRO, F. S. (1956): “Aspectos gerais da silicose”, Estudos, notas e trabalhos do Serviço de Fomento Mineiro 1, Porto.

CASTRO, F. (1986): “História da Velha Mina” [1932], Diário do Alentejo, March 14 th, supl. cultural O Largo, 22.

CUSTÓDIO, J. (2013): Minas de S. Domingos: território, história e património mineiro, Lisboa, ISEG.

ENCICLOPÉDIA, Editorial (1957): “Mutualismo”, Grande Enciclopédia Portuguesa e Brasileira, M:311–15, Lisboa; Rio de Janeiro.

FERREIRA, C. (2012): “Impactes ambientais de explorações mineiras desactivadas. O caso das minas de S. Pedro da Cova – Gondomar”, Grandes Problemáticas do Espaço Europeu, Porto, FLUP: 148 – 162.

FIDALGO, A. V. (2018): Património Social da Mina do Lousal: Do Hospital à Exposição, Master Thesis, Lisbon, FCSH/UNL.

FONSECA, I. (2005): Trabalho, identidade e memórias em Aljustrel: “levávamos a foice logo p’ra mina”, Ph.D. Thesis, U.N.L.

GARRIDO, Á. et. al. (2017): Cem Anos de Políticas Sociais e do Trabalho, Cadernos Sociedade e Trabalho, 20, Lisboa, MTSSS.

GONÇALVES, A. R. (2012): “Riscos associados à exploração mineira: o caso das minas da Panasqueira”, Cadernos de Geografia, 30-3.

GONÇALVES, A. R. (2015): Alterações ambientais e riscos associados à exploração mineira no médio curso do rio Zêzere: o caso das minas da Panasqueira. Ph.D. Thesis, Coimbra, 2015.

GONÇALVES, S. A. (1961): “Alguns aspectos médico-sociais do problema da silicose”, O Médico, 533.

GOODOLPHIM, C. (1876): A Associação : Historia e Desenvolvimento das Associações Portuguesas, Lisbon, Tip. Universal.

GRILO, J. Francisco (1924): “Inquérito às Condições de Vida Económica do Operariado Português”, Boletim da Previdência Social, 14, Julho-Dezembro 1923, Lisboa, Imprensa Nacional, 1924.

GRILO, J. Francisco (1926): “A Assistência Pública em Portugal”, Boletim da Previdência Social, Lisbon.

GUIMARÃES, Paulo E. (1989): Indústria, Mineiros e Sindicatos: universos operários do Baixo Alentejo dos finais do século XIX à primeira metade do século XX, Lisboa: Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade de Lisboa.

GUIMARÃES, Paulo E. (2001): Indústria e conflito no meio rural: os mineiros alentejanos (1858-1938), Lisboa, Cidehus.

GUIMARÃES, Paulo E. (2002): “Comunidad, clase y cultura en los trabajadores mineros del Sur de Portugal”, Política y Sociedad, 39 (2): 457-479.

HARRIS, B. & BRIDGEN, P. (2007): Charity and Mutual Aid in Europe and North America since 1800, Routledge.

JAQUES, F. P. (1947): Alguns Aspectos Sociais da Região Mineira de São Domingos: Monografia, Lisboa, Instituto Superior de Serviço Social.

VAN LEEUWEN, M. H. D. (1997): “Trade unions and the provision of welfare in the Netherlands, 1910-1960”, Economic History Review, L, 4: 764-791.

VAN LEEUWEN, M. H. D. (2007): “Historical Welfare Economics in the Nineteenth Century: Mutual Aid and Private Insurance for Burial, Sickness, Old Age, Widowhood, and Unemployment in the Netherlands”. In Charity and mutual aid in Europe and North America since 1800, New York, Routledge: 89-130

LIMA, J. C. (1970): [Intervenção], Diário da Assembleia nacional, X leg., s. 46, April 30th.

MARTINS, A. M. C. (1999): Génese, emergência e institucionalização do serviço social português, Lisboa, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian.

MISERICÓRDIA de Aljustrel (1913): Estatutos da Misericórdia e do Hospital Civil da Vila de Aljustrel, Beja, Minerva Comercial.

MONTENEGRO, A. (1903): Inquérito de Salubridade das Povoações mais Importantes de Portugal, Lisbon.

MONTEPIO Aljustrelense (1904): Estatutos do Montepio Aljustrelense [1894], Évora, Minerva Comercial.

MOURÃO, G. M. (1911): [Sobre o Montepio Mineiro]. A Revolta, 1, 11, Aljustrel, April 13.

NASH, L. (2014): “Beyond Virgin Soils: Disease as Environmental History”. In Isenberg, A. C. (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Environmental History, Oxford y Nueva York: Oxford University Press: 76-107

PEREIRA, M. H. (2010): “As origens do Estado-Providência: as novas fronteiras entre público e privado”, O Gosto pela História: Percursos de História Contemporânea, Lisboa, ICS:165-201.

PÉREZ-CEBADA, Juan Diego (2020): “El derecho del trabajador al aire puro: contaminación atmosférica, salud y empresas en las cuencas de minerales no ferrosos (1800-1945)”. Historia Crítica, 76: 27-43

NUNES, J. P. (2005): O Estado Novo e o volfrâmio (1933-1947): projectos de sociedade e opções geoestratégicas em contextos de recessão e de guerra económica, Coimbra.

PATRIARCA, F. (1995): A questão social no salazarismo (1930-1947), 2 vols., Lisboa, Universidade de Lisboa.

PIMENTEL, I. (2016): “A assistência social e a previdência corporativa no Estado Novo”, Intervenção Social, 47 (8).

PORTO, J. (1938): “A silicose pulmonar nos mineiros da Urgeiriça”, Coimbra Médica, 5 (Feb.).

PORTO, J. (1963): Alguns aspectos médico-sociais da silicose. Figueira da Foz.

REID, D. (1985): “Industrial Paternalism: Discourse and Practice in Nineteenth-Century French Mining and Metallurgy”, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 27 (4): 579–607.

ROCHA, I. V. (1997): O carvão numa economia nacional: o caso das minas do Pejão, Porto.

ROCHA, N. (2010): Couto mineiro do Espadanal (Rio Maior). História, património, identidade. M. Thesis, Heritage Studies, Lisbon.

RODRIGUES, P. (2005): Vidas na mina: memórias, percursos e identidades, Oeiras, Celta.

RODRIGUES, P. (2013): Onde o Sol não Chega: vidas, trabalho e família na mina do Lousal, Alcochete, Alfarroba.

ROSENDO, Vasco (1996): O mutualismo em Portugal: dois séculos de história e suas origens, [Lisboa], Montepio Geral.

SAAVEDRA, António (1966): “O Médico do Trabalho e a Silicose”, Estudos Sociais e Corporativos, ano IV, Lisbon.

SELLERS, C. C. (1997): Hazards of the Job: From Industrial Disease to Environmental Health Science, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press.

SILVA, Nuno D. (1962): “Bases médico-legais da indemnização da silicose”, Boletim Clínico dos Hospitais Civis de Lisboa, 26 (1/2).

SINDICATO dos Operários da Indústria Mineira de S. Domingos (1938-1974): Relatórios e contas.

SINDICATO dos Operários da Indústria Mineira de S. Domingos (1931): Rumores subterrâneos, 1931. (BNP. Arquivo Histórico-Social).

SINDICATO Nacional dos Trabalhadores da Indústria Mineira e Ofícios Correlativos do Distrito de Beja (Mina de São Domingos). Cozinha Económica, (1941-1943): Diário no 2. Sindicato dos Trabalhadores da Indústria Mineira (Arquivo).

VALISENA, D. y ARMIERO, M. (2017): “Coal lives : body, work and memory among Italian miners in Wallonia, Belgium”, in M. Armiero and Richard P. Tucker (eds.), Environmental History of Modern Migrations, London, Routledge: 88–107.

VEIGA, C. (2014): A vida dos trabalhadores do urânio “trabalho ruim”, [Nelas], Associação dos Ex-Trabalhadores das Minas de Urânio.

VIEIRA, D. F. O. (2011): “Não podiam trabalhar com fome”: A Greve de 1946 nas Minas de São Pedro da Cova. M. Thesis, Porto.

WHITESIDE, N. (1996), “Creating the Welfare State in Britain, 1945–1960”, Journal of Social Policy, 25 (1): 83-103.

1 This study was conducted at the Research Center in Political Science (UID/CPO/0758/2019), University of Évora, and was supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology and the Portuguese Ministry of Education and Science through national funds. It was presented at the Third Conference of the European Labor History Network Conference, Amsterdam, 18-21 September 2019 (Network: Labor in Mining).

2 The villages at the São Domingos mine: Corte Pinto, Santana de Cambas and Pomarão, near the river Guadiana.

3 Mine workers were divided into three classes. We have considered the most common wage paid to those in the third class.

4 “O movimento dos associados durante o ano não correspondeu aos nossos desejos. Baldados foram todos os esforços para novas admissões, que deveriam registar-se se entre o operariado mineiro houvesse a necessária compreensão dos deveres que lhe incumbe de procurar na associação o próprio amparo e de suas famílias em caso de doença. Até mesmo as instâncias e conselhos aos operários foram infrutíferos, parecendo acolherem com quase antipatia e desconfiança a renovação de pedidos para se inscreverem. Como se o progresso da associação não revertesse em seu próprio beneficio” (Associação de Socorros Mútuos «Mineira Aljustrelense», «Relatório e Contas da Gerência, 1909». p.4).

5 1,000 reis = 1 escudo; 1,000 escudos = 1 conto. In 1913, a miner from Aljustrel earned 600 reis. In 1938, a miner’s average daily wage was 10-12 escudos (Boletim de Minas).

6 Ministério do Trabalho Archive (ISSOPS), Box 4, file 250, letters dated 9 December 1929 and 26 February 1930 to the Sindicato dos Operários da Indústria Mineira de São Domingos, and the reply dated 20 April 1930. The general compulsory accident insurance fund established by law in 1919 had been suspended since the creation of the fund required the British company’s prior approval.

7 “O povo não tem confiança no médico, motivo porque só depois de aplicar toda a medicina caseira, mezinhas e benzeduras, recorre à ciência. Alega que o médico não escuta os doentes, bastando-lhe olhar o doente para passar receita. O problema da assistência médica é o que mais revolta a população”.

8 Associação de Auxílio aos Pobres (Mina de São Domingos), «Cozinha Económica / (Livro de registo mensal de devedores).»; PORTUGAL. Sindicato dos Trabalhadores da Indústria Mineira (Arquivo), «Cozinha Económica / Diário no 2.».

9 Law 1,942 (DG 174 of 27 July 1936) considered occupational diseases as those caused by poisoning by industrial dust, gases and vapor. The 1937 law on accidents at work was wordy and established bureaucratic procedures and left responsibility to be determined by the Workplace Accident Courts, which were usually ineffective and hostile to workers.